There are times that you can watch a work, page by page, slowly but firmly slip out of the control of its author. Moby-Dick may have started as something like a straightforward whaling adventure, before it became clear with every passing chapter that Melville was caught in something more baffling and gargantuan than even he could wrap himself around. The Lord of the Rings was meant to be a charming fairy tale about Hobbits. Proust went in search of lost time, when all he wanted was a cookie.

20th Century Men, a 2022-23 Image Comics miniseries newly available in book form this week, began as a simple, Alan Moore-ish deconstruction of the superhero archetype behind Marvel Comics’ Iron Man. By the time it ended, it was something akin to comics’ version of War and Peace, or perhaps Grossman's Life and Fate: a vast, sprawling, sometimes hallucinatory alternate history of the Soviet and American empires, viewed through the cracked lens of the superhero idiom. To call it a study in the causes and consequences of imperialism, or the nature of history, is both correct and unforgivably reductive. Whatever thesis statement the comic makes is ultimately secondary from the manner in which it makes it: a series of striking and narratively contained vignettes, anchored by the weight of richly-drawn characters, and a dizzying array of artistic styles made somehow uniform as a composed whole.

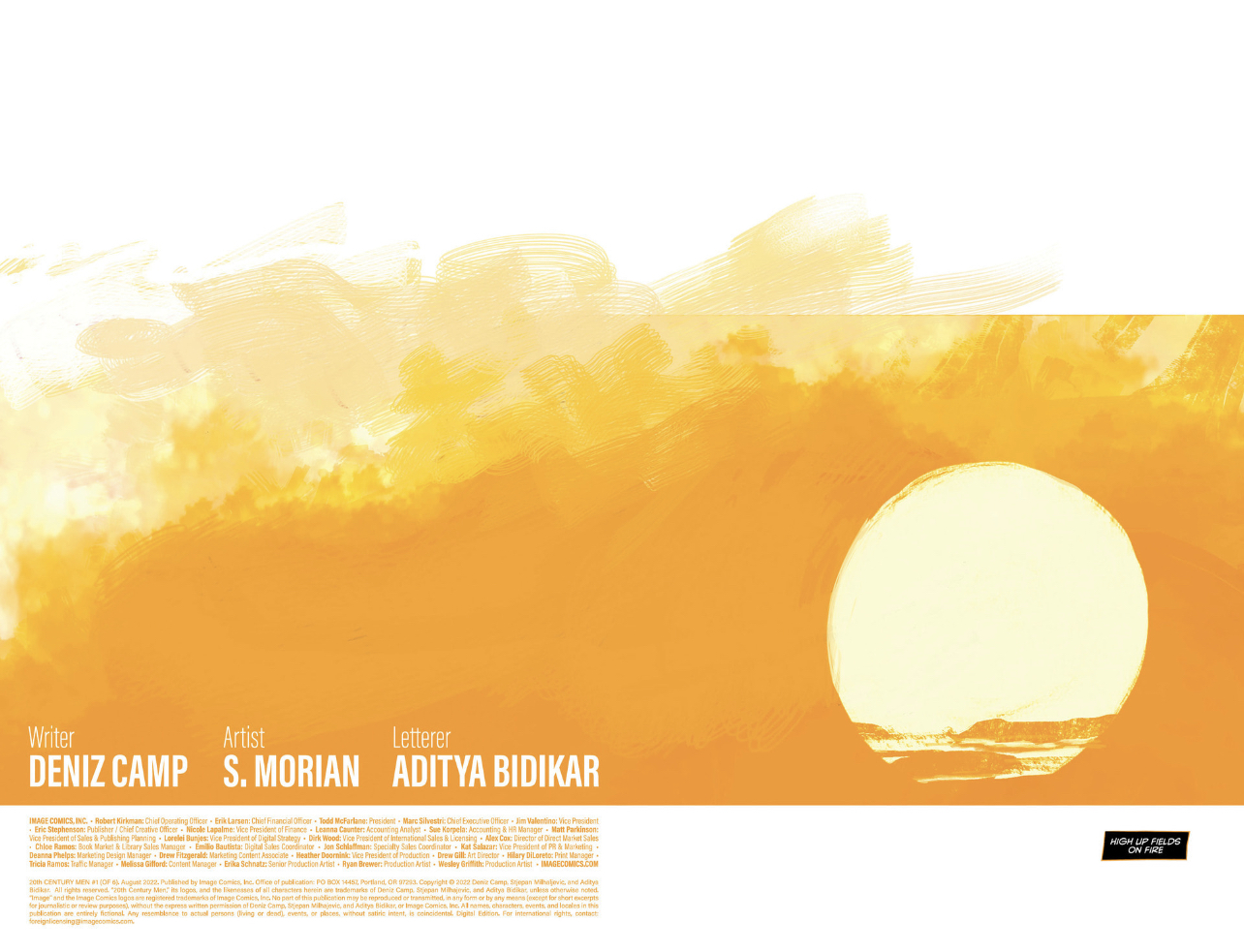

Like orbiting components of an atom, the story lets us glimpse its characters and their fragments of history as they spin in turn across some elusive shared significance at their center. Petar Platonov, the gothically grotesque product of the Soviet war machine whose brutality does little to conceal a crippling sense of vulnerable fear. A Reaganesque American president with the power of a super-soldier and the embodied moral righteousness of capitalist fervor. Egon Teller, a sad, fading reminder of the betrayed promise of 20th century science. And Azra, dignified, steadfast object of Platonov’s affections, whose story, we only realize in the comics’ closing chapters, this has been all along. They are, viewed from the distance of space and history, a patchwork quilt of time’s passage and the meaning of nations and peoples. But it is their individual voices and forms that linger with us, having seen them through the close-in framing of a panel or page. In the end, whatever holistic meaning the series holds is contained in a single image of an Afghan child, silhouetted with a kite against the brightness of a burning sun.

For writer Deniz Camp, who hatched the premise from which the comic grew, the series amounts to a dramatic leap forward in a career that might until now have been characterized as full of potential. The ambition of his storytelling is here equaled by a confident control over his narrative structure, with each chapter designed as its own discrete experiment in form. One issue is a running monologue of a scientist’s last days, narrated with the maudlin tone of a late-period noir. The next is a reporter’s journey through a Dantean hellscape of the Soviet-Afghan War, in search of a truth that slips further away the deeper he ventures. Still another is told entirely through excerpts from fictitious historians and newspaper clippings from the book's alternate history - a comprehensive account of things that never were, told without any of the laborious exposition that so frequently derails what’s generously termed “world building” in comics. It is an altogether bravura performance that establishes Camp as, beyond question, a mature and brilliant talent.

Stipan Morian is an artist who works in the idiom of European comics, drawing from a long tradition of satirical caricature and unflinching hyperviolence. For an anglophone audience, the closest point of comparison may be the British tradition of someone like a Simon Bisley, but Morian demonstrates a range and precision that defies any simple attempt to categorize his style. At times, particularly in close-up panels of faces, or illustrations of human (or once-human) bodies, his jangly linework gives way to an illustrative style that resembles a charcoal sketch. At other moments, he mimics the look and design of medieval Afghan artwork. What is most apparent, however, is his facility for shifting the language of storytelling from page to page without disrupting the momentum of the script: there is no dependable template or standardized format for this story; no nine-panel grid or typical grid-splash-grid alternation. Every beat of the story invents its visual language anew in an echo of Camp’s shifting text - or perhaps it’s the other way around.

The same can be said of the lettering work from Aditya Bidikar, who over the past several years has rapidly and definitely established himself as one of the leading craftsmen in his field. There is nothing flashy about Bidikar’s work; no self-regarding and showy experimentation in fonts and balloon shapes in the Todd Klein tradition. Rather, there is a confident control over the aesthetic design of every page, fluidly setting the momentum of scenes through the placement of the not-inconsequential number of words that occupy the book’s text. Within a relatively uniform font, Bidikar nevertheless manages to establish a distinctive style that demarcates different characters and points in the narrative, clarifying story points that the reader may never even realize might otherwise have needed clearing up.

We can see the way this creative team acts as a cumulative whole in two consecutive sequences from issue #5. In the first, scenes of apocalyptic Russian civil strife are overlayed by captions quoting from the Trotskyist writer Varlam Shalamov on the fracturing of Communist ideology: the unbearable momentum by which the dreams of socialism divide and subdivide into mutually incompatible factions, until all that remains is the prospect of the violent conflict we see on the comic’s pages. The artwork throughout the sequence is tight and controlled, sequenced in enclosed panels save for one wider splash of a farmer wielding a pitchfork at the reader in threat of implicit violence. The linework is sketchy; the colors are muted in shades of steely blue.

This is the late-Soviet vision of history - the curdling of noble aspirations of human equality into a mere war for domination of one side over its rivals. It is the sad reality of what comes of a utopian society that can only preserve itself through the conquest and subjugation of those who would undo it in turn. It is a vision that leads, through the unblinking process of historical dialectic, into an endless and final war for nothing at all.

A few pages later, we do not even need words to tell us that we have entered a different world. The colors now are vibrant and gold; the images expansive and richly-drawn. Even the word placement is looser and more relaxed. Here we have turned our attention to Azra, in her moment at last to defy the expectations of her would-be Russian saviors, and speak the truth she has known all along: that history is not interposed by the conqueror, but lived in the experienced of those they would conquer; that the gift of civilization is nothing more than the violent, forcible removal of human lives and hopes; that the ascendance of ideology is the sacrifice of humanity; that long after the Soviet and American empires fall, those they strove to eradicate will endure.

That any of this is clear to the reader, and that it carries such a devastating and undeniable emotional weight, could only be achieved by three creative energies working in tandem with one another. This, in every respect, is a comic of collective creative effort.

To explore it further, and to understand the thought, the process, and the manner of its creation, I sat down with the three creators for a frank discussion about their work on 20th Century Men. The dialogue that follows is, I hope, some small illumination of a comic that will invite and demand much more critical attention in the years to come.

-Zach Rabiroff

Zach Rabiroff: What I’d like to do is start with some background on each of you, and then work our way forward to the actual series. Not just your experience in comics, but where you’re from, how you became interested in art and storytelling in the first place, and then how you decided to make it your livelihood.

Deniz Camp: Artists first.

Stipan Morian: My story is wild. It’s really wild. I was living in different countries, and in different places. I learned to read by reading Italian comics while I was living in Germany…

Camp: Italian comics in Croatian while living in Germany.

Morian: Italian comics in Croatian, yeah. So after that it gets complicated. [Laughs] I [was] reading comics since the '70s, Italian comics about American characters. The American Revolution was the topic of one [in] particular. And they’re all set in some invented United States, not absolutely real, because sometimes you have Vikings there; sometimes you have aliens, and Frankenstein is around.

Sounds like a hell of an American Revolution. So, obviously at some point you were living in Germany, but tell me about that a little bit: walk me through your biography into your early comics career.

Morian: I was living in Germany because my grandparents were imported workers from Yugoslavia. My grandfather was working in construction, and my grandmother was cleaning stores at night. So I was living with them, because my parents were young and poor, blah blah blah. I’ll tell you this: when I was growing up, we had a wonderful comics scene in what was called Yugoslavia, which is a country that doesn’t exist now, because they were printing comics from all over the world. You had American comics, British comics, Spanish comics, Italian comics. You have Hugo Pratt in one, and then you have Hal Foster, and then you have something completely new from Marvel that just appeared in the United States, you know?

I was always drawing. I was publishing comics when I was in elementary school, in our own magazine that got prohibited by the school authorities - because, of course, it was not under the control of any socialist regulatory authority. So I was prohibited at 13, I think, for the first time. But since I met Deniz, he somehow got me into making comics for real.

Aditya Bidikar: I think Deniz does that. He talked Hassan [Otsmane-Elhaou] into becoming a letterer as well. Like he’s a pastor.

Let’s follow that thread, then. Deniz, how had you moved into writing in the first place?

Camp: I did not really think to be a writer for most of my life. I was going pretty heavily into the sciences: I studied cell molecular biology as an undergraduate, and then I went to medical school and did medical work abroad after that. And it just wasn’t the work I wanted to do. I was very happy to be able to help people, and that made me feel very good, but the actual process of doing the work was often very tedious, especially in the United States, which is why I went abroad. So I started to think about other options, see if I could kind of ignite a passion.

I worked in a small, rural fishing village on the coast of Ecuador, and in Buenos Aires outside of the city, and in Istanbul, which is where my father is from. And so I moved to New York with really no options and no prospects, and no idea what I wanted to do, and I kind of bummed around for a while. I didn't really have a place to stay, and I didn't really know anyone. And I’ve always really loved comics. I used to read and study Grant Morrison or Alan Moore comics, why those felt different than other comics, and why those worked in a way that a lot of other comics didn’t. And so I kind of slowly but surely started to experiment with writing short things, and one of the first things I ever wrote was a short for Millarworld [specifically Millarworld Annual 2016]. Mark Millar was doing, like, a talent hunt for new artists and writers, and I sent a five-page story, and it won the first year they were doing that. So that was my first published work in 2015, 2016. And from there it felt like, okay, there’s a real chance that I could do this.

I don’t think I’ve ever said this before, but one of the first things that made me feel like I could be a writer was that I had struck up an email correspondence with the writer China Miéville, who at the time was writing a comic book called Dial H, which was one of my favorites. And while we were talking, I had made some kind of off-the-cuff joke with some character ideas, and he asked seriously if he could take them and use them in a future comic. And that kind of made me feel like, wow, I have maybe something interesting to offer. And one of the first things I made ended up being my first longform comic, which was called Maxwell’s Demons [Vault Comics, 2017; art by Vittorio Astone], and that’s where [Aditya] and I started working together, as a matter of fact.

Over to you, then, Aditya. What’s the genesis of your working in comics?

Bidikar: Well, like a lot of American kids, I would read a lot of comics, but because I lived in India, we would get these in dribs and drabs. So I read a lost of Asterix and Tintin, and other than that I would read, like, I don’t know, issue #36 of ROM: Spaceknight. I was very aware of superheroes as a kid, but not really anything else in comics. Then I did get into Indian comics as well, but Indian comics were basically entirely ripoffs of, like, old DC storylines. So you would have, essentially, somebody who is like Starro taking over a circus, and stuff like that.

Other than that, I used to read a lot of literary classics, like Charles Dickens and stuff like that, because that’s what was there in the school library. So I never really connected those two things [classic novels and comics] as existing in the same space. So by the time I was 12 I wanted to be a writer, but for me, being a writer meant writing horror stories or literary fiction, or something like that.

And then I think when I was 18 or 19, I used to religiously go to the British Council Library here in Pune, and in a magazine called Sight and Sound, a film magazine, I suddenly came across an article that was basically the equivalent of “Biff! Bam! Pow! Comics Aren’t for Kids Anymore!” And I think that article mentioned Watchmen, Uncle Sam and a couple of other things. But essentially what I did was I took a piece of paper and made a list, because from the description it looked like these are the kind of stories that I’ve been reading elsewhere, but suddenly somebody’s doing them in comics now. So I think that was my moment of conversion; I immediately realized that I wanted to make comics.

So I got into comics as a writer, and I started finding artists to draw [my comics], and we would start making these five, six-page issues, and I would letter them myself. I would just use, like, Photoshop, and kind of cobble something together. And I remember it was a writer, Tony Lee, who wrote a lot of Doctor Who comics and other stuff - we hung out, and I very timidly showed him this one comic that I had made. And he was like, “Okay, your writing is fine, although you need to edit because you’re not realizing that this is visual storytelling. But what have done with the lettering here? Like, why have you just pasted it on the text, at the top of every panel? If you move the caption box here, and you kind of move the next one a little higher up, you’ll have this flow through the panels.”

And suddenly, something kind of clicked in my mind, and I was like, oh, this is interesting. Because before that, I thought of comics as something I can write, but this [the lettering] is arbitrating the storytelling. This is actually defining how a comic book is read. And I can actually imagine myself doing it because it’s a storytelling device, not a visual device. And I think I’ve developed my visual design sense quite a lot since then, but I primarily saw lettering as a part of writing, essentially.

Let’s talk about 20th Century Men. What was the basis of the story, and with whom did it actually start?

Camp: I guess technically it started with me, in the sense that I came up with the general idea of this setting and the characters. I’ve always been interested in superheroes, but I wanted to do them in a different way, a more interesting that that kind of reflected how I see the world. I wanted to do a complicated book that was as ambitious as some of my favorite comics from the '80s. I did look at Alan Moore’s work, and Grant Morrison’s work, and I knew I wanted to do something that was as expansive; that felt as big and as small and intimate as those works did.

So I started with the Soviet Iron Man character [Petar Platonov], and that character became a critique of, first, the character of Iron Man, and then as I developed the voice, more of a critique of modern imperialism in general. And then all of these characters started to present themselves, especially as Stipan and I were talking about the project, and he was designing them on the fly. We would get on Twitter DMs, and I would describe my thoughts for a character, and then he would draw the character right there, and then the character would become much clearer.

And as we kept talking about it, I think a lot of his experiences and my experiences were going into the work, and I knew I wanted it to become a book about different perspectives - I wanted it to become a book about how this one large event could be seen and experienced by different people. And, especially, seeing the way Stipan was chaning his style and his approach for every scene depending on the character and the location only further assured that we could do this in a different, interesting way, where each character had their own perspective on the events. And each of those perspectives was sympathetic and true for them, and taken individually were, I hope, compelling and truthful. But taken all together, you got kind of a different story, and a more complete view of things.

And I wish I could say that was my plan originally. That’s really something that came about as much by my fellow creators as anything I came up with.

So how early in that development process did you approach Stipan about working on it?

Camp: Oh, minutes. I mean, I approached him with almost nothing other than the concept of an inverted or deconstructionist version of an Iron Man character during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

So the Russian perspective was a very early element of it?

Camp: Specifically the Soviet perspective. Stipan and I both have certain sympathies for socialism, I think. My father is a socialist, and was a member of the Communist Party. And Stipan grew up in a country that no longer exists, but that was famously socialist and Communist. So the Soviet Union was a very interesting thing for me, because up until the '80s, it was really an industrialized society that had a completely different way of looking at the world than the west. And you don’t see that with globalization: you don’t see that in China today, or Russia today, for that matter. There’s a certain homogenization of what the world is.

So I’ve always been interested, especially right after the fall of the Soviet Union, people [couldn’t] understand how they can have no food, but there are people with billions of dollars that have such incredible wealth. It doesn’t make sense to them; it literally doesn’t go together in their heads. It’s an almost alien way of looking at the world for an American in the 2000s. So my mother’s from the Philippines, and my father’s Turkish, and I grew up traveling quite a lot, seeing the way different people interpret things very differently, and live very different kind of lives. You know, my mother and father argued quite a lot because they didn’t really understand each other, and they had different expectations, and different interpretations of each other’s behavior. So it started from a fascination with this mentality and this ideology, and kind of developed from there.

Bidikar: Yeah, you’ve had an interest in Russian life for a while. We did one more pitch that didn’t actually happen - I won’t go into it, but it was about, like, crime and Soviet Russia, essentially. So this is not new for Deniz.

Camp: I’ve read a lot, because it is, to me, just fascinating the different ways that people can think of the world; how malleable the things that we think of as constant are. I think there are certain things that we as westerners, or really anyone that’s been touched by neoliberal globalism, think of as the way that it’s always been. Like, I can’t imagine a world without a credit score. That’s just one of the things where capitalism has become totalizing: it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine a world without capitalism, right?

But in the Soviet Union, it was a world without capitalism that was in every way modern in the way that the United States was modern. And I think in a lot of ways, 20th Century Men is about competing visions of the world - competing designs for the world. And that plays out a lot of different ways in the narrative.

Were there particular influences that went into that, in terms of either nonfiction and history, or fictional works that you drew from as inspirations?

Camp: Absolutely. This is by far the most research I’ve ever done for a project. I wanted to make sure I got a lot of the details right from every perspective. It was easy to do the American stuff, but to get the Soviet stuff right, and to make it feel like the references were references [the characters] would understand, and to map those onto real history-- but also the perspective of the Afghan people: how do they perceive things, and what’s the structure of their thought? It’s kind of a lifetime of reading that’s gone into this book. I think the structure-- I’ve seen people speculate that there’s a kind of Tolstoy, War and Peace thing that was not intentional…

I think that was my speculation that may have metastasized…

Camp: No, but I love that. I mean, when we were promoting it, we were calling it Apocalypse Now with superheroes, but just as good would have been "War and Peace and Robots".

I’m glad you said Apocalypse Now, though, because I was going to say at some point in this conversation that the very first and then the very last image of the book seems very reminiscent of Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography in that movie.

Camp: Apocalypse Now was an influence for me, but for Stipan, I don’t think that was an intentional influence until afterwards. I remember there’s a splash page in the first issue, and I was like, that splash page for some reason reminds me of Apocalypse Now. And then he looked it up, and it turned out to be very similar to a poster of Apocalypse Now. But it was not intentional, I think.

Morian: I know what page you are talking about. I was skiing then, and I was in some rented room with one pen and one sheet of paper. And I drew the page without references, without any idea what I was doing. It was just the accident; it wasn’t planned. We were just jamming: I think the first three pages [of issue #1] I did in the first 24 hours when we started, like, ok, let’s go now. We started at 8:00 [one night], and I sent him something at 10:00, like, “Yeah, what do you say? We go here, we go this way…” You know, we were talking hours and hours about what’s going on, what is this story about, what about the emotions, what does it mean to be this man?

We share a lot of experience because we are, like, Mediterraneans. You know, I grew up in a country that was in a non-aligned movement, something that nobody remembers anymore. There was a movement that was a third option: not the western option, and not the Russian option. Because they were both terrible ideas, and people that were caught between those lines had this idea that there was a dignity and pride in that movement. It was a beautiful thing. I remember that students were coming [to Yugoslavia] from all over the world because this was an open society: this was the society of the non-aligned movement.

It actually strikes me that all three of you come either directly or slightly indirectly from backgrounds that are right on the neutral fringe of Soviet society, whether it’s Yugoslavia, or Turkey, or India. These are three neutral countries poised between the two Cold War factions. And that’s a really interesting perspective to come at this story from on all three of your parts.

Bidikar: Yeah, Deniz, his family frames Asia - his father is from Turkey and his mother is from the Philippines, and between them is Asia. And we [India] are one of the few countries that actually had the word “socialist” in our constitution for a long time, until it was removed. There are areas of India that were governed by socialists - there still are. It looks a little different from the Russian Communist Party.

Stipan, how did you decide on the approach for how you were going to draw this series, particularly because you were going to need to juggle at least three different narrative perspectives in a broad sense, and then many, many more within each of those national viewpoints?

Morian: What we were saying all the time is that the story is the most important thing. Everything was about emotion, and I was trying in every way to give what I thought was needed in that moment. I wasn’t really looking at a way to present myself and show my style, and show this and that, you know? So I would try the craziest things: there are digital pages, there are pages that are really big - I mean, Hal Foster big, like huge, you know? And there are pages that are tiny: I was drawing on pieces of paper. I was trying everything, just to get in touch with the story, to bring the message across. It wasn’t easy. He is demanding a lot, because there’s layers in this story. It was really difficult, but we were spending a ton of time talking.

Camp: And also, clarity. One thing that Stipan is obsessed with, and I think what saved the book in a lot of ways because it is so chaotic, was Stipan was really focused on making sure everything can be read at a glance without the text. That everything is clear, and that people can understand it like a silent movie: if a silent movie doesn’t work, you can’t save it with captions. The images have to work.

I’m interested specifically in the question of differentiating those different storytelling perspectives, because there is a very different look to each of them. So you obviously had strategies for how to set each of these different emotional or narrative viewpoints apart from each other.

Camp: Not to speak for Stipan, but it wasn’t that you had a grant plan of how this person is going to look, or that each section is going to look like this. It’s more that you read each thing as it came to you, saw what it inspired in you, and then drew, is that right?

Morian: Yeah, yeah.

Camp: It was not like had had a ton of theoretical conversations. We talked a lot about story, a lot about the characters, a lot about the emotions. But it was very fluid. We were really letting the narrative talk to us. And even I was letting his art talk to me in deciding what the ultimate narrative decision would be.

Morian: On some pages we have, like, six pages of explanation [in the script], and we talked about it for about 10 hours. Since the beginning when we started to do this thing, we agreed that we were going to let it flow in a way that I’m not going be slavish about the number of panels, or number of pages. I’m changing where I’m putting the camera, and putting the lights, and putting the actors. And he’s giving me the substance, the most important thing, and he did it wonderfully. And he was very forgiving for me constantly trying to make it like an action movie - because, you know, I was always trying to make it - okay, now some action. [Laughs]

Camp: But that back-and-forth was the most important thing, because it was me writing, us talking about it, and then me writing something and giving it him. Then us talking more about it as he did it, then him giving me something that was sometimes almost identical to what I said, and sometimes very different, but was always a better way to get at the thing I was trying to get at. So then, each time he gave me new pages, I had to go back and essentially rewrite the script I had from scratch.

Before I probe into that, I do want to bring Aditya into this to talk, first, about how you were approached for this project to begin with, and then how you decided you were going to take on lettering a work like this?

Bidikar: Yeah, because the question you asked Stipan about systematization, actually, I think Deniz and I did a lot more in lettering. I remember I did not know anything about this book until Deniz sent me two seuqences to work on: “This is a book called 20th Century Men. It’s got a Soviet Iron Man, and Captain America is essentially the [U.S.] President.” And that’s it; that’s all I knew about it. And I was like, okay, I know how Deniz would write this - I know what approach he’s going to take. And he sent me two sequences: one was the first Vietnam sequence, and the second was the sequence where Petar’s heart gets stolen, and he was just, like, “Okay, see what you think.”

And I just kind of improvised lettering them. My approach to lettering is always that there needs to be one uniform element that takes you through the story, that you break only when necessary, in extreme circumstances. So that, for me, in 20th Century Men, was the main body font, because I realized that if Stipan’s going to draw each sequence as it comes to him, then I need an improvisational approach to lettering, but let me keep the font the same. And then I sent that to Deniz and I said I’ll keep improvising on every sequence that Stipan sends me until I feel I can’t do it anymore.

So every sequence, every time period, is lettered in a different style, but the font is the same. And what I realized when I got to issue #2 was that some periods are repeating, so I can use the same style for them. And when Stipan uses a different style for something that is happening in an existing period, my lettering style can ground that: can tell you that this is still happening in the same period, even though it looks different. Because in that case, it might be a little disorienting, because Deniz was not doing timestamps on everything, or anything like that, so you don’t always know when you are or where you are. So essentially, I was playing stabilizer. But I think I still ended up doing something like 12 different styles, and 4 major styles for major time periods. It was a delight. I mean, I think that was kind of the reason I took on the job: this has to be interesting in some way, right?

The things that helped delineate the shifting of timelines, I think, are the letters and the colors, more than any text on the page.

Bidikar: Absolutely. And I did not have an outline before we started this book, because I read those two sequences, and I messaged Deniz to say that this is the best thing you’ve ever written, I want to letter this, and please don’t let me know what happens. [Laughs] Because I want to read this as I work on it. So I think I knew one sequence in issue #6 or something, but everything else kind of came as a surprise. Everything else, I would react to the page as I saw it.

So, for example, there’s a sequence in issue #5 where we go back to the utopian land, and I was like, you know what? The art style here, there’s a lot of thunder. There’s a lot of superhero reaction. So this slightly reminds me of Walt Simonson’s artwork - it has a very ‘80s vibe.” So I just went and did a John Workman on that. It was things like that: I would be referring to where this sequence would fall into comics history, and how I might approach it like that. And the Vietnam sequence was the one thing where I actually gave it, like, an underground comic-y style, and then I looked at it and I’m like, I don’t like that. Let me do something completely out of left field. Because what Stipan’s doing is very grungy, very organic, and no lines but white and color. And I’m like, let me just do something like that instead.

So, by the time individual issue started getting crafted, how thoroughly, Deniz, had you mapped out where this was all going to go?

Camp: Not thoroughly at all. I had thought about it a lot, but how many decisions had I made? Not that many. Because I was responding to the work, and I was responding to the characters. So I cannot tell you how many notebooks full of possible endings or scenes that didn’t make it in I have. This house is just littered with them. We knew the ending; we knew that it was not going to end in a Hollywood happy ending. But there were always a thousand different possibilities for exactly how we were going to do it.

I wanted it to be responding to the work. And that was kind of the watchword for the book: we were all responding to each other. The writing has to change when I see the art, and the writing has to change again when I see the lettering. So, Aditya will often say, “You’re going to have to cut this. It doesn’t fit. It technically might fit, but it wouldn’t fit in a nice way, so it needs to be cut.” And ultimately, I think that’s part of the magic of the book: it feels like it was made by one person more than most [collaborative] comics, because everything, everything was right up to the line. And I think there’s a sense of inevitability to it, because the characters weren’t following some grand plan. The events that preceded informed the events that came next in a very visceral way. And not just the events, but the emotions that they felt during those events.

That’s a remarkable thing to hear, because on the one hand, it does feel like a very collaborative book, but on the other hand, it also feels extremely intricate. And I don’t think that most readers would think that this was something where you didn’t know where it was going before you started out.

Camp: You do a lot of thinking. There was a lot of stuff that I thought about, but didn’t know it was going to happen exactly this way. I did not have a strong outline: up until the last issue, I wasn’t exactly sure how it was going to go. I wanted to be responding to the work at all times. And that doesn’t mean you don’t do a lot of thinking, because I did a ton of planning, a ton of thinking, but a lot of that planning and thinking ends up getting chucked at the last minute.

Morian: There is, like, another 200 pages that didn’t make it into this story. He told me he was sending me everything written, and we had to make it 40 pages [per issue]. But we had 80 for every episode, easily. We were making scenes and throwing them out because they couldn’t make it into that episode. And I can’t wait to continue this story.

21st Century Men.

Camp: Exactly. I feel that the stuff that gets written and doesn’t make it in still somehow does make it in. [Like Hemingway’s] glacier theory.

Bidikar: That’s what I was going to say. Because when we were making Little Bird [Image, 2019; written by Darcy Van Poelgeest, drawn by Ian Bertram], I had this conversation with Darcy, because he would also put a lot of stuff on the page and then take it out. And he would tell me about scenes that were happening between other scenes. And the thing is, that work does show, because the reader will realize there are little details - there are things that people are doing which the reader will feel like there’s a whole world going on here. They don’t necessarily know everything that’s happened there, but it’s there, and you know.

Let’s talk about the actual collaborative process between the three of you. Deniz, you said earlier you started with a sort of sketch of what the issue was going to be before it turned into a full script. So from there, were you doing Zoom calls? How were you helping each other to flesh these ideas out?

Camp: I’ve done some Zoom calls with both of them, but I think [it was] a lot of online chatting with text. We would talk about things: I would describe roughly each scene that was going to be in the book, and then Stipan would interrogate me about, “Well, what does it mean and why?” And those questions helped clarify those scenes, you know? And then I would go and write-- generally, it wasn’t always like this, but often I would write a full script, with some scenes more detailed than others, but generally a full script that was complete.

And then I would send that to Stipan, and then he would respond, and we would talk more about it, and continue to talk about it, and he would kind of take this as his starting point and from that make something fundamentally new, in my opinion. Understanding what my aims were, but having different ideas and better ideas about how to get there. And then he would send the pages back, usually scene by scene - every page individually, just to be like, “Check this out.” And once they were all together, I would go in and basically rewrite so that I felt [the script] fit the art. I put aside the original script like it didn’t exist, and I only knew what was in my head previously.

Morian: And I’ll say again, I’m so grateful, because this guy [Deniz], he’s so good, I couldn’t believe it. I drew the pages, and when he made the final text, he makes me cry, because he elevates everything to the best it can be.

Camp: So I think, to sum it up, it was very much a game up one-upmanship, and adjusting to whatever came our way. A lot of improvisation, a lot of taking what the person did and what the person before them did, and trying to just make it better. Trying to enhance it, to keep in mind that we’re not working at cross-purposes. We’re all working toward the same place, and it’s just about figuring out the best way to get there together. And I think that if there’s a kind of special sauce, or if there’s a reason this book feels different to a lot of other books [I’ve worked on], one of the main reasons is that there’s just a ton of back-and-forth, and a lot of leaving our previous expectations to the side, and just focusing on the work itself and what’s in front of us - trying to make it as good as we can.

One thing I noticed in reading the series is that it almost seems like every issue is sort of a piece in itself in terms of narrative strategy and storytelling technique. And I’m wondering if that was something you were all aware of. And, if so, whether it was something came out of that process of collaboration.

Camp: For me, it’s just a matter of what my interests are. I try to challenge myself with a number of things. One, I feel that if you’re making comics, you have to respect the way that they’re coming out. And if they’re coming out as single issues, I want to make sure each of those single issues is satisfying, and a kind of work of art unto itself. That’s just my own personal preference. So I wanted each issue to feel pretty distinct, and to have a kind of structure to it. Some of my favorite TV shows are things like The Sopranos, or Deadwood, or Mad Men, where each individual episode has its own beginning, middle and end. Sometimes it has an experimental thing, or sometimes there’s a rise and a fall. You can feel the structure there. So that was really important to me.

And, just as a creator, I get bored, you know? I get bored as a reader, and I get bored as a writer, and I wanted to not be bored. And part of that was trying something new every time. A lot of my other work has been standalone issues, and this was something that you could argue was my first big, intricate thing. But I wanted to keep some of that excitement of the new, that each issue you don’t know what’s going to happen next, even though it’s all part of the same thing.

I hope your expectations are subverted, and there’s only so much I can do with a plot to completely subvert your expectations. But I can do a lot with the way that we’re communicating the story. And I think I challenge myself to kind of reinvent the wheel each time. I don’t know if I challenged my collaborators, but they challenged themselves to do the same. And I think, or hope, that it is all of a piece, I also hope that each new scene, each new installment, has a lot of surprise there.

So why Afghanistan as the crux of the story? Because the story, over and over again, returns to Afghanistan as the center of the narrative, and the place and the people on which this entire story ultimately hinges, and whose lens it’s filtered through.

Camp: I knew I wanted to ground the story in the real world, and I wanted it to be a story of one of the great superpowers exerting its will on some other, less powerful, less influential country. And a lot of the stuff that we’re talking about is stuff that recurs. All this stuff is cyclical. So a lot of the stuff in 20th Century Men was me as much commenting on America’s occupation of Afghanistan as it was the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. But I didn’t want it to be something modern, because people come to modern stuff with all their preconceived ideas, and notions, and feelings about things. But I think by setting it in the past, it gave us a freedom to talk about things that are equally relevant today, but in a way that maybe has people trip over it a little bit less, especially modern American readers.

And that cyclical, recurring aspect is something you bring out explicitly in issue #6, which is really about the way that history is an almost mythical cycle repeating in any era.

Camp: Yeah, exactly. I hope there’s a sense of timelessness to the story; even though it’s set in a very specific time, that specificity becomes weirdly universal.

And why Afghanistan?

Camp: I mean, Afghanistan has been the center of the world at various times, and has, for my lifetime, been war-torn and absolutely devastated by what they would call the western powers. So it was a crucial place in world history, and as is so often the case in my lifetime, these places that were once vibrant, and developing on their own, and safe, and wonderful - they’re so quickly turned into something else.

You know, when I was in Turkey when I was younger, I visited Syria, and it was then a totally normal place to be. It was lovely. The life was absolutely normal there. And I was shocked by how quickly everything changed at the beginning of the civil war. And refugees were streaming into Istanbul, and I would talk to them, and it’s just amazing how these people who were living lives just like mine five years ago had lost everything. And everyone that they knew was dead. Everything that they owned: gone, destroyed. And it was something that I felt I wanted to talk about.

And the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was one of the earlier focal points for all these powers that let me talk about the Soviet Union, and let me talk about America, and let me talk about even Great Britain - and let me talk about Afghanistan, fundamentally.

So in a way, Afghanistan in the story stands for all of the colonized peoples opposed to imperial colonizers.

Camp: Yeah. I mean, in that sense of specificity hopefully turning into universality. The history of Afghanistan is the history of Afghanistan; it’s not the history of Syria. So I did my best to represent the history and culture of Afghanistan as a specific thing, in a specific time and place, and the people there as real people. But, yes, certainly my hope is that by being truthful to that experience, and being truthful to that history, we’ve touched on something that’s bigger than that.

The Soviet occupation period for Afghanistan obviously occupies a pivotal moment in Soviet history, and I assume that each of the three of you must have had some personal perspective on that coming into this project. So what did that period represent to you on a personal level?

Camp: The thing about the Soviet-Afghanistan war is that, as an American, I didn’t know much about it. My main understanding of the Soviet Union was when I was five or six years old, we went to a furniture store, and they had an old globe there, and on the globe was the Soviet Union. And I pointed it out to my dad, because I really liked globes at the time, and he goes, “Oh, that’s the Soviet Union. This must be an old globe, it doesn’t exist anymore.” And it was this giant section of the globe - it doesn’t exist anymore? It blew my mind.

So in the United States, a lot of this stuff has been erased. I had honestly no strong impression of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. I would defy you to find an American who does have a strong opinion of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan under 50. It just was not a huge part of my life. But it was terrible: all this terrible suffering and incredible horror has been largely forgotten or ignored by the west, and by the privileged few. But of course it had a huge impact on Russia - some say it precipitated the end of the Soviet Union. It certainly led to a huge new population of veterans who had lost limbs, and were coming back with trauma. So, again, there’s a specificity to these things, but it’s universal. We can talk about the United States going to Afghanistan, we can talk about the United States going to Vietnam. But in terms of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, it’s something I really learned a lot about in the course of researching this book.

Any works in particular that went into that research that you can think of?

Camp: Oh, yeah, for sure. There’s a book called The Hidden War [by Artyom Borovik] which is by a Soviet journalist. It’s his experiences going through Afghanistan, and actually the character of Krylov is based off of him. I read the entire summation of the war by the Soviet general staff. I’ve read too many things to go into, but The Hidden War, there’s a couple of anecdotes that are taken directly from there, and, you know, made a little bit more fantastic.

But so much of the book is based in reality. The details you hear from people on the ground, like how the Soviet soldiers would boil the cartridges of AKs and sell them to the Mujahideen, so they wouldn’t work, but they would get money for their families back home. I think I have a pretty good imagination, but there’s nothing like reality to inspire you.

Stipan, let’s talk about the way you approached some of those wartime battle sequences. What were you drawing from there - was it movies, was it other comics?

Morian: I’ve seen war up close and personal because I’m coming from Sarajevo in Bosnia, which was the center of a very brutal war for a few years. I came here as a refugee with one plastic bag; was working in refugee camps for years, working with children doing art projects. But it was a way they could speak to me, because I was 20 years old, so I was kind of like an older brother, and they were children without parents. Because the parents were in Bosnia, caught up in the war.

I’ve seen war, and war is disgusting, you know? And so I was drawing from things that I saw. I’ve seen dead people. I can break and put together a Kalashnikov with my eyes closed, even now I bet, in under one minute. I don’t know what to tell you, I’m an old man - older than I appear to be.

Was it difficult, then, to draw on something that was obviously taking from a lot of your personal experiences?

Morian: No, it’s long ago. It was a lifetime ago. It was the ‘90s, and it’s far behind us. But I have this memory, when we were growing up in a socialist country. We had red stars on our hats, and red scarves, like North Korean kids. We were listening to Communist propaganda, and we knew the duplicity of the system. We knew how fake everything was. And after that, when I came to Croatia, I was looking at the brutal Wild West of democracy. It’s a “democracy” - it’s capitalism of one party that sells out the country for corruption. Everything becomes private; the shipyards are sold for, like, $1.

So what can I say? I’m deeply disappointed in the solutions that the west is offering. And I know the east, and I know the Soviet Union… so I don’t know. I’m waiting for some third solution that we need to see. What we need to see is some other sort of socialism: not Chinese, not Russian. Let’s start to change this, because this is going nowhere. We are going straight to hell.

Bidikar: That is the coolest answer to a question ever.

Well, Aditya, I’m wondering how you approached this as well, because in terms of the layouts of the pages, you’re obviously managing quite a lot of text - because it’s not a text-light book, I think you’ll all agree.

Bidikar: I think issues #4 and #6 had some kind of specific solution to them, where I actually had to sit down and be like, okay, clearly some of the storytelling is going to be in my hands on this. This is what Stipan’s doing, this is what the script is doing, and I have to make sure both of them are respected. Those issues took longer and were more of a challenge.

In issue #4, that’s because it’s built around these fictional excerpts from histories and government documents.

Bidikar: Yeah, and I think Deniz wrote most of them after the art had come in. And the thing is, the way Deniz and I work, there are times when I am a bit of a de facto editor, where there are scripts where Deniz has written, like, three different options for dialogue in three different colors. And he’s just, like, “Oh, you choose.”

Camp: That’s absolutely true.

Bidikar: Or there will be 75 words in a panel, and I can see that only 40 will fit, so I will make a call which 40 to fit in, and will just write it, like: “Okay, Deniz, I edited this, let me know if you don’t like it.” So I knew with issue #4, if there were times when I had to ask Deniz to rewrite something, he would do that. I knew I had that luxury, so it was more interesting to actually be surprised [by the script], because, it might sound like a brag, but at this point, most standard comic lettering doesn’t come as a challenge. I generally know exactly what to do. So sometimes it’s more fun to be confronted with something where I don’t know what to do, like with these two issues.

It’s just the fact that I have a collaborative relationship with my co-creators, where there were times I would tell Deniz to tell Stipan that the way Stipan’s used this space, I see what you guys were trying to do, but I can’t do anything with this. There were only a few times where I said, you know what? WE need to either have Stipan redraw something here, or Deniz needs to drastically rewrite this page.

So were there pages that were, in fact, redrawn as a result of that?

Bidikar: Yeah, there was one page, one spread, where it was actually something like a six-hour argument.

Camp: We had a great, lovely, heated argument. It was fantastic. The other thing is, Aditya and I, when we argue, we argue in a very similar manner: we’re not afraid to really go for it, but without hurt feelings.

Bidikar: There was a point at which I said, “Deniz, as much as you would like to convince me of this, you are wrong. And you’ll find out when you publish this.” So there was one page where I couldn’t figure out which panels are supposed to go first - and it was a beautiful page, but I think the art was fine by itself, and the writing was fine by itself, but when they came together [it just didn’t work]. So I actually reorganized the panels in Photoshop, and sent them back to them, and said, here’s what I think. And then Deniz and Stipan went away, and they came up with an even better solution, that was even more interesting and dynamic, and did the exact things that I wanted to do. So I love people who enable me in that. Nobody in this project said, like, “You’re a letterer; stick to what you do.” So that’s nice to have.

Camp: The beauty of comics for me is that everybody has not just their skillset, but also skillsets outside of the thing that they’re practicing. Aditya has been an editor before; he says he’s a de facto editor, but he was actually an editor, and he didn’t mention that. So we’re all coming together, and we’re going in the same direction, but we all have different experiences and different skills. And we make up for each other’s weaknesses and combine our strengths, which is the delight of comics.

Bidikar: I think on any other project, I might have pushed back, like, you guys should have planned this thing. But because I knew the nature of the project from the beginning, because I knew how they were creating it, I felt obligated to work the same way, where I need to bring new ideas where I can, and I can’t complain. If I crave a difficult and challenging project, I can’t complain when it’s difficult and challenging, you know? So it’s actually something I ended up relishing.

You can take the barest bones of scripts where the writer has only written, “Here’s what happens,” and then artists can make specific choices about how things happen in each panel that deepen the comic. A threadbare script can lead to a great comic because somebody along the way decided, “I’m going to make choices that deepen what we are trying to do.” And the thing that I bring to the table as a letterer in general, or on this project, is that I will continually make choices, and I can defend those choices. I can tell you why this is going to make your story better and deeper, and add another dimension to it. Which is partly where issue #4 comes in, where there’s a simple mode to do that, and there’s a difficult mode to do that, and which do you choose?

I want to stay with issue #4 for a moment, because I’m curious where the idea of that issue came from. Narratively, it might be the most interesting issue of the series, assembling the story out of these excerpts of fictional narratives that collectively tell the story of this history and society. At what point did this crystalize with you as the way you wanted to tell the story?

Camp: It came from me banging my head against a wall for a long time. I knew I wanted the battle to feel grandiose, and I wanted it to feel historical in the way that Tolstoy feels historical. And the thing is, I don’t have the voice that Tolstoy does. I don’t have the authority - I mean, I’m not going to start a cult, as much as I’d like to. [Laughs] So I thought about doing a third-person omniscient [narration], and it just wasn’t there. And I thought about doing it from all the different characters’ perspectives, and all of those felt small, and limited, and wrong, like I wasn’t doing justice to the full experience of it.

And ultimately what I landed on was the technique that you saw, which was pulling from documents that would interpolate throughout the issue to give a bunch of different perspectives, often retrospectively, on the battle. I was inspired mostly by Lincoln in the Bardo for that: George Saunders did something similar in prose. But in comics, I knew that having the images would add yet another layer of the story, because there would be all these different perspectives describing the thing retrospectively, but then there would be the actual story in images that Stipan was drawing.

So I felt that gave the kind of world-historical feeling that I wanted to that particular issue. It made it feel like it was something huge and important, which I think it was for the people involved. And then it became a matter of, well, how can we do this? And everybody had to do their part to make it work, because that’s conception, but conception is relatively easy. So from my perspective, it became about hammering out with Stipan a clear visual line of action, because there was so much text that was going to sometimes obfuscate and sometimes contradict each other. It became super-important that the action was very clear, and that we had a plan of battle: it had to be something that you could follow with no text at all, and get what the story was.

Morian: I would like to note here that every script Deniz wrote for this book was basically two scripts. There was one that was actually the script, and there was a supplementary document with every single thing about every single culture: he’s actually written explanations of who these people are, this is why they’re doing this, this is why they’re wearing these things.

He said, “Special forces are attacking.” And I said, what kind of special forces? And we were talking about bug men - they were, like, part bugs, part men, you know? And I came up with this-- I don’t know, do you remember The Warriors movie? These guys with baseball bats? And we started to talk about this rugby/baseball team, running at the special forces with bats, and they self-destruct.

Camp: The Suicide Cowboys.

Morian: Right: they push the button, and boom! [Mimes explosion, laughs]

Which is such a delicate thing to pull off, and I think you did it in this issue. It’s this comically satirical image, but in the context of an incredibly gruesome and serious moment in the story’s history. Which I think is something Saunders does in his novel, too, so it’s interesting to hear you bring up Lincoln in the Bardo as an influence.

Camp: Yeah, for sure. All credit to Stipan for that, really. He killed it.

Morian: This thing, you know, it’s ridiculous. We have Iron Man, Captain America, we have Godzilla, we have a British special agent that is very pompous that in no time is done, finished. It’s really absurd. But this is a serious story; it talks about important things, and important experiences. But we use shock tactics to get it across, to send a message - the craziest Road Runner schemes, you know? It’s Deniz: he gives the direction, and I supply the poison.

Camp: I’m inspired by the people that I work with. So Stipan has so much humanity in his work, and so much character in his characters, that it became clear to me that the most interesting way to do this book was going to be to focus on character: to go as deep as possible, and try to get across the full spectrum of human emotion in the book. Something we’ve talked about is that war is terrible, but it’s also funny, and there’s also incredible friendship. So for me, it was important that there were all these different feelings for you reading the book: awe, and horror, and joy, and pain. All these things were in there together.

And you know, people say it’s a very heavy book, and I acknowledge that it’s a pretty heavy book, but I make myself laugh a lot when I read it. There’s a joke in the second issue where they’re finding these weapons hidden in sheep, and he goes, “This one’s pregnant. And look at the prick on the kid!” And it makes me laugh every time. It’s such a dumb thing. But for me, it reminds me of my Turkish friends and family, with this really crude style of joke. And in issue #3, Stipan does a beautiful two-page spread of the guys sitting around a fire, and it’s just them telling dick jokes, but it feels warm and true. Some of the things that you get, when you’re reading about men at war is, “I never laughed as hard as I did in those days, because we were so happy to be alive.” And I wanted to get some of that across. But it only worked because the art was so expressive, and the lettering was so expressive.

Morian: The second issue is my favorite because it’s the episode that says the adult in the story [the scientist Egon Teller] dies, and what is left are idiots.

Camp: I see my father-- who is alive, but I see my father in this man who is disconnected from the world around him. He is unable to cross this huge distance between him and the other people. Stipan is constantly complaining that I’m not writing enough, and issue #2 had the prose pieces, and I think he likes that the best.

You mentioned wanting to approach this story through the characters, and you also said earlier that the first germ of an idea was this Iron Man figure in a Soviet context. What was it about the Iron Man archetype that you felt was worth exploring?

Camp: I find the idea of these mad geniuses with human flaws and the desire to change society, but fundamentally all their solutions are kind of poisoned because of their flaws, to be really interesting. And you haven’t been able to get that far with Tony Stark - there’s only so much you can do; these are superhero stories. But this guy’s a weapons manufacturer, which is not a superhero for me. So I wanted to take that kind of compromised person, who believes themselves to be a hero, as most people do; all the characters in this [story] believe themselves to be heroes. And it was important for me that for each individual section, when it was their turn to tell the story, there was a way that you could see that they were heroic and good people.

And so, Petar believes himself to be a good person, and believes he’s saving the world, you know, through bombs. And there’s some kind of absurdity, this inherent, sad ridiculousness, of somebody who, I think Azra puts it, “Everything he builds destroys.” And the American version of Iron Man, he’s an alcoholic, but a glamorous alcoholic, you know? And he’s handsome, and everybody loves him. And the Soviet version, I felt, would be kind of a depressing alcoholic, whose face is scarred from war and drinking.

I thought it was a visually really grotesque figure to contrast what we come to realize is an emotional vulnerability at its core.

Camp: And that visual identity for Petar is all Stipan. He was the one who made it clear that this was going to have to be somebody who’s ugly; who also, in some way, looks like a big baby, I think that was the way he put it.

Morian: Yeah, at first we were talking about Clint Eastwood, [and I was] like, no way I’m drawing Clint, but for 200 pages I’m going to draw a Frankenstein for you, and you are going to love it. And I’m so grateful, because he accepts these stupid ideas.

One of the Frankensteins from the American Revolution, no doubt. What about the idea of giving Petar this tragic relationship with Azra? Where did the character of Azra come from, and what is she to the story?

Camp: I think Azra ended up being my favorite character in the book. I think we all kind of fell in love with Azra. Azra is a representative of Afghanistan; a perspective of somebody who has to live through all of this. There’s a kind of obsession in Americans with going abroad and finding a woman who falls in love with you, and you can kind of rescue her from her circumstances. So I wanted to play with that, but I wanted this to be a more complicated, and in my opinion more truthful, vision of what that relationship is. There can be no love when there’s no equality. And I couldn’t see a way in which somebody as smart, and capable, and willful as Azra could fall in love with Petar.

But I wanted him to fall in love with her, because that’s her superpower. Again, it’s the perspective thing, where Petar sees the relationship as one thing, and Azra sees the relationship as something very different. And in time you get to see her perspective, but at first you’re kind of just left with his. And some people picked up on it even from the first issue, and others didn’t: others thought that was a more genuine love.

Because you do save the reveal, so to speak, until that incredible moment near the close of issue #5, when you give Azra a monologue that seems, to me, as close as you come to speaking directly to the reader. That feels as close as the book gets to the author’s voice talking to us, to tell us what the nature of colonialism is.

Camp: Yeah, I think that’s right. I worked very hard not to tell the reader what I think about colonialism, so I get to launder it through the characters. And I think that’s true that Azra’s perspective on things is pretty close to my own. But I think it works, because it’s her experience informing that perspective. I see now more media including marginalized perspectives, and that’s fantastic. But I see a lot of it as kind of a celebration of characters doing what they want despite the pressures of whiteness, let’s say. And that’s great, and it’s important, and it’s aspirational, but it’s not the world that I live in, and it’s not the world that the people I know live in.

So a lot of this book was [Azra] being deferential to Petar, and playing along with him, and not getting to say things that she felt. So I wanted her to be remarkable, and ambitious, and as super as any of the other characters in the book, but I wanted to do it in a different way, because I think it has to be done in a different way for it to be believable.

It seems to happen in some way or another to every character in the story that they are revealed by the end to just be one aspect of some larger social, and political, and historical system that’s always going to overwhelm them.

Camp: Yes, this is about the triumph of systems, and the way that systems grind people up, use people up, and all of them in one way or another are being used by these systems. All of them realize that they’re pretty powerless, and that whatever they do, they’re just doing the work of forces that are greater than any of them.

And I guess when I made the comparison to Tolstoy, that was what I was getting at: this idea of taking individual characters in order to gradually assemble a mosaic of history and society that’s much bigger than any of them individually can see.

Camp: Yeah, I mean, I love Tolstoy. I fully welcome that comparison. It just wasn’t a conscious choice on my part, but I think there’s a reason that there’s something true in that, and I’m happy that the story took that direction.

Morian: I don’t think that it’s most important that these characters represent the system. For me, it’s very important that they’re people. There’s a personal story regarding the [U.S.] President [the Captain America-esque figure in the story]. He’s a guy that wants to get into the action. He’s an action hero; he’s dying to get out there, and he would be happy if he could go into the field and act young again. But his personal tragedy is that he’s tied up into nothing but politics, serving his own power and the power of those around him. He never gets to step out: he is restrained, and all this force, all this power, all this strength is useless. He never gets to punch anybody. So that’s his own tragedy.

And you have Azra: her sacrifice is useless in a way. Platonov, everything he did is useless. He loses everything; he’s just endlessly defeated. They’re all defeated, in a way. It’s hard, but what happens through the years, being very close with these characters, you start to love every one of them. You know that this guy is a piece of shit, but you understand that he’s suffering in his own way.

And I think you do get the sense by the end of the book that each of the characters tangential to the core stories could have had a series of their own. You could follow them off into their own narrative, and it would be just as revealing about this world.

Morian: And that’s why I’m pestering the writer that we need to come back and do some things about World War II, and show Vietnam, and show some moments that we skipped. And we have this zombie story… there’s a ton of it that didn’t make it into the book. So I hope that we will come back again.

Camp: One of the theses of this book, and really of all my work and going forward, is that people are infinitely deep and infinitely interesting. And if you look closely enough, everybody has worth, and has a story worth telling, and is worthy, and justified, and beautiful in their own eyes. And so all of these characters, I want to have to love them, even if I’m repulsed by them. And I hope that’s what the reader feels as well, because they love themselves. So if you see them like they see themselves, then you have to love them like they love themselves.

I want to ask specifically about the closing image of the series, which is the child with a kite, shown in silhouette in front of the sun. Which is obviously an echo of the opening shot of the helicopter in front of the sun. From whom did that idea come, and at what point in the process did you come up with that image?

Camp: Stipan is the one who came up with the sun in the first issue. I loved it: I added that little line about the fields on fire, but that was just us solving a problem. We needed something for those first two pages, because the action was going to begin on the next page, and we needed the page-turn. So at the end, we had talked about wanting to do some kind of echo of the sun, and we talked about that together. So you have the ancient caravan at the beginning of issue #6, and then you have the modern caravan, which represents something like as much of salvation as they’re going to get. And I think the kite is almost paradigmatic of Afghanistan, but it really just come out of the story and the conversations.

I don’t know if this is something that you thought about, but visually, it is quite literally tied to something human and grounded: on the ground, as opposed to this totally disconnected machine that you see at the beginning of the opening issue.

Camp: Yeah, that was absolutely part of the thinking.

And Stipan, there must have been some thought about the coloring of that final issue, because much of it uses much brighter, flatter colors than you see in the more illustrative and muted style in the other issues.

Morian: Yeah, the last issue is an explosion of life. It’s about richness and beauty, because the character in the book says, “This is the place they call the graveyard of empires.” And so we made it a beautiful place. We showed the light, the colors, the vibrance and everything.

Camp: We trust the instinct. If Stipan makes a choice, there’s a reason for it, even if he can’t articulate it in the moment. I find that often in my writing, sometimes the initial impetus is subconscious. You don’t know exactly why you do it, but you realize it after the fact.

I want to ask each of you about where you’re going from here. Aditya, I know that you’ve talked before about how at this point you want to move away, or at least take a break, from lettering.

Bidikar: I’ve sort of been in semi-retirement for the last six months now. I used to call it a hiatus, but somebody pointed out that I’m still working, but just not as much as before. And I think that’s going to continue for a while. My priority right now is to recuperate, because I was suffering from a fairly bad case of burnout, both mental and physical, because you might have noticed I did a lot of work over the last four years. I’m finding that if I do fewer books, I feel more joy while doing them.

I’ve had a couple of short stories and short comics published recently, and a few more are coming. I’m working on a longform miniseries at the moment as a writer. And other than that, I’m just learning to draw, so that at some point in time I can do everything myself, and I don’t need these people. [Laughs]

What about you, Stipan? What’s next for you?

Morian: I’m drawing some steampunk thing right now. It’s a little thing; it’s like 90 pages. And then Deniz is coming here. We are going to an island away from mobile signals and from civilizations. We are going to drink wine, jump in the sea, play with my baby, and make another great story that we are already working on. Because we have just learned how to work together. I’m not approaching this project like a job. The process is beautiful; the process is the reward.

Camp: I think Stipan is almost underselling it. We have, like, the next three or four things. We’ll be working together forever, I think. For me, at least, this is like a lifetime partnership - the next two things I already have the scripts for. I think I really figured out the kind of writer I wanted to be while doing this book. The process - Stipan said it. I’ve always felt that if you want to be great at something, you have to be in love with the process of doing it, not having done it. The work is almost a byproduct of doing the work.