Comics are art. That’s a no-brainer. And not just because Fantagraphics “told you so,” at great length and with many detours. In its fundamental root meaning, “art” is any skill or craft. But the definition sharpens and becomes refined once you start adding prefixes. Visual art. Decorative art. Applied art. Narrative art. Performance art. Comics can easily be squeezed into a couple of those categories. But once you ignite that value-judgment-charged word “fine,” things start to explode all over the place.

The original premise of the following discussion, conducted in 2012, was to examine where comics are situated in the cultural continuum. As to why this is important in the first place, the most obvious answer has to do with the comics community’s desire to rise above being the Rodney Dangerfield of the arts.

Fortunately, our discourse spread far and wide beyond that particular issue. Indeed, it often took a back seat to other, more substantive concerns and experiences. And since Marc Bell, Esther Pearl Watson, Joe Coleman, and Robert Williams — each in his or her own way a master of the fine art of conversation, as you can read in their solo follow-up interviews, which will be published over the following weeks— were driving the discussion, you can just kick back and enjoy the ride.

— Michael Dooley

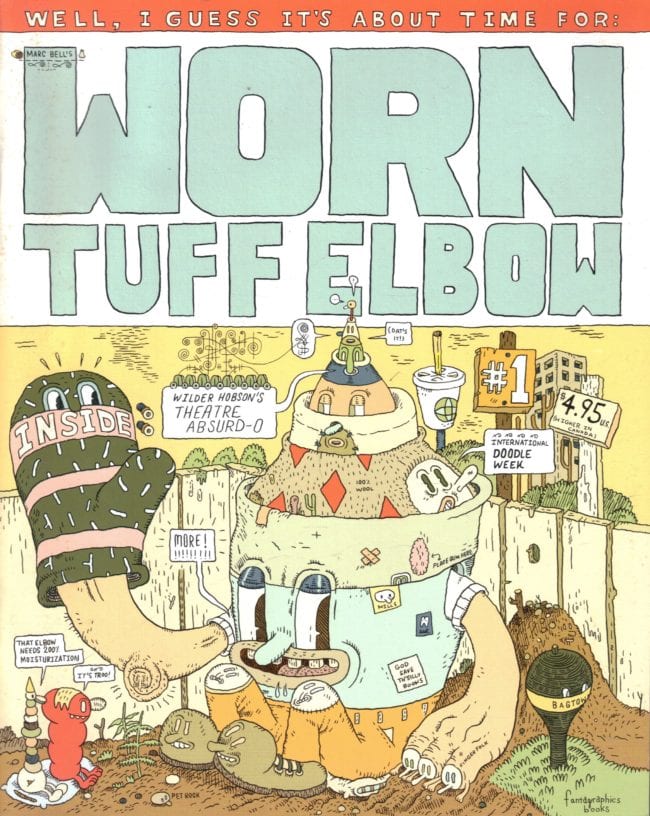

MICHAEL DOOLEY: I’ll be the ringleader, ringmaster. In the first e-mail that I got from Michael Dean, he said, “We’re thinking about putting together a conversation between a group of artists who straddle the border between fine art and cartooning, and we need a moderator.” So that’s me. Gary Groth volunteered me. So since it’s the border between fine art and cartooning, probably the best thing to do to make sure we’re all talking about the same thing is go around and ask everybody what they see as the definition of fine art, starting with Marc, then go to Esther, and Joe, and Robert. So Marc I have a quote here you once said: “David Cooper said to me, ‘Think of yourself as an artist who happens to do comics.’” So do you see yourself as a fine artist?

MARC BELL: Well, I guess I would sort of see myself as a fine artist when I’m showing work in galleries. I would say fine art is about the object, and then cartooning is about printed material or being in a book. I couldn’t say what is fine art and what is not, but fine art seems to be more about the object and person, whereas comics and graphics and things like that are more about being a book … you follow me? That’s a very general statement, but …

DOOLEY: Yeah, so I was wondering if that would exclude like serigraphs and silkscreens and things like that that go through the printing process?

BELL: When you’re going to a gallery you’re looking at a thing as an object, even if it had been printed in a book. Or if you’re looking at comic originals and you’re looking at them in a gallery, you’re looking at them as an object, whereas cartooning, its end result is to be in a book essentially. And if you’re looking at a, say comics page in a gallery, then it’s kind of like an artifact or something.

DOOLEY: So then for you it’s the object in a gallery, so the setting as well plays a factor.

BELL: I think so. I mean with art you kind of want to see it in person, I think. It’s a personal judgment, what someone thinks is fine art or not.

DOOLEY: OK, and that’s how you distinguish between your fine art career and your comics career?

BELL: Yeah, I mean when I’m doing comics I’m trying to think, OK, how would a person read this? And there’s certain crossover of course, but when I’m making art I’ll be thinking, would this look good or could this be put in a book, or how would this be presented in a book? And then when I’m making art I’m sort of trying to make things … when I’m doing something for a gallery, I’m trying to make something that would look good on the wall. For example, I’ve seen Joe’s stuff in reproduction and it looked interesting to me, but you know, to see it in person, that’s where it really kind of knocked me out when I saw a big show with a bunch of his stuff.

DOOLEY: OK. All right, now Esther … I got one quote from you, it says “I’ve been called lots of things. Faux-naïve, faux-grotesque, insider-outsider.” So what do you call yourself?

ESTHER PEARL WATSON: Well, lately I’ve kind of just given up trying to separate the comics from the paintings and I realized that I’m basically investigating the same thing. I’m very interested in the language of storytelling and narrative, and I’m fascinated by the whole lexicon of comics and disrupting that and disrupting narrative even in my paintings. So I feel like they are a lot more similar than ever before if that makes sense.

DOOLEY: OK, so your paintings you would consider fine art?

WATSON: And my comics as well, actually. I do understand what Marc is talking about as well with the difference between the work being printed as opposed to seeing it in person. You have a completely different experience, but for me, both the printed work and the work you experience in person are still under the same investigation. I would call them both fine art.

DOOLEY: OK, and would you have like a summary definition then of fine art?

WATSON: For me, fine art is making an investigation. It’d be asking a question, whether it’s theoretical or philosophical, and not necessarily answering it, but asking a question.

DOOLEY: Now Joe, you one time said, “I don’t know about art, I don’t know what the word means.” So give it a shot anyway. [laughs]. What’s your take on the words “fine art”?

JOE COLEMAN: It’s an interesting topic of course, and a lot of people have struggled with this for years. I mean, for a long time, photography was not considered an art form, nor was film. And I think it was Jean Dubuffet who once said that when art’s name is called, it runs and hides [Someone laughs]. But maybe what he really meant was, when art’s name’s called, I grab my shotgun. But I guess that’s what I thought about back when I was doing performances in the old days. But I don’t have the answers.

Also, a strange thing happened when I did a solo show in a museum in Berlin. Along with my paintings, they framed the colors that I did for Screw magazine and illustrations … they just took the pages out, not the originals, just the pages, and hung them in this museum in Berlin. And they had the illustrations I had done for Hustler, but not the actual paintings. They had original works of art as well, but I thought it interesting they would hang these things as part of the whole package. And I work with some of the sleaziest publishers around, aside from Al Goldstein and Myron Fass. And I was happy with those days of doing comics and illustration, but I think what’s different is, when you’re working for somebody else, and somebody else is paying your paycheck, and you’re given an assignment, I think that’s what makes it illustration. I think in the realm of comics, the people that write their stuff and draw their own stuff, and put it out there, I think that’s a valid art form, and that’s a true art form. Because I don’t think that that’s necessarily illustration.

DOOLEY: Do you distinguish between, say, what you do as illustration or fine art?

COLEMAN: Well yeah, what I do is not illustration. It’s in a tradition … I mean it’s already been accepted as fine art because I show with the Dickinson Gallery and one of my paintings was sold at Christie’s with other already accepted works of art, so it’s already not illustration.

DOOLEY: And your covers for Screw and such, since that’s printed material, do you not consider that part of the art? Are you kind of in agreement with Marc on that?

COLEMAN: Well to me the fact that they were hung in this museum, that almost qualifies it as art. But even though when I was making it, I didn’t care as much about a cover that I was doing for Screw magazine as a painting I was doing … or even when I was doing my comics for myself. When I was doing The Mystery of Wolverine Woo-bait, which was a comic, I owned all of that. Which is different from an assignment that somebody gives you. So I think that there’s a definition there in which illustration is qualified by a job. I self-produced my comic book The Mystery of Wolverine Woo-bait and I think that that’s different.

DOOLEY: Yeah. So having been assigned to do an illustration and having gotten paid by Goldstein then that would be an aspect of illustration?

COLEMAN: Yeah! That would be illustration.

DOOLEY: OK. Now let’s hear from Robert. [Chuckles.] I think you have one or two thoughts about what constitutes fine arts. So share them with us.

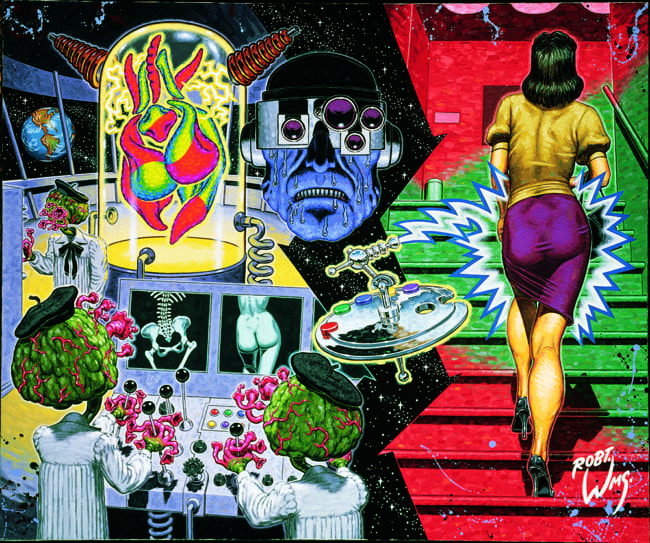

ROBERT WILLIAMS: Well, it’s kinda hard to follow Joe there, he’s a hard act to follow. Supposedly art is culturally the highest pinnacle of expression. And the word fine makes a big difference and that’s the big phony bone of contention. That word “fine” is supposed to imply sophistication. So sophisticated art. And this is a word that’s been around for a long, long time culturally and it’s a big selling point over a couple hundred years now. Just stick that word “fine” on it. It’s dribbled through our Western culture for a long time and you watch these revolutionary art movements come out of the late nineteenth century and then the period of the first world war. Then somehow they got to the top. The thing is, art is not just run by a few people. It’s run by schools and institutions and foundations and museums and art dealers. And the artists play a small part in that art thing and it’s unfortunate. You see artists get really famous and you wonder, “Well how’d that guy get so famous? That thing looks kinda goofy to me.” And it’s just that he was selected by this group, that this is gonna be what they were gonna push. Every new revolutionary form of art tries to violate that established situation. You can see that. You look at Van Gogh and you understand that if Van Gogh was born in the 20th century, he would have been an underground cartoonist. There’s no question about that. You look at that stuff and it’s calligraphy-dependent, it’s dependent on the drawn line. I know underground cartoonists that were comparable to that. So the question of “fine,” you know everyone wants to just tack that on them. People building model airplanes wanna tack that on. The thing is when nouveau riche people come into the buying market, dealers jump on these ignorant people and guide them. So they guide them to what’s pretty much easily established. So since the end of World War II, abstract expressionism kind of took over. Europe was really down on its luck and New York became the world’s art capital. It was a couple of New York art critics that pushed Jackson Pollock and he was in Life magazine and just busted this thing wide open. So nonobjective art just completely took over. And for nonobjective art to really get a good handle, these two art critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, instigators in this, kind of inferred that, if you visually depended, mentally depended on three-dimensional representation, you were kind of ignorant and you just didn’t have the sensitivity to appreciate two-dimensional and nonobjective art.

So that’s been kind of the mantra here in the last 50 years. It’s gone from abstract expressionism into pop art and to conceptualism. And you think, “Well wait a minute. You said pop art. That’s realistic stuff.” Well yeah, but it’s total appropriation. That’s like going to the 99¢ store and going up to the first shelf and grabbing something off the shelf and taking it over to one of these places that makes art for artists and say, “Can you make this about 20 feet tall for me?”

In the 50 years that’s passed, really talented and imaginative artists have been kind of set off to the side, and they’ve had to find their forms of expression in commercial art and taking commissions if they got involved in magazine illustration, B-movie posters, and things like that, you know. So when I was a young man I was interested in art, and I realized I had a certain facile ability to draw. I thought, well, you know I’m going to go to art school and man, I’m going to be a whiz. But I didn’t realize that I was coming into the art world right in the middle of abstract expressionism and then really talented people went into comic books and other forms of art, working for the movie studios and whatnot. And I was kind of shit out of luck when I got into art school. I could just as soon have done better if I’d tied a brick around my hand.

But the thing is, realism had a reason to die too because it got so saccharin and so crappy and so reminiscent of the past and nostalgic and Norman Rockwell-ish that it was killing itself. So I came out to California. I got an art education, in spite of not being in vogue, and I was always referred to by my art peers as “the illustrator.” I lack the mental sensitivity and expanded horizons to understand two-dimensional art. So I was always working at a real deficit there. When I was young I got into comic books because they were really a wonderful way to exercise your eyes and your mind, and I loved drawings. As I began to read at 7 or 8 years old, I got into EC comic books, and then, when Mad came out, I got into Mad, and I developed a real understanding of abstract humor in comic books. And I loved drawing, I just loved to follow those EC artists. The fine artist I liked was Salvador Dalí and maybe a handful of others, but I really liked the exercise of imagination. I just was born at the wrong time. So I had the idea of painting naked ladies and hot rods and chrome and adventure and daring and man, I was way off on the wrong track. I was just much happier in the comic books. So when I had a chance to get into Zap Comix, I realized that I could just pull out all the stops. It was just a wide-open highway, as I could just go as far out as I was allowed to go.

Now the interesting thing about the very first underground comic books was: They were very close to fine art because they didn’t depend on a giant buying market. They were for a small, arcane bunch of characters that were bohemians, that did drugs, that had some semblance of intellectuality. And I really love that, because I can slip off into goofy abstraction. But as the underground comics got bigger and bigger, a more literary demand started developing, and the bigger the audience got, the less they were interested in odd forms of abstraction, and they wanted stories portrayed and whatnot. I’d always been a painter, and I’d been lucky enough to sell my paintings but never get gallery shows because it just didn’t fit in, it just would not fit in. But I kept painting and the comics really helped my painting. One thing a comic book has is a sense of a fourth dimension of time. It’s art with time. In other words, the movie industry is your most premiere form of art, because it’s got time and motion and literature and everything involved in it. But your second best form of art is a comic book because it’s a graphic novel. But there’s a problem with the comic book, and that is: Every panel in a comic book is a lead-in to the next panel. It’s expendable; it’s just there for the next panel. So you lack the drama of that one panel, and painting had that drama, and I was still hooked on painting. But I learned that since striving for that fourth and even fifth dimension, the fourth dimension being time and the fifth dimension being the violation of physics, which happens in surrealism and whatnot. So that’s about my story right there, to answer your question about my interpretation of fine art.

DOOLEY: I do want to hear from the others about their evolution, as it were. But first, Robert, just to clarify: I know you were saying two things about fine art. Number one is that you didn’t particularly care for the term “fine,” and the other was that underground comics, in your opinion, came close to fine art in that they didn’t depend on a giant buying market. So is that for you part of what fine art is, it’s, like underground comics, kind of an exclusive club?

WILLIAMS: Well, that’s exactly right, because if I want to deal with the general public, I do Disney-esque, big-eyed children, things like that that are more acceptable to a large, sensitive audience. I like a select audience that likes to investigate things. I don’t want to do things that are laid out real simple. I like to do what interests me in my form of expression and sometimes that hurts a lot of people. I’ve stepped on a lot of toes.

DOOLEY: [Laughs.] So then your definition somewhat aligns to what Joe was saying. In terms of not doing it as an assignment for a paycheck.

WILLIAMS: No, it’s not a commission. I haven’t taken a commission since 1970.

DOOLEY: Let’s go back to Marc. How would you see your evolution?

BELL: Well, I started out drawing comics influenced by ’70s Mad magazine and then I moved on and started reading Chester Brown and Peter Bagge, Julie Doucet and stuff like that. And then I started publishing. So I was big into comics. I went to art school and I was also doing art at the same time, but when I left school, comics just seemed to be a good way to get my work out there, because you can print in multiples and you can mail them around. I was collaborating with friends, making drawing books, and those are good because you don’t have to have a gallery, you can just put these drawings in a book and send them around. I was kind of doing both, really. And then comics started to drive me a little crazy, just making them. And I started getting more interested in just making straight-up artwork where I didn’t have to tell a story or try to tell a story. So I kind of moved more into art at that point. I mean, I’m not sure … that’s a pretty brief little history.

DOOLEY: There was that interview where you were talking about how the narrative aspect of it didn’t interest you. You were dissatisfied with your writing. That was more your transition from comics to fine art?

BELL: Yeah, I mean I was always doing art stuff and making comic art at the same time, but then I just decided to switch over into art and abandon trying to make narratives. I mean in my artwork I’m still using tons of text and people still call me a cartoonist, like I’ll never be able to escape. And I don’t want to necessarily, but I’m still a cartoonist in whatever little part of the so-called fine-art world. I’m still a cartoonist essentially because I guess that’s how I came up, how I became known.

DOOLEY: And Esther, I know you go back to being an Art Center student. What’s your career path?

WATSON: Well, I started off as an illustrator and got into comics through an art director at Entertainment Weekly who gave us a pirated copy of a Ron Regé Jr. minicomic. And I really liked that she helped keep this small-press publication in print by pirating it herself and passing it along. My husband, Mark Todd, and I both thought that was a wonderful rebellion to the publishing industry we were in and pursuing, but also a way to get people to hold on to our material and not throw it away, because we were used to sending out hundreds and thousands of samples of our work and just seeing a lot of art directors throw it in the trash. And we would see art directors hold on to the comics and for the longest time I kind of thought that was Mark’s thing because he grew up reading comics. So making a minicomic was kind of his thing. Until I came out to California, and Mark and I had found this diary, this teenage girl’s diary, and I had tried to publish it in so many different ways, and finally I just gave up trying to publish it through the major publishing system, and I did everything I was not allowed to do. And I actually on purpose just took all the rejects and made that book. It was rejected for: You can’t make fun of the main character, nobody cares about a real diary, nobody cares about the ’80s, and so I decided to just draw all of that on purpose and publish it myself and it was very cathartic to be able to just do everything wrong and it just cracked me up, it just made me laugh. It was so freeing.

So that’s kind of how I got into minicomics. We started selling our comics at Comic-Con and at Alternative Press Expo and getting a lot of response. We were keeping our comics separate from the illustration world and fine-art world and for a while, I was even thinking, “Oh, I have to have a separate website for everything. But now I am starting to really embrace the idea that everything I do is my art. There’s no reason to separate commercial work or the gallery work or the comics anymore. I feel like now I’ve gotten to a point where I only accept commercial work if it sounds fun to do. I just did a piece for The New York Times and it was a lot of fun. I got great response and sold a ton of paintings because of it. And then I can make my comics. I feel like everything I do now goes back to the central message I’m trying to make. So as long as I’m having fun [laughs], I’m cool with whatever name anybody wants to call my work. But I think it’s all the same thing.

DOOLEY: And your central message has to do with asking questions, right?

WATSON: Yeah, I’m really interested in storytelling. I’m really interested in the idea of the outsider, and what is that really? I feel like we all consider ourselves outsiders in some shape or form. It’s basically what it is to be a human being on this planet.

DOOLEY: And Joe, you’ve been painting since you were about 4 or 5 years old?

COLEMAN: Yeah.

DOOLEY: So, want to give us a rundown on how that developed?

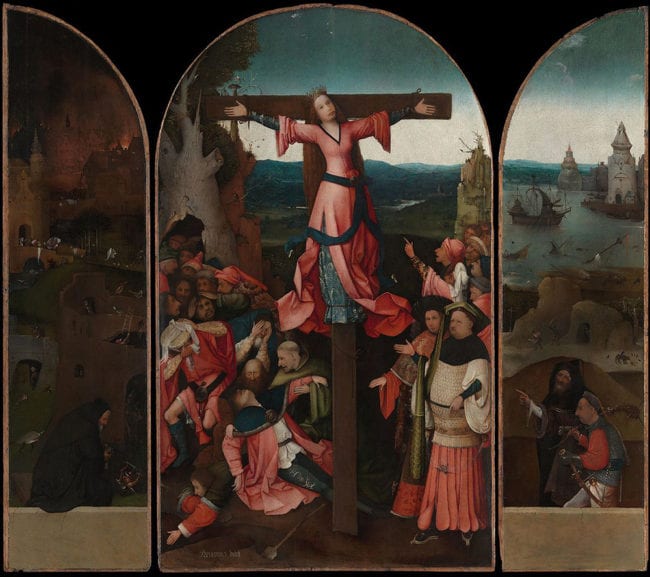

COLEMAN: Well, even before I saw comic books, I was raised Irish Catholic. I always like to say “Irish,” because I think the pagan slant to Catholicism puts a little English on the disturbance that I call Catholicism. [Dooley laughs.] So my mom, she was amazing. She loved art and drama and she gave me this pad with a pencil and a crayon while I was in church, just to occupy my mind. And I thought it was wonderful. I was looking at the stations of the cross that were in relief going toward the altar, and at the altar is this guy being crucified, nailed to a cross. And I thought that’s pretty fucking cool. So then I started drawing it. And I used a pencil to draw all the stations of the cross. I would copy these relief images of Christ being whipped and crowned with thorns and having the Roman soldiers play dice for his robes. And then crucified and then his body taken away. And then the only crayon that I used was the red crayon for the blood. And it was storytelling. It was sequential art. I was fascinated by that from a very innocent time, and then because of problems that I had in school, I was put on the short bus and I was put in this class where they taught me art therapy. It was kind of a fun thing because I got to get out of a lot of classes because I hated school. And if somebody’s just going to put me in a class where I just draw all day, it was great. And then I started to see comic books. I think it was probably around the same time because my mom bought me a book on Hieronymus Bosch — I still have it, it’s a really small book — because she saw my drawings and she found a connection there. And I loved this book on Hieronymus Bosch. I was obsessed with him and I still am. But then I looked at … I wasn’t really interested in superhero comics, but then I saw Creepy magazine, the first couple issues, and I thought that it was amazing. It really excited my imagination and there was something that I loved about just drawing and the draftsmanship of these artists. And it did harken back to what I saw with religious art, you know.

When I was much older, I got fascinated with illuminated manuscripts, and how they are the kind of narrative that I want to tell. Because I like the fact that you can have images and text all at the same time. But unlike in my work, unlike in a movie or a comic book. Because I haven’t done a comic book in many, many years, but I still feel a connection to comic books, because what I’m doing now is a narrative art that has text and images. It’s so dense with text and images that you have to choose where you’re gonna go. So for each person that looks at one of my paintings, the process of entering the work is going to be different. One person might look at the left side of the painting and another person looks at the right side of the painting. And each person has a different experience. And the more that you read and the more that you look, the more that you experience. I’ve had collectors that have had a painting of mine for some five years, and one day I’ll get a call out of nowhere, and some collector says, “Joe, I found this thing that I hadn’t seen … you know, I’ve been looking at this painting for years and now I understand the connection between the different elements that are going on on the surface of this painting.” Every detail that I put into a painting is not extraneous. It’s very specific to the story I’m trying to tell. Every minute detail is very specific. Whether it’s like a flower or a number on a door, it is part of the whole narrative structure. For some reason they categorize me as an outsider. I know Esther was talking about that a minute ago, but as far as I’m concerned, I really hate the term outsider. But the fact that someone would show my work and put it in this magazine Raw Vision, I love those people. They’re very interested in art. And I also hate the idea of lowbrow art. I mean I can’t stand these labels. I think we have to get rid of these labels, you know —

WATSON: I agree.

COLEMAN: I mean there’s good art and there’s bad art, and you don’t need to label beyond that. And also your personal taste on what you like and what you don’t like. I mean, I’m happy that I’ve met some really great people that were behind the outsider-art world or the lowbrow-art world, but it’s not really so important as the work. The only thing that’s really important to me is to do the work.

DOOLEY: Are there any advantages to being called an outsider artist? Or is it just all downside?

COLEMAN: I think it’s a bunch of bullshit — not for me, but for people that are being exploited by that term. Because if they come up with this way of selling art, in which the person who’s producing the art is somehow either psychologically or physically deformed and can’t take care of themselves, and the gallery is controlling those works, they get nothing. It’s the worst exploitation of an art form. And I think, actually, it’s kind of dangerous to sell a work strictly on the suffering of the artist. They’re selling stuff because a guy had shock treatments, or he is a junkie, or whatever the fuck they’re coming up with. But I think what you should do is look at the art first. Then you look at the history. You know you don’t sell it by the trauma. I mean that’s a really bad and dangerous way to go. I mean, look at what Van Gogh went through, or you look at any human being. To start a whole art form based on the short bus, that I’ve already experienced, I don’t think that’s a good way to sell art. I think it’s a dangerous way to sell art.

DOOLEY: Could you give a specific example, say, of how this label has led to a disadvantage for you?

COLEMAN: Well it hasn’t led to a real disadvantage to me, but there was the outsider art fair in New York City, and a lot of those people were my friends. But there was a certain director there that didn’t want me to come around anymore. And so I got kicked out of the outsiders. So maybe it’s a new form of outsider art. Outside the outside. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: Have you had bad experiences with labels that have held your career back?

COLEMAN: Well, I mean, I don’t know if you know my performance art stuff, but I performed in mainstream performance spaces like The Kitchen and Boston Film and Video Arts Foundation. And I was getting arrested for these performances, and now they’re legendary. At the time maybe it’s what I needed to do. And what’s kind of wonderfully strange, and I never expected it, is that the things that I did that my family said were wrong and everybody hated me for, have now somehow blossomed into favorable things, legendary things. Now I don’t regard it as part of the essence of what I do. I don’t know how that happened. I would never be able to predict it, it just happened. It’s not a formula you can teach in school. I would be a terrible teacher, because I would tell everyone, “Get the fuck out of here.” [Laughter.] “Go out, live. Then you’ll find out what to paint, or what to form, or what to blow up. Or what to shoot at. You’re on your own. You’re not going to find it in a school, absolutely not.”

BELL: Does anybody know those Gee’s Bend quilts?

WATSON: Oh yes, uh-huh.

BELL: They’re pretty beautiful, and I think those are maybe a good example of some good coming out of exposing folk art that might have been lost, or whatever term you want to use, art being lost. I mean those are pretty amazing things. I just read that book by Bill Arnett, [The Last] Folk Hero; he’s kind of a controversial figure, but he seemed to do a lot of good for that community. I’m just trying to bring up maybe a positive side to —

COLEMAN: I think the fact that these works are finally being seen, and that they have some champion behind them, is really important, and I love that. But I think that the works of [Adolf] Wölfli and [Henry] Darger and some really special people that are called “outsiders” should be considered fine art, and should be considered in the same breath. And they are worthy of it, and they should not be relegated to some dismissive, apologetic part of art. I’m against that.

BELL: Yeah I mean, because you look at these Gee’s Bend quilts and they look better than that kind of minimalist painting that was going on in New York probably at the time. They’re pretty beautiful.

COLEMAN: Absolutely. And it should be treated with the respect that it’s due.

WATSON: Yeah, exactly.

WILLIAMS: So, this would be like a folk art that …

COLEMAN: No, forget about folk art! Folk art has to be destroyed. The whole idea of folk art is a total manipulation by galleries and it’s a bunch of bullshit. No, there’s good art and there’s bad art. And if it speaks to you in some way … I like things that talk from the gut and from the heart. A lot of the already accepted mainstream art world comes strictly from the mind. And to me, yeah, the mind is part of it, but I care so much more about the gut and the heart. I run into problems with the art world when they just have a white canvas, or they have just a neon sign that says one word. And my heart and my gut just cannot digest what I’m seeing and has no connection to it. Supposedly the mind might make the connection —

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but Joe, their freedom is your freedom. As goofy as they want to get allows you the longitude to do what you want to do. So when you go into a gallery and you see the stuff and you wonder, you wonder why this banana peel is hanging on this canvas, that’s longitude and latitude for you to do what the hell you want to do. So in reality, you got to defend that character. When you go in those galleries and there’s a pile of sand there and it’s called “Untitled #3,” you got to defend that goddamn pile of sand because that’s the same world you want to function in.

COLEMAN: No, I agree with you there, and in fact, I had some sympathy for Marcel Duchamp. When he’s doing the freakin’ anti-art stuff, but do we have to live with the fucking Marcel Duchamp imitators for the rest of eternity?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but all this conceptualism and minimalism — They’re setting the foundation for me and you, Joe. Don’t you understand that? Things are changing, and they’re changing really fast.

COLEMAN: I just know what I hate and what I like. And I like your stuff, and I really am not so happy with what is happening generally with the art world but also Wölfli’s work should be seen, and Darger’s work should be seen. So if there’s anything that was good that came out of the outsider art movement, it’s that you got to see some great works of art that maybe would never be seen.

WILLIAMS: Things are really changing in our direction. They’re really coming around and pop art and graffiti are cartoon-related art. They’re just feathering our bed for the future.

An interesting thing happened to me. Let me give you this little incident. I was recently in a group show in Orange County at the Orange County Museum, and it was a set of five pairs of artists put together, and I got put together with Ed Moses, an abstract expressionist. And I thought, “Oh Christ, we’re not going to get along. We’re going to be at odds with each other.” So I gave as many concessions as I could that Ed Moses would put his artwork up with my artwork so I could get in this goddamn museum that I had no chance of getting in. So Ed Moses agreed to show with me. He had four paintings and I had four paintings. And the night of the gala for the thing, Ed Moses got up and starting bitching and moaning to the curator of the show that the lighting was terrible, that the lighting was designed for minimalist and conceptualists. So then I realized, here was the first time in my life that I find myself with this abstract expressionist as a brother. So what’s happening is the entire art world is changing and it’s changing radically. Juxtapoz magazine, 15 years ago, was not allowed in art schools. They just wouldn’t let it in art schools. It’s in every art school now; it is the number-one-selling art magazine in the world. It outsold Artforum and then it started outselling Art in America, and then it just finished outdistancing ARTnews.

WILLIAMS: These people in these museums have got to come to grips with this. They can’t hide from this. So Joe, me and you, all we have to do is just stay alive and watch our health —

COLEMAN: But Robert, it’s gone now. It’s kind of lost that touch of brilliance that it did have. And —

WILLIAMS: Well, the same thing happened with underground comics. Underground comics was bitchin’ when there were 25 people in it, but when there were 2,000 people in it, it diluted. The same thing is happening with alternative art now. There’s so many people getting in on it, it’s diluting. The core group is no longer the primary group anymore —

COLEMAN: But Robert, what I want to get away from is these terms … like even Juxtapoz is almost a term of an “-ism.” You know like surrealism or expressionism or impressionism.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, yeah.

COLEMAN: Juxtapoz is kind of an –ism. And I think we have to get away from that, and there should be great works of art beyond what is outsider or Juxtapoz or lowbrow. These are just things that are going to be used —

WILLIAMS: Well, Joe, your future is accounted for. You got it made.

COLEMAN: But Robert, these are things that are going to be used against us. They’re going to be used to try to fit us into a —

WILLIAMS: Of course they are. But how do you go around and stop it? There’s no way to stop this giant flow of young artists coming in. You can’t do it.

COLEMAN: No, but you talked about showing with some —

WILLIAMS: Ed Moses, an abstract expressionist. My paintings were shown with one of the top artists in the world.

COLEMAN: All right, but I did a show at my gallery, at Dickinson, that had old masters, and it had one of my favorites, [Hans] Memling. And I held my own with Memling, who is one of the great old masters that I aspire to. My works matched the old masters, and I care more about them than I do abstract expressionists or Marcel Duchamp or a lot of the people that maybe you are thinking too much about. I don’t think that they’re so important. I mean they may be important in the art world right now, but things change all the time —

WILLIAMS: They’re changing for your benefit, Joe.

COLEMAN: Yeah, the main thing is just do the work.

WILLIAMS: Watch your health and stay alive to reap the benefits.

COLEMAN: Yeah. I’m surprised I made it this far, Robert. [Laughs.]

WILLIAMS: I’m surprised I did, too. I’ve been such a fuck-up. [Laughter.]

COLEMAN: I agree 100 percent. [Laughter.]

WILLIAMS: Doing underground comics and pornography and hot-rod art and naked ladies and all this stuff. And trying to attempt to even be in the fine-arts world, much less take it over.

COLEMAN: I know, it’s funny. I’m glad we made —

KRISTY VALENTI: I’m curious about what Marc and Esther have to say about this younger-generation business.

COLEMAN: Sorry, you guys. I apologize. You two should speak your piece.

WATSON: Well, I think it’s really interesting because you do see a lot of new waves of artists and new trends come and go. But what’s really interesting right now is I feel like the power of the –isms is a lot more diffused because there's a lot of fragmentation going on, especially with people finding their little niche markets online. You can find groups who are very interested in your work no matter how particular or specific it is. And you kind of see that with Comic-Con. I know there’s a lot of people who are frustrated with where Comic-Con has grown and become, but at the same time I kind of feel like it represents what has been happening in the comics world, where it has become fragmented, and yeah there’s giant entertainment monsters taking over. But at the same time, you can find little gems here and there. And different trends and waves come and go. There’s really amazing artists who may have a four-year career span, and then they go off doing something else. But those moments that they’re around producing these little tiny print runs are amazing, and I love just collecting them for as long as they’re around and keeping them like little art pieces.

BELL: It seems like [the art world] is changing, and I guess it should. I sometimes wonder what’s going to happen not long from now. Things seem to be radically changing. There seem to be a lot of problems, like the decline of America for one thing. [Laughs.] Do you know what I mean?

WATSON: Yes. [Laughs.]

BELL: I think people are going to have to pick their corners and stuff will get sorted out. There’s a lot of stuff around — a lot of art is being made — and I suppose things will maybe be sorted out in the near future. And I think it’s good that there’s this sort of going back to craft — and craft in a good way, not craft in a bad way. I think it’s pretty interesting.

WILLIAMS: You know, I was listening to both of you, and let me put my two cents in. You know, the art world is not what you think it is. It’s not a pleasant environment. And it’s made up of people’s egos for a very little bit of money for so many people to try to grab. And there are hundreds of thousands of people trying to be artists and the thing is, there is such a slag factor of people trying to be artists and falling out of it. If you’re an artist for a while you realize that the hard times is actually your friend, because it eliminates these people that can’t make it. It’s almost a matter of attrition and fortitude to be an artist. This hurts an awful lot of people, especially sensitive people. You watch ’em come and go and be upset, you know. And the people that do make it have made it through really brutal politics and ass-sucking, and there’s just so many negative factors that you have to bring your own positive factors to the thing. You have to realize, everything is against you. Everything.

WATSON: Yeah I …

WILLIAMS: I didn’t mean to lecture you, it’s just an observation I had as an old man.

BELL: No, I appreciate it.

WATSON: Yeah, I appreciate it too.

COLEMAN: I’ve pulled a gun on ghastly people and I’ve bit the heads off live animals, and yet I survive. I continue to be treated even better than I ever expected. So, why does that happen?

WATSON: Someone once told me that, yeah, you just don’t quit [laughs]. You just keep going.

WILLIAMS: Well, you have to get so much into your art that you can’t take anything personal.

WATSON: You can’t.

COLEMAN: You have to be willing to do what it takes to express yourself. Even if it means getting arrested, even if it means doing something that’s gonna outrage everyone.

WATSON: Yeah.

COLEMAN: Robert, what do you think about what I just said? I’m curious about your reaction …

WILLIAMS: Well, you know, when I was working for Ed Rawls as his Art Director, I was involved in a three-day shootout with the Hell’s Angels and I was to shoot a pistol.

COLEMAN: Yeah but Robert, that’s not part of the art. I’m saying when it’s part of the art when I pull a gun…

WILLIAMS: Well, you know, it’s like romance. Each one of us walks down our own path. And I see some people just skim through and become millionaires and I watch other people just, you know, commit suicide. I just know what my life is and I just try not to hurt anyone else. I’ve watched you gain great international success, you know, and I’m very proud of you, Joe, but you’ve walked down your own path.

COLEMAN: I’m proud of you too, but what I’m saying is some people can just take a path that’s truly their own and if they just stick by it and don’t care what anyone else thinks and just stay with it, and it could beyond outsider or low-brow or anything else…

WILLIAMS: But people don’t do that. People go to art school…

COLEMAN: I don’t know about people, I’m talking about me! Who is “people”? I’m a person.

WILLIAMS: Yeah but, you know, if you go to art school they try to teach you how to be an artist and get through life and they teach you how to be an Abstract Expressionist or a Minimalist or a Conceptualist. They teach you what the hoard needs to know. So consequently, the hoard kind of kills itself. Me and you have been fuck-ups, so we found our own path.

WILLIAMS: Joe, you learn one thing in art school and that’s how to develop the confidence to present yourself so that they can’t pull the wool over your eyes. You learn how to use language and vocabulary that’s artistic in art school. You have confidence. Art-wise and craftsmanship-wise, man, you’re shit out of luck in art school.

COLEMAN: You ever look at a student show? Every single work looks like their teacher. And what the fuck is that? You’re not gonna learn a goddamn thing. You know? You gotta get in the real world and find out what, what you’re really about. Decide, if you’re ever gonna be a painter, maybe you’re gonna be somebody else. Maybe you’re gonna be, you know, a cook or a writer or a musician but you can’t go to art school and learn a goddamn thing.

WILLIAMS: You look at all these different celebrities that think they’re artists — have you ever noticed how they all look like they were painted by one person?

COLEMAN: Absolutely. And that one person’s mixed up.

DOOLEY: Esther, can I get your perspective on art school?

WATSON: Yeah. I am currently getting my MFA at Cal Arts, which is really difficult to balance while raising my 11-year-old and also having to pay my mortgage, doing editorial work on the side. And it’s really interesting. I always loved reading about art and theory before I went and it was really nice to be able to step away from the commercial world to the degree that I possibly could while paying my bills. I don’t have to make paintings and worry about having a show while I’m in art school. Right now, I’m just focusing on making paintings in school and exploring that. But it’s really interesting, because I do feel like I’ve seen behind the curtain of Oz and it does make me feel a lot more confident about where I am and what I’ve done. I’m coming toward the end; I graduate in May. I began feeling insecure. I began feeling like I didn’t have the language and I didn’t know very much … I don’t have a fine-art background — I have an illustrator’s, a commercial artist’s background — and so I started feeling insecure, but now I’m totally secure and confident about doing commercial work. I don’t have to be an artist assistant getting a little meager hourly wage. I can pay my bills with my art. I think that’s amazing. And then also to be able to have this time feels really special, to be able to explore and push my work a lot harder and faster than I could if I was having to worry about making paintings for my upcoming show — and they have to sell and it has to look good and it has to be written about and I have to present myself in a certain way. So I was able to really explore what it’s like to experience my art in person. That’s what I’m doing right now: making pieces that cannot easily be reproduced. You have to physically walk past them. It flutters and it moves when you breathe on the piece or you can crawl inside one of the paintings and see what’s on the other side or you can actually touch the paintings or pull pieces off of it that are comics that you can take home with you. And I feel like I was able to explore a lot of things that I probably would not have gotten around to. Maybe years from now, but I think I got there a lot quicker than I would’ve if I had not gone. But I also I feel like I got to study up on my art history, learn more theory. I feel like what that did for me is give me a strong base to make me feel confident about who I am and what I do and don’t.

I feel like I started off naïve, thinking I wasn’t fine-art enough. And now I feel confident that, no, I’m totally in the right place, doing what I should be doing and it’s totally cool if I’m making comics or doing an illustration for the New York Times or making paintings and selling them in galleries. It’s all OK. But it’s not for everybody. Even going to grad school. I definitely see that is not the route for everybody to take. Every art school is very different and what worked for me may not work for everybody else. We all take our own different paths and routes. I just happen to be somebody who was always taking writing classes or taking a postmodern literature class. I love to learn, so, this has just been fun.

DOOLEY: Now, Esther, Cal Arts certainly didn’t fit Robert’s description of an art school back in the late ’70s, early ’80s. Do you see Cal Arts today as fitting any of the descriptions Robert was talking about in terms of art schools?

WATSON: Well maybe not Cal Arts, because they’d probably be totally OK with what he did. But the other schools, yeah. I also teach a class at Art Center and that’s a very different school from Cal Arts. They’re training their students to acquire a very specific skill and they have a very specific standard that they want their students to learn. So that would be a very different experience. And I guest-spoke at SVA. I know it’s changed over the years. But I totally understand the story he related and it totally seems plausible even today at certain art schools.

DOOLEY: OK. Marc, I haven’t heard much about your background with schools. Could you fill me in?

BELL: Yeah. Well, I went to this high school where I’m from in Ontario. There’s a two-year program in art school, which was kind of great because it was free and it was OK. I ended up going to the University to get my BFA, but I dropped out because I didn’t want to pay the student loans. School’s kind of cheap in Canada, but still I just left. I switched to part-time in my fourth year so I went through the motions. I did everything everyone else did, but I was just paying half the money. That was my weird logic. But then of course halfway through the year the student loans people started getting after me because I wasn’t a full-time student. I was in the graduate exhibition and all that, but I wasn’t actually graduating. So I still don’t have my BFA and I don’t think I could go back to school necessarily. I thought about it but … what Esther’s doing is probably better: going back a little later because you get these students who are just going right from University right into grad school. It seemed so overwhelming to me. It’s something maybe I could handle now but I don’t think I could have handled it then. It just would have been too much. A good reason to go to school is maybe there’s a teacher there you were interested in learning from or being disillusioned by or something.

DOOLEY: So it sounds like you’re not particularly sold on the idea of art education from your own personal experience.

BELL: Well, it was a good experience in that I met some great people; some are my friends still. It wasn’t a bad experience, by any means. But it just felt like I was throwing money into something that wasn’t really getting me anywhere.

DOOLEY: I was going to bring up the whole idea of connections in school. Certainly, it was a big factor at Cal Arts. You know people who get into the field and they know and remember you as an advantage in terms of your career.

BELL: Who me?

DOOLEY: Yeah. Or any of you for that matter.

BELL: It wasn’t people I was studying under. I just made friends there that I’m still friends with. I went to a small Liberal arts university on the East coast of Canada. It’s a respected school. I guess it helped a little bit. I mean I did a show at the Mt. Alison University art gallery, so I guess it did help. There were positive things that came out of it definitely.

DOOLEY: So the networking opportunity …

BELL: Yeah, I guess so. For a long time after school, I was just doing my own thing and doing comics and stuff. I wasn’t really pursuing an art career.

DOOLEY: What’s your take on aspirations to wind up in the art history books, the established art history books?

BELL: Oh wow, [laughs] I can aspire to that. Someone else decides that. Whoever’s the editor of the latest history-of-art volume, I guess.

DOOLEY: Anyone else have a take on that?

WILLIAMS: About 20 years ago, Art Center started really focusing on their Fine Arts Department. And one memo got back to me that they were passing around at Art Center was: Nobody in the Fine Arts Department could use any of the power tools. You understand what I’m saying? The people in the Fine Arts Department were so sensitive and so inept that they’d hurt themselves. So that’s quite a statement. If you go to a comic-book convention and you’re walking in this big bunch of people and you just see a little 15-year-old kid, there’s a chance that that 15-year-old kid has better draftsmanship than someone with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree out of an art college. I’m not exaggerating. A kid that follows the comics has got a better chance of knowing how to draw than one that’s gone four years to art school. And that’s a good thing to say. The other point:

You can do more verbalization and narration with cartooning than you can with any other form of graphic presentation. You can stretch characters, you can violate time, you can do anything you want with cartooning. There is no way to stop cartooning in the future being a primary form of art.

COLEMAN: I would like to pick that thought up if you don’t mind. What I want to talk about right now is kind of metaphysical or somehow even supernatural. I mean, I’m always surprised and flattered and honored that people want to show my work. ’Cause I try to put so much out that I might be embarrassed about or might be arrested for. But at one point Whitney asked me what I wanted out of the art world. And I said I want a young curator who wants to make a name for themselves and is totally anti-establishment-art-world. I want that person. And then all of a sudden it happened. Susanne Pfeffer: her first show at the KW Institute in Berlin for her very first show she ever did. She totally got everything that I did and without any apology to anyone. So what I’m saying is you stick with your gut. And you stick with what you really care about and what you really love and your passion. And don’t give up anything, just keep going.

DOOLEY: Robert had a similar experience with his Helter Skelter show in terms of finding a curator who was willing to work with him.

COLEMAN: Well, I think it’s a good time for Robert and I. I mean he’s talking about things that almost seem clinical to me. Robert’s doing great stuff. But there’s a lot of people that are … I don’t like the Juxtapoz, it looks to me like high-school art. Robert is so much more powerful than a lot of the art that’s been produced from Juxtapoz and been championed. I mean Robert’s a serious artist.

WILLIAMS: Well, there’s just not that many good artists out there, Joe. And Juxtapoz developed a life of it’s own and pushed me aside. I could no longer control that monster. It got so big and it needed so many artists and there’s just not that many really good artists out there. There’s a lot of artists out there but they’re not that good. But yet the magazine is just growing like crazy. There is a need.

COLEMAN: I know. But that need is dangerous to what’s called art. What I’m saying, Robert, is you were subversive and I was too. And the more we get accepted in the art world is both a good and bad thing. I mean it’s good for us. But there is a lot of shit. Juxtapoz has nothing but shit right now. But you created something that had value and was really important …

WILLIAMS: You find me the artist that will substitute for that and I’m sure they would print it. They’re just not out there, Joe. You can’t find artists anymore that read EC comics when they were young. That’s over.

COLEMAN: It’s more than that. It’s way more.

WILLIAMS: It’s the age of big-eyed children. There’s nothing I can do about that. That world has left us. We’re in another dimension.

Mural by Juxtapoz magazine-featured artist Barry Mcgee, photo by Robert Brewster

DOOLEY: What does it mean that Juxtapoz is the largest-distribution art magazine that we have?

WILLIAMS: That’s not necessarily a good thing. I mean most of the shit that’s in Juxtapoz is garbage.

COLEMAN: Well, you haven’t looked in an Art Forum recently.

WATSON: [Chuckles.]

COLEMAN: Why don’t you grab yourself an Art in America and try and read it.

WATSON: I’m in this month’s issue. [Chuckles.]

DOOLEY: Of Juxtapoz?

COLEMAN: [Chuckles.] Go ahead, make your peace.

WATSON: Hopefully, there’s something good. [Laughter.]

WILLIAMS: Well, Joe, wade through an Art Forum some time. I’ll buy you one. You just sit down and read it.

COLEMAN: It really doesn’t mean anything. I’m still doing the same shit … they’re my passions. And sometimes it’s angry, sometimes it’s loving and sometimes it’s other emotions that I only describe in paint. But I’m forced to do these things. One time I was forced to do them in comic books. And I still love comic art. I love the idea of sequential art. But now I think the only way to really do what I wanna say is in painting. You know I’m starting on a painting right now that’s gonna take me three years to finish. That’s a giant commitment and I couldn’t …

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I’m bogged down on one myself.

COLEMAN: Yeah, and if I was back doing illustration or comic books, I couldn’t get someone to back me to do a thing that takes three years to paint.

WILLIAMS: [Chuckles.] Yeah, I hear you.

COLEMAN: I still cared about the work that I was doing when I was not in this place. It’s equal. But now I have the privilege of doing bigger and more amazing things.

WILLIAMS: I’m in the same boat with you. We’re both prisoners of our compulsion.

DOOLEY: Marc, are you satisfied with the attention that your art’s been getting, the coverage you’ve been getting?

BELL: Well, I look at magazines here and there. I don’t religiously read art magazines. I mean my work isn’t really written about that much. But yesterday, I found out I was written about in this magazine no one will have heard of here, Broken Pencil. And they kind of were attacking this show that I was in with a bunch of other people because we made a lot of zines of our artwork like cheap little zines of our artwork. And they were kind of saying that our work was part of the downfall of zine culture. ’Cause we had an art show of the original drawings that were in these self-published photocopied books and — “Oh my God” — they were selling them for $100 and $350, like the originals. So it was a pretty funny article. I kind of got a kick out of that.

DOOLEY: What was the show concerned with?

BELL: Well, the show was in London, Ontario, and it was called Not Bad for London, and it was me and a bunch of people I worked with. A bunch of people who were in that book called Nog A Dod that I put together, and the show was at a commercial art gallery, so it had originals from some of these books on the walls. So Broken Pencil wrote about it. It’s a magazine about zines, so they were saying, “What is up with these people? They’re selling their original artwork from their zines for hundreds of dollars. They were talking about how we were part of the downfall of zines as they were, I guess, in the ’90s or something. Do you know what I mean? It’s a little hard to explain. It’s pretty funny. And then it was also talking about this new thing happening where a lot more people, a lot of art students, are putting their art into zines and they’re more like art books. But the funny thing is, there’s been a long history of artists’ books as opposed to zines.

WATSON: Right.

BELL: Maybe they came out of different places, but anyway, you’d have to read it. It’s just a funny article.

Collection of 1970s punk fanzines. Jake

DOOLEY: Are zines artists’ books by another name, Esther?

WATSON: Yeah, zines have been called all kinds of things over the years. The surrealists and Cobra artists. There’s so many chapbooks, poetry chapbooks. There’s so many different forms of small publications. And there’s a whole history of people selling the work from zines. That’s a funny article.

DOOLEY: One thing that we haven’t touched on at all is the Internet. How has your work been affected by your ability to access the Internet and put your work on the Internet? Esther, we’ll start with you.

WATSON: Well, people see what I’m doing a lot quicker, which is kind of interesting, especially with some of my grad-school work. I had a couple of pieces up there, and then people were asking, you know, “I want to see more of that collage work.”

And I was like, “What are you talking about?” And then I realized they were referencing something I put up online. That’s a little interesting to me. It’s like they’re able to see into your world. And also, I feel like you cast long shadows on the Internet. People can see your history, whereas my work has changed over the years and I was able to move beyond a certain stage of my development and my work. Now, it’s like all online, you can see all of it, which is kind of interesting. I always think of some of my young students, what they put up on Facebook or Instagram while they’re still developing their work, if years from now they would be like, “Oh man, I shouldn’t have put those photos up online.” But I don’t know. I really like it. It’s nice to see what everyone’s doing, but it makes everything move so quickly. I feel like styles come and go really quick. Something feels old after you’ve seen it online so quickly. That baffles me. Even the idea of printing too has changed and is changing so fast, and teaching a publishing class … It’s bonkers because it’s almost like every three months we have to re-update what publishing is because it’s changing so quickly, whereas before we had all our lectures and we kinda knew what we were gonna say. Now, we just change it every single semester. Every trimester at Art Center I have to totally change the syllabus.

DOOLEY: And Marc, how has the Internet affected your career?

BELL: I have my blog, but I don’t really put too much on the blog, or I haven’t been recently. I just use the blog to remind myself of what I’ve done. But my stuff doesn’t really translate online that well. Like a book is one thing. It’s sometimes hard to look at my stuff in a book if it’s been shrunk a lot, and then the Internet, is probably not the greatest place for my work, because it’s so detailed. I don’t specifically design anything to be seen on the Internet, so it’s a little difficult. But I can’t say how it’s really affected my work. I mean, the gallery I show with will put work up there, so it’s kind of nice to get seen.

DOOLEY: Joe, you’ve got quite a bit going on with your website. How’s that working for you?

COLEMAN: Yes, there’s a lot going on with my website, but I really have no control over that. Catherine Gates controls both my Facebook page and joecoleman.com, so I’m never even there. So I really don’t know what goes on. Tonight, Whitney and I were both struggling with how we were going to do this thing. This is unique to us. We’ve never done it before. And I do know that I’m all over the Internet, but I don’t physically connect to the Internet, so this is really a unique experience for me.

DOOLEY: Robert, you have someone taking care of that sort of thing?

WILLIAMS: Well, I don’t have a computer for a good reason, but I have a website, and my website directs my business to my gallery in New York, Tony Shafrazi Gallery. I guess I get a bunch of hits and whatnot, and it’s got a lot of my art on it, and it keeps people posted on what I’m doing, but the computer’s one more thing I’ve got to stay away from, because once I had a computer, I’d be having to take on a lot more work than I can handle. Computers changed my world quite a bit, I guess. It sped everything up and made me feel a lot older than I am because I don’t have a computer. I’m kind of looked at like a hillbilly or something. Speaking of computers and how it does affect people, I was critiquing a graduate student at the college, and one of the artworks of this girl was she had a virtual life of herself, a secondary life that she created, and she had me watch this thing. And she was a fairly heavyset girl that was not all that attractive, and her avatar was this beautiful woman, this second self that she wanted to be. So she made me watch this avatar go through fashion changes and romance changes and all the things that she couldn’t be, and I got this really sad feeling about this. I was thinking, “Jesus Christ, this electricity, this thing has completely taken over this woman’s life.” And I had a long talk with her about the psychology of this thing, and I said, “Well, you know since this is going to be your second self, why don’t you have this gal join a pirate gang and fuck all the pirates or something?” [Laughter.] Really do something wild, you know. I don’t think that psychologically helped her. Anyway, I can see how this thing is not only taking over people’s lives, but it’s taking over people’s psyches. So I guess I’m better off the hillbilly. Did I answer your question?

DOOLEY: Yeah. And Robert, I mentioned the Helter Skelter before. If we’re talking about that area between cartooning and fine art …

WILLIAMS: Well, let me relate that Helter Skelter story to you. A curator at MOCA named Paul Schimmel started his tenure in 1992, and he wanted to start his career there with a big bang, showing all the remarkable artists in L.A. that had never gotten any exposure. So he called me up, and I don’t think he had any idea what kind of work I did. He comes over and looks at it and says, “Well, you’re in.” And my paintings are not derivative of any existing form or art; they’re just closer to underground comics than anything. And so I had 30 paintings on display and this enormous show that was internationally recognized with 15 other artists, and man, the feminists and the gays came down on me so hard. They picketed the show and they said my stuff was sexist and homophobic, and … oh, man, it was just the ugliest scene you could imagine. There were over 150 write-ups in newspapers all across the country, and all of them were negative except the one from The Washington Post. It said, “Walking through the Helter Skelter show was like walking through a Zap comic.” And of all the write-ups by all the art critics, they missed one very important point of that show: That was the first major show I’ve ever seen in my life — and I think that ever existed — where the majority of the work on display was in some way or another cartoon-related. And to me, this meant a big change in the direction of art.

DOOLEY: Joe? Have any of your shows been flashpoints for controversy in the way that Robert’s was with Helter Skelter?

COLEMAN: Are you kidding? My shows have been reviled. I was arrested for a lot of the shows I did. And my favorite arrest warrant that I have hanging in the auditorium says: “To Joe Coleman, aka Dr. Mamboozoo and his Infernal Machine.” I bit the heads off of live animals. And so they’re going into that in court. The rat bit me, and then I bit it back. What are you supposed to do?

DOOLEY: Justifiable homicide.

COLEMAN: Yeah, yeah. Homicide, right. [Laughter.]

DOOLEY: Now, I’d like to bring it up to galleries and museums today. Have any of you had any serious controversies with your gallery, museums, or exhibitions more recently or along the lines of making the news?

COLEMAN: Well, it’s kind of shocking to me that right now there’s the painting of Mary Bell in the National Academy Museum. You have to realize that Mary Bell was a little kid that murdered other children. I paint these paintings that are narratives, but they appear all at once. So Mary Bell’s whole trauma is presented on this really intimate, tiny, little wood panel. And the National Academy has decided that this is fine art. I’ve been fucking with everybody my whole life. It kinda cracks me up that Mary Bell, the little kid that was strangling little kids and killing little kids is now on exhibit at the National Academy Museum, the gallery that shows Andrew Wyeth. I’m kind of proud of the fact that I’ve said, “Hooray for me” and “Fuck you” to the art world over and over again, but somehow, I don’t know why somehow they keep me part of the play. I’ve gone to jail over my art, but I’ve never been arrested for anything that was not art.

I don’t know, I could be wrong, but I think there’s some validity about being arrested for art because it makes you attentive. I do think that anything you’re doing out of sheer tenacity and what you really feel is art. And I think that everything that you did, Robert, with Zap is art, but I think that what you and I did when we were doing illustration was not art. When you do it for yourself, then I think that’s the only thing that makes it art. It’s not for anyone but yourself. Do you feel differently?

WILLIAMS: I do in the respect that I think some of the greatest visuals which I would consider fine art were those pulp magazine covers done in the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s. Those real sensational covers. To me, those are just as much fine art as anything I’ve seen.

COLEMAN: I would say the same thing for really twisted films from that period. Like the stuff that Sam Fuller did. I mean, film is just as much art as painting.

WILLIAMS: Well, I started this conversation out saying that the premier form of art is film. You can’t beat film for art. I mean, that’s visuals and color and story and everything. But unfortunately, it takes a legion and a fortune to do it. So the second best thing to film is comic books because they have a narrative.

WILLIAMS: One thing I’ve noticed about the comics I didn’t like was the fact that the vast majority of the people who read the comics went through the pictures as fast as they could because the panels were just an expediency to get to the next panel. So very few people really had the eye to appreciate a good comic book. So when you’re doing a painting, you’ve got one isolated image there, they’re gonna have to deal with it. Do you understand what I’m saying?

COLEMAN: I think the whole discussion is interesting, but I don’t think there’s ever really an end to this discussion, because art keeps changing all the time. One day, we thought that photography was not an art. Another day, we thought filmmaking was not an art. And this whole argument about outsider or lowbrow is ridiculous, and I want to get off that point. I think that art is really just about what moves me. What do I care about?

DOOLEY: Esther, how do you see the fine-art world changing as you graduate from Cal Arts and pursue your career?

WATSON: I actually think it’s a really great time right now. Coincidentally, I’m working with comics and painting, and its totally being accepted by my peers as valid art. And actually, in this month’s issue of Artforum in the mail yesterday, there’s this really amazing article called “Opening Lines,” and it’s about the drawings of Ad Reinhardt, who painted the black paintings. And he has these really amazing cartoons that critique the art world. I really think it says a lot that they’re digging up his cartoons and talking about them again, and not just talking about his black paintings. I think that says a lot about our time. And actually, it’s really interesting at Cal Arts. I get a lot of interest and attention about my comics and the little zines I’m handing out, and sometimes there’s more of a discussion about the comics than the paintings. So I think it’s a really great time right now, and I think people are really open to a lot of things. There’s just a big mix right now, a whole combination of high and low getting all scrambled and turned around, and what was once low is now high, and it’s all just getting turned around. Just keep doing what you love to do.

DOOLEY: And to what you attribute this shift in attitudes about comics, would you say shows like the Masters of American Comics have made a difference?

WATSON: Well, yeah. And then there was also the Comics of Abstraction show in 2007 at MoMA, and at the Whitney Museum there was the Fine Art of Comics, so you’re starting to see over and over museums embracing and legitimizing comics as a higher art form. I think they always were. I mean, Ad Reinhardt was making comics back in the ’30s. It’s been kind of brought up into the art world over and over and over, and now I think it’s way less shocking to see comics in a museum.

DOOLEY: Marc, what are you looking forward to happening in the future?

BELL: Well, I can’t say I know what’s going to happen, but I guess I have two minds about it. I agree with Esther: It’s great that this stuff is being accepted, like the kind of art we all do here on the panel. We’re accepted on different levels of course, but I guess I’m of two minds. Comics being accepted is great, but I also think comics have sort of thrived as kind of a gutter medium in a way, and they’re sort of becoming this mainstream thing with the graphic novel, yada yada. That’s good, and then I also think there’s another side to it. I guess all I mean to say is I think comics are good as kind of a crappy medium. But yeah, I pretty much agree that maybe this long line of minimalism and really dry art is kind of falling away, and this other stuff is coming out. Yeah, it’s an interesting time, but I can’t really say I would understand where it would go.

DOOLEY: And in terms of the line, do you see groups like Fort Thunder, Paper Rodeo, the Kramers crowd as also helping to make a difference in terms of how comics are viewed as fine art?

BELL: I’m not sure if it really matters to me if comics are considered art, but if it opens up things in a general way, it’s a good thing, it’s an interesting thing.

DOOLEY: OK. And Robert, what’s the view from where you sit?

COLEMAN: You skipped over me.

DOOLEY: Yeah, Joe first and then Robert. We’ll let Robert have the last word.

COLEMAN: I kind of like the idea that art is always in flux and keeps changing all the time, and whether it’s impressionist or expressionist or realist, I don’t really think that I care that much about what’s happening. I really only care that right now, there’s a lot of people that jump on board, and they care about this interesting thing that I’m doing. I’ve never changed what I was doing. I mean I’ve always painted whatever I’ve wanted to paint. To me the only way you should ever paint or produce art is “Hooray for me and fuck you.”

DOOLEY: Robert, you ready to follow that?

WILLIAMS: That’s pretty dramatic, but I’m gonna make a try at it. There’s two parts of our conversation here. Let me end on this: We’ve watched comic books from the ’30s become so serious that they’ve influenced the movie industry to a giant scale. You can watch that span of change just with comic books. Now as far as comic books as art, there was a curator named Walter Hopps. Walter Hopps is a good friend of mine, and he died just two years ago. He was designated in Europe and by the museums in this country as the No. 1 museum curator in the world, so there’s no question about that. But he was way, way ahead of his time. He made all the top artists, Ed Ruscha and all the artists on the West Coast back in the ’50s and ’60s, gave Andy Warhol his first show and Duchamp, the first American show here. He was a very, very important curator. In 1970, Walter Hopps had a Zap comic-book show at the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C. Now you have to understand, Zap Comix was only three years old. Who in the hell in the art world ever heard of Zap Comix? You know what I’m saying? So comic books had a fine-arts footing clear back into 1970. If you go to Europe and you go to a comic-book shop, it’s like going into a mortuary. It’s solemn, it’s sacred. It’s not like over here. A comic-book shop in Europe has a whole different serious attitude. They’re taken very serious in Europe.

An odd thing happened 30 years ago, comic-related, in the fine-arts world, and that was the appropriation of comic-book panels into paintings. And this really, in my opinion, was a slap in the face of comics. It brought comics to the presentation point of being art, but the artist that copied comic-book panels did it in an indifferent way. In other words, if you find pop art, and it’s a copy of a comic-book panel, you’ll notice that there’s an indifference to the comic-book story. It’s done as a decoration. That piece of artwork is now a decoration. And it really, in my opinion, has taken away from comics. Now, a lot of people say, “Well, that’s one of the things that brought comics to the forefront, but …”

My first point was about the comics, but my second point: I have watched the cartoon be more and more involved in art. It’s gotten to the point where it’s almost accepted. There’s maybe a hundred, maybe more, galleries around the United States and Europe and Japan that have art that’s cartoon-related. It’s been an evolution I’ve watched happened, and it’s partially from comic books, and partially from movies and whatnot, and a resistance against abstract and conceptual art. But there are some problems, some real problems with it. One problem I mentioned earlier was that to make a lot of people happy with the art, and for the artist to make money, if you start doing sentimental tripe, you have a great deal of success. There’s a gallery in LA called the CoproGallery, put together by a good friend of mine, Greg Escalante. And I asked Greg, “Why do you have these big-eyed children and all this sentimental crap?” and he says, “Because that’s the stuff that sells.” Now I’m on the other side of the fence with representational cartoon art. I like the drama and energy, pathos, adventure … I like art to be lurid, I don’t like art to be a decoration. The wonderful thing about abstract expressionism was it looked beautiful in a bank lobby. It looked wonderful in the hospital waiting room. But it said nothing. It just did well with the décor. The problem with representational art is it challenges its environment, and you have to get away from the idea that the art is going to have to congeal and integrate into an environment. I think the whole fuckin’ environment ought to be designed for the painting.

COLEMAN: You’re right. You’re right, Robert. I agree with you a hundred percent.

WILLIAMS: There hasn’t been a generation but probably our generation coming up that has seen the virtuosity and viability and flexibility of cartoons. So if you’ve got one generation doing cartoons imagery and abstract thinking in cartoons, then the next generation coming up will take that another step. But you’re not taking any fucking thing another step if it’s big-eyed children and funny pets, see? I’m really hoping that the generation that comes behind us is serious enough to understand cartoons, comic books, the ability to make cartooning such a flexible and maneuverable and malleable medium. To take it one step beyond my generation’s and then one step beyond that. In other words, my generation won’t understand what the next generation’s doing, and the next generation won’t understand what the generation after it’s doing, because they’ve taken cartoon imagery and progressively advanced it. That’s what I’m hoping. I don’t see that happening, but that’s what I’m hoping.

Cartooning and fine art is here, and it’s going to get bigger. Which direction is it going to take, I don’t know. Is it going to be sentimental slop from Margaret Keane, a descendant of Margaret Keane’s art, or is it going to be truly mind-expanding conceptual graphics? We’re at a crossroads there, and it’s in the hands of the people in the future. I don’t know what the hell to do. I just do want interests me, so I’d have to leave the conversation there. Our period of history now has been the most flexible and had the most chance for opportunity in art that I’ve seen in my 50 or 60 years in the arts, and it’s just a wonderful time to be an artist.