This column fulfills a promise. Last year, on the now-defunct Panelist site, I wrote three articles about my favorite DC comic book of recent years, Jonah Hex. (Although The Panelists are no more, you can read the articles here: one, two, three.) In my last Jonah Hex essay, I fretted about the impending cancellation of the comic and its reboot as All Star Western, a title designed to connect the Jonah Hex character—a disfigured, amoral bounty hunter blasting his way through a Leonesque western milieu—to the continuity of the broader DC Universe. As the publicity for the “New 52” crowed:

Even when Gotham City was just a one-horse town, crime was rampant–and things only get worse when bounty hunter Jonah Hex comes to town. Can Amadeus Arkham, a pioneer in criminal psychology, enlist Hex’s special brand of justice to help the Gotham Police Department track down a vicious serial killer? Featuring back-up stories starring DC’s other western heroes, All Star Western #1 will be written by the fan-favorite Jonah Hex team of Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti and illustrated by Moritat.

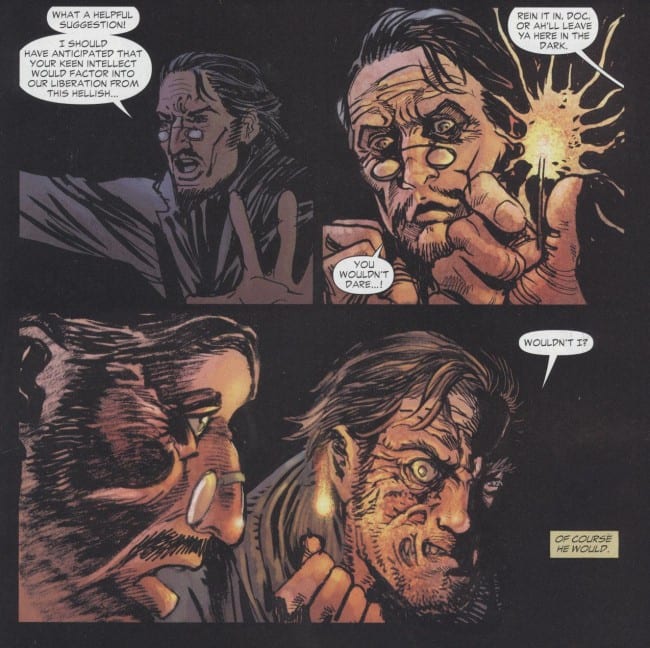

I found this PR troubling. As an admirer of Hex’s “done-in-one” aesthetic, how co-scripters Gray and Palmiotti usually told a complete, lean, and effective story in each individual issue of Hex, I was worried that allocating less pages for the Hex feature in All Star Western would lead to diffuse, rambling “to be continued” installments. I also couldn’t give a shit if Hex’s adventures connected with Batman continuity. So in my third Panelist Hex essay, I predicted that All Star Western would be a step—or several steps—backwards for Hex, Gray and Palmiotti, though to be fair, I promised to “review All Star Western after a few issues come out.” And here I am, ready to complain but taking no pleasure in “I told you so”s. I liked Jonah Hex, I strongly dislike All Star Western, and I want to explain my judgment by defining two key traits of the Western genre—its “between-two-worlds” central protagonist and allegorical plotting—and talking about how Gray and Palmiotti smartly folded these traits into Hex but abandoned them when they began their new title.

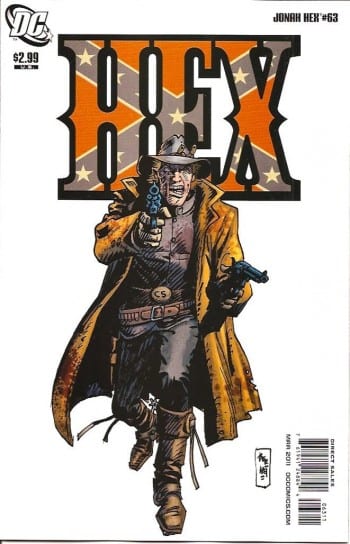

To keep my kvetching manageable (there are 70 issues of Gray and Palmiotti’s Hex), I’m going to zero in on Hex #63 (March 2011, art by Bernet) as a particularly strong distillation of the earlier series’ virtues. Let me begin, then, with a spoiler-filled summary of #63, although ideally you’d read the actual comic before plunging into my analysis.

Eyes

Hex #63, titled “Bury Me in Hell,” begins with Jonah on a mission to find a psychotic criminal named Loco, known for “murder, horse thieving, robbery” and sex crimes. (Loco is described as “a scalper with a real specific taste”: he’s cut off 47 scalps, all female.) A brief flashback reveals that Hex was hired by three townsmen, one of whom, Mr. Fassbender, was personally victimized by Loco.

The story then switches back to the present, as night falls, and as Hex meets up with Tavasi, an informant paid to locate Loco. Tavasi tells Hex that Loco is a day’s ride away, and then mentions that Loco has taken hostages: “Travelers from the west, families with young children…boys,” including a boy about five or six years old. At the mention of this young boy, Hex ignites into a vengeful rage, to which Tavasi responds, “You cannot save the boy, Hex. I saw his face. Loco has extinguished his soul.”

The oblique references to sexual abuse in both Mr. Fassbender’s dialogue (“He made me do things to him”) and the captive boy’s plight crystalize in another flashback, this one to Hex’s own childhood. We see young Jonah fishing with a friend named Aaron, when suddenly a well-dressed, ugly man bursts out of the bushes.

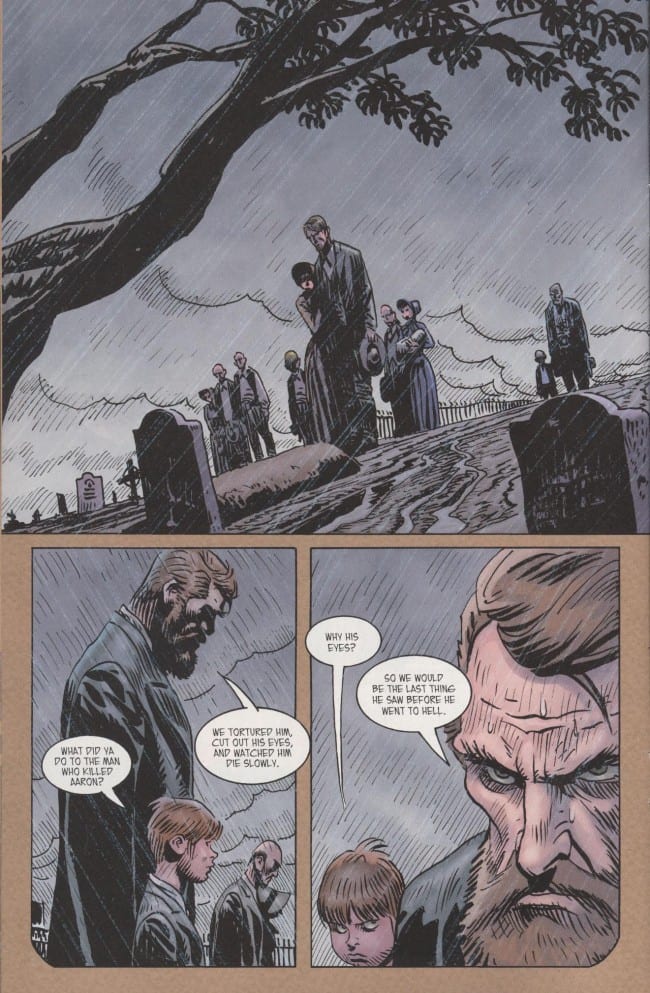

Jonah heads home, innocently leaving Aaron alone with the man. Later, Aaron’s father and a posse ride out to the Hex homestead, to tell the Hexes that Aaron is “dead, murdered in an unholy manner.” The well-dressed man is in the posse’s custody, and Jonah identifies him. During this scene, it is all but explicitly stated that Aaron was raped before he was killed. Jonah’s father Woodson Hex joins the posse, and later, at Aaron’s funeral, explains to his son the nature of frontier justice.

We then flip back to the present, where Hex realizes that Tavasi has set him up for an ambush from Loco. Hex dispatches Tavasi quickly—by pushing him onto a raging campfire—and the story then cuts to Loco and his gang hiding on a nearby rock, spying on Hex. Unaware that Hex knows about Tavasi’s betrayal (“The fire’s gone out, Loco” “So? He’s probably gone to bed”), Loco postpones his attack until morning, and he and the members of his gang eventually drift off to sleep.

At dawn, when Loco wakes up, he discovers that all his men have had their throats slit by Hex, and that his ankle is tethered to a wooden post. Loco is helpless, and Hex tells him “Y’re gonna take me to the boy.” After a grueling trek—especially for Loco, who is dragged behind Hex’s horse—Loco and Hex arrive at Loco’s camp, where Hex finds the remains of the captive boy. Because the scene is staged without a shot/reverse shot, we readers never see exactly what happened to the dead child, although sexual abuse is again strongly implied.

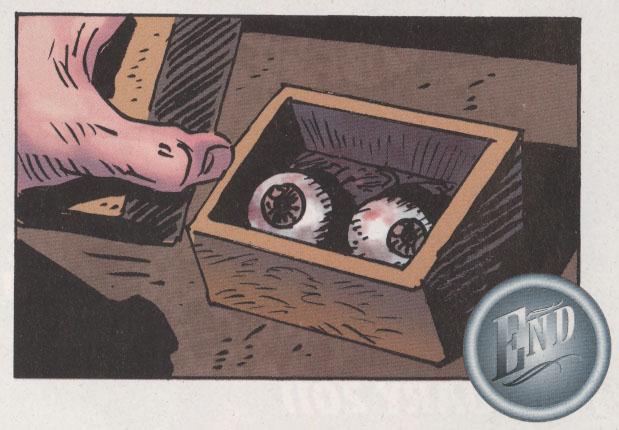

The scene ends with two panels: a close up on Hex, who vows that Loco will himself “be surprised how long it takes ta die,” and a tier-long panel of the cabins in Loco’s camp ablaze. On the final page, Hex returns to the townsmen, tells them that Loco is dead, refuses the bounty, and leaves a present:

Obsolescence

Clearly this grisly but well-crafted Hex story is a Western. You’ve got such stock characters as the bounty hunter, the frontier businessmen (typed by their clothes as Eastern, and thus vulnerable in the more brutal West), the settler family, and the evil savage (played here by a Latino instead of the typical “Indian”). We see situations—the manhunt, the posse, the campfire—we’ve seen in other Westerns, and the story unfolds in a desolate desert mise-en-scene, with Monument Valley buttes in several panels. In fact, the narrative hinges on the central character’s mastery of the Western environment. Just as John Wayne can shoot faster, ride harder and speak Comanche fluently, so too Hex realizes Tavasi’s lies, figures out Loco’s location, and silently kills the henchmen: the gunslinger as ubermensch, as superhero.

There’s more to the generic figure of the gunslinger, however, than his superhuman abilities. In his pioneering study Sixguns and Society: A Structuralist Study of the Western (1975), Will Wright argues that the narrative tropes of the genre comprise a “myth” that reflect the specific values of the cultures that produce Western movies and publish Western books and comics. As part of his mythological claim, Wright posits that the genre is built around a dialectical core, a tension between “wilderness” and “civilization.” In the tradition of structuralists like Claude Lévi-Strauss and Vladimir Propp, then, we can make a chart that places most of the aspects of Western narratives into one of these two categories, and create subsidiary dialectics:

Wilderness / Civilization

Gun Law / Court Law

Indians / Settlers

West / East

Horses / Wagons (or Cars)

“Dance Hall” Girl / Schoolmarm

…etc. Two ideas emerge as we look at this chart. First, it’s clear that many Western narratives explicitly enact in dramatic form the conflict between wilderness and civilization. Take, for instance, all three versions of 3:10 to Yuma (the Elmore Leonard short story [1953], the 1957 movie, and the 2007 remake), where farmer Dan Evans struggles to uphold culturally-sanctioned court law by sending criminal Ben Wade to trial, despite the frontier lawlessness (including the vigilante posse and the criminal gang) in his way. Second, the relationship between wilderness and civilization isn’t a balance: the history of the West (as both an actual time period and a fictional milieu) chronicles the rapid displacement of the wilderness by Eastern civilization. Gun duels are replaced by law courts, Native American tribes are driven off their lands by white settlers, and so on.

The gunslinger in many Western stories is a figure who straddles this wilderness / civilization dialectic. He is a master of wild skills like shooting, riding and tracking, but he also typically follows a civilized code of honor that brings him into conflict with lawless frontier thugs. This is true of both unambiguous white hats like Shane and more troubled characters like Deadwood’s Seth Bullock. Frequently, the gunslinger kills the bad guys in that most common of Western set pieces, the gun battle.

When the gunslinger eradicates lawlessness and allows civilization to overtake the west, however, he renders himself obsolete. All his talents—his horsecraft, his tracking, his shooting—are superfluous in the new world of judges, manners and marriages. Ethan Edwards brings his niece Debbie back to civilization, and creates a new family out of the ashes of his brother’s farm, but Ethan himself is too wild to settle down; in the last shot of The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), a cabin door closes, barring Ethan’s entry into the family. When Tom Doniphon shoots Liberty Valance (in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance [John Ford, 1962], he domesticates Shinbone, jumpstarts Ransom Stoddard’s law and political career, and reduces himself to an historical curio. Many of the greatest Westerns are elegies, songs for a dead way of life and the gunslingers that embodied those old ways. It doesn’t matter if this obsolescence happened in the real world. What’s important is that the Western functions as a one-size-fits-all allegory for actual situations of powerlessness, such as the humiliation of losing a job, and the ignominy of aging bodies. We are all of us gunslingers, waiting for the moment when our solidity melts into air.

When I talk about Western heroes and obsolescence in the film classes that I teach, I always show the opening 90 seconds of Sam Peckinpah’s magnificent Ride the High Country (1963). The film begins with a shot of a crowd on the streets of a Western town, as if waiting for a parade.

Then an elderly gunslinger (played by Joel McCrea, a leading man for Hitchcock and Preston Sturges, but also a veteran of dozens of TV and film Westerns) enters the town and sees the assembled crowd. He interprets the crowd’s cheers as a welcome, and perhaps as a delayed thank-you for his efforts in settling this Western town (and the West as a whole), and responds warmly.

When a police officer charges up and directs his horse off the road, however, the gunslinger realizes that he’s read the situation wrong, and something else is happening, something he doesn’t fathom. The cop asks the gunslinger, “Can’t you see you’re in the way?”—a question that applies to this specific situation, but also to the gunslinger’s status as an outmoded barrier to civilized progress.

The event that the crowd is primed to watch turns out to be a race among a camel and three horses. A banner stretched across the road advertises “The Phantom of the Desert! Takes on All Comers!” Horseback riding, previously one of the most essential Western talents, is now a circus act, a gimmick.

Immediately after the Phantom race, Peckinpah cuts to a long shot of the gunslinger as he’s almost hit by a car as he tries to cross the street. (The cop chimes in again: “Watch out, old timer!”) Maybe I’m fishing for symbols, but the car’s appearance, so soon after the debasement of horse riding skill, seems to exemplify once again a civilization willing to hit-and-run its past in its race towards a glorious future. In a later Peckinpah film, The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), a preacher says to his congregation that “The Devil seeks to destroy you with machines,” and the movie ends with Hogue dying from injuries sustained after he was hit by a car.

Admittedly, the first minute-and-a-half of Ride the High Country is a special case, a perfect example of the violence and obsolescence at the core of Peckinpah’s career and, more generally, the Western genre. (For more on this topic, I recommend one of the many fine books on Peckinpah, such as Stephen Prince's Savage Cinema [1998].) I’d argue, though, that these themes are also an integral part of Gray and Palmiotti’s Hex, as in the Loco revenge tale of #63. “Bury Me in Hell” begins with the three men (abused banker Fassbender, an unnamed sheriff, and a well-dressed spokesperson that might be the town’s mayor) upholding their own clean-handed civilized status by hiring Hex to be their surrogate in delivering savage justice to Loco. This he does, although Gray and Palmiotti clearly show that Hex isn’t driven by a sense of professional responsibility (he refuses to accept his bounty money) or a sense of kinship with his three employers. Rather, Hex’s motivations are personal, rooted in both his complicity in Aaron’s death and the eye-for-an-eye, torture-fueled frontier code he inherits from his father. Like so many other macho characters—Batman, Sam Spade, Kurosawa’s nameless samurai—in so many other genres, Hex is useful to civilization but stands apart from it, influenced by his own traumas and aims, but capable of unleashing uncivilized brutality that achieves civilized results.

Disappointment

Much of the nuance of Hex’s position between wilderness and civilization drains away in All Star Western. The first page of All Star #1 begins with an image of Gotham City in the 1880s, and with a series of captions that gesture towards the wilderness/civilization tension, as a yet-unidentified narrator muses about progress (“Civilization and time will continue their march…in spite of all that we may do”). Hex has come to Gotham, hired by the anonymous narrator, revealed to be proto-psychologist Amadeus Arkham, to help the Gotham police force investigate a series of brutal prostitute killings. For the first nine issues, Hex and Arkham team up to encounter various antagonists, including a secret society of affluent Gothamites called “The Lords of Crime,” a band of thugs who kidnap kids to work in the mines below Gotham, and even pulpy concoctions like giant bats and “the lost tribe of the Miagani.”

There are plenty of reasons why I consider All Star Western to be a lesser comic than Gray and Palmiotti’s earlier Hex series. For one, not enough Bernet, whom Darwyn Cooke called “the definitive Hex artist” of the contemporary run and who drew many of the best of the Gray-Palmiotti issues in his trademark scratchy, Kubert/Toth style. Bernet’s contributions to All Star Western, however, have been limited to a two-part, 16-page back-up in issues #2 and #3 featuring the supernatural Western character El Diablo. All Star’s primary artist, “Moritat,” isn’t terrible, but he’s not the hand-to-glove fit Bernet is to the Western genre. Moritat’s style--cartoony, with thick outlines, precise penwork and computer effects—is drastically different from Bernet’s ink-soaked brush.

The above splash is from All Star #9, a “Night of the Owls” crossover with various Batman titles in “The New 52” continuity. Personally, I can’t stand all the references to Owls and Arkham Asylum anachronistically shoved into Hex’s Western world—to paraphrase Tom Spurgeon, who the hell reads Western comic books for their connections to DC’s superhero “Universe”? Are fanboys so gullible and obsessed that they’ll buy a Western comic just because it takes place in 1880s Gotham City? Not me. I hate to see stories ruined by product placement.

My biggest problem with All Star Western, however, is Gray and Palmiotti’s recalibration of the Western’s civilization/wilderness dialectic. In Hex #63, Jonah Hex is untamed, yet still bound by a personal code of honor, and he’s also the character we connect with the most. Hex appears in almost every scene of the comic; we are given access to his intimate memories of Aaron’s death, and we share his desire to stop Loco. I don’t think our identification with Hex is total; he brutally slits the throats of Loco’s men, he follows his father’s example by torturing Loco (and cutting out his eyes), and at moments like these some readers might put up some psychic barriers between Hex and their own emotions and sensibilities. We do have a strong sense of Hex’s status as a loner, however, and over the course of Gray and Palmiotti’s original series we come to know Hex as a character whose allegiances to both wilderness and civilization are mercurial and complex. Hex emulates the elegiac, conflicted gunslingers in earlier Western fiction and film, and Hex benefits from its dialogue with these predecessors.

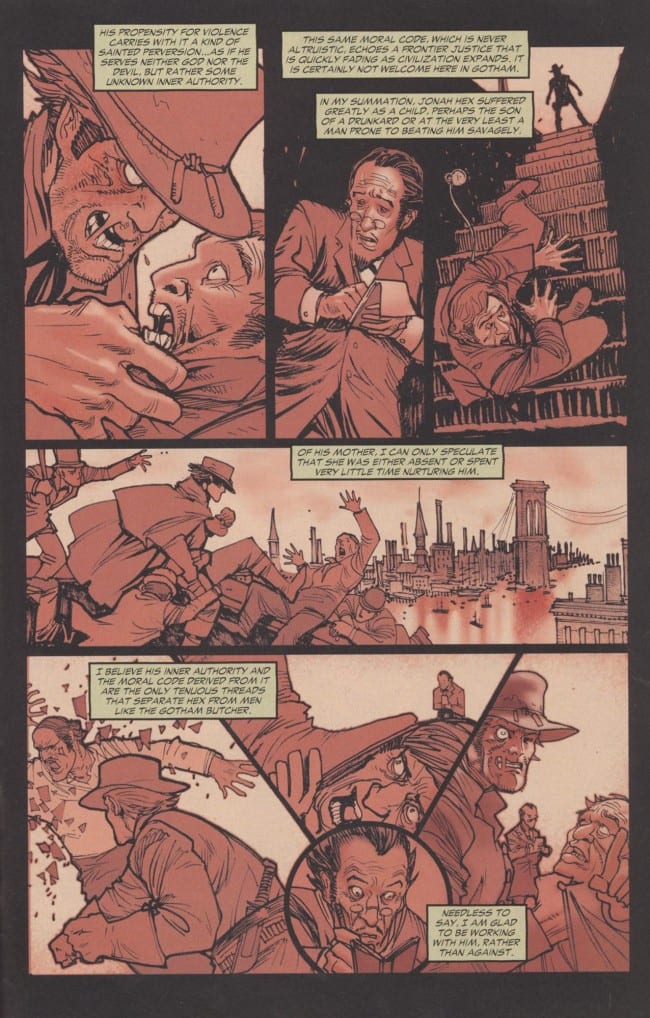

The storytelling in All Star Western, however, shifts Hex out of our central focus and identification, replacing him with Amadeus Arkham. In All Star, the caption boxes, the words on the pages not in word balloons, present Arkham’s first-person thoughts about characters and events. In a scene from the first issue, Arkham sits in his study, thinking about Hex’s pathologies, and his monologue touches on many of the themes (especially Hex’s “moral code” and “frontier justice”) that I’ve discussed here.

When I first read this page, I was impressed with Gray and Palmiotti’s familiarity with key tropes of the Western, but in retrospect I recognize the problems that would go on to plague All Star. For one, Arkham’s thoughts violate the “show, don’t tell” dictum—instead of inferring Hex’s morality from his actions, the reader is spoon-fed a big lump of exposition. Maybe Gray and Palmiotti felt like the first All Star Western should offer a thorough introduction to Hex for new readers, but I’m sure the two scenes of violence in the comic (an alleyway gunfight, a barroom brawl) are sufficient to define him as a troubled badass. Also, my main complaint is that Arkham provides the exposition throughout the series, since he’s an amazingly annoying character, a perpetually shocked milquetoast (despite his study of abnormal psychology), who is as out of place in a Hex series as Tony Randall would be co-starring with Burt Lancaster in Ulzana’s Raid (1972). Gray and Palmiotti try to make All Star Western the comic equivalent of a “buddy picture,” but the partnership between Hex the gunslinger and Arkham the fusspot never gels; they’re too different for drama and not exaggerated enough for humor.

Further: introducing Arkham into Hex’s world leads Gray and Palmiotti to split the Western dialectic between the two characters, with Hex defined exclusively as wild and Arkham as civilized. The pathos of the gunslinger in Western film and fiction depends upon his cognitive dissonance, his simultaneous connection with both West and East. By relocating the civilized part of Hex’s personality in Arkham, and by making Arkham the first-person narrator of most of the All Star issues, Gray and Palmiotti give us a less complex gunslinger, half a Hex.

Allegory

Movie Westerns usually have straight-forward, stripped-down plots. In Sixguns and Society, Will Wright lists several such plots, including (a.) the gunslinger who protects a town from malicious invaders (as in High Noon [Fred Zinnemann, 1952]), (b.) the gunslinger who cleans up a corrupt town (as in A Fistful of Dollars [Sergio Leone, 1964]), and (c.) the professional (or band of professionals) hired to complete a job (as in Unforgiven [Clint Eastwood, 1992] and The Magnificent Seven [John Sturges, 1960]). It seems to me, though, that the fable-like simplicity of most Westerns allows critics to pour complexity in them, to interpret certain Westerns as political and social allegories. In his book Seeing is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties (first edition 1983), Peter Biskind reads Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948)—a Mutiny on the Bounty on the Range narrative that pits paterfamilias John Wayne against young heartthrob Montgomery Clift—as a plea to redefine manhood in the post-WWII era away from machismo and towards greater kindness and sensitivity. More recently, Robert B. Pippin’s book Hollywood Westerns and American Myth (2010) considers numerous Westerns (Stagecoach [John Ford, 1939], Red River, The Lusty Men [Nicholas Ray, 1952], The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, etc.) as thinly-veiled meditations on how individuals come together to create and then live under a political system. As Pippin writes,

If we treat Westerns as a reflection on the possibility of modern, bourgeois domestic societies to sustain themselves, command allegiance and sacrifice, defend themselves from enemies, inspire admiration and loyalty (that is, to command and form the politically relevant passions in some successful way, to shape the “characters” distinctly needed for this form of life, then one surprising aspect of many Westerns (often criticized in the 1960s for their supposed chauvinism, patriarchy, celebration of violence, and so forth) is a profound doubt about the ability of modern societies (supposedly committed to peace and law) to do just that. (24)

Regardless of how you feel about Pippin’s thesis—that Westerns can be ambiguous and cynical about the functions and functioning of “modern societies”—the assumption informing Pippin’s work is that a Western story can mirror the ideological concerns of the time and place in which it was made.

Can a Western comic do the same? One obsessive theme of Gray and Palmiotti’s Hex was torture, a theme referenced on the very first page of #63, in a caption summarizing some of Hex’s earlier exploits:

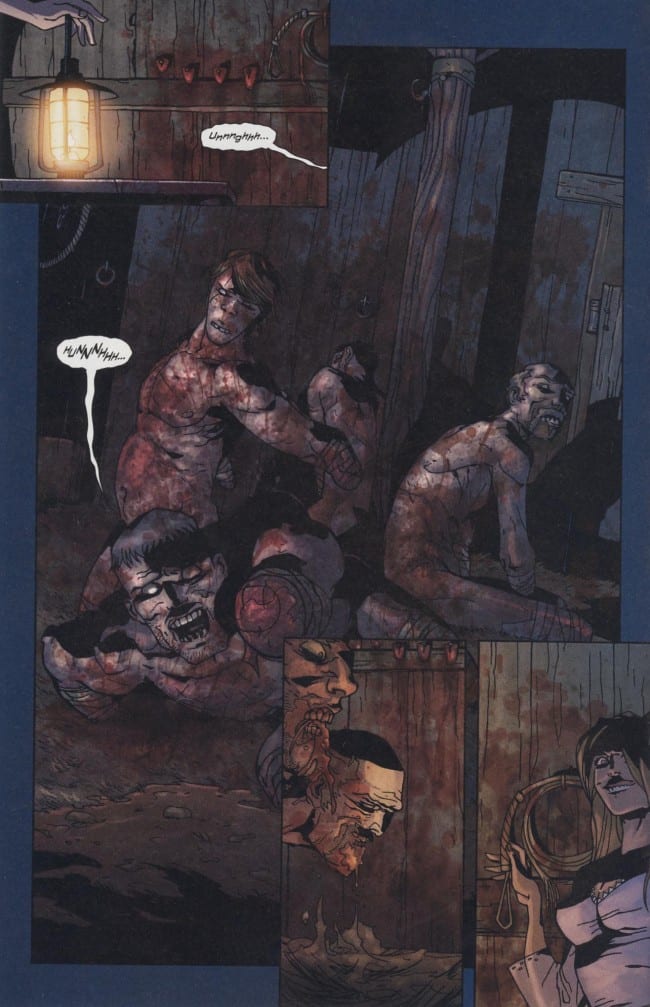

The characters listed in this caption were all torturers. Sawbones, for instance, was a sadistic surgeon who became a contract killer after the Civil War; in #40-41 (April-May 2009), Sawbones tortures Hex, after which Hex escapes and comes back for prolonged revenge. (Issue #41 ends with Hex holding up a knife, poised to begin his own regimen on Sawbones.) “Them sisters that cut men’s arms off an’ kept them in their barn like pigs” is a fair summary of issue #26 (February 2008), which is titled “Four Little Pigs: A Grindhouse Western” and which offers up the spectacle of mutilated men wallowing in a mud pit in a barn:

And then, of course, there are the numerous instances in #63: Woodson Hex’s description of how the posse tortured the pederast, Loco’s molestation of his young captive, and Hex’s climatic testing of Loco’s “endurance for cruelty.” Hex is a violent comic book, probably the most violent DC’s ever published.

I see the excess of cruelty in Hex as Gray and Palmiotti’s response, however incoherent and exploitative, to the United States’ culture of torture in the twenty-first century. Recall our contemporary history: Americans soldiers violated the Geneva Convention by torturing “enemy combatants” during an illegal foreign war, and the C.I.A. runs black site prisons that strip captives of due legal process and human dignity. (Of course, Americans knew about this torture before the 2004 presidential election, and we still voted W. back into office; on November 3, 2004, I wanted to renounce my citizenship—maybe I should’ve—and I’m still ashamed of our tacit endorsement of clandestine torture.) Meanwhile, in our culture industries, torture is in: note the popularity of Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2004), and the Saw and Hostel movies. We purport to be Happyland, but we’re Jack Kirby’s Happyland, where torture (fictional and otherwise) bubbles up despite our attempts to paper over the bloodstains.

I hope I’m not sounding prudish here. I actually like some violent fictional entertainments, even “torture porn” like the French film Martyrs (Pascal Laugier, 2008). Because torture is an integral part of the contemporary American zeitgeist, I’m grateful for texts that problematize an easy wallow in exploitative misery. Because Gray and Palmiotti structured most of their Hex stories with Hex as the central protagonist, as the object of our identification, his use of torture prompts uncomfortable questions: What happens when our heroes become torturers? Is torture a natural outgrowth of the Western’s ideology of regeneration through violence? Why is revenge so much goddamn fun? I can’t claim that all of Gray and Palmiotti’s depictions of torture serve philosophical purposes—it’s hard to justify the scene in #26 where the maimed male “pigs” get revenge on their female tormenters by biting them to death—but frequently their scenes of cruelty unsettle me in ways that go beyond mere sensationalism. Much of the torture in Hex #63 is unseen by the reader (just outside the panel borders, and thus not a convenient dose of pain and gore) and emphasizes some of the similarities between Hex and Loco: both are torturers, and the main difference between them is who they brutalize.

Needless to say, there is very little torture, and no study of the ramifications of torture, in All Star Western. Instead of the tight, violent, terse morality plays of the Hex series, All Star substitutes a “New 52” blockbuster aesthetic, with multiple single- and double-page splashes, multi-issue continued stories, pulp adventure plotting, and elaborate tie-ins with the Bat Cave and other elements of Bat-continuity. In the second issue, Gotham’s police chief is kidnapped and strapped to a slab, but the scene is played exclusively for thrills, as Hex and Arkham charge in to save the day. It’s playful, and palatable to fans of superhero comics, but I miss how Gray and Palmiotti’s obsession with torture gave Hex a vital engagement with pressing ideological issues outside the comic itself. In contrast, All Star Western seems sealed in its own generic world, self-contained and much less interesting as a result.

My complaint here is that Hex’s idiosyncratic qualities, including the series’ ambiguous, Western-style protagonist, and its focus on the ethics of torture, have been paved over by All Star Western’s pandering to the market. An unexpectedly lively comic book—and the only contemporary Big Two comic that dove into some deep currents of the Western genre—is gone, replaced by a sleek and soulless New 52 machine. And to repeat what the preacher in Peckinpah’s Ballad of Cable Hogue says: “The Devil seeks to destroy you with machines.”