Oskar Lebeck, editor, writer, cartoonist, settled in New York’s Westchester County, just across from the Connecticut border, along with his family, in the late 1930s. And he, with help from some neighboring young cartoonists, developed some of the bestselling comic books of the 1930s and '40s. These included Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories, The Funnies, Looney Toons and Merry Melodies, Popular Comics, Crackajack Funnies, Super Comics, Little Lulu, Animal Comics and Fairy Tale Parade.

Michael Barrier’s impressive and thorough 2015 study, Funnybooks, provides a substantial and detailed account of Lebeck’s life and times. According to him, “Oskar Lebeck was born in Mannheim, Germany, on August 30, 1903 and emigrated to the United States in March 1927.” He had worked in the theater as a set designer for Max Reinhardt and in Manhattan he held similar jobs with Earl Carroll and Ziegfeld. He later went to work for Western Printing’s Whitman Division, which printed the Dell comic books.

Put in charge of the comics that appeared under the Whitman and the Dell umbrellas, Lebeck brought in a crew that included Jim Chambers, Bill Ely, and Alden McWilliams. All three artists lived around Connecticut at various times and all of them ended up residing in the Nutmeg State. Every few weeks Lebeck would drop in at Ely’s house, where they all gathered to work. He’d gather artwork, distribute assignments and pass out checks.

All of Lebeck’s aforementioned trio entered the funny book field in its infancy and worked for such pioneering figures as Major Nicholson, Vin Sullivan, M.C. Gaines, Everett “Busy” Arnold, and Whit Ellsworth.

Bill Ely was born in 1919 and studied at Pratt Institute in Manhattan. He helped finance his studies by doing illustrations for the still thriving pulp magazines. Early in 1937 he heard that Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson was looking for artists for his fledgling line of original material comic books. He and his artist friend from Pratt, Jim Chambers, decided to drop in on the Major’s humble offices in NYC to show him their portfolios. They both got assignments on the spot and the promise of $5 a page. Often with the impecunious Major these promises took a while to be fulfilled.

He called himself Will Georgi (a family name) because he wished to reserve his real name for more serious illustration jobs. One of the early features he took over was Sandra of the Secret Service in More Fun Comics, one of the first comic book features starring a woman. An earlier artist had been Charles Flanders, who modified his style to emulate that of Alex Raymond and took on the Secret Agent X-9 comic strip and within a few years the new The Lone Ranger comic strip. Over at New Adventure, Ely was assigned the depicting the daring-do of Dale Daring. She was another adventuresome lady who got in trouble on a world-wide basis. Next came Larry Steele, a hard-hitting district attorney, who flourished in Detective Comics, initially in pre-Batman days. Although Ely worked for the Major for most of a year, he told me that he never actually met him. After Nicholson was forced to sell out to DC, the page rate went up to $6.

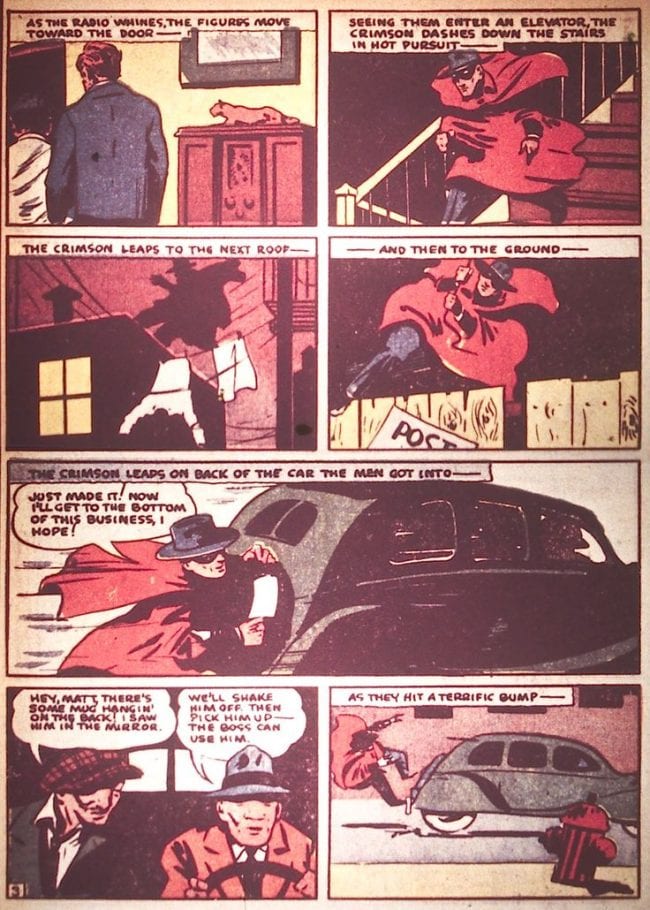

The two newspaper comics artist who had the most influence on comic book cartoonists in the '30s and '40s were Milton Caniff and Alex Raymond. Ely and Jim Chambers were definitely more influenced by Caniff. Chambers was a few years older than Ely and worked up his own serviceable version of the Caniff style ahead of him. Prior to jumping into comic books he’d done some pulp magazine illustration, one of his clients being Spicy Detective Stories. His major assignment with DC was on The Crimson Avenger in Detective Comics. This masked and cloaked crimebuster made his debut in #20 (October 1938) and appeared on his first cover two issues later. He was one of the first costumed heroes, but a lot of his attire was inspired by pulp magazine heroes. And he also joined the ranks of heroes who wore fedoras, a very popular head gear in the years just prior to America’s entry into WWII.

Basically The Crimson Avenger is a blatant swipe of The Green Hornet who was born on the kilowatts of radio station WXYZ in Detroit a few years earlier. The Hornet's real name was Britt Reed, the editor of The Daily Sentinel, presumably in Detroit, but he got fed up with the law’s delay and cooked up a gas gun that would knock out all sorts of miscreants with no bloodshed. He had a souped-up car called the Black Beauty and a loyal "Asian" driver named Kato who was the only one who knew that his boss was a crime fighter whom the police and the FBI believed was a master crook. The car played The Flight of the Bumble Bee on its horn. Apparently because nobody had gotten around to composing The Flight of the Hornet. Kato was a well-spoken fellow and a chauffeur who was a wiz at chasing crooks and dodging the forces of law and order.

Now then, back to the Avenger. He too was the editor of a large metropolitan newspaper. His name was Lee Travis and he had a smart uniformed "Asian" chauffeur named Wing How who was in on his secret. Travis, too, had invented a gas gun with which to confront the underworld. Chambers did an okay job on the feature, though he could get much better in the early '40s. And he didn’t draw Wing as a bucktooth speaker of pidgin English that he would be converted into later.

When Bill Ely learned that Whitman was paying $7.50 per page, he paid a call on Oskar Lebeck and switched to drawing for Popular Comics. He’d by now developed his own variation of the Caniff approach. He drew The Hurricane Kids, plotted and scripted by Lebeck. The feature dealt with two young men who were shipwrecked on an island that was densely populated with Prehistoric creatures and inhabitants. Hal Roach’s One Million BC, starring Carole Landis and Victor Maure, came to movie theaters about this time. A few issues later, in Popular #47, Lebeck continued his plan to keep cutting down on comic strip reprints by giving Ely another new feature to draw. This was about a handsome couple from a distant, and the far-advanced planet of Antaclea, who visit Earth. Although it was one of the earliest husband and wife teams in the superhero field, it was titled Martan the Marvel Man. Ely used the pen name of William Kent and the script was by Lebeck, Ely told me, under the name G. Ellerbrock. Ely drew the covers of #47 and #48, both showcasing the Martan couple. Their name lacks one letter of the word Martian. Lebeck was very much concerned with Fascism and the Nazis. Martan and his wife Vanta ditch their spacecraft and futuristic outfits. acquiring contemporary clothes they dine out on Earth food and attend a Broadway show. The real comedy that Lebeck picks for them is Hellz-a-Poppin, which possibly had a double meaning for him. It was successful and long running screwball comedy with Olsen and Johnson. The Martans enjoyed it.

As with many alien visitors to come, America called out the troops and the law and tried to destroy them. Martan’s opinion of the society they’ve landed in are not positive—“It seems that all mankind is using its inventive genius to invent new ways of self-destruction—what a dark Age!” The feature lasted about two years, never giving much competition to alien visitors like Superman. With the 60th issue Popular replaced it with Superman and Son by former pulp magazine illustrator Ralph Carlson.

Lebeck was also pepping up Crackajack Funnies and added Ellery Queen early in 1940. Bill Ely began on that with the cerebral sleuth’s second adventure. Ellery was a multi-media hero, appearing in books, movies, the radio and comic books. The scripts were based on the radio show. Fred Dannay, the plotting half of the book writing team, once told me that he and his cousin Manfred B. Lee didn’t write the comic scripts but turned over their radio scripts to be adapted.

The third member of Oskar’s triumvirate, Alden McWilliams, had worked in the King Features bullpen as one of the several ghosts for Chic Young’s minimally talented brother Lyman on Tim Tyler’s Luck. Others who greatly improved the look of the jungle adventure strip were Alex Raymond, Charles Flanders and Nat Edson. One of Williams’ specialties was the depiction of airplanes and other instruments of war. The fact that World War II was very much on the horizon provided him with opportunities. He commenced working for Lebeck with the 7th issue of Crackajack near the end of 1938, drawing an aviation feature about Captain Frank Hawks--AirAce. Hawks was a real record breaking aviator. He’d been a World War I flyer who’d become a barnstormer and then set out to win air races and set aviation records. He was hired by Texaco Oil to fly around the country and put on flying exhibitions and take folks up for a flight at fairs. He estimated taking over 7000 people up in the air. Time called him a “publicity flyer.” Post Cereals used him in an advertising Sunday comic strip for Post Bran Flakes and formed the Frank Hawks Air Hawks, offering a pair of silver wings as a premium. On August 23, 1938, Hawks was killed taking off from the private golf course of a wealthy client. The aircraft did not manage to clear the telephone wires and Hawks and his passenger were killed.

McWilliams also drew Speed Bolton, Air Ace for The Funnies and he introduced Stratosphere Jim and His Flying Fortress in the 18th issue (Dec 1939). He drew this giant super plane on only one cover (Jan 1940) which contained the blurb “most Sensational Feature of the Year The FLYING FORTRESS.” The real life Flying Fortress was developed for the USAAF in the 1930s by such aircraft oufits as Douglas and Martin. It was a B-17and it was used for precision bombing during World War II.

The Crackajack version was more futuristic and gadget ridden. It’s probable that Lebeck, a Sci-Fi buff, scripted this. The Dell/Whitman magazines also used adaptions of B-movies and radio shows. McWilliams was one of the artists who drew adaptations of Phillips H. Lords’ Gang Busters. He spent four years in the US Army and got home in 1946. He apparently signed with Will Eisner’s shop and drew airplane strips for the Quality line—Secret War News for Military Comics, edited by Eisner, Spitfire for Crack Comics, etc. McWilliams participated in the D-Day invasion. These latter features were apparently prepared before he went overseas.

Jim Chambers was a star contributor to Popular Comics in the early 1940s. The Voice was introduced in #53 (July 1940) and was billed as “the invisible detective.” Universal Pictures has released The Invisible Man Returns in 1940, with Vincent Price, in one of his pre-mad doctor roles, and that may have provided inspiration. And The Shadow Sunday afternoon radio show described Lamont Cranston’s lady friend Margot Lane as the only one who knew to whom “the voice of the invisible Shadow belonged.” Chambers provided the cover of the introductory issue in a style slicker than the one he’d used back at DC. The Voice’s crew consisted of Tim Brant’s pretty red-haired secretary, Curly Rand, and Prof Bert Wilcox, who discovered the process that converted Brant, “New York’s cleverest private detective”, into an unseen operative. By slipping on a suit of transparent cellulose that had been treated with a special ray Wilcox had invented, Brant became The Voice.

Turning more real people into comic heroes, Lebeck gave Chambers the job of drawing the adventures of Clyde Beatty, the then famous animal trainer and circus performer, for Crackajack. The stories were set in various dangerous locales around the world and sometimes involved Beatty in the Pacific War. Chambers made no effort to do a realistic portrait of the lion-tamer and used his standard handsome dark-haired hero. The scripts were written by Gaylord Dubois, one of the most prolific writers in comic books. He also provided most of the scripts for Dell’s Tarzan comic book, during Jesse Marsh’s long run and beyond. When Chambers entered the Marines, Beatty’s deeds were drawn by lesser hands.

Turning more real people into comic heroes, Lebeck gave Chambers the job of drawing the adventures of Clyde Beatty, the then famous animal trainer and circus performer, for Crackajack. The stories were set in various dangerous locales around the world and sometimes involved Beatty in the Pacific War. Chambers made no effort to do a realistic portrait of the lion-tamer and used his standard handsome dark-haired hero. The scripts were written by Gaylord Dubois, one of the most prolific writers in comic books. He also provided most of the scripts for Dell’s Tarzan comic book, during Jesse Marsh’s long run and beyond. When Chambers entered the Marines, Beatty’s deeds were drawn by lesser hands.

Military service also interrupted Bill Ely’s comic book career, in 1943. After the War, he again worked for Whitman/Dell. His style had become tighter and more detailed, well suited to realistic hard-boiled crime and detective stories he did during that period. He did a one-shot Zorro comic book in 1949, before the California masked avenger became a Disney property. In the middle 1950s he returned to DC after doing quite a lot of true crime stuff for comics like Real Clue. The fact that he’d worked for DC during the company’s startup days “didn’t mean anything” and Ely sometimes felt that his being an old timer was a disadvantage. However, for the next decade or so he was one of their most productive and dependable artist in the crime, horror, fantasy and science fiction categories. He did numerous stories for House of Secrets, House of Mystery, etc. He avoided superheroes and the closest he came was a few issues of Rip Hunter, Time Master.

Back home in 1946, Alden McWilliams re-upped with several comic book publishers. He drew a tough private eye named Steve Wood for National Comics, an operative in the manner of such early radio and TV shamuses as Martin Kane and Sam Spade. He drew Dick Cole for Blue Bolt and did illustrations for pulp magazines, many of them Fiction House titles. Reunited in 1952 with his former boss, Oskar Lebeck, he assumed the artwork on the new comic strip, Twin Earths.

This was a complex science fiction venture, daily and Sunday. It was crammed with complex mechanisms, political intrigues, pretty women and took place in a slightly prosaic tomorrow. Both Earths closed up shop nine years after launching. McWilliams also had a sideline as an assistant and ghost on comic strips in the 1960s and early 1970s. He lent a hand on Rip Kirby, Buck Rogers and On Stage. He is often listed as an assistant on Don Sherwood’s Marine sponsored Dan Flagg, but in truth, McWilliams drew the whole thing (which was usually also ghost written). His last go-round with comic strips was a new Publishers-Hall Syndicate strip. Dateline: Danger, written by John Saunders. Saunders was the son of Allen Saunders, a syndicate editor and writer for several decades. He had written Chief Wahoo, Steve Roper, Mary Worth and (anonymously) Kerry Drake. Alfred Andriola, who was credited with this last strip, was another Don Sherwood type who never wrote nor drew his creation. A fact that the senior Saunders told me, in profane terms, the one time I met him at Comics Council meeting.

Dateline: Danger flourished, if that’s quite the word for it, from 1968 to 1974. The gimmick here was that one of the two intelligence agent stars was an African-American. Both were pretending to be international newsmen. To underline his color, his name was Danny Raven. Many comic strip critics and historians did not take this comic to their bosoms and Maurice Horn called it “blatantly” offensive. That was because of the fact it was quite obviously a rip-off of the basic premise of I,Spy., the television show starring Bill Cosby and Robert Culp. Still it did manage to hang on for six years. Alden McWilliams passed away in March of 1993 at the age of 77.

Bill Ely departed DC in the mid-60s and returned to Whitman, which was calling itself Gold Key by this time. He did work for such titles as Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. In the mid-70s, after nearly forty years in comic books he retired, but not from art. For most of the rest of his life he devoted himself to full time landscape painting. His specialty was New England scenes with covered bridges, boat docks and sailboats. He produced a great many impressive canvas. He didn’t considered himself a great painter but a pretty good one. Spring and summer and fall, he would travel each weekend to one or two of Connecticut’s many malls, set up his easel and his canvas chair and start painting. He’d tack up a color photo that he’d taken of a site, maybe this time one of the colorful 19th Century inns or a collapsed sugar mill. Ely charged from $100 to $200 for a painting. He made a comfortable living this way. The best part was that it was fun. He told me that was something he wasn’t able to say about his last years in comics.