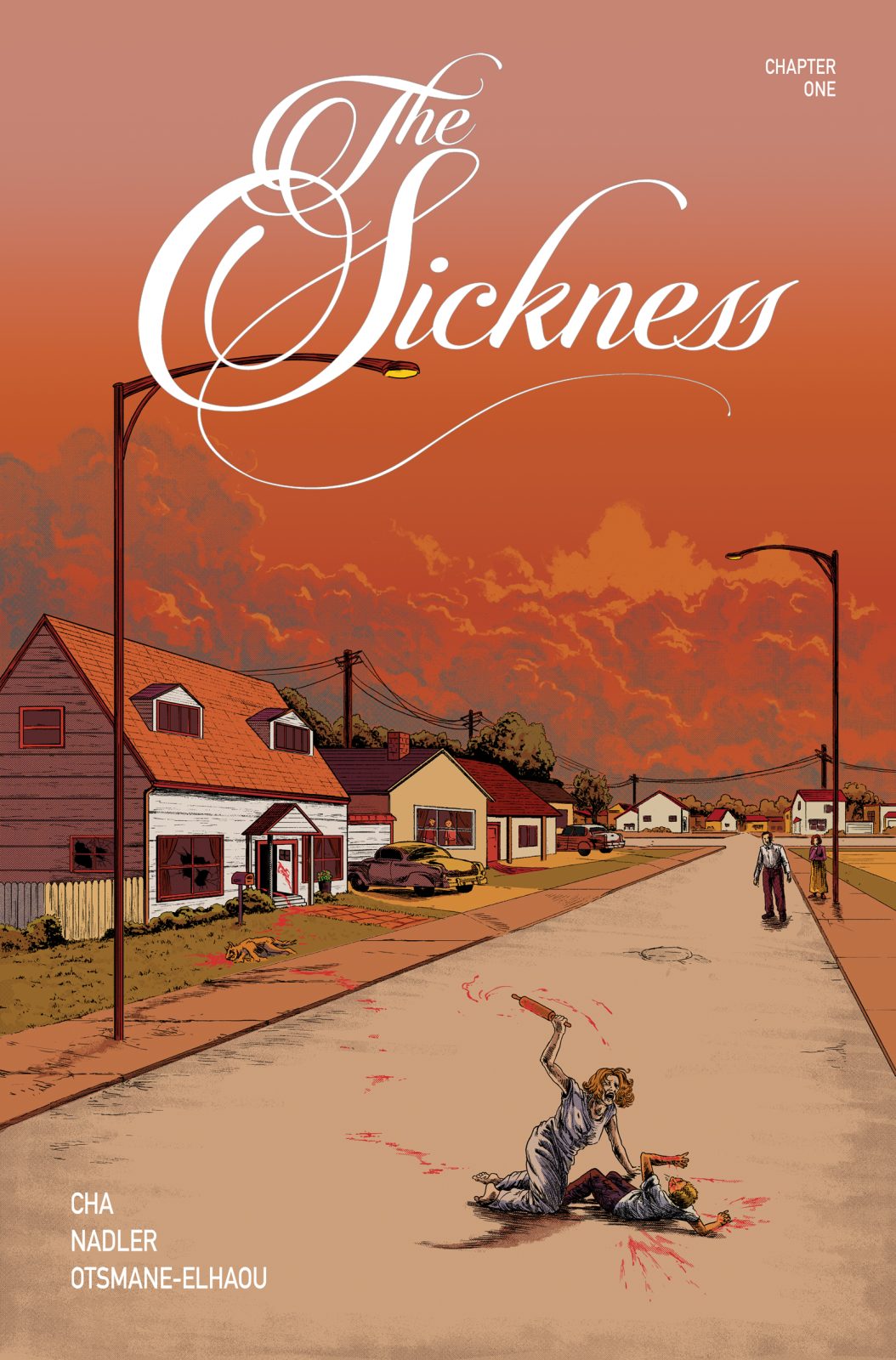

Lonnie Nadler and Jenna Cha are a creative duo I check in with often. I've been following Nadler with interest since his first professionally-published comic, The Dregs (Black Mask Studios, 2017), with co-writer Zac Thompson, artist/letterer Eric Zawadzki and colorist Dee Cuniffe. Cha I've followed since her published debut, Black Stars Above (Vault Comics, 2019-20), colored by Brad Simpson, lettered by Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou and written by Nadler. Their latest collaboration, with Otsmane-Elhaou back as letterer, is The Sickness. A horror story epic in both scope and length, The Sickness spans several distinct time periods and a projected 14 comic book issues from Uncivilized, following the veteran graphic novel publisher's similarly expansive presentation of Craig Thompson's Ginseng Roots. The first issue is available now.

I sat down with Nadler and Cha at the beginning of April over Google Docs to discuss their approach to horror, their thoughts on publishing, and the broken lens through which we view the world. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

-Hagai Palevsky

Hagai Palevsky: Let's start at the beginning. How did you both get into making comics, individually?

Lonnie Nadler: I have loved comics since I was a kid. I grew up in Ontario, which is a bilingual province in Canada, so I was in a French immersion program in school. I was bad at reading and writing French, so when we had to take books out from the library, I always took out Tintin and Asterix comics. That cemented my love pretty early on, and then from there I got into superhero stuff. Then in high school I started reading more indie books and '80s Vertigo, and once I found those it was like a light went off in my head, and I told my parents at some point, “I want to make comics.” Obviously, I consumed comics a lot throughout my youth, but it wasn’t until university that myself and a couple friends started making zines together and selling them at art fairs and indie comics festivals. We just self-printed those and made maybe like half a dozen or so in a year, and I really never stopped after that. As I got better at understanding the medium, my ambitions grew as well, and I wanted to make longer-format work. The first “real” longform comic I did was a book I wrote called The Portrait of Sal Pullman, illustrated by Abby Howard. From there I went on to learn more about traditional publishing and started putting pitches together with other people I had met in the industry through the comics journalism work I had been doing. Thankfully, Matt Pizzolo, the publisher at Black Mask, took a chance on one of those pitches, The Dregs. Nobody else wanted it because it was quite… gruesome, as far as pitches go, so I’m forever grateful for his willingness to accept “unproven” talent into his roster. And after that I just tried not to lose momentum. It’s worked out okay, I guess.

Jenna Cha: Like with most creators, I also grew up loving comics since I was a little kid. During my childhood, my understanding of comics was exclusively Calvin and Hobbes, and I would waste reams and reams of my family’s computer paper on silly cartoon strips that tried to emulate C&H’s format and humor. (Sometimes I also bring up Garfield being my other obsession, sometimes I don’t.) It was really since I could hold a marker that my artistic self-expression was almost entirely through sequential art. It wasn’t until I was in middle school when I was accidentally, unwittingly and unwarrantedly introduced to Junji Itō - by this time, I was still in the part of my life where I was scared of everything to an immobilizing degree. Seeing panels from Uzumaki straight-up traumatized me, and stayed with me burned into my brain for a long time. But nevertheless, it was a major transition into how I saw comics, let alone horror comics, which I didn’t expect would be my source of Stockholm syndrome for years to come. Jumping forward, when I was 21 I discovered that the Minneapolis College of Art and Design had a comic art program, and it really wasn’t until then when I considered comics as a “viable career” (I have since abandoned this sentiment).

If I recall correctly, Black Stars Above was not only your first collaboration, but Jenna’s first formally-published comic. How did that come about?

Cha: FATE.

When a J.C. tells me about fate, I tend to listen.

Nadler: I feel like this is an infamous story at this point. Jenna, do you care to tell it, or should I?

Cha: We have to share the load as a—spoilers—married couple. So, your turn.

Nadler: Alright. I had pitched Black Stars Above to Vault and they greenlit it based on my written pitch alone, and there was no artist attached. Once we were getting ready to begin production, the search for an artist began. As you can probably tell from my past work, I’m quite picky about who I work with. Adrian [Wassel, Vault editor-in-chief] would send me lists of names, and I’d send lists back to him, and basically that wasn’t really going anywhere fast. At the time-- and this was like, what, three or four years ago now? I used to spend hours patrolling social media for new comic book artists. I would just doomscroll, but with some intent, so I felt like I was doing something useful. Whenever one of those hashtags would come about like #PortfolioDay or #VisibleWomen, I would just look through as many as I could. One of those times I happened to stumble across Jenna’s Twitter from a #VisibleWomen post she made with some of her hatchy body horror panels, and then I looked at her Tumblr page and I was like, “Uhh, holy shit. How does this person not have a bigger following?” I emailed Adrian immediately because her style felt way more old school than how most young people draw these days, and that was exactly what I was looking for with Black Stars Above because it’s set in the late 1800s, and I wanted the art to feel like it matched the era. After I emailed Adrian, he replied quite literally one minute later saying, “Dude, I just was typing an email recommending Jenna.” So, I think that’s what Jenna means by fate. Serendipity, I prefer, but I guess that depends on your beliefs…

Cha: I had been in contact with Adrian around the time Lonnie was scouting for artists because I did a short backup comic for one of Eliot Rahal’s books over at Vault. Eliot and I had met just a few months prior at a convention in Minneapolis, and he asked me to draw the backup. I consider him a good friend, so I am allowed to make him as uncomfortable as possible at any opportunity when I say that he is 100% responsible for my comic career. And my marriage. Send all your complaints to him.

Nadler: Oh, yeah. A year after Jenna and I started working together on Stars, we got married. So, I guess that’s also part of this so-called “fate.”

Cha: That ol’ jaunt.

Has that connection also affected your collaborative dynamic, or do you keep these two aspects of your life relatively separate? For one, I'd imagine that sharing a permanent physical space with your collaborator must have some bearing on how you view the process.

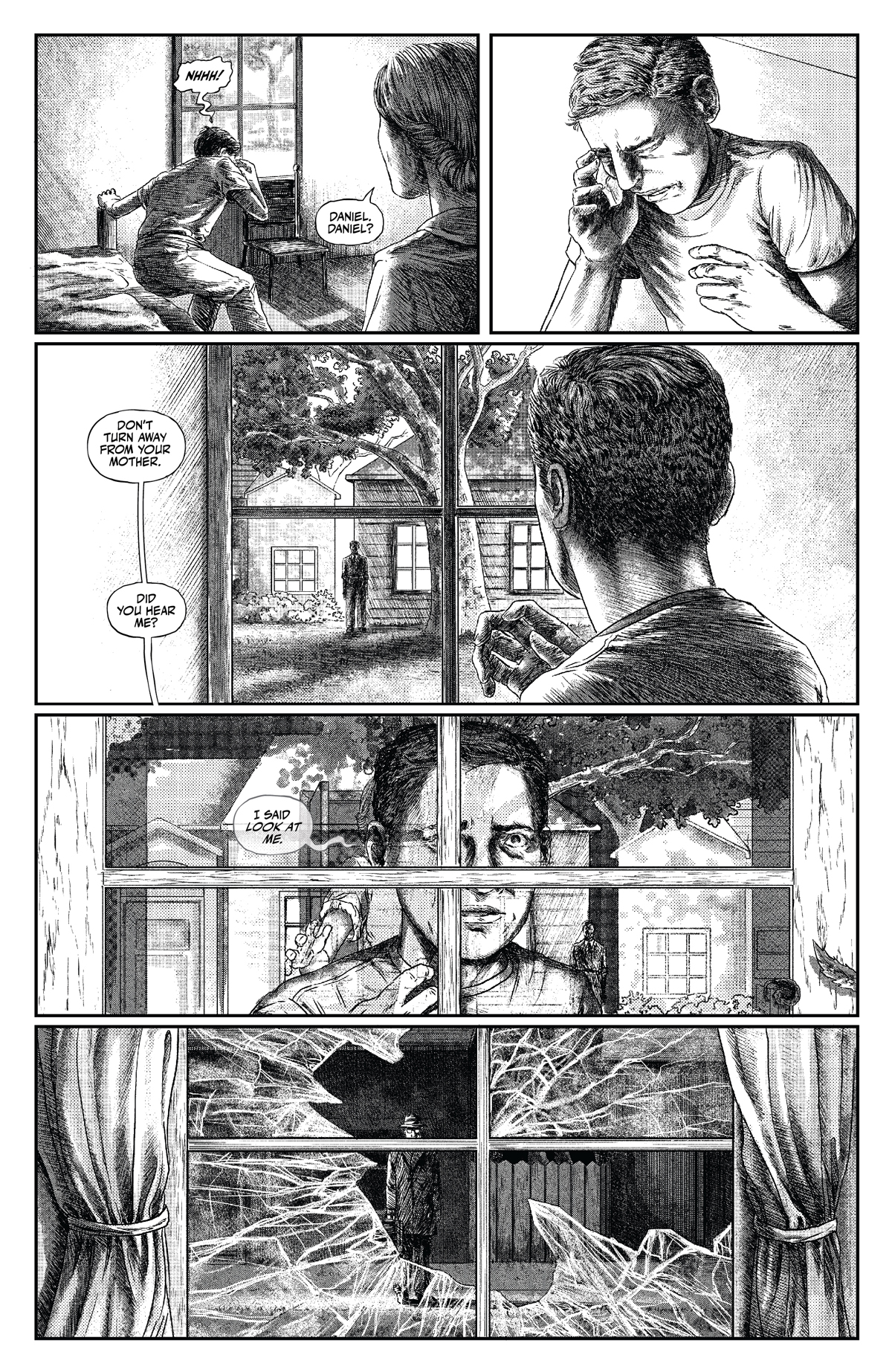

Cha: It’s kind of impossible to separate the two things; we both work from home, and we’re just a few paces away from each other for most of the day. When we write the script for The Sickness, we sit on the couch next to each other for hours, then we take breaks and go to the kitchen together and talk about the comic, then we go back to the couch and write some more, then we go to Walmart together, then we etc. etc. It’s honestly probably the only way we could get our collaborations going - being in the same space at all times. Our attitudes, approach, and processes are pretty similar, and we share a lot of philosophies about comics, so when we work together it’s very much a melding of minds.

Nadler: I don’t have much to add other than it’s very fulfilling and I know we are fortunate in our circumstance. Another thing we do, after the script, is sit down together and work on the layouts of the pages. Not many writers get to have that close of a collaboration with artists, and I think it makes the book much stronger for it. We can just so easily get on the same page.

Cha: It’s a blessing and a curse. A very big problem is that we enable each other’s desire to overdo stuff, and it’s hard to be the one who says ‘no’ to something insane.

Well, I mean, I don’t know that I consider that a problem, but I suspect I’m more receptive to indulgence than the market typically is.

Cha: It’s a problem in that even the freedom of 14 issues isn’t enough to contain all our bullshit.

Nadler: If we were really allowed to let loose then our book would be completely unmarketable.

Are there any limitations or constraints that the publisher has asked for, or is it all just your own sense of, “Oh, hang on, we probably shouldn’t go that far”?

Nadler: At Uncivilized, there are literally, and I mean literally, no constraints. Tom [Kaczynski], who runs [Uncivilized], is a prolific cartoonist himself, and he understands and values creative freedom. Truth be told, this is exactly why we wanted to publish with Uncivilized. Jenna and I had brought the book to a couple other publishers before Unciv, and all of them asked us to change the book. Not just in little ways, but major ways that would have utterly compromised the integrity of the work. For example, we pitched it as a 14-issue series and one publisher said, “We like this, but can you do it in four issues?” That was such a wild request to me, and it honestly made me depressed for the state of the industry. But when we brought the pitch to Tom and said, “Okay, this book is 14 issues and most of them will be 30 pages long,” he hardly had any reaction. It was just “Okay, that’s cool. We were looking for something longer-form in our slate anyway.” While it is a huge risk in today’s market, we believe there is room for longer, more transgressive comics, and that only ever doing miniseries is ultimately way too limiting and bad for the general health of the industry at large, both creatively and from a business perspective. But I have no MBA, so what do I know?

I do find it noteworthy that, for such a sprawling project, you went with a fairly small publisher - which is not meant dismissively, I love many of Unciv’s books. It’s a vote of confidence in the project, but I can’t imagine it being easy to make that decision once real-world considerations are taken into account.

Cha: I’ve known Tom K. for a while now; he was one of my professors at Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and I briefly worked at the Uncivilized office, as what I described as their Mail Goblin. Since he’s known my work for this long, he’s told me that the door is open for sending him pitches. I’m going to be brutally honest, I was hesitant to pitch to Uncivilized because I didn’t think my work was “artistic” enough to meet the standards of the world of indie comics. I still have doubts when I see my work beside Gabrielle Bell and Noah Van Sciver. As we were pitching The Sickness to various publishers, we knew the whole time that Uncivilized was one of the only actual fully creator-owned publishers.

Nadler: To be clear, fully creator-owned is not what the vast majority of publishers are out there who claim to be “creator-owned.”

Cha: It is Uncivilized's philosophy that they’re trying to make good comics; they don’t care about IP, or making things bite-sized. The fact that they are small, ironically, I think allowed them to make something bigger, because they don’t need as large of sales to justify the risk.

I don’t know if you both are aware-- I don’t know how online you’ve been over the past couple of weeks, and how much attention you pay to that kind of sphere, of the little discourse happening surrounding the benefits of traditional publishing in the more indie/small press circuits, after Joshua Cotter’s posts about sales of his series Nod Away. I’d be happy to hear your experiences with publishers, and if you have any thoughts about publishing in a frankly rather precarious sphere.

Nadler: I did see Joshua’s posts. To be honest, I prefer not to comment about it because I do not know the details of the issue, nor anything about how Fantagraphics works in terms of marketing and publishing.

That’s fair. It does appear to me, too, that there has been, especially since COVID, something of a reevaluation of the periodical single-issue format and its supposed necessity in mainstream/direct market comics, so I'll admit that when the announcement hit and you said "14 issues," I was impressed, both because of the scope and because of the dedication to format.

Cha: Yeah, we played with other format ideas, like a full graphic novel, or a two- or three-volume series of novels, to read what the market was leaning towards. Fourteen single issues have the benefit of basically constantly marketing your book on a bi-monthly basis. I’m extremely naïve when it comes to this stuff; in my mind whenever I’m constructing a book, I’m like, yeah, 20 issues sounds good. Four hundred pages for this graphic novel should work. I have a very weak and ghoulishly uncompromising perspective when it comes to the logistics of publishing - I just want to make the damn thing.

Nadler: I think it’s important to state that we are not conceited enough to think we have all the answers regarding publishing and the comics industry. But for my own sake, and the sake of my friends and other creators who I speak with, I have to believe, I have to believe, that there is a market for this kind of long-format genre work in comics. This kind of story has a huge audience in Japan, and we see manga becoming increasingly more popular in North America, so we know it exists. It’s just a question of how do we entice readers and shops to support books like this? Maybe The Sickness will be a huge fucking flaccid failure. But for my own sake and my own beliefs, we have to try, and we have to do what we believe is ultimately the best thing for the story and our vision and hope that it lands.

Jenna, you've done your own writing in the past, including in the self-published Baby Rose Marie the Child Wonder Sings 'Come Out Come Out!' (one of my favorite comics of last year), and, Lonnie, it was during the pandemic that you taught yourself how to draw comics with Where Lost Dogs Lie. Does knowing the particulars of your respective counterpart's work affect how you approach your own part of the book? Or is there a sort of 'stay in your lane' division?

Cha: There’s honestly almost no division; we’re constantly swimming in each other’s lanes. There’s a reason we’re listed as co-writers/co-creators [on The Sickness], our roles are not mutually exclusive. I do think that knowing Lonnie’s writing tendencies does allow me to trust him a lot and surrender the book to his understanding of formalism, which is one of the biggest assets of the series.

Nadler: I think the fluidity stems from what we mentioned before. We live in the same space, and we both think about this story all the time. When we write, it’s both of us equally sharing that duty. We literally sit beside one another and script it panel by panel. We talk about ideas and do research on our own, and then come together. Even the art is somewhat collaborative. Jenna obviously does all the heavy lifting in drawing the damn book, but I will often come look at a page and say, “Oh, that looks good. What if you add this panel here, or maybe you could include so and so in the background of that panel?” To really answer your question, though, I think a writer must understand what an artist does in comics, and vice versa. I would encourage all writers or artists to dabble in the other side (moreso writers). It enriches your knowledge of the medium. Personally, I can’t imagine scripting something for an artist if I didn’t have comprehension of that side of the form myself. The medium is founded on the marriage of text and image, and learning how the two complement and contrast one another is essential.

I know that The Sickness was a project that started as a solo project by Jenna, even before Black Stars Above. What prompted you to revisit it? Or was it something that was always gestating in the background?

Cha: Talking about this is always funny to me. It wasn’t more than I think a week—maybe a few days—after I officially signed on to Black Stars Above, when I had texted Lonnie and asked “I don’t know if this is, uh, allowed in comics, but how do you feel about the artist pitching a story to the writer?” Lonnie was immediately like “Yes please.” So I had sent him probably the worst pitch document anyone had ever written - it was like 5,000 pages long, all over the place, and thank God I didn’t ever send it to an editor. Lonnie is who I’d call The Pitch Master, so it probably hurt his soul to read all of it.

Nadler: I am the master of writing unmarketable pitches. “It’s Żuławski's Possession meets Leave It to Beaver. What do you mean you don’t want to publish that?!"

Cha: During Black Stars Above, we sort of poked at The Sickness every so often, and, yes, it was definitely gestating in the background the whole time on my part. It wasn’t until the last issue of Black Stars Above when we were like, alright, let’s do this. By that point I had moved to Vancouver and we were beside each other, so the need to get to work on this together was like a firecracker.

I think there's a tendency, in discussing artistic influences, to sort of reduce "I am influenced by X" to "I like this person's work and so that might shine through," but are there any particular elements of The Sickness that you've looked at and thought, "Oh, I know where this came from, this is clearly influenced by [whomever]?"

Cha: Yeah, I think one could read The Sickness and think, okay, this book feels a bit like From Hell or Monsters in some ways. It’s true, those books are definitely inspirations, but we never really set out to do something with “Let’s make this look like X,” like you said. I think the question is hard for me to answer; I’m not super-introspective about my work in that way, and I don’t consciously look back and think about where this or that comes from in terms of influences. Lonnie and I are definitely conscious about specific things that do inspire us for specific sequences or layouts or whatnot, and we are vocal to each other about why these things are inspiring. This is going to sound pretentious as hell, and I apologize, but, if I am introspective about my work, it’s more in terms of what events in my life inspired this or that. My process in coming up with stories is a matter of things coming completely out of nowhere and I feel compelled to obsessively build on it. I put trust in my process, in that a story will have to incubate for years before I realize what it’s “about.” This doesn’t mean I’m constantly trying to make things make sense in a thesis, but rather over time I’ll kind of realize that, okay, this is what I was going through at this point in my life, and this is how my brain is trying to cope with it.

Nadler: When I was a younger writer I used to sit down and try to emulate my heroes and influences, but that’s how everyone starts and learns, and that tendency, hopefully, peels away one project at a time. Like Jenna said, Barry Windsor-Smith’s Monsters and From Hell are obviously sources of inspirations, but we didn’t try to emulate those directly. And while those are influences, The Sickness, I would say, is equally influenced by Stephen King, Junji Itō, David Lynch, Flannery O’Connor, and mid-century American cinema like Hitchcock’s Vertigo and The Night of the Hunter. That’s, in my mind, how most artists create. We are sponges, and certain stories get soaked up more than others due to natural inclination and affinity. And what comes out will always share some spirit with those sources that inspired us to make art in the first place. Hopefully by this point in our careers, however, it feels like we are moving beyond influence and into something even marginally original, even if that can never entirely be the case. That’s the goal at least.

Jenna, between The Sickness and "She's Got It" [from Tiny Onion Studios' Razorblades: The Horror Magazine] with Lonnie and Baby Rose Marie, which you did on your own, you appear to be compelled by the aesthetic mindset of 20th century Americana. Of course, this is part of, by now, a well-founded tradition, from Lynch to Al Columbia to those influenced by both (or either, or neither), but still I wonder - what it is that compels you about that framework?

Cha: I think old cinema and the aesthetics of mid 20th century American culture came from an early part of my life, because my parents loved all that stuff. The first real dose of cinema I got was when I was maybe 12 or 13 and my dad told me to watch Psycho when it was on TV one night. I think something about the familiarity of how the world looked clashing with the off-kilter way of how people acted spoke to how I viewed the world, as an extremely anxious and lonely kid. I also just, for some reason, loved Alfred Hitchcock’s directing. He became the beacon of my infatuation for old movies, along with Akira Kurosawa. I also want to credit the Castro Theater in San Francisco for reinforcing my love for old movies; that theater was like a place of worship for me, somewhere where I knew I could always go to, and I was introduced to a lot of really influential old movies.

If I could point to two things I always thought about growing up, it was old cinema and horror. It was only a matter of time until those things became mashed together in my brain - the veneer of Americana, the pristine and faultless depiction of America, visually clashes very well with horrific disgusting images of terror. There was a point in my life where I had to come to terms with the fact that all my inspirations came from an absolutely nightmarish time period, one that was in fact not that long ago. Having to face the reality that it’s more of a question of-- shit, who didn’t assault someone in Hollywood around that time, or who wasn’t exploited when making this movie… it’s hard to revisit all those things I love. So, The Sickness and all my other weird Americana-horror stuff comes from a real deep frustration of recent history, and indulging in tearing apart the pristine glossy way in which history is presented.

Similarly, Lonnie, over the time I've followed you you've written in various genres from Marvel superheroes to neo-westerns to fantastical family drama, both alone and especially with your writing partner Zac Thompson, but I don’t think I’d be too far off in assessing that you feel most at home writing horror. What draws you back to those places?

Nadler: Not unlike Jenna, I was also a very anxious and scared kid. I hated being alone, and doing anything that entailed such filled me with angst. I don’t think that fear ever really leaves a person, but deep within that, there was also a curiosity about the “darker” things in life. The shadows, closets and attics are clichéd horror spaces for children, and these things terrified me, yet simultaneously I wanted to understand what might be hiding there. Some of that carried into my adult life. I’m trying not to bounce all over the place, but I think some of my affinity for horror is also tied up in growing up in a fairly religious Jewish house. You are told what is “sacred” and what is “good” and what is “bad.” And all of that, you are told, is older than time, and it’s equally vague and mysterious to me. So, I think horror relates, in that it is rooted in this sense of unknowing and ignorance, and when you become scared of something you almost divorce yourself from reality - you are put into a nearly spiritual place where rationality goes out the window. You suddenly believe in witches, and ghosts, and demons, even if you tell yourself on a daily basis those things don’t exist. I think Guillermo del Toro said something along the lines of this: horror, while it is seen as profane, is actually closer to being sacred as a result of this phenomenon. It reduces everyone to the same level, regardless of beliefs. I’m sorry if this answer is a bit all over the place, but I hope it makes some sense. Horror for me is just kind of ingrained in who I am, and even though I’m an intensely rational person, and an atheist at this point in my life, the genre appeals to me because of its ability to draw back that curtain of logic and pragmatism. I’m not sure what that says about me, but I’m sure a therapist would have their heyday digging into all this.

I didn’t know you were raised religious. I assume that that’s not a major part of your life nowadays.

Nadler: I have a very complicated relationship with Judaism, that has only grown more complicated over the last few years. If forced, I would identify as a Jewish Atheist, whatever that means.

This makes sense, though, in that there's always a speculative element to the horror in your work, together or apart; your horrors either come from an extra-human force or, if they are done by a person to a person, either the means or the end is something that is bigger-- that is outside the scope of what we know human life to be. Would you say that you're more interested in a horror of particulars, one that is anchored in a specific locus and circumstance, or a horror of universals, of organizing principles?

Cha: Personally, I would say my sentiments toward horror comes from a horror of universals. If we’re talking about religion/beliefs, I could chime in and say I was raised Buddhist, so my perspective of the world is very much about connectivity and no stone unturned in terms of how one thing relates to another. I find comfort in this, personally; in a strange way I find comfort in the universality of horror. The way I approach horror as a lens over society or broken systems helps me better understand history on a human level, as well as coping with how I see myself in relation to these things.

Nadler: It’s a fascinating question, and as analytical and academic as I am as a person, I honestly try not to think about this kind of thing in my work. I think for me, it is a bit of both. Much of my work is about people or characters who are divided between two worlds. Usually that entails something related to the individual horrors of circumstance, and then some larger, more primeval horrific truths that they inevitably come up against. The Sickness is, intentionally or not, kind of about these two aspects of horror. Without getting into our themes too much, I believe there is some link between the two. Or perhaps that is just so in terms of how humans perceive the world through individual experience - self, and the inner world, and the unknown as the outer world. And somewhere in there is a horrible realization that even the inner world is unknowable.

There's a perverse comfort there, isn't there, in knowing that, amidst it all, even if we can’t quite see it, there is an all-encompassing order to things... even if it is, from our point of view, malevolent.

Cha: Yes, absolutely, I love that sort of thing. Like Lonnie said, that idea was one of the seeds that planted The Sickness and gave it almost a formal foundation of how we approach every bit of the story.