Norths is Alison McCreesh’s second book, a collection of postcards that she sent every day from November 2016 to May 2017. McCreesh, her partner, and their son spent last winter traveling North of the 60th parallel, visiting Finland, Russia, Iceland, Greenland on a series of artist residencies. Every day McCreesh wrote and illustrated a postcard, all of which are now collected in her new book, which was just released by Conundrum Press.

Norths is Alison McCreesh’s second book, a collection of postcards that she sent every day from November 2016 to May 2017. McCreesh, her partner, and their son spent last winter traveling North of the 60th parallel, visiting Finland, Russia, Iceland, Greenland on a series of artist residencies. Every day McCreesh wrote and illustrated a postcard, all of which are now collected in her new book, which was just released by Conundrum Press.

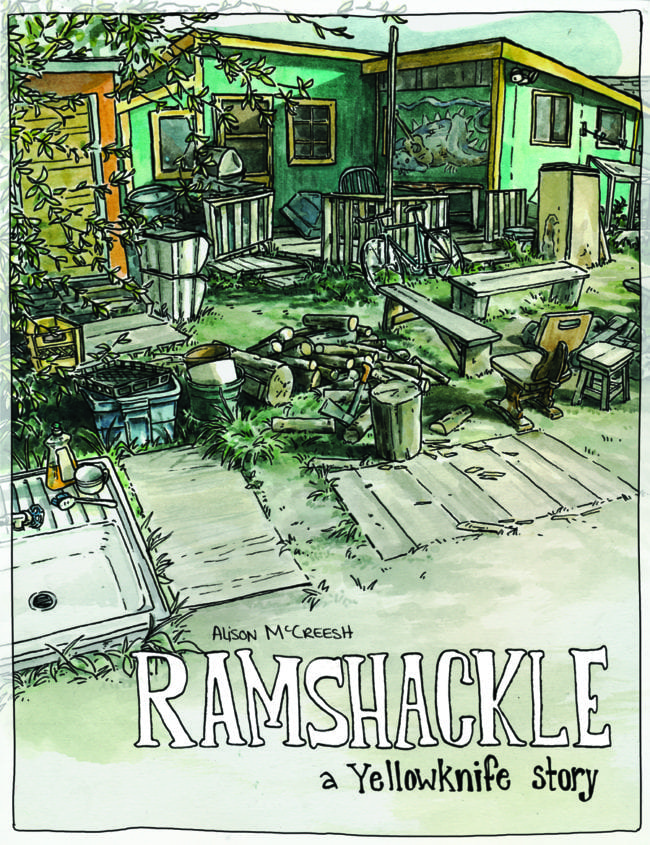

McCreesh’s previous book Ramshackle was also about travel. McCreesh and her partner after school bought a van and drove to Yellowknife, in Canada’s Northwest Territories. They spent the summer there, before leaving on a trip through North America, before returning the next year, where they continue to live. Ramshackle was a look at the summer the two spent in Yellowknife, but also a book that sought to capture some of what made the place so unique and colorful. In both books, McCreesh is trying to capture a sense of place, while always aware that her perspective is limited. Norths is fascinating, because McCreesh admits that the speed and shape of the project meant that there’s more from those experiences and places that she wants to consider and reflect on and write about, even as the format allowed her to capture something spontaneous about those months. McCreesh and I spoke via skype while she was pregnant with her second child about both books, working as an illustrator and fiber artist, and this idea of North. We edited the piece together after her son was born. - Alex Dueben

I’ve always traveled a fair amount and it’s always been a big part of my writing and art practice. When I go traveling I keep travelogues or sketchbooks or draw comics. I try different forms, but what generally happens is that I run out of steam about maybe ten days in. [laughs] It's almost inevitable once the novelty wears off and everything stops being to me new. Part of the idea behind this Norths project was to find a strategy that would force me to draw and write daily for the entire trip. I pre-sold original postcards for every day I would be gone. Each day, I would have to write and draw a daily postcard to someone and I would be on the hook because people had already paid for them. Beyond forcing me to commit, I also thought it would be a good way to get people engaged. Everyone likes getting mail.

At the same time, I was also trying to fundraise a tiny bit, although it wasn’t the smartest of fundraisers in terms of money generated for the effort and time invested. [laughs] By the time I bought the watercolor postcards and then mailed them, to say nothing of how long they actually took to create, it really wasn't lucrative.

I was going to ask about the logistics. Doing the art, writing them, getting a good scan for the book, mailing them from overseas must have taken a lot of time.

Oh yeah, it was a terrible idea in many ways. [laughs] In all the different countries, the official reason for my visit was to be an artist in residence. I had all kinds of commitments. I was supposed to be making art and I was supposed to be working on an exhibition and, depending on the residency, I was giving workshops and artist talks. The postcard project was a sideline, something to work on in the evening. I don’t know what I thought. I guess I was thinking back on other trips that were more about hanging out. Travel travel, not work travel or family travel. I should have known better.

When you travel and you don’t have a kid – or you have a sleeping baby – you wait for a train and you have time to kill, so you sketch the waiting room. I thought that's what I’d be doing with these postcards. I’d be having coffee and draw what I saw out the window. Of course though, you can’t do that with an 18 month old. There’s no resting and sketching casually as you kill time. There isn't really time to kill!

I also simply underestimated just how long each postcard would take. I initially thought that the drawings would be less elaborate. More of a quick sketchbook style but then I became more and more ambitious. Likewise, I hadn’t factored in how long writing them would take. I assumed my messages would be brief “Chilly today, Hope all is well!” But then I got caught up in the writing. A lot of thought went into the content and trying to get it concise enough. It’s a really good exercise to be constrained to such a small amount of words. A postcard is pretty tiny and even if you get rid of the polite bits on each end, you still don’t have that much room. I wanted each card to stand alone to a degree, so it made sense to the person getting it, but they needed to build on each other so that they could be read as a book.

So is the book the actual size of the postcards you made. How was it working at 5”x7”?

The 5x7 part was fine. It was good to be limited in how long I could write. No complaints about the actual size. I’d keep that part the same. [laughs]

In one postcard you go through your schedule for the day and wrote that you were working constantly but never for that many hours at a time.

In one postcard you go through your schedule for the day and wrote that you were working constantly but never for that many hours at a time.

That was how most of the trip felt. Work and also travel and residency logistics. We were at each residency for a month or even two months, which sounds like all the time in the world. In practice though, it wasn't that long. There was always travel, settling in, long-weekends and lord knows-what to reckon with. Though the residencies would officially start on the first of the month, it would be the seventh before I really started on anything. And then the next round of logistics would be around the corner again, and those logistics were terribly time-consuming. Even though it wasn't backpacking and moving every day, there was a lot of planning getting from one place to the next. Traveling from Russia to Greenland, for example, had a lot of steps and stages. None of our travel went horrendously wrong but I was always worried it would. They were expensive flights so I didn’t want to miss one. And in Russia there were things like visa limitations to reckon with. I didn't want to accidentally overstay. There is more of an imperative to get everything planned well when you have a toddler in tow. A lot of evenings were spent planning instead of relaxing or drawing postcards.

Getting to Greenland from Russia was a big endeavor.

It was a lot to organize. Once in Greenland, we did end up seeing our plans changed due to weather, but that part was fine. I spent two years traveling all over Nunavut for work so I'm used to tiny planes and blizzards and cancelled flights and everything just being casual. You’ve got no control over it, so you just sit around and grin and bear it. Once you’re stuck in weather, you’re stuck and I can roll with that. It's the more urban legs of the trip that had me more stressed. I’m not normally that anal about planning, but having Riel with us made me go overboard trying to figure out details. We were getting into Copenhagen late and each step seemed important to get right. How do we get from the airport to the hotel. How do we buy a metro pass. All those little things.

Because of the toddler, I ended up spending a lot more time planning than I would have otherwise.

Reading it I kept thinking about all those things that you do while backpacking where if you get in late you’ll walk around and then sleep at the train station or something. But with a toddler, you can’t do that.

Yes. And suitcases make everything clumsier! Normally I traveled with a backpack, but this time it was winter so we needed more gear. And the kid was still in diapers so we had cloth diapers. And we had all the art supplies because I was going to these residencies. We also had a backpack to carry Riel and a stroller and more snacks and more changes of clothes and small toys and lord knows what else. Even if we used to be pretty good at traveling light, all of a sudden it wasn't light anymore.

One thing that stood out was the strollers in Russia that have skis.

[laughs] It’s funny that you mention that. Recently, I’ve been thinking about what should have talked more about in the book and one of them is those strollers.

Norths wasn’t like writing a regular book where I would plot the whole thing out and see what I wanted to talk about and what was most important and how I would tie it all together. If I'd had the luxury of hindsight, I'd have given way more space to the winter strollers! They had skis and they had wheels to flip down to cross the street or go inside. There was a slew of different designs and it would have been worth drawing them all with explanations. We loved them in the moment and talked about them a lot but they only get a quick mention in the book despite them being so noteworthy to us. I’m glad that you noticed!

You mentioned in the book’s introduction that when planning this circumpolar trip, you wanted to stay North of the 60th Parallel. What does this idea of North man to you?

I have a hard time talking about the idea of North or where North starts or what North is, because North is so relative. The further North you go, you always find there’s someone further North than you. No matter how far North you are, you’re always South of someone, I like to say. [laughs] I have been far North – way up North of the Arctic Circle, what basically looks like the top of the world – but even then, there were places further North.

In Canada we have provinces and territories. The 60th Parallel cuts across Canada and marks the end of the provinces and the start of the territories. The Three territories are Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon. We live in Yellowknife, in the Northwest Territories. Up here lots of things are “North of 60”. It’s kind of a branding thing that people brag about. Because we use that expression so much, the 60th parallel was a good parameter in terms of defining where the North starts for the purpose of this trip and book. I found out that depending on where you are, being North of 60 doesn’t always mean much though. In Finland, for example, the whole country basically starts at the 60th Parallel so being at the 63rd parallel doesn’t make you Northern Finland. In Iceland, there isn't even a thought for the 60th. Still though, for me it was my North.

As you said, in Finland you were at roughly as far North as Yellowknife, but they don’t think of themselves as North at all.

Totally. It was interesting to see who identified as being in the North. In Finland where we were was simply the centre of the country. In Russia I don’t know that they used the 60th Parallel as a reference either because geographically it doesn’t intersect their country in any significant way, but they identified as North. They weren’t near the Arctic Circle, but they were North of St Petersburg and Moscow, so they felt North. At the same time, we were in a big city so it didn’t feel North to me the way Yellowknife feels North. In Greenland we were on the Southern tip on the country which is basically the 60th Parallel. It was the Southernmost place we went but it was the place that looked most like what you'd expect of the North – no trees and fjords and just snow and rocks. That was another interesting reminder of how it’s not just latitudes that impact the geography or what looks like North.

For the residencies, what were you doing?

I had committed to making a new body of fiber art. Big wall hangings mostly and some animation. I was recording sound and video to use later, but mostly big studio work.

You have a vimeo page which has a short excerpt of this longer piece, and you mention now and again in the postcards about trying to get sound and video. Besides fiber art and comics what are you doing?

As part of the residency series I had grand plans. I was trying to find a way to expand my fiber arts practice and give people an immersive experience of the Norths we visited. For each place I was going to record soundscapes and make these ambient type animations with fibers. In terms of being time-consuming, the only thing worse than comics is animation. [laughs] When I was planning this, I thought I had all the time in the world so it seemed feasible. I did it in Finland but then it was just too time consuming. I did continue to record sound and video to have all that documentation in the hopes that someday I would get more studio time again and find ways to bring it all together. Now that I’m home though, there’s only so much time in a day. My bread and butter work is illustration work and the fibre work has been forgotten since we got back. I freelance and so since being home I’ve mostly been focused on illustration and earning a living. The sound and video documentation are sitting on a hard drive waiting for me to find time again.

This trip took place last winter. Has it played a role in what you’ve done and been thinking about the past year?

No. [laughs] For the past ten years, I’ve bounced back and forth between comics and illustration and fiber arts depending on opportunities and timing. Since I got back, I've mostly been busy with the illustration. I’m sure [the trip] must have influenced me somehow, but when we got home we were so tired. I had bit off a bit more than I could chew with this entire Circumpolar endeavor so I was just so relieved to get home. There was no energy left to look back on the trip. And from a practical standpoint, I had to get back to income generating work again. I had gotten grants for the travel and residencies, but once we were back it was time to pick up where I left off. In a way, it was like the trip never happened. It was the same season as when we left. We left in the fall when the first snow was falling and we came back the beginning of May and there was still snow. [laughs] The vibe was similar and we were ready to be in our Yellowknife life again. I think now almost a year later I’m more ready to reflect on it and look back. I would like to make more work that touches on the trip differently.

Your book Ramshackle was about Yellowknife in summer and Norths is about winter elsewhere. Winter is when the North shows some of its true character. Your book about Yellowknife was about when it’s atypical and your second book is about leaving it to go elsewhere.

It’s funny that you mention the season thing. When I first brought Ramshackle to Andy Brown at Conundrum, he commented on how it was surprising that there was no winter in a book about Yellowknife. People expect winter in stories about the North. At the same time, people thought we were crazy to do this big circumpolar trip in the winter. It made sense for that reason though. To me it seemed like the North would be the North in the winter. Northern summers are magical in their own right with their combination of mosquitos and no darkness. [laughs] But what we think of as more stereotypical North, or what we expect of the North, is the cold and dark and miserable-ish. In a good way.

You’ve always traveled a lot. Ramshackle is about how you traveled from Quebec to Yellowknife and then you kept traveling after that summer. Where did you go?

Coming to Yellowknife didn’t seem that ambitious. It was the first time Patrice and I traveled together, but we had traveled separately across Canada more than once. When I was seventeen I hitchhiked to B.C. and spent all summer hitchhiking around and living in my tent and picking cherries. The summer before I came to Yellowknife I hitchhiked up to the Yukon, my first northern adventure. Patrice had also had similar Canadian travel experiences. By comparison, driving up to Yellowknife seemed fairly mild. [laughs] We came to Yellowknife because I’d had a great time in the Yukon the previous summer. We thought we’d try a different North. We were pretty confident there would be work and it would pay better than out East. We were hoping for summer jobs that would generate a fair amount of income but in a context where it was okay to be transient and passing through. And coming North made it more exciting than just finding summer jobs back home. The plan was always we’d work for that summer, have a bit of an adventure, save up money and then go around North America. After we spent that first summer, had a blast and fell in love with Yellowknife, we decided this is where we were going to live – for maybe two years we thought at that time - but we still wanted to keep going with our big master plan. We spent time in B.C. and then a fair amount of time in California. We went to Mexico and spent several months there as well. By the time the next spring rolled around we went back to Yellowknife and it became home.

At the end of Norths you seemed to be questioning your work-life balance. Some of that is because your art got lost, but have you come to any great answers?

No. [laughs] I don’t want to be overly philosophical about it. I have no big answers, but travel is a good reminder that it is people and experiences that you remember. Not necessarily the crazy experiences like climbing a big mountain, but small moments of hanging out and spending quality time with people. I'm trying to remember that for my sedentary life as well. Maybe as you get older and have kids your priorities shift a little. I'm trying to bear in mind that working a bit less might be for the best. Maybe it’s okay, for example, to just have a book come out every four years instead every two and a half years. Small things like that. I don’t know that I’m actually applying this. [laughs] It’s something I try to give more thought to anyway. Then again, comics are just so time consuming that, to a degree, you have to be all in if you want projects to actually happen.

I just interviewed Craig Thompson and we were talking about Carnet de Voyage and travel writing and trying to capture that immediacy. In Norths you found an interesting way to capture that immediacy while you traveled.

The immediacy is definitely a great part of drawing and journaling on the road. I have stacks of unpublished sketchbooks and notebooks where I strived to capture it. This postcard book has some of that, but it's not quite as spontaneous. Because of the format, I had to be a bit more deliberate than organic. Still, it was created daily without all the plotting that would go into a book that looks back the way Ramshackle does.

Deliberate or not, like I said earlier, I think I’ll have to do more writing about this Northern travel with hindsight. I feel like the everyday postcard work inevitably misses some stuff that would have been important and dwells on things that weren’t that relevant.

It’s funny how you travel to these places that seem exotic, but when you’re there you’re doing day to day stuff. I find that interesting in general. I like Guy Delisle and I like his juxtapositions of a place that seems so foreign but at the same time a lot of the humor is in the very small things. A lot of the angst or the small personal things aren’t even related to where you are that much. Life goes on.

He’s in Jerusalem or Myanmar, but he’s trying to find a playground to take the kids and go shopping.

It makes the places very relatable in that way. I adore reading his books for many reasons, but what I like most is how they put a very human face on places that I don’t know that much about beyond a slight acquaintance with the political context. Guy Delisle is an outsider looking in and there’s no pretense to being otherwise. He’s a Westerner there with his kids going about muddling through daily life. It’s more deliberate and less spontaneous than Carnet. A different kind of travel writing. I enjoy both!

You talk about some of these things, about how meeting people changes what you expected, in the Russia postcards a lot.

I probably dwell on it more in Russia because that’s where we had most, or least, expectations. It was the place we knew least about. We like to think that we don't have too many preconceived notions or ideas, but of course we do. I was an outsider looking in and we were only there for two months so it remains superficial in many ways. I don’t really touch on the broader political context, though of course I knew there are all kinds of human rights problems going on. It’s not so much that I was shying away from that, it’s just that we were there with our toddler and the broader issues weren't in our face at all. It wasn’t something that came up in conversation. Maybe I should have made it come up in conversation, but I didn't.

A good example that demonstrates some of our preconceived ideas is the snowpants. We had snowpants and all kinds of winter gear with us when we went to Finland because so much of what you see about Scandinavia is outdoorsy alternative progressive and left leaning. Our experience of Finland was different. It was in many ways like a lot of smallish ruralish towns across the world. People liked loud motor vehicles and it didn’t seem that hippie or alternative. Similarly, we had thought people would be super friendly, but hey weren’t necessarily. And of course, why would they be? We weren’t there that long. Not that they weren’t nice, but I think Finns are generally a reserved people. We were in a small town and by the time we found a playgroup to go to and went a few times and people warmed up to us and invited us over for coffee, that had taken weeks and then it was time to leave again. My point is that we had snow pants and outdoors stuff because we thought we'd get invited to the cabin and to play outside a lot and that didn't happen. So when we were shipping things home before moving on to Russia, we mailed the snowpants home. We thought that in Russia no one’s would invite us to do anything because we thought the Russians would be gruff and there would be a distance with foreigners. It turned out that mailing the snowpants back was stupid. In Russia we did get invited to go snowmobiling and and to go to the cabin. People were nice and welcoming and did invite us to do stuff. Not to take away from the other countries we visited because the context of teach residency was so different, but we were mistaken and Russia was one of the places where we felt most welcome.

You talk about how each place and each residency was different. How places were familiar and unfamiliar in unexpected ways. It was an adventure in many ways.

[laughs] I guess it was. And so not an adventure in others. It was just day to day life, too. Not that many big crazy things happened. We just puttered along and went to work and tried to entertain the kid and made dinner in different places.

When we were setting this up, you mentioned that it was your son Riel’s birthday and I thought, I know this, I just read about his last birthday in Norths. [laughs]

[laughs] That’s six months of our life there. That’s the funny thing about these autobiographical books and projects. Here in Yellowknife, so many people know so much about our first summer up here and small factoids of our life because of Ramshackle. It's one of those books so many people have read here, and especially gifted to relatives. It seems to be a good way for a lot of people to explain why they moved here. Yellowknife is a fairly transient place and though not everyone moves up and lives in their van, everyone's story is a variation on the theme. It hits closer to home for those who choose to live in shacks and houseboats, but there's also a commonality with people who come for a government job and buy a house. There's the shared story of moving here and falling in love with the town. Yellowknife seems so far way that friends and family are often a bit baffled when people choose to move to Yellowknife, so Ramshackle gives some context.

I always feel weird assuming I know people who make autobio work, but I do.

You do know stuff about us.

Well, yes and no. I know you in the same way that after reading Ramshackle, I know Yellowknife. Though I do really want to visit Yellowknife. Probably in the summer.

[laughs] Come in March. We have the Snow Castle and the Northern Lights and it’s not quite as cold as in the middle of winter. There’s no mosquitoes. I always recommend March. After the dark and cold of January and February, March is a little more bearable.

I did love reading about houseboats in Ramshackle.

[laughs] We lived on a houseboat several years ago. That was back when I was still being diligent about my daily journaling and comics and I documented the experience with a lot of that immediacy we discussed before. My first epic plan for a graphic novel was about the houseboating life. I got about two thirds done, but it never got completed. There was a lot of interesting stuff about the houseboats. The commuting. The in-between seasons. All the systems. The houseboats here are different to the ones that are docked and accessible like in Vancouver or Seattle. The ones in Yellowknife Bay are away from the shore and anchored. It’s a slightly different spirit of houseboating with all the logistics and challenges. For example, your anchor need to be strong enough because you don’t want your house to suddenly drift. [laughs]

And I’m sure when the lake starts to freeze, people have to make sure that the house doesn’t freeze at an angle.

They have to freeze level or it's a long winter. Freeze-up is different every year – sometimes it’s fast, sometimes it’s slow, sometimes it’s windy. In the winter when you’re frozen in, you can drive to your house so it’s a bit more like living on land. Not quite though, of course. People have a generators to reckon with and though and a fair amount of people have propane back-up, they mostly heat with wood stoves. You don’t want the fire going out though because when it gets below -40, propane gels. It's the little things that make day to day life a bit more exotic – or complicated, depending on how new it is to you and how exciting you find it. Though some people live out in cabins out in the bush, these particular houseboats are basically in town. A lot of people have day jobs that means rushing home for lunch to make sure the house hasn’t frozen up and to put another log on the fire. I guess I don’t think about it much anymore, but initially I saw a lot of material for a comic in that contrast. Ten years ago in the early days of smart phones – early to me anyway – it would blow me away that people had these fancy devices but then they didn’t have power at home. I like to find the humor and the quirks in the small things.

That’s how you portray Yellowknife. It’s an interesting contrast between the ordinary and the strange.

That's definitely how I thought about it for years, and maybe part of what I fell in love with. You and I are talking about this now and it makes me realize how I don’t notice these things anymore. That's one of the good things about the travelogues or taking a lot of notes when stuff is new, if you wait too long you stop seeing and noticing the quirks. You get used to things and they stop being noteworthy. It's good to have incentive to keep keep journaling daily, in some form or another, even after the novelty has seemingly worn off.

At the end of Norths there are a few postcards from Yellowknife. There’s one about one of our friends who has a kid the same age as Riel and she has to commute from their houseboat. It’s almost breakup so they have to paddle across the “moat” because the lake has started to thaw around their house. The kid is in a lifejacket for that part of the crossing. Then they’re on the frozen lake and they use a sled to pull her to the shore. It's still cold on the ice, so she needs to wear a snowsuit. But then it’s spring on land, so they're biking to daycare and the kid needs a helmet. It’s regular life – but a little more complicated. A little more exotic – or annoying – in the day to day.