Walt Kelly became a resident of Connecticut in 1915 at the age of two. Born in Philadelphia, he arrived in Bridgeport with “father, mother, sister and sixteen teeth, all my own.” Until then the most illustrious citizen of the town had been P.T. Barnum, whose legend would have an influence on Kelly as he made his way to young manhood.

Walt Kelly became a resident of Connecticut in 1915 at the age of two. Born in Philadelphia, he arrived in Bridgeport with “father, mother, sister and sixteen teeth, all my own.” Until then the most illustrious citizen of the town had been P.T. Barnum, whose legend would have an influence on Kelly as he made his way to young manhood.

The ambition to be a cartoonist had hit him early on and he began drawing for the Warren G. Harding High School newspaper and its yearbook. At the same time Kelly was writing a column of high school news for the Bridgeport News and drew a comic strip for them about that that flamboyant showman Barnum.

In 1930, fresh out of high school he was at the Post working at, according to comics historian Richard Marschall, “almost everything in the art and editorial departments, learning his trade and somehow, by osmosis, a transfusion of printers' ink for the blood in his veins." In the middle Thirties, he managed to sell some stuff to Major Malcolm Wheeler Nicholson’s fledgling and low- or non-paying comic book. For New Comics he drew a few center spreads based on such literary works as Gulliver’s Travels. One of the Major’s early rivals, Funny Pages, bought two samples of Canonball Jones about a fellow who is trying to go back to nature. Not especially funny or well-drawn, these were most likely samples of an unsold comic strip.

Came 1936 and Kelly headed to Southern California, where it never rained or snowed, to try his luck at animation for Walt Disney Productions. At that time, as Marschall has pointed out, “the studio was hiring thousands of artists and providing classes in various aspects of cartooning and animation.” They were preparing to expand into full-length, full-color cartoon films.

Years later Kelly expressed some doubts on the value of the classes he had attended, but he was considerably tipsy on that occasion and his negative side took hold of him. His thoughts on that topic emerged at the November 1969 National Cartoonists Society annual banquet, in an interview by Gil Kane with a large group of his fellow cartoonists in the audience. After getting a few sullen and whimsical answers, Kane stopped in the middle of his fourth question and said, “This isn’t going to work.” But Kelly replied, “You said you has a hell of a lot of good questions to ask me and I want to hear one of them.” Reluctantly Kane continued and asked, “I was wondering if there was some turning point, something that influenced your very substantial attention to craft. No kidding, now.”

Kelly’s response was ambivalent. “Hunger. I mean, here you were starving to death, working for Disney. Disney was a good training school in that the people he had working for him the best cartoonists that I have ever seen in a group….[But] even out there, not all of them were good. Some of them were terrible.”

Kelly once said that he and Disney “and 1500 other worthies turned out” to work on Snow White, Fantasia, Dumbo, and The Reluctant Dragon. After the screening of that latter film, he “quietly disappeared and next showed up on the Mojave Desert trudging East.” Kelly has been criticized by many of those 1500 worthies for crossing the picket line during the massive studio strike of 1941, in which the majority of animators and artists were asking for the right to unionize.

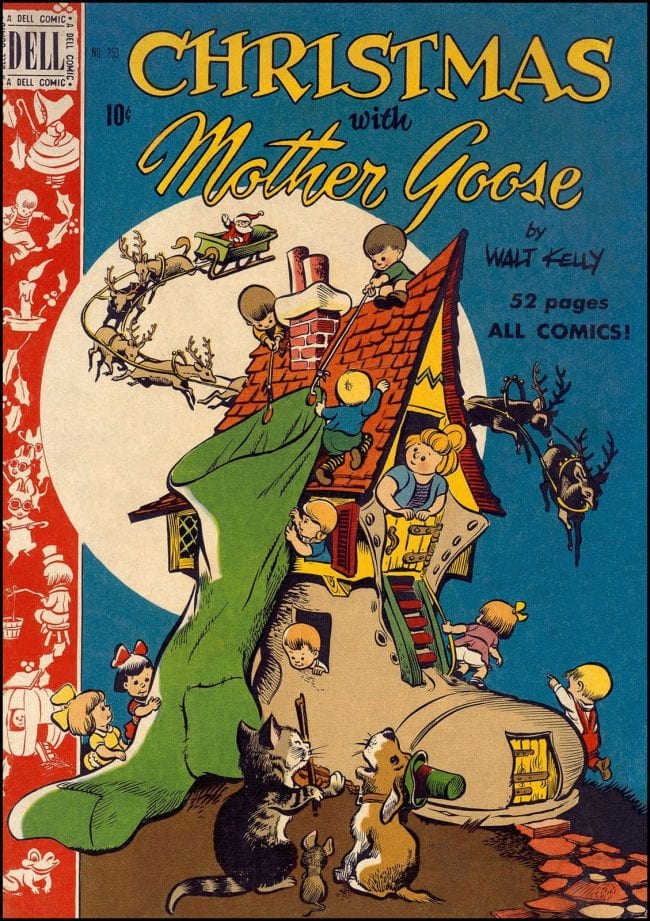

He may have felt that working conditions would be more peaceful elsewhere. The Disney art classes had helped Kelly to master the drawing of funny animals (despite what he’d said later). The next important influence on him and his career came from Oskar Lebeck, a New York City editor who was also a writer and a cartoonist and a man who had left Germany in the early '30s. Lebeck had been involved with The Mickey Mouse Magazine, handling editing and drawing a two page comic strip titled Peter the Farm Detective. He was the chief editor of the Whitman/Dell group of comic magazines that included Popular Comics, Super Comics, and Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories. And he was in the process of launching several new titles: Fairy Tale Parade, Animal Comics, and Our Gang.

Back again in Connecticut, Kelly and his wife were living in the vicinity of Bridgeport. Still on good terms with Walt Disney, and disdainful of the majority of his colleagues who’d gone on strike, he’d asked his former boss to help him find work in the New York area. Disney complied and dictated some letters to the higher ups at Whitman/Dell. He described Kelly as “having a complete understanding of all our characters.” Michael Barrier, in his recent book Funnybooks, speculated that “it was undoubtedly through [one of these letters] that Kelly met Oskar Lebeck and began drawing comic books for him.”

Lebeck recognized that Kelly was going to be a star and he used his work in just about every comic book he was involved with. For Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies Kelly first did Kandi the Cave Kid, a basically cute feature. Later he took over Pat, Patsy & Pete, about two kids and a talking penguin. It had been created by former Disney man Win Smith, who had drawn the Mickey Mouse comic strip just before Floyd Gottfredson took it over. In the six episodes that he drew and wrote, Kelly moved away from what his predecessors had done and converted it into a series of comedies that looked like storyboards for raucous two-reel movies comedies. Kelly also did many handsome covers for the Disney comic books, proving that he did have “a complete understanding” of all the Disney cartoon characters. In addition, he drew the comic books that were adaptations of the studio’s two “good neighbor movies”---Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros.

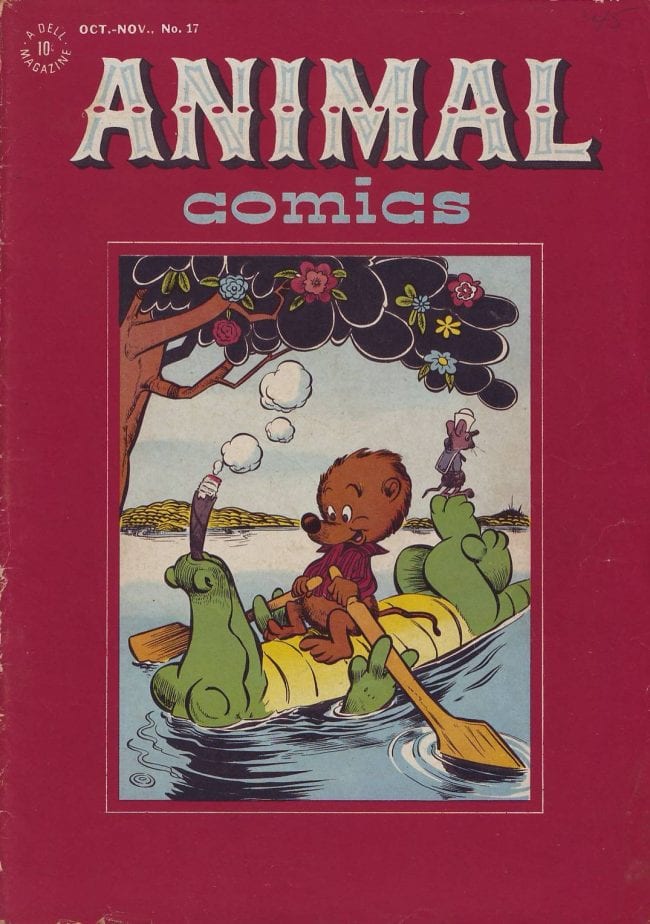

The feature that would bring Walt Kelly fame & fortune had its humble beginning in Lebeck’s Animal Comics in 1942. The intended leading character of the comic book was that venerable and much-loved rabbit gentleman Uncle Wiggly. Created by Howard Garris some decades earlier in a daily text newspaper series with one illustration by Lang Campbell, he had graduated into children’s books and newspaper strips. Kelly’s Pogo and his Okefenokee associates gradually pushed him into a second banana position.

At the start even Kelly didn’t quite realize his possum’s potential and figured that Albert the Alligator would be the leading man. Initially Pogo was just a “spear carrier,” as Kelly pointed out, handicapped “because he looked just like a possum. As time went on, this condition was remedied and Pogo took on a lead role.” The new feature appeared under a number of different titles in its first Animal days: Bumbazine and the Singing Alligator, Albert and the Noah Count Ark, etc. before settling down as Albert and Pogo. Bumbazine was a small realistically drawn African-American boy who shared the swamp with the animals and, in the manner of Christopher Robin, was able to talk to them and they to him. As the feature progressed Bumbazine and the other swamp critters abandoned conventional speech for a patois that was part Southern and part Li’l Abner.

At the start even Kelly didn’t quite realize his possum’s potential and figured that Albert the Alligator would be the leading man. Initially Pogo was just a “spear carrier,” as Kelly pointed out, handicapped “because he looked just like a possum. As time went on, this condition was remedied and Pogo took on a lead role.” The new feature appeared under a number of different titles in its first Animal days: Bumbazine and the Singing Alligator, Albert and the Noah Count Ark, etc. before settling down as Albert and Pogo. Bumbazine was a small realistically drawn African-American boy who shared the swamp with the animals and, in the manner of Christopher Robin, was able to talk to them and they to him. As the feature progressed Bumbazine and the other swamp critters abandoned conventional speech for a patois that was part Southern and part Li’l Abner.

By the time Pogo had reached his cute non-scraggly state, Bumbazine had departed. Animal Comics lasted for thirty bimonthly issues and closed up shop at the end of 1947. The first comic book that was chock-full of Pogo and nothing but Pogo was issued by Dell in its Four Color series in the spring of the previous year and titled Albert the Alligator and Pogo Possum. In these comic book stories, Kelly blended smart dialogue and broad knockabout comedy. By now many of the adults who were reading the stories to their younger children were as fond of Pogo as their kids. Especially of the dialogue and puns. There was also a lot of wordless action, with falling down, assorted crashes, explosions, true slapstick and Albert would quite often swallow something or somebody.

Kelly couldn’t always control his bawdy leanings, and old burlesque routines, including characters dressing up in drag, would sneak in now and again. At times he’d even manage to sneak in the punch line of a well-known dirty joke.

Kelly couldn’t always control his bawdy leanings, and old burlesque routines, including characters dressing up in drag, would sneak in now and again. At times he’d even manage to sneak in the punch line of a well-known dirty joke.

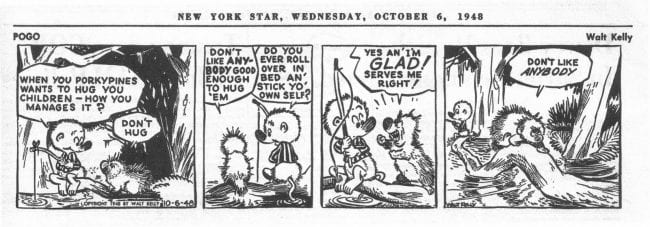

Pogo’s promotion to a syndicated comic strip was the direct result of Kelly’s adding another area of drawing to his list. He became a political cartoonist. The newspaper PM had been founded in New York City by Marshall Field III, the Chicago based heir to the Marshall Field department stores fortune and a liberal. He sold PM and its name became the New York Star on June 23, 1948. Michael Barrier speculates that “by 1949 Kelly had close companions among New York journalists, and it was presumably through such connections that he became part of the Star’s makeover.”

Noted political cartoonist Edmund Duffy was announced as going to work on the new paper, but that never happened. So Kelly took over the job of editorial cartoonist along with his other art department chores. He had liberal or, if you were on the other side, radical politics. He delighted in shellacking Gov. Thomas E. Dewey on his second try at becoming the President of the United States. He depicted Dewey as a robot who was mostly an adding machine and also made graphic attacks on the Republican Party, the Ku Klux Klan, and other scoundrels.

Having persuaded Western Publishing to grant him the comic strip rights to Pogo, he then persuaded the Star to use it as a daily strip and probably syndicate it. So on October 1, 1948 Pogo began running in the paper. Albert walked into the strip on the third day. And the other major swamp denizens from the comic book came straggling along: the grouchy Porky Pine, Churchy Lafemme, and Howland Owl. By the end of the first month, Albert the Alligator had almost eaten a butterfly and a widowed sparrow. The newspaper, however, failed to flourish and thrive. It folded on January 28. 1949.

Having persuaded Western Publishing to grant him the comic strip rights to Pogo, he then persuaded the Star to use it as a daily strip and probably syndicate it. So on October 1, 1948 Pogo began running in the paper. Albert walked into the strip on the third day. And the other major swamp denizens from the comic book came straggling along: the grouchy Porky Pine, Churchy Lafemme, and Howland Owl. By the end of the first month, Albert the Alligator had almost eaten a butterfly and a widowed sparrow. The newspaper, however, failed to flourish and thrive. It folded on January 28. 1949.

Kelly was able, quickly, to sell his swamp opera to Robert Hall, publisher of the New York Post. The daily debut was on June 6th of 1959. A very significant advantage of the new deal was that the Post Hall Syndicate would now be able to sell the strip to newspapers across the country and all over the world which they proceeded to do.

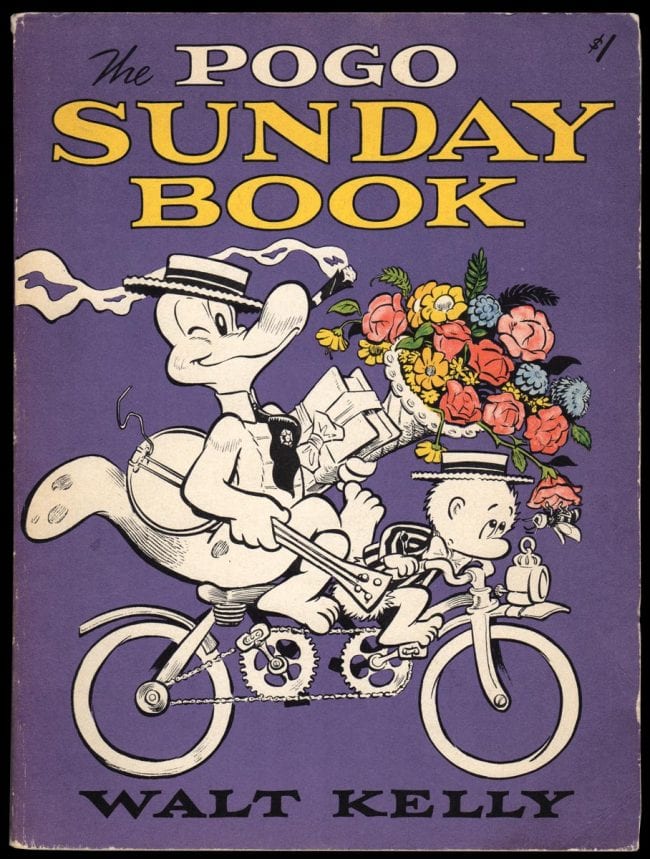

In the Pogo Sunday Book, published by Simon and Schuster in 1956, was a dedication that read

This book, like Kelly.

owes much to George Ward,

the best assistant

a boy cartoonist ever had.

Ward was Walt Kelly’s sideman and drinking companion from almost the beginning of Pogo’s syndication. Like Kelly, Ward had been a boy cartoonist and submitted drawings to magazines like Open Road For Boys and Tip Top Comics. They had a page where young cartoonists tried out, those who got a drawing printed won $1. In 1940 Ward joined the Marines and served in the Pacific. In the summer of 1940, he got a job with the Art Department of the Star. “One day Kelly walked into the art department with his Pogo daily and asked who could do some lettering for him and I said I could.” Kelly liked his lettering and that led to Ward’s becoming his official letterer. After the Star imploded, Ward became Kelly’s assistant, and sometimes ghost. He worked from his Greenwich Village apartment and later for two or three days a week at Kelly’s Connecticut home. “It was a great setup as I had a small apartment in Kelly’s house.”

The pair did quite a bit of pub crawling and in Manhattan the hangout of choice was Costello’s, a favorite spot of newspapermen and cartoonists, in the vicinity of Grand Central Station. James Thurber was in frequent attendance and the murals he drew on the saloon walls almost made the place a historical landmark.

I knew Ward in a casual way and often encountered him at the comics cons in Manhattan that were staged by Phil Seuling in the 1970s. Ward was a comics fan himself and collected originals and early DC comics like New Fun. He was sometimes accompanied by a couple of cute teenage girls whom he introduced as his nieces. Now and then the girls were different, but they were always identified as his nieces.

Walt Kelly’s finest hour took several years to unfold and all the while his income kept expanding. The unsettling and somewhat frightening decade of the '50s provided several high points for Pogo and his proprietor. On the positive side Simon & Schuster commenced reprinting Pogo in 1951, starting with paper-covered books of dailies. Tersely titled Pogo, it was followed the next year by I Go Pogo. All in all S & S did thirty-two books of reprints, followed by several more volumes that reprinted two early titles in one book. These books, especially the early ones, sold very well.

The '50s was also was also the decade when masses of college students discovered Kelly, bought those books, started speaking in Pogoese, considered him their idol, and invited him to lecture at or near their campuses. A large dark wind had begun to blow out of Wisconsin in 1950 and fear, panic and stupidity started spreading across America. The leading horseman of this latest apocalypse was the badly-shaven junior senator from the state Joseph P. McCarthy. He had served his country as a flyer during WWII, where he had earned the nickname of Gunner Joe because of the large number of enemy planes he had shot down. McCarthy, with great enthusiasm, had found a new target, namely communists in government, colleges, newspapers, television, radio, and anything else that happened to catch his fancy.

He in turn caught the attention of Walt Kelly and on May 1, 1953 he made his debut in Pogo, thinly disguised as a rifle toting wild cat name of Simple J. Malarkey. The use of the May 1 date was possibly not calculated, although May 1st was a day celebrated in many a communist county, including Russia. In a long essay on Kelly in 2011, author of books on popular culture and newspaper columnist Stefan Kanfer said that Malarkey was “surely Kelly’s most savage portrait…{He} had Malarkey stomping through Georgia, terrifying denizens with his shotgun and his attitude: Sentence first. Verdict after.” When asked once about his political views, Kelly replied that he was firmly against “the extreme right, the extreme left, and the extreme middle.” Kelly was now expressing many of the attitudes about politics in Pogo that he expressed back in his editorial cartoon days with the Star. When the ultra conservative John Birch Society reared its head a few years later, Okefenokee’s lunatic fringe formed the Jack Acid Society and ended up purging themselves out of business.

He in turn caught the attention of Walt Kelly and on May 1, 1953 he made his debut in Pogo, thinly disguised as a rifle toting wild cat name of Simple J. Malarkey. The use of the May 1 date was possibly not calculated, although May 1st was a day celebrated in many a communist county, including Russia. In a long essay on Kelly in 2011, author of books on popular culture and newspaper columnist Stefan Kanfer said that Malarkey was “surely Kelly’s most savage portrait…{He} had Malarkey stomping through Georgia, terrifying denizens with his shotgun and his attitude: Sentence first. Verdict after.” When asked once about his political views, Kelly replied that he was firmly against “the extreme right, the extreme left, and the extreme middle.” Kelly was now expressing many of the attitudes about politics in Pogo that he expressed back in his editorial cartoon days with the Star. When the ultra conservative John Birch Society reared its head a few years later, Okefenokee’s lunatic fringe formed the Jack Acid Society and ended up purging themselves out of business.

The 1992 book The Best of Pogo devoted some space to the Bunny Rabbit comic strips. Co-editor Bill Crouch, Jr. explained that “Walt Kelly is one of the few, and possibly the only cartoonist, who ever drew two cartoon strips for the same day. If he felt the political content of Pogo might cause some of his subscribing newspapers distress he drew an alternative. These he called the ‘Bunny Rabbit’ strips.” They ran in the middle Sixties. They did have a mild political tone but harkened back in looks to Kelly’s Animal Comics period.

His personal life had been growing more complex. As Kanfer pointed out, “In the cartoonist’s late middle age, a fondness for the bottle and for cigarettes, coupled with the ravages of diabetes, took a toll. Kelly had divorced, remarried, become a widower, and married again, this last time to Margaret Selby Daley. The wedding took place a few hours he found himself hospitalized for severe diabetes. A leg was amputated the next day. Kelly joked that he would plow on until he grew a new one,” but others took over most of the writing and drawing.” George Ward did some of that work. Walt Kelly passed away in 1973, just sixty.

Ward told me once that one of their favorite drinks was a milk punch laced heavily with rum, a concoction invented at Costello’s. Ward would usually, when Kelly was in better shape, have breakfast with him at Kelly’s—the breakfast hour was usually noon. Breakfast was usually a pitcher of milk punch. Possibly Kelly’s diet also contributed to his decline. Pogo had been losing papers in those years when the swamp was overrun with animal caricatures of politicians: Nixon, LBL, Hubert Humphrey, etc. Due to valiant efforts by Selby Kelly, other cartoonists, and members of Kelly’s family hung on for a time but then, like General MacArthur, Pogo and Albert and the multitude of other swamp critters just faded away in July of 1975.

Ward told me once that one of their favorite drinks was a milk punch laced heavily with rum, a concoction invented at Costello’s. Ward would usually, when Kelly was in better shape, have breakfast with him at Kelly’s—the breakfast hour was usually noon. Breakfast was usually a pitcher of milk punch. Possibly Kelly’s diet also contributed to his decline. Pogo had been losing papers in those years when the swamp was overrun with animal caricatures of politicians: Nixon, LBL, Hubert Humphrey, etc. Due to valiant efforts by Selby Kelly, other cartoonists, and members of Kelly’s family hung on for a time but then, like General MacArthur, Pogo and Albert and the multitude of other swamp critters just faded away in July of 1975.

In 1989 a new version returned to newspapers under the name Walt Kelly’s Pogo. It was written by Larry Doyle and drawn by Neal Sternecky. Not a bad looking impersonation and well intentioned, but it only proved that genius rarely strikes twice in the same place, or in the same swamp. Pogo been enjoying a sort of renaissance of late. The many books that reprinted the comic had dropped many strips, nearly half, to make them fit the number of pages allowed for each book. Fantagraphics has been issuing the complete run.

A belated salute for Kelly’s 100th birthday.