From the jump, Blood of the Virgin announces itself as more hot-blooded than most comics pitched to crossover to the New Yorker tote bag crowd, which come off virginal in comparison. Take another masterpiece whose serialization I diligently followed for over a decade, Kevin Huizenga’s The River at Night, and contrast its police officer starting to suggest one might consider masturbation—though “some people think it’s a sin”—as a method by which a man can make himself sleepy, to Sammy Harkham’s presentation of an active masturbation fantasy as an array of disembodied faceless women in the border above the first few panels of page one.

Maybe it’s just an L.A. thing. Huizenga identifies himself as part of a Midwestern school of cartooning rooted in the the gentility of Frank King, from which Chris Ware, Dan Clowes and Nick Drnaso all stem. Harkham lives in Los Angeles, where the sun shines brighter. The film industry situates itself in relationship to that light, and turns the city into a land of looking, where visual spectacle reigns. Los Angeles’ cartooning culture is defined by the production of animation, but there’s also Love and Rockets, an absolute heater of intermittent emotional devastation buoyed along by the pleasures of bird-dogging the big-titted. As film aesthetics define what our culture considers attractive to the eye, cinematic pacing sets a standard for comics readability. Harkham’s grids read as smooth as those of Los Bros Hernandez, but a small detail of background casting the artist pointed out elsewhere on this website seems to capture the book’s precise mixture of cartooning classicism and sordid subject matter: that’s Carl Barks and Gil Kane at the strip club.

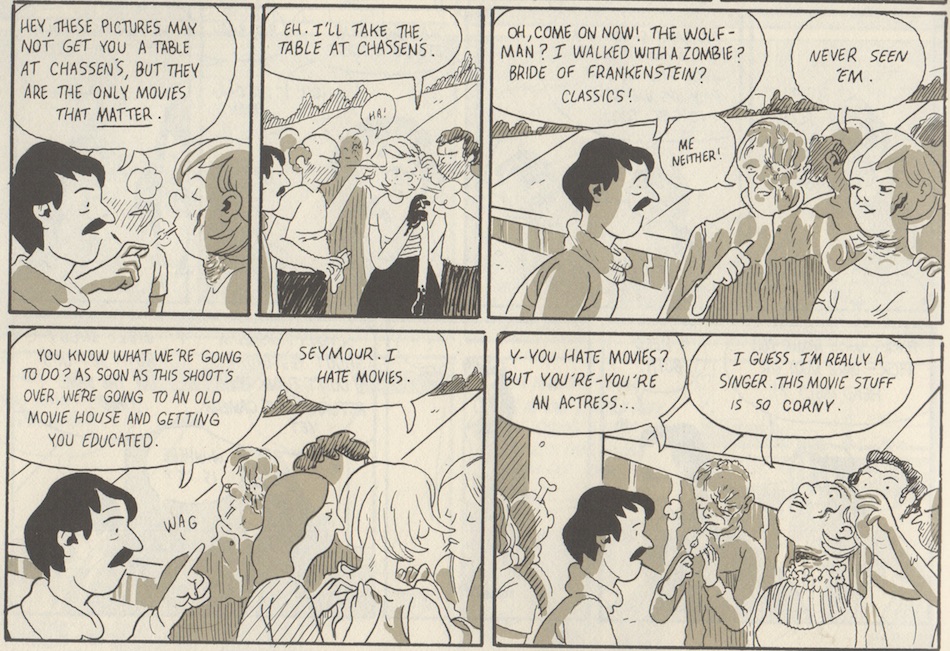

The opening masturbation fantasy is immediately interrupted; we enter into the book’s relentless pace, set by the demands people make of one another in social and professional interactions. We are introduced to Seymour, the book’s star, complaining about the lack of privacy in the house to his wife, who has recently given birth to a small child - and so we are informed of the economic reasons keeping their eyes bleary and restless. Ushered forward into social interactions and their attendant obligations, we are reminded that life in Los Angeles is what its preeminent cartooning chronicler, Matt Groening, called Life in Hell. Set in the 1970s, most of the characters in Blood of the Virgin work in the world of low-budget horror films, a milieu adjacent to the production of pornography, at least by the standards of the flattening shorthand term “exploitation” - and while the book never addresses pornography by name, the twin currents of sexual desire and power dynamics on which the industry makes its millions are just as much the subtext here as they are in any adult’s significant life experiences.

In the fraught compressed time of the book’s onrushing series of instances, sex within marriage is a negotiation between two people trying to achieve their own satisfaction. Masturbating, undertaken alone, exists as a race against time before someone else wants something from you. Seymour’s fantasy gets interrupted, but his wife gets her own masturbation scene, attempting to steal a moment away from the household’s demands. The baby cries, sound filling the house, while Ida lays on her stomach on the sofa. Her climax comes, her word balloons covering up those of her off-panel child, and then, in the next scene, she’s at the stove, wordlessly peaceful. Given the schema of the book, a big wordless panel always constitutes a relief, a gasp for air before we’re buffeted anew into the back and forth of people talking to people expecting a response.

Beyond the pleasure of a later sex scene, which gets to be wordless for the length of its occurrence, a greater respite is provided by scenes of driving. There’s a real show-stopper of a six-page scene spent roving over hills to show the landscape at night. Driving has its own connection with sexual power, as well as its own connection to the city of Los Angeles. This is the secular grace that exists within the world of the book: sometimes you’re going from one place to another, and no one is talking to you.

When violence erupts, it’s unremarked upon afterward, a borderline-hallucinatory escalation of the dynamics predicated on aggression that’s usually sublimated. Its first shocking intrusion comes early on, at a party scene it’s hard not to think of in the same terms as Eyes Wide Shut. A stripper performs affection for Seymour, and is then choked, seemingly to death, by another man. She’s never spoken of again, her death of no consequence to the larger narrative, as if it happened in a dream.

Harkham’s cartooning applies a metaphysics to the observable world: the injuries that most leave a mark upon a person are those self-inflicted. Seymour gets punched in the face and falls down a flight of stairs, but this doesn’t alter his character design so much: the bruises and bandages upon his body in the latter parts of the book all follow an accident sustained driving drunk. Ida, after masturbating, indulges in a deliberate act of self-harm, burning her hand on the steam escaping from a tea kettle at full boil. Afterwards, her hand is wrapped in gauze for other characters to inquire after, and Ida lies to them casually. “Oh, I punched a dumb cunt in the face,” she says, blowing cigarette smoke at an actress she surely suspects her husband of cheating with. Her name is Joy, and she has her own scar upon the body she doesn’t want to talk about.

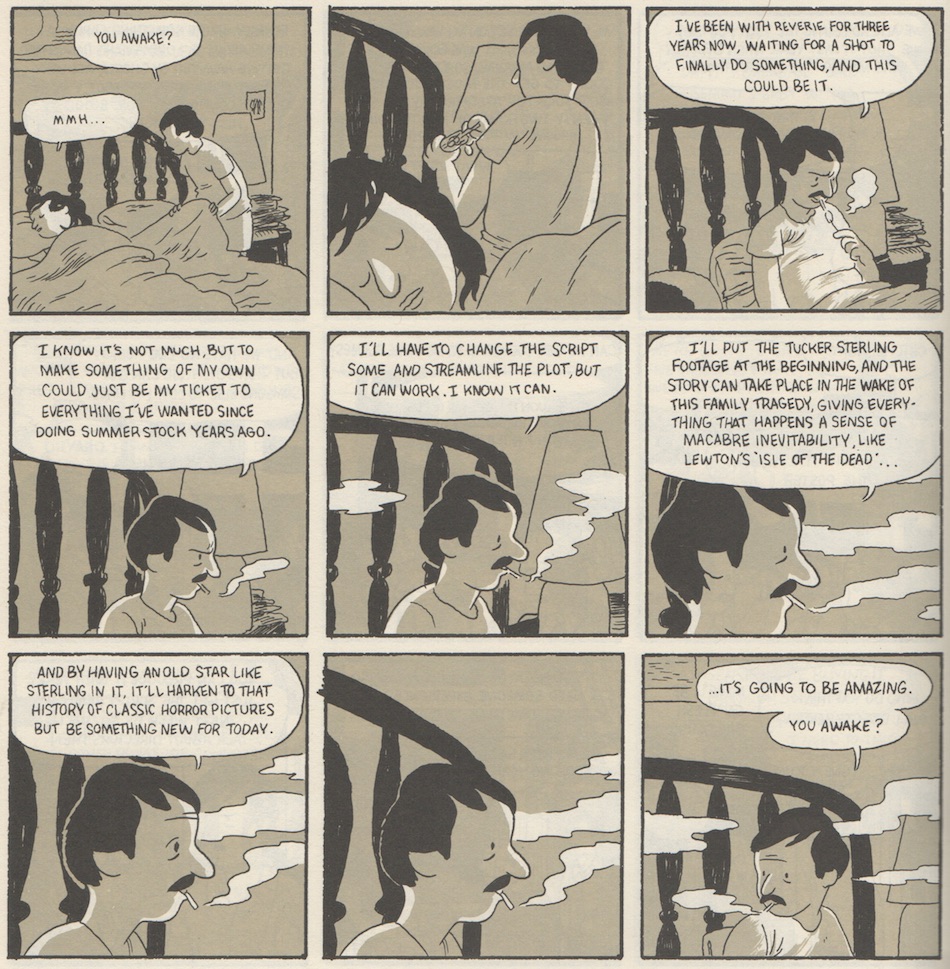

Each member of the large supporting cast is vivid enough to drive home how distant they all are from each other. If a film is an exploitation picture because neither the actors nor the people behind the scenes achieve the cushion of celebrity afforded the A-list, it’s worth noting Joy is alienated from her labor as well: she dislikes movies, which she considers “phony” compared to the “real” of rock and roll, an opinion that clearly breaks the heart of Seymour, who believes that B pictures are the kind that really matter. Perce, the film’s leading man, has slept with his co-star before, and now speaks contemptuously of her. Oswald, the film’s first director, is an Antonioni fan who directs the actors to do scenes slower and gets fired for making something too boring to make money. Production manager Myrna is so valuable to Seymour that they might share a romantic connection, but she maintains a fidelity to her husband, off fighting in Vietnam, where his person would be subject to any number of unknown fates. After a scene of extended eye contact, with each person using the other's attention as the resting place for their own drunkenly reeling perception, her resolve weakens.

The toughness and will of Seymour’s wife Ida marks her as separate from all these movie people; she socializes with them, although she resents that they do not understand her as being Jewish in the same way they are. She goes home to New Zealand, on the other side of the world from California, and we’re treated to a large amount of her backstory, with a flashback revealing that her mother lost a child in the Holocaust. She has never mentioned this to her still-living daughter. It is a great tragedy, deepened by not being spoken of, which connects it to the rest of the book’s system of hurt nursed in a vacuum.

As in the Coen Brothers' film A Serious Man, there is a sense of Jewishness as a parade of sufferings and indignities that must be borne. You catch your wife cheating with someone else, and then it’s that other man who beats the shit out of you. The next scene shows you still married, your body curiously not much worse for wear. Like physical blows, the humiliations characters suffer don’t necessarily affect them either. Seymour gets a chance to direct his script, after the first director is fired, and then filmmaking wraps before he’s gotten all the footage he needs; the film is completed without him. This is the sort of event that is damaging in part because it augurs a failure that will be attributed to a filmmaker, and therefore tank their career, but the film succeeds anyway. Success, stumbled upon within these circumstances, means nothing, and so becomes, in its own imprecise way, another degradation.

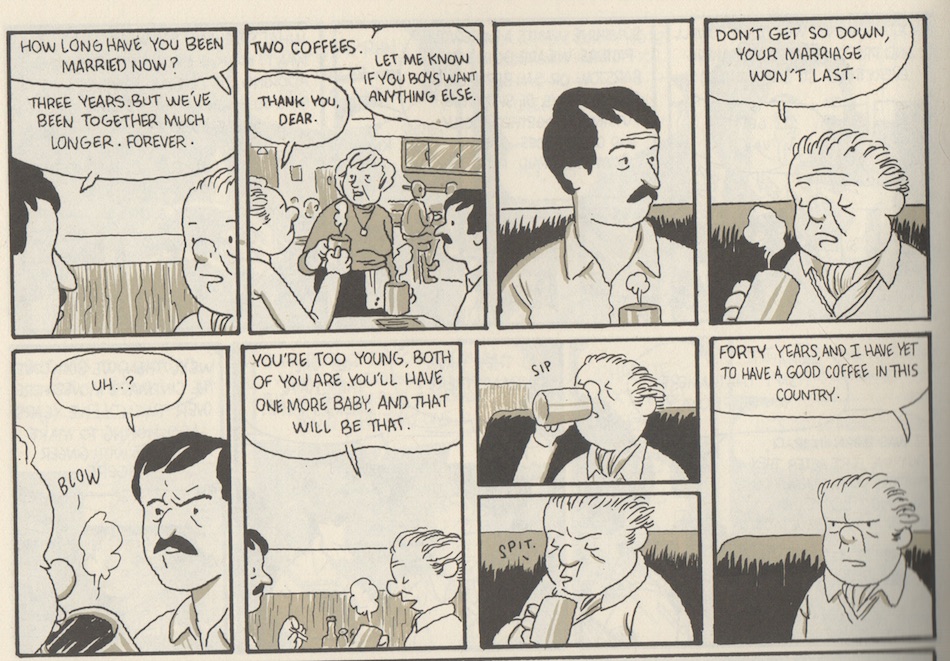

One of the things that defines horror is its sense of inevitability, that fate cannot be evaded once wheels are in motion. The most violent and fucked-up thing that anyone does to Seymour in the churn of social interaction is to casually predict his future. There’s an air of projection when someone says his marriage will fall apart after he has another child, or that he will keep working for the same film company until he’s out on his ass, but the bounds of the narrative means we accept the likelihood of these oracular pronouncements as what will happen after the book ends. Nothing suggests the possibility of a happier alternate ending.

The very idea that fate might exist and is inescapable spits in the face of dreams and ambition, which is what the movies are all about. The films being made by these characters are B pictures, but the '70s time period implies that everyone has artistic ambitions of one kind or another, and are creating journeyman work to learn their craft before moving on to other things. Jonathan Demme, for instance, clocked some time under Roger Corman, and the production of Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets involved editing already-shot footage into a new picture which might resonate with the times in which it was released.

I read Blood of the Virgin as it ran in issues #3 through #8 of Harkham’s single-artist anthology Crickets. The collected edition from Pantheon is set for release this week. Any number of alterations might be made between the serialization I read and the book’s final form, but I presume these will be minor. A few spelling errors I spotted will likely be corrected, but this won’t change the fundamental shape of the thing. A comic is a document of a series of decisions being made. As in life, the exact choices accumulate into their sum so quickly the flowchart of one into another quickly dissolves. This is what Blood of the Virgin is all about. Reading the book all together, these decisions of what is shown and how time is navigated resonate in a more symphonic manner than in single issues, where they just feel supremely pleasant due to their expert telling. The editing of this book, in a filmic sense, moves things along masterfully, lingering on character details enough for everything to come alive, but still move briskly.

There are pages I am editing out as I assemble my own cut of the finished book in my head. The ephemera surrounding the serial in most of the Crickets issues is largely inconsequential, although the covers were generally impeccable, with the cover of the concluding chapter in particular perfectly capturing the setting’s era through choices in color palette, logo typography and the wardrobes of figures depicted. Obviously, the few letters that ran in the pages of Crickets will not be included in the book collection, but the tone taken by those selected affirms Harkham as a rowdy boy, amused by impropriety - someone who wouldn’t kick Paul Schrader out of the online poker group for anything.

See also: Harkham’s association with Will Oldham, providing drawings for I See a Darkness, the record that houses the song of the same name, recently admitted by its songwriter to be about a friendship with Harmony Korine. Harkham also co-edited, with Ronald Bronstein—director of Frownland and a close Safdie Brothers collaborator—R. Crumb's Dream Diary. All the filmmakers within this orbit are avowed fans of John Cassavetes, and Seymour might well be named for, or dream-cast as, Seymour Cassel circa 1971’s Minnie and Moskowitz, with his ridiculous mustache. A greater leap of my own dream-casting has his wife being played by Jeannie Berlin, from Elaine May's The Heartbreak Kid and Larry Cohen’s Bone. The “zonked out space look” Oswald sees in Joy is to me exemplified by the Warhol Superstar Viva, who can be seen in Agnès Varda’s Lions Love or opposite Kris Kristofferson and Harry Dean Stanton in Cisco Pike. The precise flavor of Blood of the Virgin feels cast in this scabrous black comedy deep cut mold. The defunct bookstore Harkham co-founded, Family Books, worked with PictureBox to bring two Charles Willeford books back into print - one a memoir and the other, Cockfighter, a novel adapted into a Warren Oates vehicle directed by Monte Hellman. These books and films feel revelatory to encounter now, both because of their “could never be made today” quality and the sense that they were ahead of their time in a way that can only be appreciated by modern audiences. Harkham has made a work abundant in visual beauty, that’s nonetheless structurally unconventional in a way you’d only learn about from a Pauline Kael review compiled in a book with a sexual innuendo for a title. If modern audiences are as modern as they think themselves to be, they’ll see it for the real thing it is.