Interview conducted by telephone on March 8, 2016, and this text edited from that conversation.

Interview conducted by telephone on March 8, 2016, and this text edited from that conversation.

Todd Hignite: I’d love to start by hearing about your process and approach to such a long-term project. It’s obviously unique for you in terms of scope, but can you speak to how you see your work on Patience within the trajectory of your career?

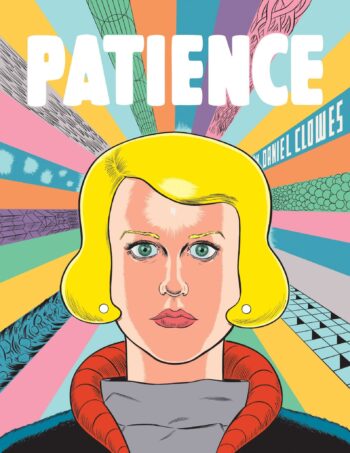

Daniel Clowes: Well, when I began, I thought it was going to be a lot more streamlined, I guess—I have an early outline where I guessed that the whole thing would be under a hundred pages, so adding that many pages shows quite a shift in what I was intending. You know, most of my work, especially the last three or four things, The Death Ray, Ice Haven, and Wilson, are all about paring everything down to the bare minimum in a way, where each part of the story is boiled down to a little essential moment, and then those are pieced together to create a longer narrative. I felt like I was moving in that direction for a long time and Wilson was kind of a culmination of that, where there’s no exposition at all, it’s just the heightened moments of this character’s story—and after finishing that I kind of had the desire to do the opposite, which was to give myself as much space as I wanted, so if a single image felt like it was big enough to cover two entire pages, I could feel free to do that, and have a rhythm within the story where that made sense. So, it was in many ways a very different experience. It’s funny because in some ways this is probably the most readable, and worked out story, plot-wise, that I’ve ever done, but it also felt very experimental to me, because it was so different from the way I’d been normally working.

TH: Randomness, order, and fate are themes that you’ve explored overtly and as subtext in your work—and these big ideas in many ways guide the narrative of Patience—were such concepts the germ of the story, or does that come from the characters of Patience and Jack?

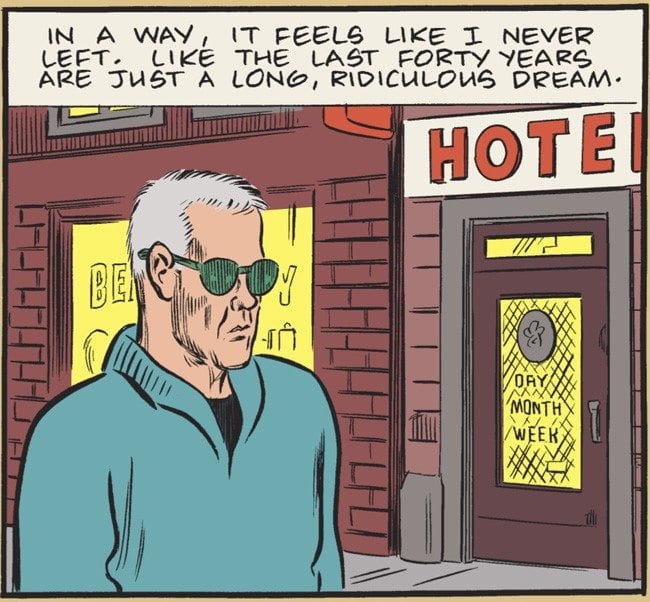

DC: Originally, the story came from the older Jack character—he was the first character in the story—and then I started to think that he would be more interesting from the viewpoint of the Patience character. So then I started to think about her as someone who’s sort of baffled by this creature, and she really came to life and became the most interesting character to me. So they were vying for power in the story and I tried to give them a certain amount of equality within the narrative, which is always difficult. You usually have to weight it one way or the other.

TH: That dynamic was very interesting to me—Jack leads the narrative, but there’s a very religious aspect to the pending birth of the child, and an optimism and spiritual aspect to Patience, with all of these crazy male characters constantly crashing into each other around her.

DC: (laughter) That’s right—but I certainly never set out with themes or work out what I’m trying to say, or what I’m trying to explore in a broad sense, rather I try to think of scenarios and situations that I know resonate with me on some deeper level. Something I think about a lot. You know, that’s generally the rule of thumb, if something is part of my daily endless churning cycle of thoughts then it’s something worth putting into the comic because I know it’ll hold my interest. I always go back to Krazy Kat, where Herriman basically did the same joke every day for the entire run of the strip, but there was something about that which was endlessly compelling—so I’m always looking for that in a long-form version.

TH: We see versions of Patience keep showing up in Jack’s mom, the woman in the 1980s bar, the 2029 prostitute—their appearances speak to her as an enduring image or character.

DC: Yeah, those are examples of decisions you make in the moment, that resonate in the story.

TH: The time-travel narrative immediately invites the reader to project their own personal history into the narrative, that notion of what one would change if it were possible is one of the major driving forces behind the story.

DC: Yeah, it’s funny because as a kid I thought about that all the time, every day at school something would come up, “If only I wouldn’t have picked my nose in front of that girl in science class!” Those little minor events that constantly go through your consciousness you wish you could eradicate are a big part of it. But when you reach my age you have such a huge accumulation of those, you stop worrying about it. There’s not a single thing I could personally pick to go back and redo. There are of course many things that I regret, but it would take a lot of time traveling to fix them all (laughter).

But part of the process of doing the book was sort of embracing all of those events that make you exactly what you are in this moment, you know, and that’s something I was thinking a lot about with the book. You have these two versions of Jack, the main character, and one of them is an innocent young man, and the other is the exact opposite of that in many ways. There are obviously many versions of how he could have ended up, and you see this kind of flowchart of decisions and events that turn you from this one person into another person who’s almost unrecognizable.

TH: It’s heartbreaking in the story how difficult lives are, specifically Patience’s—the residents of White Oak are frightening on many levels, particularly their child rearing—

DC: (laughter)

TH: —as always in your work, the incredible observational detail immediately sets it apart, and not to get too personal, but I’m sure the experience of being a father played into the narrative.

DC: Oh yeah. Well, you start to think back on your own childhood and about all the horrible parenting decisions my parents made—especially growing up in the ’70s, that was sort of the low point of parenting (laughter), and so everybody I know around a certain age has such awful memories about their parents’ carelessness and self-obsession, so I’m very aware as a parent of not doing what was done during that era—so I’m sort of hyper aware of that when I see it out in the modern world. It’s one of those things where you really can’t believe that certain people are allowed to raise kids (laughter) when they’re completely inept in every other phase of their lives, it’s shocking to see.

TH: With Jack as a character, there’s this almost dream of omniscience running throughout, he’s the author of the story, ultimately directing events, but on another level, is he something of a stand-in for you, revisiting your earlier work? I got a real shock at a certain point and undoubtedly started reading too much into this, imagining clues and references in specific panels, backgrounds, locations, perhaps aged versions of previous characters, and dialogue…

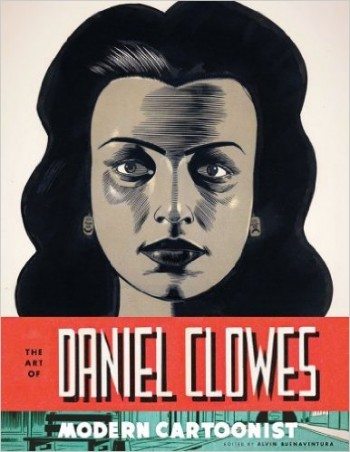

DC: (laughter) I don’t know that that’s necessarily the case, but I can say that I was definitely very influenced in the story by my own work because I had spent so much time putting together the Modern Cartoonist art show and monograph, and then that was followed immediately by compiling The Complete Eightball, so I was very much in the world of my own comics in a way that I’ve never been. Normally, I try to not look at my own comics at all, and I try to be influenced by things outside of not only my own work, but outside of comics—I try to find unfamiliar things to be influenced by in each book, and in this case I was really kind of immersing myself in my own work, using myself as a reference in the way that in an earlier book I might have used Charles Schulz or Johnny Craig, or somebody like that (laughter). It was kind of an odd experience and I did find myself creating little glimmers of recognition with old characters and giving little nods to previous ways of working, maybe.

TH: A return to Chicago in the year 1985 seemed poignant.

DC: Yeah, that was the year that I began, so…

TH: Your career as a cartoonist.

DC: Yeah… (pause).

TH: You’ve explored numerous genres in your work, playing with conventions and tropes—not as a formal exercise, but in service of telling an emotionally impactful story—but what does genre mean to you when you’re using it in a book?

DC: You know, I find that I have this sort of perverse idea that I’ll do my own version of a superhero story or a science-fiction story—I think normally that would involve someone rereading all the time-travel science fiction to understand what that genre was all about, and either going along with that or subverting it in some way, but the way I do it is to start with no knowledge of it at all and imagine that I’m an alien coming to earth and I’ve been told about time-travel genre science fiction, and then just trying to reimagine that entirely on my own. So the whole background I have is the most generic—I’ve seen The Terminator and Back to the Future, the original Time Machine from 1960 with Rod Taylor—and I can’t even definitively say that I’ve read a time travel story. And I’m not interested at all in the physics of it or in the mind-fuck aspects of it, it’s all just a great thing to use in a story. It’s a great device and it has sort of a primal quality in that everyone’s thought about it, and everyone has their own ideas of how it would be used. I wanted the main character to be somebody who never would have thought about it except as a desperate last resort.

TH: If I think about the best genre writing, it’s a means to another end, it’s a set of structures or rules that get you to arrive at the real point in an interesting way—I’m thinking of someone like David Goodis, who’d use a heist narrative, or whatever—

DC: Which wouldn’t work out, or make sense, but would show the bleak despair of his characters. Yeah, you know I was sort of high-mindedly thinking of movies like Solaris or Alphaville, things like that, which are not in any way like this story, but are things that purport to be science fiction but are using it for very different means and ends.

TH: Patience is very much a “comic book” as opposed to a comic that makes reference to newspaper strips, and it has the structural diversity you’d expect, big double-page splashes, and the color seems to me really important to the pacing—can you speak to how those formal elements work with the narrative?

DC: It was a thought when I was beginning—certainly the last books I mentioned, I’d been mostly looking at newspaper strips—it was all of a sudden an era at that time, not only where there were a lot of reprint books on strips you could never see before, but for me it was the era of eBay and being able to buy huge bulk collections of newspaper strips, so I’d have four feet of clipped Sundays and dailies sitting in my studio. I was so immersed in that world for the first time that it felt really exciting for those books of mine, and when I was done with Wilson, I really felt like I was done with that. I really had this desire to go back to regular old comic books. So the way the book looks has a lot a lot to do with thinking of the two-page spreads in an open comic book. The way I intend it to be read as a book, you’re looking at the two pages at once, your eye is taking that all in. So I drew the entire book as two-page spreads and conceived them as units in the story as well as these sort of singular visual spaces.

When I began, the influences I was thinking of were Ditko’s Dr. Strange, and also Mr. A, where he draws those crazy landscapes with Mr. A standing in some behind-the-scenes reality where giant words like “Lies” and “Deceit” are attacking him (both laughter). I mean there’s something really threatening and primal about those drawings to me. And then Kirby’s big, expansive, cosmic-consciousness thing. But when I was trying to find the perfect reference for those to inspire me, I could never find them—they were all in my head. I always imagine Kirby having all of these images of like “going into the pure light,” the kinds of things I was trying to draw, but it’s all machinery—very different from the kinds of things I was looking for. So as with many things I do, my influences are the way I imagine something that doesn’t actually exist.

TH: My assumption is that there would be great interest in making a film of any book you do now. Since you’ve been immersed in that world for periods, is it inevitable that the cinematic language is in the back of your mind—this would be sort of unique to you as a cartoonist who has straddled both worlds.

DC: I don’t ever think about that when I work on a book—it’s just sort of a trick I play on myself, I just assume that a movie is not going to happen—that it will exist only as a comic. But of course everyone who sees this one, sees that it leans more heavily on the visual end of things, so I think there is a lot of curiosity about that aspect of it, but it’s not anything I’ve pursued at this point.

TH: Do you mean visually that it’s quote-unquote cinematic, or…?

DC: Or that it’s something a director might look at and say “This is the kind of thing I can see up on a screen.”

TH: But to your point, it does read very much as a comic book—to use an example, the silhouettes at the outset are a really effective introduction to the story and themes that probably works best specifically in comics.

DC: Yeah, there are some images that would work on film, but a lot of it is that the language of comics allows you to be, I don’t know, garish and extravagant in a way that doesn’t read that way—but if they were filmed it would look mannered and over the top.

TH: In terms of your experience in that world, does it really come down to economy and editing, skills that are applicable to comics?

DC: Because you have such an intimate interaction with the people you’re working with in that environment, a real honesty and bluntness comes through—you can’t afford to be polite and say “Oh, that’s great, let’s just film it as it is.” Everything is brutally picked over—some of that is not valuable, some of it is just people trying to get their opinions across and that becomes sort of a power play, but a lot of it is a way you learn—there are many things I think are clear that I’m trying to get across—a subtle, clear, universal point—that aren’t coming across at all. You talk to very smart people who are reading the stuff and they have no idea what you’re actually trying to say. And that’s really illuminating for me (laughter). So I sort of feel like in the comics, I leave all that stuff in, in the hopes that there are eight people in the world who it’ll come across to. But I also don’t want those things to be off-putting to the rest of the world, so I try to make a book work on some level for everybody and maybe on a deeper level for those few who are really in tune with it. But on a film that’ll never make it, unless you’re writing, directing, and producing your own thing and don’t have a lot of outside influence.

TH: I’ll ask you a big question: what affects you the most artistically? Or maybe for you, when you’re working on a comic, is there a desired artistic effect—is it some kind of ineffable emotional response?

DC: Do you mean what am I trying to get across?

TH: Yeah, we talk about these very specific elements of your work or art in general, but at the end of the day what’s the most important thing for you?

DC: You know, I try not to do anything that’s not deeply felt. For all the characters and situations, I have to kind of be living in the story. Before I ever get started, I have to have thought about the story so much that I know the characters completely before ever drawing them for the first time. And I just have to hope that that in some way comes across. That I’m not just filling up pages and trying to get through the story, to do an assignment, or anything like that, but that I’m trying to really get across something that’s deeply emotional and powerful to me, and hope that it all means something to somebody else.

TH: The art that means the most to you, that’s also what you take away from it?

DC: I think I have a pretty good sense of that, when an artist is doing something that comes from that place, rather than sort of trying to please their fans or whatever…

TH: Or fill in the expected blanks somehow…

DC: Right.

![clowesthumb[1]](https://the-comics-journal.sfo3.digitaloceanspaces.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/clowesthumb1.jpg) TH: I want to ask you about the evolution of your drawing style—the early issues of Eightball were really dense and angular, with a lot of hatching that is sometimes grotesque and jarring—that style is sort of the gestalt of that early work.

TH: I want to ask you about the evolution of your drawing style—the early issues of Eightball were really dense and angular, with a lot of hatching that is sometimes grotesque and jarring—that style is sort of the gestalt of that early work.

DC: Yes, a signature—

TH: But gradually a lot of that was drained away toward a more simplified style, the comics became less about foregrounding art style and more about fusing all the elements together in terms of storytelling—can you talk about that at all?

DC: Certainly I’m now intimately conversant with that, having gone through the work for The Complete Eightball—I can see in a lot of the early work, I was using the skills I had, a slick-ish inking style, I knew a lot of comic book techniques, I was using those to obfuscate some of my deficiencies, really my drawing—there’s kind of an odd push and pull between the crudeness of some of the artwork and the overwhelming work put into each panel. I think it has a certain draw, for sure, I can look at that stuff now and it feels very indelible. It doesn’t feel like you’re looking at a John Romita comic, where you’d see the same face perfectly drawn over and over and over, and that has a very different effect than if you’re looking at my early comics that have these kind of bizarre, angular, as you say, images that feel—I don’t know, they do feel indelible, as I say, in a certain way now. I can’t imagine them being reconceived. The thought of redrawing them would only damage them.

TH: Do you think now more that the best comics are those in which you can’t separate elements in this way?

DC: I don’t know—I’m not one to try to overanalyze why comics work or don’t. I always feel that’s like people who listen to comedians and then take apart their jokes to find out why they work—it’s such a joyless endeavor. Something like the strip Barnaby is such a repudiation of any rule I would make about comics (both laughter). It’s got everything wrong with it and yet it works perfectly.

TH: You’ve always seemed to me, even when you were in your late 20s, to be sort of an elder statesman of comics, the smartest guy in the room, and I know how crucial your support and encouragement has been to younger cartoonists—I’ve never heard you talk about this—did you ever have sort of a mentor once your older brother left home?

DC: No—no, I didn’t. And I often think about what a great shortcut that would have been (laughter). But there’s also sort of the beauty of figuring it out for yourself. You have to have a certain dementia to keep at it, when you’re just constantly not living up to what you’re trying to do. I was just visiting Charles Burns in Philadelphia and he showed me some comics he’d done in high school that were incredible, better than just about anyone working professionally today. He just had it right out of the gate. The inking doesn’t really look like his current inking, but it was incredibly accomplished and just beautiful, beautiful stuff. And I surely didn’t have that to keep me going (laughter). It was really just a demented mission to find my way.

TH: The culture is so different now—and a book like this, your work, has such a different place in it—but do you look back on the comics world of the early ’90s fondly? It was such a big event in my mind for a new issue of the comic to come out then.

DC: (laughter) I try not to over glamourize it, because in many ways it was just the most dispiriting, small-time world (both laughter) that just made you feel awful all the time. The thought of trying to explain what you were doing to anybody outside of that world was hopeless, they would look at you like you were telling them you were saving your own earwax or something—“Why in the world would you do that?!” But of course I did like the smallness of the world in many ways—just on this book tour last week I met a few people who said, “I used to write you letters in the Eightball days,” and when they told me their names I knew who they were immediately. We knew everybody—me, Jaime, Gilbert, and all those guys, would always talk—“Hey, do you get letters from this guy?” It was sort of a one to one relationship.

TH: I have a really clear memory of picking up the first issue of Eightball and being very shocked by the subheading on the inside front cover—

DC: (laughter)

TH: —what does “An Orgy of Spite, Vengeance, Hopelessness, Despair and Sexual Perversion” bring back to you now?

DC: It’s funny, I remember just needing to fill space. I liked how in old men’s adventure magazines they would include some guiding principle for the manly men among us, and it always seemed kind of aggressive and over-the-top, so I thought I was going to do one of my own—but I remember not thinking about it very hard, but just writing the first thing that popped into my head, and later thinking “That was a weird manifesto to try and live up to!” (both laughter)

TH: Those early issues railed against the phoniness and shallowness of mainstream consumer culture as contrasted with your personal obsessions and interests—positioning you as something of a spokesperson—unwitting, probably—for a larger culture of disillusionment. Is your rejection of mainstream culture so strident these days?

DC: It’s truly a losing battle (laughter). I mean, our culture has gotten so fragmented since then. Really at that time, there was the huge monolith of mainstream culture and then there were these little fringes that had no impact at all on anything. You really had to go through so many hoops to buy even my comics, which would have been thought of as sort of a big success, but if it was even a little more fringy, like personal zines people were doing or small, independent films, it was almost impossible. You really had to be an insider in this hipster world to know how to find stuff like that. Nowadays, everybody’s in some weird niche that none of us can even comprehend. I remember thinking at one point that if the population increases a certain percentage, and the readers for our kind of comics grow with the population, then we could have our own kind of little niche support out of that tiny fragment of society that would keep us going. And that’s almost actually happened.

TH: Although there’s also still plenty of horrific stuff to react against.

DC: It’s funny, back when we began, we always thought “Our comics are the real mainstream comics, they’re about day to day events, and they’re for adults, and superhero comics are really of no interest to anybody else, only for the fanboys”—and then the whole world kind of repudiated that really loudly (laughter). I talk to parents of my son’s friends and they couldn’t be more excited to go see The Avengers, so I truly wonder what’s happened to us.

TH: You’ve mentioned the retrospective exhibition and monograph in conjunction with working on Patience—how did that museum world affect you, and what does the art world acceptance of comic art, and specifically your work, mean to you?

DC: It was interesting because there are so many protocols and mores of the museum and art worlds that don’t apply to comics, even in the nomenclature that they use to describe the artwork—they call pages “panels,” and it got really confusing and I kept trying to reeducate them, so things like that were really funny and made you realize that it’s another world. They would do these really careful condition reports on all the artwork, noting that something had an ink stain on the corner—yeah, that’s kind of how it is (laughter). We’re not really working on these with cotton gloves trying to keep them in pristine condition; these are just the artifacts of the process. If the book had ink stains, that would be bad. So it was sort of a funny meeting of these two, what you would think would be connected worlds, but in many ways, they were not at all.

I went into it, not thinking I particularly wanted to do it—it was one of those things that I agreed to in a weak moment then kind of regretted it, but then once the shows actually happened, I found that it was really kind of profound to walk into a room with all of my work on the wall. I couldn’t accept it as myself, really. I kept trying to think of myself as the greatest collector of Daniel Clowes artwork—I took more pride in looking at the little cards that listed “Collection of Daniel Clowes” than the artwork itself. Which I guess says more about me than I want to admit, but to see the artwork on the wall and to give it this kind of extra charge was a really good thing. You’d see people who had read the books for years and knew the work intimately who would see the page on the wall and stop and say “Oh my god”—they were taken aback by seeing the real thing, to see it sort of demystified. On the other hand, there were of course a lot of people who had never known the work or heard of me at all, and you’d see them looking at the artwork and getting lost in the narrative, and then wander over and pick up the book—so it worked in those two separate ways in a really interesting way.

And I’ve always liked to look at original art—there’s always something that’s compelling to me, and I own a lot of artwork by my favorite artists—a lot of it is to sit there knowing that you’re sitting at the same distance from the art as when that artist drew it, that they were all over the page; there’s some connection there that’s really meaningful. Of course, I don’t really have experience with my own artwork (laughter). Though, sometimes I will dig out an old page and it’ll pop in my head what I was listening to on the radio when I drew it. There are these mnemonic things with the artwork that don’t exist with the printed art that can be really uncanny.

TH: After a big project like Patience, is there a lull or were you right back to work?

DC: I was hoping for a lull, but for the last few books I’ve finished, I’ve had something I had to do right away, so I’m pretty sure I haven’t had a break at all for over ten years, I’d say. Maybe at the beginning of Patience I could consider that a little break, but I was also working pretty hard to get something together. So I really wanted to take like a month off, but after two days I started to feel so useless. What do people do? And I kind of hopped right back into it—right now I’m on this book tour so I can’t really do anything, it’s too distracting, but before and after that, I’m starting on a new book; I have something very vaguely in mind. But really, all I want to do right now is comics. It sort of feels like, “What could be better than that?”

Todd Hignite was founding editor of the magazine Comic Art, is the author of The Art of Jaime Hernandez/The Secrets of Life and Death, and In the Studio: Visits with Contemporary Cartoonists, and curated the museum retrospective R. Crumb's Underground. He first interviewed Daniel Clowes 25 years ago.