Arthur Ranson, to me, is one of the finest comic artists to come out of the United Kingdom. With a style that appeared almost fully-formed from his 1972 debut in the oft-overlooked ITV television comic Look-in, he occasionally brushed up against what he perceived as an all-encompassing aesthetic tradition of British comics which stifled creativity, yet remained resolutely himself. Over the 35 years of his career, he worked on various properties for Look-in and, later, Marvel and DC, though he is surely best known as artist, from 1989, on some of 2000 AD's most celebrated features, including "Judge Dredd" and "Button Man" with writer John Wagner, and "Anderson: Psi Division" and "Mazeworld" with frequent collaborator Alan Grant.

Even though he hasn't worked in comics since his retirement in 2007, Ranson cannot be said to be out of touch: at 84 years old, he still actively creates art—having gone from traditional to digital tools—and operates a blog on which he shares his thoughts and updates on current happenings. I had the distinct pleasure of speaking with Ranson at length over email correspondence in June and July of 2023. I am deeply thankful to Ranson for speaking with me about his extensive career and his thoughts on style, about art as practical application versus art as its own end, and about comics as art and business. This conversation has been edited for flow and legibility.

-Hagai Palevsky

* * *

In the brief biography page on your site, you mention that your decision to become an artist was a result of your teacher's encouragement when you were four years old. Was there any artistic background in your family? What was your first experience engaging with art?

The teacher, Miss Skillycorn, has a lot to answer for. There were no working artists in my, or my extended family's, background. My brothers and I read comics and I recall being impressed by the illustrations in some pre-war storybooks that came into the house. I can only imagine the books were a gift from someone; given that the first five years of my life were during wartime it still seems surprising that my parents and others were willing to spend money buying their children comics. My older brothers had them prior to my arrival. It was looking at them that made learning to read when I got to infant school seem easy.

Was it that early on that you'd wanted to become a comics artist, specifically, or did that particular ambition come later?

At that stage and for some time after the wish was to be an "artist." There was no clear or practical idea of how that might manifest itself.

At what point did you start thinking about the actual human side of comics production? Was there a moment when you became aware of the fact that there were people making these books for a living?

That's really interesting. I've read "Dan Dare" so I'm familiar with Hampson—I suspect this side of British comics history almost always comes back to two big names, Hampson and Don Lawrence—but I'd never heard of Worsley until just now. I've just looked up his work, and it's beautiful in that very "British classical comics" way. How were comics perceived—as an artform, as a work prospect—in your youth? Was that something that ever came up at all, after you'd resolved to become an artist? I remember you went to art school, but I'd imagine that there wasn't much focus on comics, if at all, in the curricular sense.

In my youth, comics were generally not regarded as an artform or seen as a work prospect by anyone I was aware of. When moving up from junior school, comics were left behind. They ceased to be part of the cultural landscape for me, and, I suspect, for most others. At art school, even after Pop Art became a thing, comics were not mentioned [and did not] receive any attention.

I'd love to hear about your first couple of years working as a stamp and banknote designer - that's certainly not the sort of job that you see discussed very often. How did you get into that field?

This is a condensed black and white version of events: aged 16 and wishing to go to art school, the adults in my life decided that the offer of a five-year apprenticeship was the better option. One of the art school tutors had connections and arranged an interview with Waterlow and Sons, a security printing company. I was offered the position of an Apprentice Stamp and Banknote Designer. I did not want to do it but the only alternative I could come up with was joining the merchant navy. The designers' studio consisted of five men and me - the youngest by 20 years. Judging from the ages of the other guys a new apprentice was taken on at 20-year intervals. I hated the job and its restrictions. The first year was the most unhappy period of my life. My time there was spent learning to work on Bristol board in watercolors, making stamp size portraits and landscapes. This training did come in useful when I was later working as an illustrator. In the second year, the firm sent me to art school one day a week. In the third year, I convinced them that two days a week would be better. Those breaks were the bright spots. The day the apprenticeship ended I left the job.

What made it so miserable?

It was miserable because I was 16, no doubt with usual adolescent hang-ups, spending three hours a day traveling to and from work where there were no others of my age or interests. I was at a place where any wish for creativity was discouraged in favor of discipline and following precedent.

What's interesting to me about that sort of work is its distinct separation from what we consider "art"; stamps and banknotes certainly feature illustrations and design, but we view them as objects of pure technical function, as opposed to the more indulgent nature of "pure art." What was your approach to that divide at the time?

I was too young to have formed any coherent intellectual ideas about fine art as opposed to commercial or applied art. Had I been able to articulate my dream, it would have been to be a painter of fine art abstract works.

It's interesting that you should mention abstract art, specifically, since the art you later became known for was decidedly and overtly naturalistic. Were you drawn to the abstract at the time?

Yes, I was. The American Abstract Expressionists were just beginning to make an impression on the British art scene. There was a very good History of Art tutor at college who introduced Kandinsky, Mondrian, Paul Klee et al., and described the theory that painting was a progression from naturalism to abstraction that I took to heart. Most other tutors were at the Walter Sickert stage, which was a little less inspiring.

Can you tell me about the years between that apprenticeship and your entry into comics? From what I understand you remained in applied art for about a decade.

A few months working as a shop assistant and a builder's laborer. Three years at art school. Teacher at a Dagenham secondary school. Fond memories - the kids were great. Laborer in tea packing factory. Lettering Artist at Thames Board Mills. Color Mixer at Letraset. Studio assistant in a design studio.

These jobs required some display of interest in art in order to get hired, but none made much if any use of it, so pretty boring. Freelance artist/illustrator, mostly advertising. The work I did was based on my experience at reproducing photographic images as paintings. Fortunately it was quite the fashionable thing with both advertising agencies and magazine publishers for a while. It was okay. I was quite happy to do it, but for the most part it did not require much imagination or creativity.

And I understand that was when you got into work with Look-in, which I assume was more fulfilling as far as creativity is concerned. How did that opportunity come about?

I visited Look-in as a potential customer for celebrity portraits. I did a few. One day while delivering a job, there was staff concern about Brian Lewis dropping his work on "Les Dawson is Superflop" [a strip vehicle for the English comic performer]. I told them I could do it. Not strictly true, but a week later after many failed attempts I was able to produce a page acceptable enough to get me the job.

When you mention Les Dawson it makes me think about how, as a cultural phenomenon, Look-in is something of an extinct species; it employed comics, as an artform, in a way that sought to appeal to the general populace to a degree that comics nowadays appear largely disinterested in. Comics based on TV series certainly exist now, but only in a niche that appears to perpetuate its own insulation, and you don't see many comics that capitalize on pop-celebrity culture with that as-it-happens immediacy. How did you feel at the time, working on those comics? Were you personally interested in the properties and artists you were making comics about, or was it strictly work?

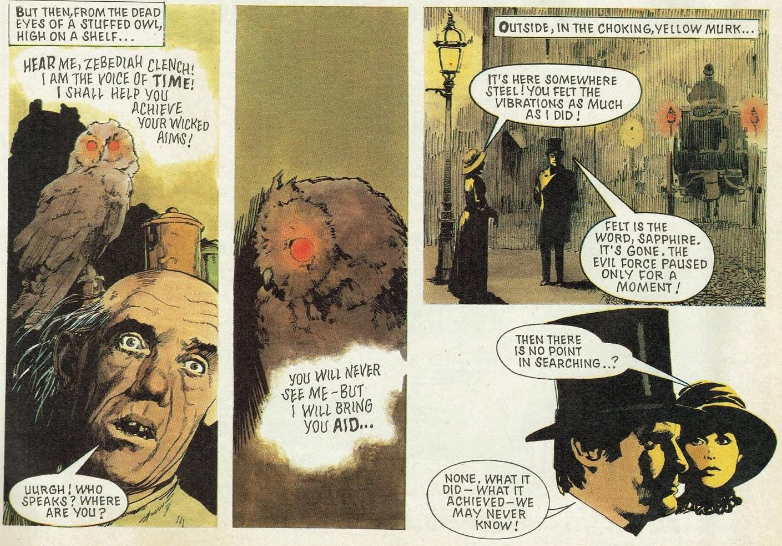

I don't believe I had a television at the time, so in that sense I had no interest in the properties chosen. Initially just work, a way to earn a living, the significance of working at Look-in for me was that over time I became more and more interested and enthusiastic about comics - how they worked, what they might do, how to best visualize stories. Initially drawing only 'funnies' I became keen on doing more dramatic 'realistic' strips. Having experimented with different styles, been influenced by various and disparate comic book artists—editor Colin Shelbourn was very tolerant of me—I wanted to develop my own drawing technique and way of conveying narrative.

Nowadays we are used to seeing a wide variety of personal artistic styles with lots of creative thinking going on. At that time, with the exception of John Burns, what comic art was supposed to look like was typified by football comics and war comics. There were people doing this stuff who were very good at what they did, but it seemed to me limited by tradition and by what material was available to make comparisons with. Hampson and Bellamy were figures from the past. Brian Bolland et al. in the future.

What was the work process like at the time? I'd imagine there was a lot of editorial oversight and brand maintenance, between the celebrity strips and the ones based on television series.

The work process was straightforward enough. Got the script. Did the work and took it in. No doubt the editorial staff dealt with license-holders and ensured that the strips were OK with them and, if they ever read them, met the featured celebrities' approval. The only feedback I ever heard was positive, from Michael Bentine for "Potty Time" and from [animation creators] Cosgrove and Hall for Angus Allan's "Danger Mouse" scripts. I assume they thought my artwork was adequate. Though I was never told until too late Joanna Lumley did contact the office and offer to sit for more "Sapphire & Steel" reference photos.

I remember thinking of your style as fairly fully-formed, until I saw a "Danger Mouse" page of yours at the Cartoon Museum in London and was rather surprised that it was the same Arthur Ranson; I only later found out that you also did "Inspector Gadget" and "Count Duckula" comics. How did you adapt to such radically different projects, whose predefined styles and looks were so far from your own?

Following predesigned styles seemed simple enough. All the thinking had already been done. I was happy enough to do them and had some fun with "Danger Mouse". I did ask and got "Danger Mouse" to be nine frames instead of the six it originally was, so as to be able to make a more engaging page, a change that was extended to other similar style strips. In this format, a two-inch picture of a character's head was no more interesting than a one-inch picture. Presumably paid the same for either, writer Angus Allan was not amused by the change. "Danger Mouse" was the most popular of these strips with readers - enough for its run in Look-in to be extended beyond, I think, its appearance on telly. Cosgrove and Hall liked it so much as to get Angus to write scripts for them, so he may have forgiven me for the extra work I caused him. They gave us each a nine-inch plaster model of Danger Mouse and Penfold.

If you don't mind sharing, what were the working conditions like during your time there? I know that other British publishers of the same era—DC Thomson, in particular—were often criticized for their pay.

Don't recall what the page rate was when I first started—modest but reasonable—but it increased over the years. Look-in was by far the best payer in the business. All artists got the same page rate. By the time I left it was £200 per page, if I remember rightly. It was some years before 2000 AD matched what I had been getting, and that only after asking for a raise.

So by going from Look-in to 2000 AD you initially took what amounted to a pay cut? Or did they match that rate in order for you to start working for them?

Yes, it was a pay cut, but, warned that Look-in was on the verge of folding [Look-in ceased publication in 1994], there was little alternative. Pay rates from other publishers I approached—Thomson and someone else who was planning a TV-related comic—were even worse. All part of the joys of being freelance.

Yes, as a newly-inducted full-time freelancer I'm certainly familiar with that feeling.

Good luck freelancing. Bit nervy at first. I found the freedom it offers makes it worth it.

[Laughs] Thank you. It's certainly an interesting change of pace, the freelance life. Did you have any particular sentiments or impressions toward 2000 AD prior to joining?

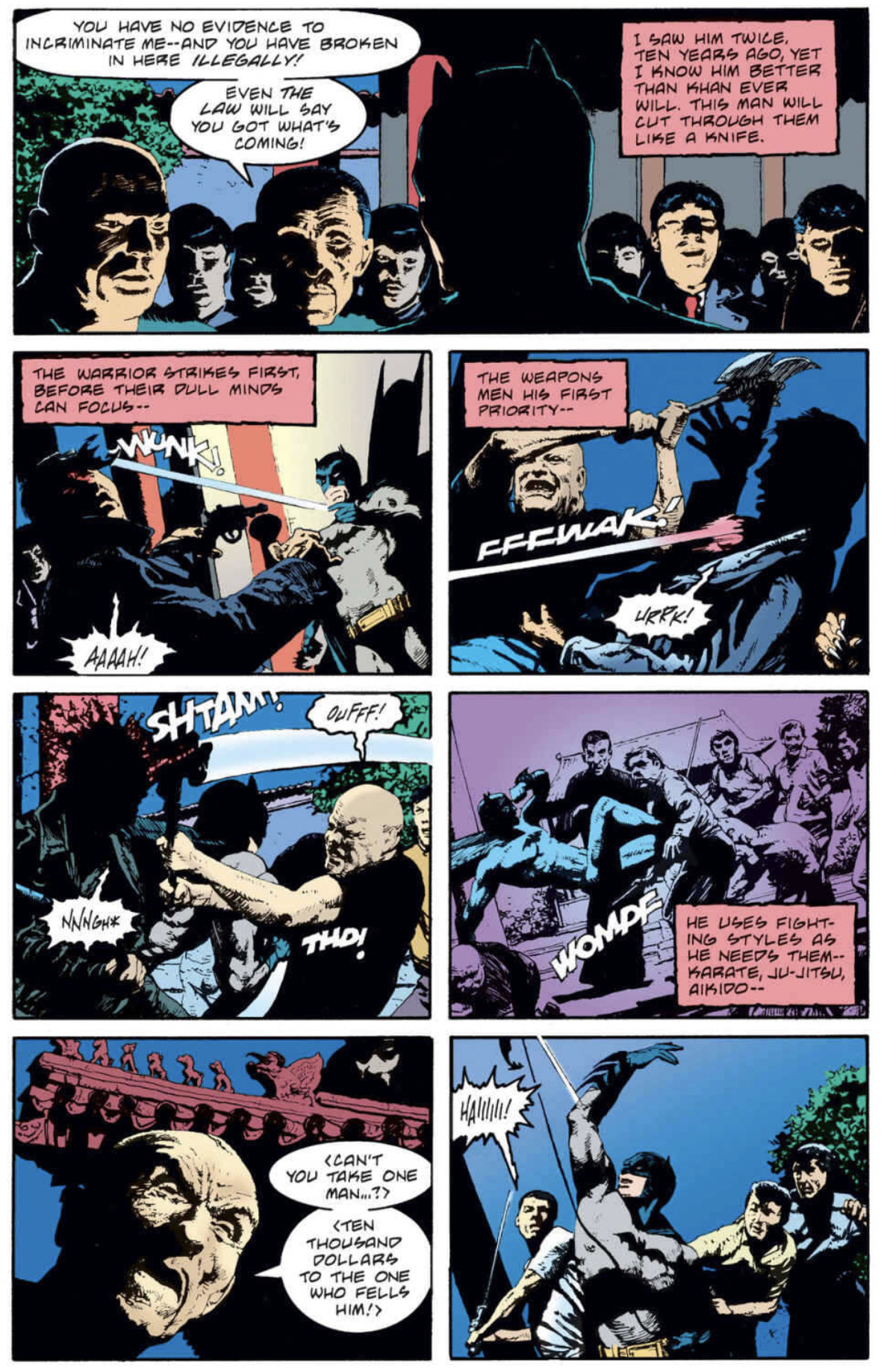

I was not confident that they would take me on. Though not a regular reader of it, I was aware of 2000 AD as a place where new arrivals to drawing comics were welcomed and getting the breaks, so I imagined I might be considered too traditional for their taste. Although 2000 AD only really took off after the arrival of Brian Bolland, it was still considered the happening place - certainly by the artists working there. In the event, at my interview with then-editor Richard Burton, he was very kind and complimentary, offering me a "Judge Dredd" script on the spot - "The Dungeon Master" by John Wagner [published in Judge Dredd Annual 1990]. About my drawing of that, the thing I still feel a little foolish about was my inclusion of wires and leads to bits of imagined technology because I hadn't caught up with what might be possible in the future.

This brings me back to a thing you said earlier, about Look-in being rather constrained by British comics tradition. When you joined 2000 AD after your years at Look-in, stylistically, there was something of a contrast between the Progs' heady, jagged ethos, represented by people like McMahon or O'Neill, and your own tendency toward naturalism. Did you feel "different" in that way?

I guess I was different, but never thought to try changing. Nobody at 2000 AD was doing anything I had any wish to emulate. I was more interested in continental artists - not for how to draw, I had my style and was stuck with it for good or ill, but for page layout and narrative technique.

Was the magazine a better vessel for the sort of creative freedom you were looking for?

After the fairly tame Christmas Dredd story I did ["The Santa Affair", published in 2000 AD Winter Special 1989] next came a Psi Judge Anderson story that allowed me to continue with some ideas I had begun to try out on the "Sapphire & Steel" strip for Look-in. These were further expanded in the next Anderson strip, "Shamballa", where I took further liberties with page layout and panel shapes. Comics seemed too often to be like slideshows, jumping from one scene to the next. I wanted to try for something with more flow and continuity. It was to that end I was introducing more panels than were scripted. It is to 2000 AD's credit that I felt free to exercise any creativity I might have. Nobody was commenting on what I did, let alone complimenting. I assumed they were content since they continued to send me scripts.

You mentioned your interest in continental artists and the way they differed from storytelling conventions in British comics; if I understand correctly, this would have been the same time that the Anglophone sphere was becoming increasingly aware of the Métal hurlant school of creators. Were there any creators in particular that made you feel the need for an expansion of the British storytelling vocabulary, so to speak?

I was buying Continental comics while on trips there. That meant seeing a wide variety of styles and approaches and being struck by the variety of comics and the respect they were given compared to the UK. The two creators who emerged for me were Moebius and Philippe Druillet. Each were to influence me in different ways.

What did you take away from Moebius and Druillet?

From Moebius that you could do more with less. From Druillet that there were no boundaries. Or at least what there were, were self-imposed. [Mine was] too English a sensibility to match his exuberance, but his work was an encouragement to try.

Did you have the same interest, or find the same inspiration, in other geographical spheres? Be it the first “boom” in translated manga which came a bit later, or perhaps the concurrent wave of Latin American work?

Was interested on manga and its differing approach to drawing, narrative, 'sound effects' and panelling, and I had a copy of Akira and a few Japanese comics, but I don't know that it had any direct influence on what I was doing. Could never understand the preoccupation with those big doll's eyes the artists were so fond of. Apologies to Latin America, but their comic output seems to have passed me by.

You also spoke about your work on Judge Dredd and Psi Judge Anderson, which I find interesting, because even though you didn't do a lot of the main Dredd serial you are probably the artist most heavily associated with Anderson, which is quite possibly the most popular of the spin-offs. Did you find the spin-off easier to work on than the core title?

Not sure 'easier' is the word, but through Alan Grant's scripts, Anderson was a more interesting and nuanced character than Dredd and more in line with my interests, so more of a pleasure to draw. Alan's Anderson universe was broader and less restricted than Dredd's, which offered a wider canvas and more opportunities to play than did Dredd's. Play in the sense of 'make stuff up' with the challenge of getting whatever flight of fantasy to be convincing. The few Dredd scripts I got from John Wagner were very minor-key space fillers. The Dredd story I would have liked to tackle—Dredd in the Badlands, or whatever they are called—was only ever in my head.

Did you ever ask 2000 AD to write your own material? Was that something you were interested in at all?

Just the once. I can't recall the detail but a female vampire mutant from the Badlands gets into the city. She was the hero rather than villain of whatever events I had her involved in. Dave Bishop was editor and said no thanks.

I would've liked to read that. I assume by the Badlands you mean the Cursed Earth?

Cursed Earth, of course.

Speaking of Wagner, let's talk about "Button Man", which was, and still is, one of the handful of Toxic! titles to remain in publication after the magazine's shuttering. What was your experience, working on it for Toxic! the first time around?

John, Alan, and some other 2000 AD notables were doing Toxic! as a creator-owned publication. Simon Bisley was involved doing some "funny" dog strip. I was only ever on the outside as hired help and had no attachment to the thing. Couldn't say why I had the idea that all was not well, but it was no big surprise to me that it folded. Asked me to do a story ["The Vampires New Year"]. Must have been near the end of Toxic!'s life, as after one episode it was cut short, one further page was drawn and that was re-scripted with the dialogue taking it from intended horror to some kind of jokey finish.

How did the move from Toxic! to 2000 AD come about? Did they require you or Wagner to make any changes? As far as tone and aesthetic go, it's certainly a more "realistic" work than much of the magazine's fare, both then and now.

I believe "Button Man" was intended for Toxic!, but when it folded John took the idea to [2000 AD]. John had enough clout for them to take it on despite it not being science fiction or fantasy. That "thirty minutes into the future" tag it was given was intended to cover the discrepancy. It was only then I started work on it. It was never in Toxic!

On a personal note, "Button Man" is among my favorite things that both you and Wagner have done, so I'm fascinated by that change; to me that transition between the first and second chapter feels so seamless that I'm surprised that that wasn't the initial plan.

Unusually, John and I retained copyright—whose idea was that?—at the cost of a reduced page rate. John's first "Button Man" story had Harry dead at the end of it. I liked the thing well enough to, without consulting John, change that ending to make a sequel at least a possibility. Initially I would talk to John about any changes to his script I would like to make, but he got fed up with being pestered and gave me the freedom to do as I thought best. Mostly that would entail adding extra frames.

That element of rights ownership is a particularly interesting contrast to much of the preexisting "system." It's hard to discuss Toxic! without the necessary context of that whole wave of new comics magazines that sought to disrupt the status quo of British comics of the time: Deadline, Crisis, the A1 anthologies - titles that sought to change British comics both as an aesthetic and as a business. As someone who by that point had been in comics for the better part of two decades, and who was very conscious of the limitations of the Brit-comics tradition, how did you regard those efforts?

I had sought and obtained copyright before, for "The Beatles Story" from Look-in. I was aware of A1 as an attempt to do something new. Deadline and Crisis have left no impression. You give me too much credit for having an overall knowledge of UK comics. I did once begin to research and write a history of comics, but that was long ago and most of what I learned has since faded from lack of use. For a while I was writing "Ranson Notes", a monthly opinion piece for Comics International, but as a jobbing artist I became more insular and less concerned with being critic or historian.

[Laughs] Fair enough. I hadn't realized that you retained the copyright for "The Beatles Story"; I'd assumed that the rights for most of the material in Look-in were in some manner of limbo, since we rarely see any reprints of them. The only reprint I remember recently is last year's collection of "Robin of Sherwood", from Rebellion, which you also drew.

The legalities of Look-in strips were confusing since so many people had some claim - the writers and the producers of the shows, the performers, Look-in, its writers and artists, ITV publishing. Don't know how "Robin of Sherwood" evaded the problem. Something odd there, since the publishers of the collection never paid any reprint money to the creators.

I suppose in a way your Ranson Notes column was the antecedent to the blog you run nowadays, which also serves as a vessel for things you personally find noteworthy. "Mazeworld" was also conceived for Toxic!, wasn't it? Though it wasn't published for a few years after that. As I understand, you were very involved in terms of collaboration on that.

"Mazeworld" came long after Toxic! had been and gone. I never added anything to the eventual script, but it was after Alan made a mention of some idea he was having that led me to do a drawing of the world as I imagined it, and seeing that led him to go fully ahead creating the story. It ran in 2000 AD to not much acclaim. There was a small fanbase who asked for it to be collected, which Rebellion eventually took note of. It was only after its reprint as a collection that it achieved whatever standing it now has.

I realize that much of your work with Alan Grant had a preoccupation with the mystical and fantastical, which is a rather sharp contrast to a lot of your other, more grounded work, such as "Button Man". Did that require any shift in approach, or did it all come with the same ease? I've noticed that that fantastical aesthetic—especially the more demonic elements—is also present in your recent digital artwork.

Never thought of one being more difficult than the other. Different but not harder. "Button Man" involved research for the appearance of real-life objects and locations, whereas Anderson required imagination and invention. Making things up was, on balance, a preference. That's fun to do - hence the demon 'paintings' on the website. Each script presents its own problems. In addition to turning words into convincing visuals, I always felt strongly about maintaining the narrative, making the temporal run of events clear and flowing. My habit of adding extra frames was to that end.

The fantastical element was a shared interest with Alan in which I imagine we encouraged each other, if not for DC putting a stop to it. I believe it was Alan's intention to introduce it into the Phantom Stranger/Batman story [i.e., the Batman + Phantom Stranger one-shot from 1997]; as it was, Phantom Stranger became little more than a spectator. Which was a shame. I had a collection of Phantom Stranger comics and was a bit of a fan of the character. There was stuff about death in it which was intriguing.

Was your DC work with Grant the first time that you'd worked on a property that you felt more attached to or interested in as a reader? Did that color your approach at all, or do you not share that sort of sentimentality?

I felt no particular attachment to either of those two characters. Neither had been part of my early comic reading. Phantom Stranger was unknown to me until after starting work in comics. Being asked to do Batman was some sort of compliment, but I was never a fan. As a youth, the comic I was reading was the Eagle. Captain Marvel—the original C.C. Beck version and Captain Marvel Jr. by Mac Raboy I had met as a kid—were the only superheroes I had a liking for. DC and Marvel were not part of my experience until after I began to draw comics. Then I found some early Batman stories with their giant domestic appliances pretty dreadful.

Were you in touch with Grant at all after your collaborations had ended, until he passed last year?

He and I were on Christmas card exchanging terms. I knew he had health problems but wasn't aware of the exact nature or seriousness of them. That he was the only person in comics I regarded as a friend was due to his warm and amiable personality, rather than mine which is less so; I can still miss him.

I never got a chance to meet him, but he really did seem to be a person liked by everyone who'd interacted with him, at least in the comics sphere. Your website mentions that you did a brief stint working in guided imagery and psychosynthesis counselling. How did you get into that world? Obviously it's very different from the rest of your work up to that point.

I'd long had an interest in psychology, and had read Freud, Jung, Adler, Perls and Assagioli, the founding father of Psychosynthesis. Whatever the impulse, I decided to enroll at the Psychosynthesis and Education Trust as a student. Part time, three days a week. It seemed doable while still able to earn enough from comics to get by. The course required I saw a therapist, so that was all very mind-expanding. Though I got to practice as a counsellor for only a brief time [2001-02], the whole experience was well worth it.

The psychosynthesis work strikes me as particularly interesting as it was, if I understand correctly, the first time in at least 25 years that you worked in a field outside of art. Is that correct?

That is correct.

Did either "part" of you—the counseling and the art—interact in your mind at all, or did you view them as two completely separate endeavors?

I never regarded the two interests as distinct - each informed the other, each discipline and interest influencing how I worked in its counterpoint. To some good effect in the comic book work, it would seem, since the stories produced have had such longevity. With all due modesty and recognizing their significance in the success, I am not aware of any other Grant or Wagner strip still being reprinted and bought so many years after their creation. It is flattering and unexpected, but I can only suppose I must have been doing something right.

You started working for 2000 AD at the tail end of the '80s and worked pretty consistently until 2007, so you were around to witness much of the magazine's most tumultuous era, as it struggled to find new directions and sales during the '90s. How did you experience that, as a freelancer working for the magazine? Did it concern you, at the time?

I was too wrapped up in my own affairs to have been concerned or even aware of any tumultuousness. As you say, I was working consistently, so whatever the problems I was not affected.

At what point did you decide you were officially retired from comics? Was there any particular point that made it a concrete, definitive decision?

There had been a number of life-threatening health scares. Being brought face to face with one's mortality tends to give one pause for thought. There were breaks from work while I was hospitalized. Back home, after submitting a couple of unsolicited 2000 AD covers with the assumption that I would get back to business, what I thought was 'Do I really want to spend whatever time I have left drawing comics for folk?' and the answer was, no, I do not. All very existential. There was no plan as to what I might do instead, but I could get by on pension money, so I thought to figure that out later.

I'm certainly glad that you got through those health issues, and I hope you're doing well nowadays; I can only imagine that sort of perspective shift. I don't know how much you see of it, given you're not on social media (though from your blog I can see that you do keep up with comics news), but there's been a lot of talk in the past couple of months about publishers' treatment of comics creators - especially as pertains to irrational demands compared to compensation, which is obviously nothing new. How would you describe your overall experiences with the publishers you've worked with? Were there any particular issues that you viewed as endemic or systemic?

I have seen that story. It would seem to be an American problem. Nothing like that ever happened to me or any UK comic creators I am aware of. Rebellion still takes care of me, arranging deals I would be unable to do on my own, so no complaints at all about my dealings with UK publishers. Or US ones, come to that.

How much have you kept abreast of comics since you stopped making them? Do you still read them at all?

Kindly enough, Rebellion send me 2000 AD each week. It is not possible to buy comics in the town in which I live, but the local library has one small shelf. Mostly DC and Marvel; a little manga and the odd independent. So it is mostly digital. There is a Google Alert thing I use which gives me all the latest comic news from the Internet. I get regular mail from the website Bleeding Cool, which talks comics. Both these sources are of course mainly concerned with superheroes, with which I have only a distant relationship. Hopelessly out of date would probably be a fair description.

I know you don't do conventions or signings very often, so I'd love to hear about how you engage with the more communal aspect of comics, if that's something you're interested in. I know you did a signing last year, at Gosh! Comics, for the Best of 2000 AD books. How did that feel?

Don't think I could be accused of engaging with the communal aspect of comics. Sounds more sociable than I am. I did my share of signings in the past, when and if I was invited. Enjoyed the time at Gosh! despite being exploited by a guy with hundreds of 2000 AD I ended up signing.

[Laughs]

Had fun at one in the company of Bill Titcombe, where we each did caricatures of punters. A successful day at another, when I learned visitors were willing to pay for signatures and sketches and was able to raise £400 or £500 for charity. My feeling was that if readers wanted to meet us then attending was the least we could do, since they indirectly paid our wages.

We mentioned the digital artwork you publish on your blog. I've been very glad to see that, even though you no longer make comics, it hasn't affected the wider pursuit of art. How did that transition, from physical to digital media, come about?

I use an app called Paint. Don't recall how it came about that I have that. I'd been advised that it is the worst of all the painting/drawing/design apps available, but once I got it I found it suits me. Never got the drawing pad and pen that goes with it, but I have sufficient hand/eye coordination to use a mouse to 'paint' and do line work.

Does it feel any different, to be making this sort of art for yourself—and presenting it—on your own terms, rather than strictly for paid for-hire work?

The major difference is that there is no need to buy art materials. Self-indulgence and not owing any responsibility to others was in part the aim when leaving the profession.

I'm not so detached as to not hope there is an audience for what I put out, but [the pieces are] essentially done because it entertains me to do them and uses some part of my make-up that requires expression.

Are you a "hindsight" sort of person? Are there things, either specific projects or more overarching concerns, that you revisit in your mind and wish you could change or do over? Or is the past more of a solid certainty that does not beg revisiting?

I can see drawings in my work that might have been done otherwise, but what is done is done. Mostly I take a rather detached view of my comics career, which was pretty unlikely from the start. Whoever it was that thought to give me a Wikipedia page bought me more attention than I would have expected.

[Laughs]

How about this: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” (L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between.) In general: "Non, je ne regrette rien."

Has your view of comics, as a "capital-A" Artform, changed over the years - first as you went from reading them to making them, then later once you stopped making them?

Not sure I ever described comics as a "capital-A" Artform, but that is close to what I thought. I believed, and still do, that the format is capable of carrying more significance than is generally recognized. A good deal of what is produced is puffery and brings to mind what [comedian] Stewart Lee has in mind when he talks about "content providers." Comics are not the only art form that could be said about.

My relationship with them has changed. Now only a detached observer rather than the enthusiastic reader and buyer I once was. It was no wrench to give away the hundreds of publications in the collection I had on my bookshelves. I grew away from them for reasons that would take more psychological searching than I am prepared to do.