From The Comics Journal #129 (May 1989)

I AM NOT TERRY BEATTY’S GIRLFRIEND, Finale

TERRY BEATTY

Muscatine, IA

[Addressed to Gary Groth] I’d like to apologize for the manner in which I addressed you on the phone the other day. After reading the latest entries in your seemingly never-ending “I Am Not Terry Beatty’s Girlfriend Contest,” I simply lost my temper. I’m not proud of the fact that I allowed your prodding and poking to finally cause me to turn and snarl at you, but even the most docile of God’s creatures will attack if continually provoked. My apologies also to the contest entrant I spoke to (rather rudely) on the telephone.

I acknowledge and support your right to hold and express your opinions regarding any comic creator’s works, including my own. I do, however, find it unfortunate that comics creators are not allowed to respond to TCJ’s criticism without a vitriolic response from you and various other TCJ contributors. I must also point out that sponsoring a contest in which TCJ readers are encouraged to write sarcastic “defenses” of my comic book series Wild Dog—and in doing so, also contributing rude and personal comments regarding Wendi Lee, Max Collins, and myself—goes far beyond the boundaries of fair criticism, legitimate Journalism, and good taste. Your contest does not qualify as satire, because a) it was in fact a real contest, with a prize awarded; and b) no work of art or entertainment was being satirized, rather personalities were being ridiculed.

I also have to wonder about the motivations of people who would so gleefully take part in this pseudo-literary pie toss.

This ongoing ridicule is especially inappropriate when one considers the fact that Wendi had nothing to do with the creation of Wild Dog, and that her only "crime" was writing a letter of comment to TCJ regarding Peter Cashwell’s review of Wild Dog’s first issue. This is hardly an appropriate response to one of your readers if "Blood & Thunder" is indeed intended to be a forum for the free exchange of ideas. I feel that a public apology to Ms. Lee in the pages of TCJ would, however, be appropriate.

Gary Groth replies: I will try to refrain from being unduly vitriolic—or even misanthropic, misogynistic, or indecent for that matter—and answer Terry’s gracious letter as seriously as I can.

When I received Peter Cashwell’s review of Wild Dog, I have to admit that I didn’t give it much thought. It looked like a good put-down, written with flair and humor, of the kind of sophomoric pap that DC and Marvel trade in week in and week out as a matter of course. And since such processed junk ought to be publicly flogged periodically as a matter of principle, and since we hadn’t done so recently having been much too high-minded of late, I decided to run it. If you read the review, you’ll find that it doesn’t take the comic or itself that seriously, though it does criticize the book seriously for a moral clumsiness that shouldn’t appear even in a kid’s comic.

For reasons that I still cannot fully fathom, the review—all of two pages in the magazine and maybe 750 words in total—provoked two vigorous protestations from Terry Beatty and Wendi Lee, which arrived at the Journal offices on consecutive days.

I must admit that we thought that this was pretty ridiculous on the face of it, but then there was the actual content of the letters. Terry, for example, lectured me on how the Journal could be an “important forum on comic art” if only I didn’t run reviews such as the one on Wild Dog. I realize that Terry thinks of himself as something of a comics connoisseur as well as a critical intelligence to be reckoned with, but being lectured on the intellectual responsibilities of The Comics Journal by the artist of Wild Dog struck me as astonishingly presumptuous and hypocritical to boot. To put it bluntly, I don’t need to be lectured on how to keep my house in order by someone who lives in a shambles.

Both Terry and Wendi Lee adopted the same strategy of defending Wild Dog on the grounds that it’s wholesome junk: it’s “a straightforward, traditional costumed-hero comic book—updated for the ’80s, and packaged for the G.I. Joe crowd” (Beatty), and the character is “just a guy in a costume with a grudge.” On the other hand, Cashwell’s criticism of the book’s fuzzy morality was countered with a defense on literary grounds that would be better applied to Dostoesvky or Koestler (black humor, irony, literary subtexts, etc.).

Call me a silly goose if you must, but I thought this was all absurd, and far too absurd not to indulge my mischievous habit of tweaking Beatty’s and Lee’s thin-skinned response and the obvious circumstances that prompted them to write. The Contest was not meant, nor taken by Journal readers to be, as far as I know, an attack on Wendi Lee for being Terry’s girlfriend. Rather, it ridiculed the context. Unless someone is willing to argue that it was merely a coincidence that Wendi Lee was the only reader out of 11,000 to protest the review of Wild Dog, it is perfectly obvious that her vitriolic denunciation of the review and its motives (“reprehensible” and “disgraceful” is how she described it in her first paragraph) was dictated entirely by her relationship with Terry. If we had gotten 50 (or even a dozen) letters denouncing the review, I probably would have thought nothing of getting one from Terry’s girlfriend. As it stood, however, I found it highly improbable that if the review were truly as reprehensible and disgraceful as Wendi described it, that we would not have gotten at least one other letter saying as much. The Contest may not have been the most brilliant display of opprobrium in the history of criticism, but it was a mild rebuke, all things considered.

On a slightly more serious level, there is the matter of the comic itself and the virulent defense of it, and the appropriateness of our response. If we believe that the literary and artistic imagination makes possible the gaining of insight into the variety and fullness of comparative humanity, I believe it is incumbent to deplore that which seeks to deny this—the great volume of mediocrity that is manufactured on a mass scale and that represents an appalling waste of human intelligence, exertion, and resources on the part of the producers as well as the consumers. I realize that this is practically heretical in a country that adores junk, and that such junk represents nothing so much as business-as-usual. But there is a kind of death involved in the submissive acceptance of the cultural flotsam and jetsam that serves the interests of financial institutions and a mass economy at the expense of the collective withering of human conscience.

Terry, in one of his more cogent outbursts over the telephone, said of Wild Dog that “it’s only a comic!” This, I suppose, succinctly summarizes our philosophically irreconcilable differences. We must tolerate the great mass of rubbish because we live in what we laughingly refer to as a liberal society, but we needn’t countenance it in our public discourse; given the fact that millions of images of this junk have been produced and disseminated, and given the fatuous circumstances surrounding its defense, I think our response was appropriately amusing and civilized.

Which brings me ’round to another observation, which is that I think critical discourse in the comics profession is too fucking polite, to borrow an apt phrase I heard Christopher Hitchens use recently in a similar context. I attribute the American public’s squeamishness in the face of what Kenneth Smith correctly defines as the appropriate ad hominem critique elsewhere in this letters column to the standardization of the mass media and the vacuity of the opinions expressed therein. We cannot expect people to even accept the idea of lively forensic sparring, spirited debate, or powerfully expressed views if they have been weaned on dreary pap and a variety of opinions and perspectives that range from A to B.

I can sympathize to some extent with Terry’s resentment at not being allowed the last word in a Journal exchange. But, given the fact that the economic and artistic status quo is on Terry’s side, that every other periodical in the comics field is happy to suck up to Terry’s corporate sponsors and give him an unspoiled forum with which to vent his views, and that the Journal is the only publication that mounts an opposition to this point of view, I think we’ll retain our editorial prerogative.

In the interests of moving on, we’ll refrain from publishing Cynthia McGarvie’s letter detailing what she referred to as Terry’s “harassing phone call.”

From The Comics Journal #131 (September 1989)

I AM NOT TERRY BEATTY’S GIRLFRIEND, Encore

TERRY BEATTY

Muscatine, IA

[Addressed to Gary Groth] Since the latest installment of our letter column brouhaha [Journal #129] is headed “I AM NOT TERRY BEATTY’S GIRLFRIEND, Finale,” one might assume that you feel we are done with this particular matter. As much as I’d like that to be true (I have better things to do than argue with you), I can’t let some of the comments made in your “Editor’s Note” and reply go unchallenged.

You continue to find it outrageous that the only defensive responses you received to Peter Cashwell’s review of Wild Dog came from Wendi [Lee, Beatty’s erstwhile girlfriend] and myself. Who else should have responded? If, to make a rather crude analogy, you were to smack me in the mouth, and I were to respond by smacking you back—and if Wendi, in my defense, were to hit you over the head with an umbrella—would you be justified in being offended by all of this because nobody else took a swing at you? I can defend myself and my work quite well, thank you, and I don’t expect or need anyone else to come to my defense, though I am flattered that Wendi chose to do so.

I still question the motives of people who would so gleefully enter your “contest,” and it was my curiosity about how one of these entrants might react, if contacted by me personally, that led me to phone Ms. McGarvie. She was the only letter writer I called because she was the only one for whom directory assistance had a number. I had every intention of being polite and courteous, but being on the receiving end of an extremely condescending attitude pushed the wrong button in me and I lost my temper and blew up at her—an act for which I have already apologized in the pages of The Comics Journal. But, Gary, I did not scream at her for 10 minutes—or anything approaching 10 minutes, as you report. I was on the phone with Ms. McGarvie for no more than one minute, as the enclosed photocopy of a portion of my phone bill proves.

While the eventual tone of my call to Ms. McGarvie was rude, I did not threaten her in any manner, and my rude comments to her were hardly as insulting as her letter in Journal #127, which smugly paints a portrait of my collaborator Max Collins and myself as panderers.

Further inspection of the phone bill will show that neither did I scream at you for 10 minutes, as you claim. I spent two minutes on the phone with Kim Thompson, and, in a separate call, three minutes on the phone with you. I was curt with Kim, while informing him that I wanted my two submissions to your “Swimsuit Issue” of Amazing Heroes pulled, and my name dropped from your complimentary subscription lists for Amazing Heroes and The Comics Journal (as I can no longer, in good conscience, do any business with you, or accept any freebies from you), but I didn’t raise my voice with him at all. Sure, I yelled at you for a portion of our three-minute phone call, which I recall ended with you telling me to “fuck off” after I questioned the quality of your own writing, but that doesn’t add up to me screaming at you for 10 minutes, does it? Gosh, you get so fussy when Harlan Ellison doesn’t get his facts straight, I wonder why you don’t take care to be more accurate in your own reporting.

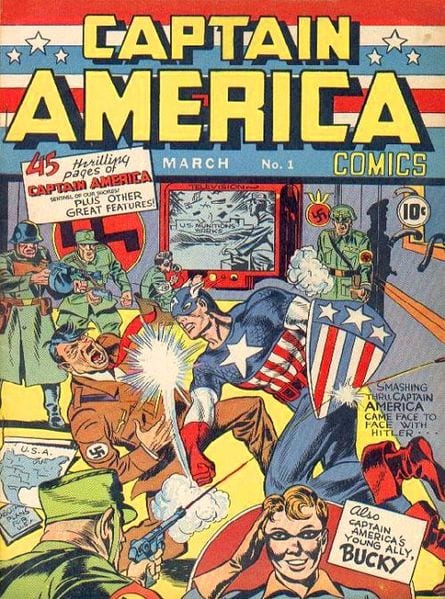

And if my super-hero comic Wild Dog represents “…the kind of sophomoric pap that Marvel and DC trade in week in and week out as a matter of course,” and if “such processed junk ought to be publicly flogged periodically as a matter of principle,” then I have to wonder why The Comics Journal was built on such “processed junk.” Or have you forgotten that the Journal used to regularly cover-feature such high-falutin’ comics as Captain Victory, Ms. Mystic, and The Teen Titans? No offense meant to any of the creators of the aforementioned books, but you sure wouldn’t put them on the cover of the Journal now, would you? No, with your “scorched earth” editorial policy, you have used up and dismissed the creators of mainstream super-hero comics now that they no longer fit into your current editorial vision of the Journal. I wonder how long it will take for you to build up and tear down the underground, newspaper, and foreign cartoonists that are your darlings of the moment.

In your personal letter to me, you refer to Wild Dog as “...a bit of hackwork... cranked out to meet some bills...”—and in your editorial comments in the Journal, you attempt to pass off Collins and Beatty as the worst sort of Marvel/DC hacks, completely ignoring the eight years we have spent working in the independent comics field, turning out 50 issues of Ms. Tree, a creation that has earned us a loyal readership, a certain amount of critical praise — and damned little financial reward.

Wild Dog was done partially to pay a few bills and underwrite my work on Ms. Tree, but it was also done because I wanted to draw a super-hero comic. I grew up on Batman, Spider-Man, and the Fantastic Four, and wanted to create something that might give today’s readers the same kind of kick I got when I was a kid haunting the newsstand waiting for the latest adventures of Superman or Nick Fury. “Hackwork” is created by people who don’t give a damn about their work or their readers, and who crank it out just to make the bucks. I’m sure that there are people like that working in comics, but I don’t know any of them. I’m not one of them and neither is Max. If he were a hack, he wouldn’t have walked away from his lucrative gig as writer of the Batman comic book over editorial disagreements, but rather would have stayed on and given ‘em what they wanted and pocketed the dough. And when exactly did it become a crime for artists and writers to earn a living from their own work?

You may find this hard to believe, Gary, but both Max and I put a lot of hard work into Wild Dog, and we both cared a great deal about the feature. In the stories that have seen print so far, we have dealt with issues such as censorship, pressure groups, hero worship (and that selfsame “moral clumsiness” that Wild Dog’s vigilante tactics represent), as well as the influx of “crack” cocaine into our communities—while at the same time having a good amount of ol’ fashioned super-hero comic book bang-up fun (the kind Dr. Thomas Radecki seems to like so much, he said sarcastically). Of course, you wouldn’t know that, because you’ve obviously not read the series, dismissing it as “dopey” and “hairbrained.” I find this particularly amusing, because if you spent less time with your thesaurus digging up words like “opprobrium” and more time with your dictionary, you’d know that the correct spelling of the word is harebrained. I really can’t be too insulted when the guy calling my work stupid can’t even spell his insults properly.

If Wild Dog displeases you or your compatriots, I’m hardly heartbroken—we didn’t make it for you. And if, as implied in your editorial so eloquently titled “Batshit,” talents such as Alfred Hitchcock, Jim Thompson, Cornell Woolrich, and Sam Fuller were unable to create works worthy of your stamp of approval, then I sincerely doubt that the works of Collins and Beatty could ever please you. Nor would we want to create anything that would. We’d prefer to remain on your list of those-who-are-unworthy, as long as that list remains as impressive as this.

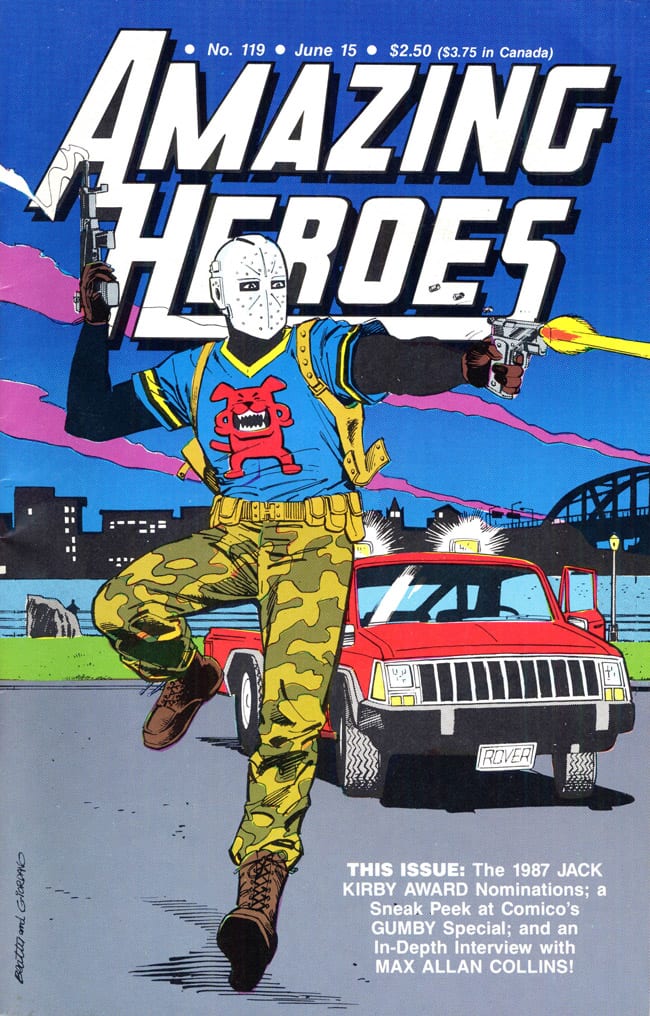

And if Wild Dog is such garbage, then why the hell was it cover-featured on the June 15, 1987, issue of your magazine Amazing Heroes? Come to think of it, what is someone with your stated opinion of super-hero comics doing publishing Amazing Heroes in the first place? Isn’t it just a tiny bit hypocritical to be so artsy-fartsy in the Journal and then give us such important features as “The Ten Best Fight Scenes” (or some such) in Amazing Heroes? Or maybe you just publish Amazing Heroes for the money. Gee, doesn’t that make you a hack?

Sure, I suppose you did us something of a favor by cover-featuring Wild Dog in Amazing Heroes. We might have sold a few extra copies of the mini-series because of that exposure, but isn’t it possible that you might have sold a few extra issues of Amazing Heroes because of Wild Dog’s cover appearance? DC did advertise the mini-series quite extensively, and Amazing Heroes #119 came out in the midst of all that. In fact, it seems to me that the comic books and cartoonists featured in the Journal and Amazing Heroes would still do just fine without that coverage—certainly Sergio Aragones, Moebius, and Bill Watterson were doing quite well for themselves before making the cover of the Journal. But without those comics and cartoonists, the Journal and Amazing Heroes would just be blank pages. It amuses me to know that the comics community could roll along just fine without your publications, but that you are dependent on the comics community for your livelihood. That’s especially amusing when one considers the contempt you display for most of us in the pages of the Journal. Has Fantagraphics ever made a dime that wasn’t somehow gotten by publishing, praising, or criticizing work done by people capable of doing something you are unable to do—create comics? You can publish ’em, Gary, (and you publish some damned good ones), but you can’t create ’em. In the words of Roald Dahl, “We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of dreams.”

Of course, there’s also the fact that as a comic book publisher yourself, you really have no business publishing criticism of books from other publishers. Since you are competing for comics shop shelf space with every other publisher out there, how can we take seriously any of your opinions regarding comics not published by Fantagraphics? I think a fairly good-sized conflict of interest exists here. The term “morally bankrupt” comes to mind.

There’s also a lack of integrity involved with the fact that the Journal reviews other Fantagraphics publications as well. I know you justify this by running the occasional less-than-glowing review of Fantagraphics product, and even a token bad review now and then—but publicity is still publicity, and by devoting space to your own books and magazines in your review columns, the Journal proves itself to be no more a serious journal on the art of comics than is Marvel Age. I also have to wonder how you would react if any other comics company were to publish a Journal-style magazine, standing in judgment of your publications, while relentlessly plugging their own.

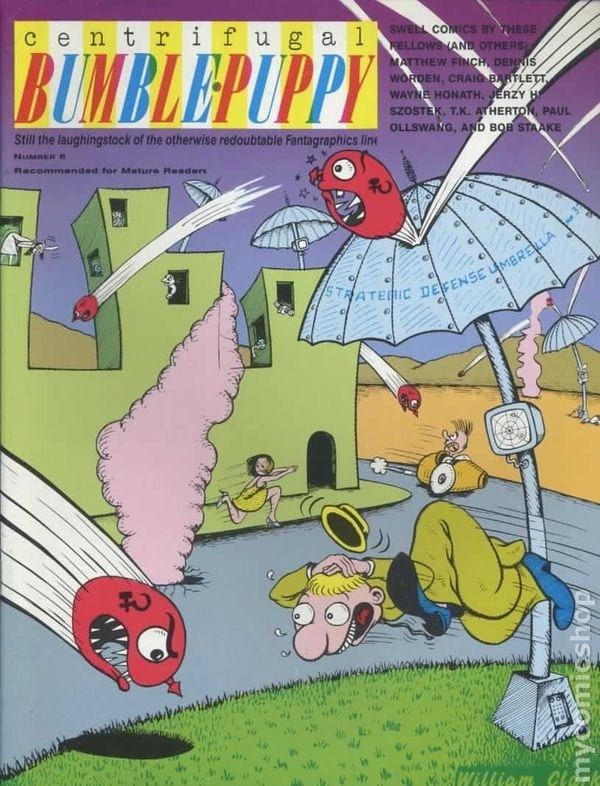

And after reading your rave-out response to Max’s letter in Journal #122 regarding his giving a deposition in the Alan Light lawsuit, how could anyone think any reviews of Collins and Beatty’s work in the Journal could possibly be fair and objective? O.K., Cashwell’s review was unsolicited, but no one held a gun to your head to make you print it. If it had been about any other costumed hero comic, would you have wasted any space on it in the Journal? Come on, Gary, let’s just admit that the Journal isn’t a serious Journal of comics criticism, but rather your forum for telling people you dislike to (as you told me on the phone) “fuck off.” I think we’d all have a good deal more respect for you if you’d at least drop the pretense. And if you don’t like being lectured to by the artist of Wild Dog, think how I feel about being judged by the publisher of Centrifugal Bumblepuppy! If my house is “a shambles,” Gary, then yours must be a federal disaster area.

You condescendingly refer to me as someone who “…thinks of himself as something of a comics connoisseur...” Actually, I’d never put it in those terms. I’m a cartoonist and a collector of comic art. I’m knowledgeable about comics, but would never paint myself as an expert. Still, I know more about comics than some Fantagraphics contributors—I at least know the names of the creators of Superman, and know the difference between Segar and Herge—and that’s more than can be said for the authors of two recent pieces in Amazing Heroes (and I’m not talking about Sidney Mellon). Certainly, there have been, and continue to be, contributors to both Amazing Heroes and the Journal who know their stuff. Amazing Heroes’ recent issues showcasing foreign and 3-D comics were excellent. R.C. Harvey’s piece on Alley Oop, Terry and the Pirates, and Alex Toth’s Zorro [Journal #129] was particularly good as well. I’d also add that Harvey’s commentary was free of the pompous nose-thumbing that far too often pervades the Journal’s editorial content.

The day I made my phone call to you, I was furious with you—furious at the unfair treatment accorded my work and my friends in the pages of the Journal. But after that uncharacteristic temper tantrum on my part (for which I did have the decency to apologize), I’ve somehow transcended those feelings of anger and frustration that were the result of your tauntings. I no longer see you as a foe worth fighting. I am reminded of the pathetic chess-club nerd quick to call all those around him “geeks” before they have a chance to label him the same, pitifully unaware of his own hypocrisy. I see the image of a playing-card king, shouting, “Off with their heads!”—a naked emperor who has built his gloomy little kingdom on the backs and the bones of those who possess talents he will never own or fully understand, a barnacle on the belly of a whale. I dismiss you, Gary, as you have dismissed so many of us. I no longer care what you think of me or what you say about me. Now go ahead, look down your nose at us and tell us why you are so utterly superior to the rest of us—do your little self-justifying song and dance.

Gary Groth replies:

While it’s true that my gloomy little kingdom has been built upon talents I do not possess, it’s also true that it’s been built on talents that Terry Beatty doesn’t possess either, which is very much to the point insofar as it was Beatty’s talent—or lack of talent—that was called into question in these pages in the first place, and which has propelled this exchange to its current level of hysteria. It has become all the more relevant because Beatty’s arrant display of egomania and indignation is legitimate only to the extent that his professed artistry, integrity, and innate superiority over those of us who do not conform to his definition of an acceptably Creative Human Being is unassailable. If Beatty is a great artist, it naturally follows that I am a barnacle on the belly of the whale of creativity, because, regardless of the quality and commitment of my publishing efforts, I had the temerity to publish criticism of Terry Beatty. I realize that every artist—indeed, every individual—must have an ego, but Beatty’s claims measured against his achievement represents an ethnocentric pathology grotesquely out of control.

Beatty claims that Wild Dog is not hackwork, that he poured his heart and soul into it. It’s not that I don’t believe him, but more’s the pity. Have standards deteriorated so much that work absent of elegance, beauty, complexity, understanding, wit, drama, maturity, or even so much as a modicum of distinction is not in fact hackwork, but work in which the creators believed deeply and passionately? In a better time, such sincerity would be seen as the amateurishness it is, but it would never see print. In our time, such sincerity becomes delusion, and such delusion becomes a professional standard.

Not only is Beatty incapable of producing hackwork, but he doesn’t know even a single hack in the comic book business. Representing the comic book industry as some sort of Creative Nirvana is pure, unadulterated bullshit, but it suits Beatty because it plays to the prejudices of the majority of working professionals and creates a false sense of solidarity and division (Beatty and the Creative Community on one side and The Comics Journal on the other). The truth is that ever since the independents forced Marvel and DC into granting rights in the form of greater financial remuneration, mainstream comics has turned into one gigantic whorehouse where so-called creators lick their lips over the possibility of writing or drawing the latest adventures of some ultra-violent, neo-fascist psychopath—which just happens to be the most popular and therefore most lucrative characters in comics today—all the while professing their commitment to the precincts of art, mind you, while figuring their take on their wristwatch calculators. I mean, who does Beatty think he’s kidding? Or is it possible that he actually believes that all this pap—well in excess of 200 comic book titles a month by my count—is turned out by dedicated artistes?

Then there’s Beatty’s nasty little definition of hacks as “people who don’t give a damn about their work or their readers, and who crank it out just to make the bucks.” Since no one is willing to come forth and declare himself a greed-crazed pig who doesn’t care a whit either for his own work or the reader, Beatty’s definition is self-fulfilling: there are no hacks in the comic book business. If that’s the case, and if Sturgeon’s Rule—that 90 percent of everything produced in the arts is crap—is as applicable to comics as to every other art in America, who are the music makers and the dreamers of dreams producing the drek that represents 90 percent of the industry’s output? Ninety percent of the comics produced, incidentally, at a conservative estimate means no less than 180 comic book titles EVERY SINGLE MONTH—or 2,160 different comic book titles a year—and yet, according to Beatty, there’s not a single hack among them! And if Wild Dog, which is every bit as bad as most and considerably worse than much hackwork of the past, is NOT hackwork, what is it?

Beatty’s definition of a hack is so absolute and restrictive that nobody could possibly qualify. But, in fact, a hack was not quite so blatantly as contemptible a creature as Beatty makes him out to be. Traditionally, throughout most of this century, a hack was someone who took a purely professional pride in serving the needs of a commercial establishment. He learned the skills of his trade—and it was a trade to him—and performed them competently. Contrary to what Beatty writes, hacks were not necessarily joyless, self-contemptuous individuals. Many Hollywood hacks enjoyed what they did and were good at it; and, much to their credit, few of them deluded themselves into believing they were music makers or dreamers of dreams.

This simple honesty toward oneself has since changed. Common-sense distinctions between entertaining hackwork and work that embodies the potentialities of genuine art are no longer made. With the rapid deterioration of standards in popular art, the increasingly sophisticated marketing techniques of economic institutions that finance the popular arts, the legitimization of pop art in the academy, and the enshrinement of philistinism as a critical standard in the popular media, the evaluative faculties necessary to discriminate between entertaining hackwork and art have evaporated, and everything is “scrutinized” with the same, critically blunt yardstick.

All of this just goes to demonstrate how useless our terminology has become in the face of the unimpeded commercialization of human values and the consequent transfiguration of mass consciousness. Clearly, there are no more hacks; nearly everyone working in the popular “arts” has accepted a priori, the infantile, commercially-imposed values of mass culture as a natural aesthetic norm. Once such values become internalized, they can be regurgitated with what passes for sincerity.

So in one sense, Beatty is right: there are no more hacks in the old sense. Obviously, we need a new term to describe members of the post-hack generation who are producing the equivalent of hackwork, but who are doing so with great and indisputable sincerity.

I propose NEO-HACK.

The neo-hack dominates our popular forms—movies, television, comic books, et al. The neo-hack consciousness has been deformed by a slippery slope of internal logic leading to or deriving from (it’s often difficult to tell which) near-idiocy. The neo-hack is characterized by a willfulness uncultivated by any values other than itself. This willfulness to, say, draw super-heroes or make action-adventure movies, or break into TV, is then transformed into a need, which is then affirmed as a belief by the ersatz sincerity of what one is doing.

The important thing to remember is that the neo-hack truly believes, on some level, in what he’s doing. The gaffer on the latest James Bond movie could very well be a neo-hack if he truly believes that the project he’s a part of is artistically worthwhile, and he could react indignantly or even violently if told that he’s working on cretinous junk.

Neo-hackwork is immediately recognizable by its slick, modernist, but essentially slavish devotion to the devices and forms of commercial art (though even this will change once the neo-hack discovers, assimilates, and debases whatever avante-garde [sic] forms come to his attention. Remember: the stylistic surface of the neo-hack changes with the times; it’s only his values that stay the same). The other essential characteristic of neo-hackwork is its consummate lack of content. The absence of content is harder and harder to prove in an age that celebrates vacuous entertainment, but is nonetheless an indispensable part of an admittedly loose definition. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, John Carpenter, John Landis, Brian DePalma: all neo-hacks. (If you want counter-examples, I’d choose Bill Forsythe, Bruce Beresford, Philip Kaufman, and Woody Allen — which is not to say that everything these four do is successful, but that they are at least artists and not neo-hacks, and should be respected as such.)

Beatty is the perfect example of a neo-hack, proclaiming his greatness at a fevered, megalomaniacal pitch while producing work that abounds in cliches, stereotypes, and formulaic patterns. Argument as to whether Beatty is an inept mediocrity who makes Jack Kamen look like a revolutionary stylist (my position) or an artist of the kind Roald Dahl referred to as one of “the music makers” and “the dreamers of dreams” (Beatty’s position) can go on ad infinitum, boring our readers nearly to death. Therefore, we’ll print as much of Beatty’s Wild Dog work as we can squeeze in here so that the reader can judge it for himself.

Since Beatty is quick to accuse me of hypocrisy, he may be interested to know what the word means (just as he may be interested to learn that “harebrained” can be spelled “hairbrained,” or so the Oxford English Dictionary tells us: “Hare-brain. Also hair-, [f. Hare sb + Brain. The –spelling hair-brain, suggesting another origin for the compound, is later, though occasional before 1600.”). Hypocrisy is defined as “the professing of virtues and beliefs that one does not possess” (American Heritage Dictionary); and unfortunately for Beatty’s indictment, I have never professed purity as one of my virtues, nor have I demanded it of anyone else. I demand only a reasonably consistent application of principle. (Naturally, the principle to which one commits himself should be morally worthwhile since a consistent commitment to deplorable principles is no virtue even though there’s no hypocrisy involved, either.)

At this point a subtle distinction should be made, which I have every confidence will sail over Beatty’s head. A compromise of principles should be judged by the severity of its deviation and its significance relative to the whole, if such judgment is to have any substantive meaning. As an example, Arthur Koestler hacked out several books in the ’30s, but to denounce him for this would be petty, foolish, and beside the point in light of his subsequent humane contributions to moral and political literature.

I have heard this same charge of hypocrisy before as regards Amazing Heroes, and it is always delivered with the self-satisfied smugness of someone faciley trying to score points but who represents the very status quo that makes such a compromise necessary in the first place. And make no mistake about it—Wild Dog and its slightly better cousin Ms. Tree represent the artistic status quo: trashy genre fiction, as predictable, one-dimensional, dull, and unimaginative as anything being done in mass entertainment today. There’s something even more contemptible about this attitude than the more typical one of eating your cake and having it too, for it takes a sanctimonious pleasure in watching brute economic forces compromise the dignity of an individual—and all in the service of scoring a cheap shot. Yes, Amazing Heroes is a compromise—as are several other books we’ve published over the years, by the way—but I am fully prepared to argue that Fantagraphics Books has been as diligently observant of the principles of economic equity and artistic excellence as many of the literary publishers outside of comics, and considerably more so than the comics publishers Beatty has worked for. Briefly, but without false modesty, I am willing to state that I believe Fantagraphics Books has served the needs and aspirations of the cartoonist, as well as the artistic, intellectual, and spiritual demands of a discriminating public, quite honorably. Considering the vigor of Beatty’s indictment, I think further comment on this point is unnecessary.

Speaking of serving the needs of cartoonists, just who are the we and the us to whom Beatty continually refers? Has he actually deluded himself into believing that he is speaking on behalf of the vast body of professional cartoonists? Or is this merely another demonstration of megalomania, the same megalomania that allows Beatty to quote Rodd Dahl’s grandiloquent line “We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of dreams,” and conclude that Dahl was referring to him. This is, of course, presumptuous and a characteristically self-serving rhetorical maneuver. We may logically infer that implicit in Dahl’s statement is the assumption of artistic or literary merit; after all, not just any music makers will do. Unless Dahl mentioned Beatty by name, I think it’s fair to assume that Dahl did not have in mind dreamers who dream up rubbish like Wild Dog.

Various other allegations, charges, indictments, impostures, and fatuities scattered throughout Beatty’s letter deserve comment.

Yes, I continue to find it ridiculous that the only two readers who responded to the review of Wild Dog were Terry Beatty and his girlfriend. More ridiculous yet is Beatty’s insistence that this is not ridiculous, and his contention that it is entirely logical, after all, that the only persons who should respond to a review are the artist and his immediate coterie (i.e. lover parents, siblings, etc.). My position has been and continues to be that Beatty has grossly overreacted to the original review, and that the proof of this is the fact that out of 13,000+ readers, only Beatty and his girlfriend were sufficiently moved to respond to the review. Furthermore, not only were they the only two to respond, but their vitriolic responses were out of all proportion to the actual critical tone of the review, which was mostly one of bemused stupefication that a book as idiotic as Wild Dog could be produced and published in the first place.

Beatty’s girlfriend called the review “reprehensible” and “disgraceful.” Beatty claims that it was mere coincidence that the only person other than himself to write a letter protesting the review was his girlfriend. This means, therefore, that only Beatty’s girlfriend had the moral sensitivity to recognize and protest a “reprehensible” and “disgraceful” criticism. No one else noticed this but her. (We may infer from this that all other Journal readers are too insensate to recognize and appropriately respond to a disgraceful, reprehensible review; their moral sensibilities have probably been numbed by repeated exposure to such vile critical atrocities in the Journal). But, with this letter, Beatty makes reference to “the unfair treatment accorded my work and my friends in the pages of the Journal." Where was Beatty’s girlfriend when Beatty’s friends were being savaged and pilloried in the pages of the Journal? May we assume from her silence that she approved of such “unfair treatment” of Beatty’s friends? God only knows; it’s all so complicated. It’ll probably take another novella-sized letter from Beatty to sort all this out.

At this point, the only proper response to Beatty’s continued claim that it was mere coincidence that he and his girlfriend were the only readers to notice the great injustice being perpetrated against his genius is, Please go away. Please take your marbles and go home. Enough is enough.

(By the way, Beatty’s umbrella-bonking analogy is wrong-headed and irrelevant. “Who else should have responded” to the review, he asks rhetorically, meaning that only family members or intimate friends should be expected to reply to criticism of an author’s work. The correct answer is: “Any reader who feels compelled to enter the public arena and discuss the critical issues brought up in the review.” One of the functions of criticism is to inspire reflection and debate on the part of the public. If criticism were as private and insular as Beatty seems to think, we d merely write letters to each other. This inability to grasp the fundamental social value of public discourse is staggering, but not surprising. As to the analogy itself, physical assault is, if I’m not mistaken, covered under various criminal statutes, and is therefore not a private matter between assailant and victim, but a public matter involving the public’s legal surrogates—law enforcement and the judiciary. Such behavior is very much a matter of public concern, as is art or its absence in our society. Beatty would do well to educate himself on such rudimentary matters as the individual’s communal responsibilities in a social democracy.)

In his growing desperation to prove malfeasance, he discloses that we have run covers by Neal Adams and Jack Kirby. Is anyone shocked? Not only is this considered a disgrace of the past, but proof of future potential treachery. I suppose we could call this ontological turpitude. As the Beatty fiction has it, running covers by Neal Adams and Jack Kirby in the past is proof that I will “tear down the underground, newspaper, and foreign cartoonists that are your darlings of the moment.” We “sure wouldn’t put [Adams and Kirby] on the cover of the Journal now,” Beatty smugly states. In fact, we would—and will. An issue devoted to Jack Kirby is forthcoming, with a Kirby cover. Sorry to disappoint Beatty by putting one of comics’ greatest artists on its cover for a third time.

Beatty’s primary charge is that the Journal was “built on such ‘processed junk’ as Wild Dog” (thereby identifying himself with Neal Adams and Jack Kirby, if you can believe that).

First, the Journal is a critical trade magazine and doesn’t create comics—which Beatty triumphantly reminds us of later in his letter—but evaluates those that are produced (obviously a disgraceful activity). Therefore, the Journal covered proportionately fewer alternatives in periods when proportionately fewer alternatives were created and published, i.e. in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

Second, the Journal did not ignore nor downplay alternatives—not by a long shot. Beatty conveniently fails to mention that Carl Barks and Popeye were cover-featured immediately before and after we cover-featured Neal Adams. The five covers prior to our Teen Titans cover featured an essay by Carter Scholz on art as commodity (Journal #80), William Gaines (#81), Dave Sim (#s 82 and 83), and Michael T. Gilbert (#84) —not what you’d call indicative of a shrewd, hypocritical marketing policy designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator.

Third, there were very good reasons for putting Adams and Kirby on our covers at that time: both men had just done their first work for independent publishers after working almost exclusively for Marvel and DC for many years. All in all, not quite the contemptible sell-out Beatty would have you believe.

Nice of Beatty to identify himself with Hitchcock, Jim Thompson, Woolrich, and Fuller, though, since it was my observation he misinterpreted, I can assure him I never meant to equate their talent with his. Beatty claims that these directors and writers “were unable to create works worthy of [my] stamp of approval.” Not quite. I was actually criticizing the ghettoized mentality that considers a Fuller better than a Bergman or a Jim Thompson better than a Tolstoy — that arrogant philistinism, of which Beatty’s letter is redolent, that worships pulp at the expense of more deeply penetrating works of art. Which is not to say that Hitchcock or Woolrich are among “those-who-are-unworthy,” but that they ought not to be elevated above their betters. Certainly they shouldn’t be equated with Terry Beatty.

Beatty’s hysterical argument that the comics profession could “roll right along just fine” without The Comics Journal is beside the point. The comics profession could also “roll right along just fine” without any ethical ballast—which, come to think of it, it does. If rolling right along is your only concern—a typically impoverished premise, incidentally—then we would have to admit that our social order could roll right along without a shred of art that’s worth a damn, that the U.S. government could roll right along without a free press, and that politicians could roll right along without political cartoonists. In fact, a good argument could be made that society could roll right along much more smoothly without any of the critical impediments listed above, as long as you only want the trains to run on time. Since opinion as to the value of the Journal’s contrariness is mixed among cartoonists, it by no means follows that the Journal is a barnacle on the whale of creativity because it has inconvenienced Beatty’s egoistic prejudices. Beatty’s is the old love-it-or-leave-it attitude, made famous by the Nixon administration’s posture toward dissent during Vietnam, always adopted by members in good standing of the status quo. It always means: criticism and dissent is fine — as long as you don’t dissent from my point of view or criticize me! By logical extension, if Ralph Steadman couldn’t successfully run for Prime Minister, he forfeits his right to criticize his government; I’m sure Mrs. Thatcher regards him as a barnacle on the belly of a whale, and for good reason. No decent critic of politics or art would have it any other way.

Beatty’s sectarian implication that if you neither write and draw nor bend your knee to the appropriate creative figures (i.e., Beatty and his friends), you are a lesser human being than an artist such as himself is demeaning to the great many people who support good art and help its realization but who aren’t themselves artists. This includes everyone from conscientious publishers to museum directors to bookstore owners—people who may not create art but who have dedicated their lives to its dissemination and preservation. These are people who contribute far more to the health of good art than a mediocrity like Beatty.

Beatty’s presumed superiority is apparently based upon the premise that critics don’t create anything, a sub-category of the old critic-as-parasite argument. This is a cheesey intellectual parlor game for idiots. In fact, there is no way of creating a hierarchy among life, art, and criticism because, by any meaningful civilizational criteria, none of these concepts mean anything exclusive of the other. Life itself would be meaningless bereft of beauty or art (eating, shitting, consuming, and procreating simply not being enough in and of themselves, even in the most egalitarian consumer society); art means nothing without the critical faculties with which it can be understood and appreciated. Matthew Arnold once said that poetry was the criticism of life, by which he either inadvertently elevated criticism, devalued poetry, or—my interpretation—implied that poetry and criticism coexist as essential prerequisites to a meaningful life.

Beatty plays to the mob by frowning on displays of contempt (while displaying contempt, of course), but anyone who adopts a public position based upon principle is eventually going to find himself contemptuous of positions he finds morally loathsome. Far from being indecent, it is absolutely imperative.

I am being accused of a conflict of interest by someone who denies that being defended exclusively by his mate represents an obvious conflict of interest. Right.

But a conflict of interest is not in and of itself “morally bankrupt”; a conflict of interest is morally compromising to the extent that it becomes part of the means that corrupts the ends, but corrupted ends should be proven and not merely assumed via innuendo. Beatty fails to recognize his own conflicts of interest: a poor review of Wild Dog could damage sales, reputation, or ego, which means that he is predisposed to prefer a positive review, arguments as to objective artistic merit notwithstanding; since the Journal competes with Beatty’s Ms. Tree and Wild Dog in a finite market, Beatty’s criticism of the Journal is “morally bankrupt” because of his conflict of interest, etc. Unfortunately, there’s very little purity in this world.

Curious, too, that when we print a negative review of one of our own books, Beatty considers that such a review “is still publicity,” but that it isn’t “still publicity” when we print a negative review of his book. Do I detect a bias in his reasoning?

Beatty claims that we “relentlessly” plug our own publications; I defy him to prove this assertion. And, by the way, does Marvel Age print negative reviews of Marvel comics—even token ones? Or, for that matter, positive reviews of competitors’ books? If the Journal is “no more a serious Journal on the art of comics than is Marvel Age,” it will only be because we keep printing these sanctimonious, self-serving, letters from Terry Beatty, which I grant you, are no more serious disquisitions on the art of comics than the shameless self-hype that appears in Marvel Age.

Centrifugal Bumblepuppy was an experimental comics anthology magazine that we were proud to publish, though, apparently, none of the cartoonists who appeared in it measure up to Beatty’s definition of Roald Dahl’s “music makers”—otherwise, he couldn’t have displayed such contempt for them. The cartoonists so dismissed include J. R. Williams, Joe Sacco, Steve Lafler, Norman Dog, Michael Dougan, Jerzy Szostek, Paul OUswang, Jim Siergey, Dennis Worden, Wayne Honath, Krystine Krittyre, Craig Maynard, and others. Sneering at the work of so many talented cartoonists isn’t terribly politic coming from someone who tries to pass himself off as speaking on behalf of all creative persons everywhere.

As for the Journal’s “scorched earth policy,” we could hardly compete with the level of sheer nastiness and bunker mentality found in Beatty’s own comic, Ms. Tree, the letters column of which vent Beatty’s (and Max Collins’) opinions in an orgy of smarmy self-aggrandizement and rampant bullying. The letters column is usually filled with fulsome praise (inevitably followed by responses that begin with something like, “Thanks for your thoughtful comments about Ms. Tree..!”), but any stray reader who gets a bit uppity is bullied into submission. In issue 38, for example, one reader politely objected to the stereotyped characters in the book, and was called a “pompous knucklehead” and summarily dismissed as one of those “comics fans who effect an attitude of being superior to the mere artists and writers who only create the damn stuff.” Although Collins usually writes the replies to letters, the general tone of which we may assume Beatty approves of, Beatty manages to get in a few lumps himself. Beatty wrote a column ad dressed to the book’s readers that began, “We have been hearing a certain amount of whining from some of our readers concerning our new format”—such whining being intolerable to the genuses who produce this silly book—and concluded by telling the winners, via a quotation from Don Westlake, to “ ‘Shut up, or I’ll throw you down the stairs.’ ” Between these two testaments to tolerance and liberality, Beatty trots out his monthly income (a niggardly $500 per month), lectures his readers as to his own virtuousness in drawing Ms. Tree in the first place, and complains that he “cannot pay my rent, make my car payments, buy groceries, art supplies...” on his Ms. Tree income. It sure is tough in that garrett.

Apparently, Beatty truly believes that he has answered one of humanity’s highest callings, and that those who do not genuflect before his talent will be thrown down the nearest staircase—metaphorically if not literally. When it comes to scorched-earth policies, we have nothing over Beatty.

Beatty is absolutely correct about one thing, though, and that’s the duration of his phone call to me. It was three minutes, not 10; my apologies for the inaccuracy. All I can say is that three minutes of incoherent ranting from Beatty sure felt like 10 to me.

All in all, I think Beatty’s letter is a perfect example of what I call radical subjectivity. It’s one thing to disagree virulently with a critic (or the publisher who publishes the critic), quite another to read into such criticism a conspiracy of monolithic proportions and conclude that specific criticism of his work reveals a contempt for all art and all artists everywhere.

Ever since Marvel and DC were forced to grant economic concessions because of pressure from the independents, the new generation of creators who work on corporate properties have been whining, complaining, grousing, bitching, and generally proclaiming their rights to anyone who would listen. Self-interest, narrowly defined in almost purely financial terms, has become the prevailing ethic among the super-hero creators, and egos have naturally kept pace with an accelerating greed, exemplified by the feet that such creators will continue working for the corporations that have systematically enslaved, exploited, and ripped off their brothers as long as they get theirs. And, with the advent of an obsequious trade press and a critically prostrate but loudmouthed public, artists’ egos have become nearly as ugly a spectacle as publishers’ avarice. The comics profession would benefit if creators generated a sense of obligation rather than privilege among their ranks. Instead, creators who are no better than mediocrities are encouraged to allow their egos to run amok. Artists like Beatty, no matter how sincere or how highly they think of themselves, are as much a part of the problem as pandering publishers and an easily bamboozled public.