Are you familiar with Lewis Trondheim?

Yeah.

He has the wackiest question of them all.

Huh.

He said, “All the famous cartoonists are doing comics and music and sports. What sport do you practice?”

Famous cartoonists do sports?

I know! I had the same reaction, so I wrote him and I said, “No American cartoonist does sports, what are you talking about?”

Yeah, that’s weird. We’re the most unsporty group of people.

Right. So he sent me this list and apparently European cartoonists are all into sports — it’s unbelievable. [Crumb laughs.] He wrote back and he said, “I play squash; Baru, the last Angoulême’s president was a sports teacher at school; Christophe Blain and Boucq are doing body-building; Jean-Yves Ferry, the new scenarist of Astérix is a marathonian; Mezières plays tennis. The young French protégé Bastien Vives is swimming.”

Huh.

All these European cartoonists are into sports.

Huh. Yeah, I think cartoonists here in France are more well-adjusted people than they are in America. [Groth laughs.] I don’t do any sports. I do zero sports.

Zero. [Crumb laughs.] Never have.

No. I do take a walk once in a while. [Laughs.] Not really a sport.

Well, that’s probably why your knees still work.

[Laughs.] I hate sports, actually.

You don’t watch sports, right?

No. The only interest I have in sports is Serena Williams. [Laughs.]

Well, you’re probably not that interested in her sport.

Tennis shmennis, I could care less about her tennis technique.

[Laughs.] Right, right. [Crumb laughs.]

I wrote him back and said, “That’s a weird fucking question,” and so he wrote another one.

He asked, “Do you know that if you hadn’t drawn all these little hatchings always and everywhere on your panels you’d certainly have had time to draw 50 more books?”

That’s absolutely right. [Groth laughs.] I regret that I didn’t start doing Genesis with the brush. It would’ve taken me half as long.

Really?

I thought of it before I started, just using the brush, but then once I started with the pen I couldn’t very well change in the middle.

So why did you choose the pen over the brush in the first place?

It’s habit.

I remember talking to you when you were first learning to use the brush and you said it was difficult but mastering it was incredibly satisfying.

Yeah. Comic books lend themselves very well to the brush.

But when you say habit, you’ve used the brush, so you were in that habit as well, right?

Well, I kind of gave it up. I stopped using it sometime in the early ’90s, late ’80s. I just went back to the pen out of habit. The pen was my first instrument, it’s like a language, you know. The pen was my first language; the brush was like a second language. It’s funny, because I was getting really proficient with the brush when I went back to the pen. And also I think, like for doing Mr. Natural and that type of stuff, I didn’t think the brush was appropriate, the brush was more for illustrational stuff.

Your blues biographies were all brushwork.

Yeah, the Jelly Roll Morton thing, and Charlie Patton and all that. For getting the noir effect, the brush is really great.

It seemed perfectly appropriate. Do you think the drawing in Genesis would’ve been as good if you used a brush?

Maybe better, who knows? One thing I know, it would've got done a lot sooner if I'd used the brush.

Arnold Roth asks, “Did Harvey Kurtzman ever request that you redo or alter any of your original work? If yes, what happened?”

Hmm. Kurtzman, when I was working for Help, he gave me lots of suggestions but it wasn’t about the drawing so much, except for that criticism of what happened to my drawing after I started taking drugs. He never made any detailed suggestions about the drawing. He would tell me, like when I did that Bulgaria strip, “Go for the jokes more. Think like you’re writing for the guys on the corner.” [Groth laughs.] Very sage advice.

Must’ve been a bit hard to do with your grim drawings of Bulgaria.

Well also, I didn’t really have any guys on the corner in my mind, I didn’t hang out on the corner with the guys when I was a kid, when I was young. [Laughter.]

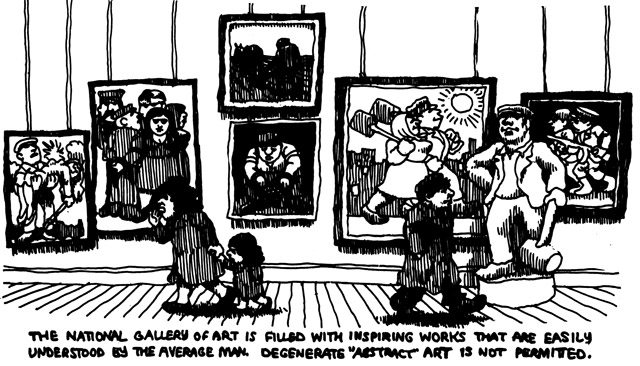

But you have to think of that kind of entertaining communication to people when your doing cartoons. You always have to keep it entertaining; you can’t expect them to come to you. I don’t like that when I see people do arty stuff and they expect the audience to bend over backwards to understand what it is they’re doing. That doesn't work. You can be deep: you don’t have to talk down to people. But you gotta communicate, you gotta keep them interested.

Well, you were never particularly interested in doing that, were you?

In doing what?

In keeping people interested.

Hell fuck yeah! What, are you kidding?

I always thought you were more interested in expressing yourself.

I was interested in both — of course you gotta keep people interested. You can’t presume they’re going to read it if you don’t put out something toward them. You gotta entertain them, you gotta reach them. A lot of the challenge of any kind of medium where you want to really reach people is to figure out how to do that and still keep it honest, and not just pander — so much media is just pandering. That's the whole problem with most cartooning and most movies, most everything, pop music. The movie industry is particularly bad that way, because there’s so much money involved in making any film, or an HBO program or anything. The people with the money worry that if they don’t pander they’re not going to get the audience, so they just turn every idea to shit. [Groth laughs.] Because in the process of trying to simplify it, dumb it down or whatever, they’re just so worried that if it’s too subtle, it’s not going to reach people. They just kill every good idea. Most movies are just good ideas turned to shit. [Laughter.] Even good movies.

My theory of Hollywood is that the people who produce the movies are actually producing what they themselves love. So they’re actually not pandering.

Well there’s that too. The people with the money have such bad taste themselves. This is what Terry Zwigoff says, that it’s shocking what bad ideas they have. [Laughs.]

I think we’ve reached the stage where people don’t have to pander — they’re self-pandering.

[Laughs.] Yeah, but even when they think they’re doing something good and high-minded, once it’s dragged through the machinery, the processes just turn it to crap. [Laughter.]

I assume you don’t watch a lot of contemporary movies.

Not a lot, no. Not a lot. Occasionally: not much.

I find myself watching more and more old movies. Silent movies…

Oh yeah, I’ve been watching a lot of silent movies lately too, actually, because Pete Poplaski’s here, and he’s a real connoisseur of silent movies, so he’s turned me on to some great silent movies. Great ones.

You know, 80 percent of all silent movies made have all been destroyed.

Lost?: 80 percent, really? That much?

Yes, yes.

Wow. Whew! That’s staggering. There’s a lot of bad ones too. Pete tells me there were companies that specialized in churning out just really second-rate crap. There’s gotta be hundreds of bad silent movies. But the small companies that made inferior stuff are probably mostly what’s lost.

Well, that would be reassuring.

Because, you know, they didn’t make a lot of prints, and nobody cared to keep them. When the company went out of business they just threw everything away.

But God knows how many decent or even good movies were lost.

We don’t even know whether they were good or not.

Well, speaking of shitty movies: let me move on to three questions Bill Griffith has for you. These are real ringers. The first is [laughs] — obviously I don’t have enough tape for this, but — “What do you detest most about the modern world?” [Crumb laughs.] I’ll just sit back for about 20 minutes.

Detest most about the modern world?

Yeah.

Well, as compared to in the past when you had brutality and cruelty and everything, and we still have, so what’s specifically detestable about the modern world that’s different from times past is that now they’ve developed such a very clever way of perception management and persuasion and deception, that this has become huge and elaborate. Millions of people earn their livelihoods involved in this massive deception and trickery, and the selling of stuff and ideas — they've become so good at it. That’s really detestable and despicable, and to stay alert to that is a full-time job. [Laughs.] You’re constantly bombarded with this sales pitch — constantly. That, to me, is really hateful. And it’s the kind of banality of evil type of thing, most of the people doing that for a living have no idea that they’re involved in something that might be harmful or evil.

[Laughs.] You just compared marketing people with Nazis.

Well, yeah.

[Laughs.] What’s my point?

The public relations industry: the stuff that they push, and it’s so amoral. It’s a kind of fascism of a new kind that people don’t recognize as fascism because they just think of guys in military uniforms goose-stepping and dragging innocent people off to concentration camps. It’s not like that, but all the secrecy and stuff just creates a web of paranoia so that we’re all constantly trying to figure out what the conspiracy is. It just creates a horrible paranoia through the whole society. I just read an article in the New Yorker, I think it was, about the National Security Agency.

Oh, yeah.

I was just shocked. I was shocked. It’s just the number of people that work in that agency, and they have this five-thousand-acre “campus” that’s somewhere outside of Washington. There’s thousands of people working in this thing. The article said something like two million people in the United States have clearance for classified information in documents. [Laughs.] Two million. [Laughs.] That offsets the two million that are in jail all the time. [Laughter.]

They’re the ones putting them in jail. Well, they’re all working on behalf of our safety.

That’s the argument, yeah. Keeping us secure from terrorists and shit. And when you start to examine that, it’s such a horrendous load of crap, that’s just scary. Sometimes you think, “Jesus, I know too much, they’re going to get me.” By speaking on the telephone to you, they’re picking up this conversation, they’re gonna, you know… [Laughs.]

You’re living in France now and you’ve lived there for 20 years; do you think the social and cultural marketing apparatus is different there than in the U.S.?

Yeah, it is. It’s less corporate-controlled here. Partly it’s because the old ways are so deeply ingrained here, and the French people are very proud of their old ways and they resist total corporatization of their culture, but it’s happening. It’s really different from when I first came. I was really amazed when I first came here how old-fashioned things were, but that’s changing, people are more Americanized. They’re bigger, they’re fatter, they dress more slovenly like Americans [laughter]; they eat more snack foods. When I first came here, French people did not snack. There were no snack foods in the market. [Laughs.] Now, of course, they have shelves of potato chips and crap like that just like in America. And there’s impulse items at the checkout counter now. There wasn’t when I first came. [Laughs.]

So it’s happening, but more slowly.

Yeah, and just not on the scale, there’s some resistance to it here. Of course you go to some country like the Czech Republic, and it’s sad, they just caved in to that completely when the Soviet Union broke up. It didn’t take the Western corporate financial powers long to move in there and just completely grab that country up. So in beautiful cities, like Prague, there’s a McDonald’s every three blocks. [Laughs.]

Oh, man that’s depressing.

[Laughs.] But here there’s more resistance to that. France has more cultural savvy and more pride. The Czechs were just demoralized people.

But the way you described it, even the French aren’t going to able to resist, ultimately.

Oh boy, it’s a really hard thing to resist, and the average ploucs here, the average person here…

[Laughs.] Ploucs?

Yeah, ploucs. They have very little defense against those things. They're dazzled by it, just like Americans, but there’s enough forces here of resistance against that, there’s a level of intelligent people that fight against this. [Nicolas] Sarkozy is a completely pro-corporate guy: he’s bad news.

(continued)