Charles Hatfield: From the sound of it, Clyde Fans should be an epic: a mid-twentieth-century family story spanning some four decades in the life (and death) of a company inherited by two sons from a wayward father, a business vulnerable to technological and social change and thus ultimately made obsolete. Firmly set in postwar to late-century Ontario, and rooted in certain kinds of Ontarian landscape and a (then optimistic, now pitiable) commercial culture of nonstop go-getting salesmanship — an eager, scurrying, small-time capitalism — Clyde Fans seems determined to chart how a changing world looks from a particular vantage point. Culturally, it’s very specific, and there is so much that might be done to show how various people lived in and made that culture. The lives of Abraham and Simon Matchcard, mismatched brothers working for one too-long lived business, would seem to be an apt vehicle for depicting change in the world (or at least the Ontario) at large. Though mundane, Clyde Fans covers so many years, and has taken so very many years to complete and collect in book form, that the temptation to greet it as Something Big, a monumental work, is hard to resist.

The thing is, the collected Clyde Fans, to me, despite its physical heft, feels like a small story, or rather a meditative visual poem. It doesn’t feel big. It’s intimate. In fact, it’s more than intimate: it’s a closed world, a microcosm, much like the Clyde Fans building that encloses so much of the action. Seth, in rounding off the story, does what the Matchcard brothers do: he turns inward, tightening scope, excluding much of the social world whose changing nature might lead us to expect, well, an epic. This is a story about two recluses, each clinging to the Clyde building for his own reasons, one a go-getter perhaps tragically replaying the sins of his hated father, the other nursing their dying mother and embracing darkness and solitude as a relief from the world’s pressure, but both crawling inside themselves and seeking or succumbing to oblivion. The book itself mirrors their retreat, winding down and disappearing down its own ostrich hole, ending with a rejection of the larger world that ambiguously teeters between tragedy and affirmation. Before this, the story climaxes with a rapturous flight, a sort of astral journey, for brother Simon: a vision carries him across a dark landscape and in and out of buildings marked by obsolescence and decay, toward an understanding or at least an acceptance of the terms of his defeat. That transporting vision has everything to do with Simon’s failure as a salesman, an earner, a striver, but he disconnects from all that, withdrawing into his own pacific, grandly despairing vision of the world, one focused on a kind of entropic inevitability that he embraces, or, at any rate, no longer cares to resist. By story’s end, he is beaten but beatific (or maybe he’s just gone crazy). His overbearing brother, Abraham, is just beaten. I couldn’t decide if the ending was supposed to affirm the formerly anxious, socially withdrawn Simon in his solitary ways or if I was supposed to be terrified at what the brothers had given up.

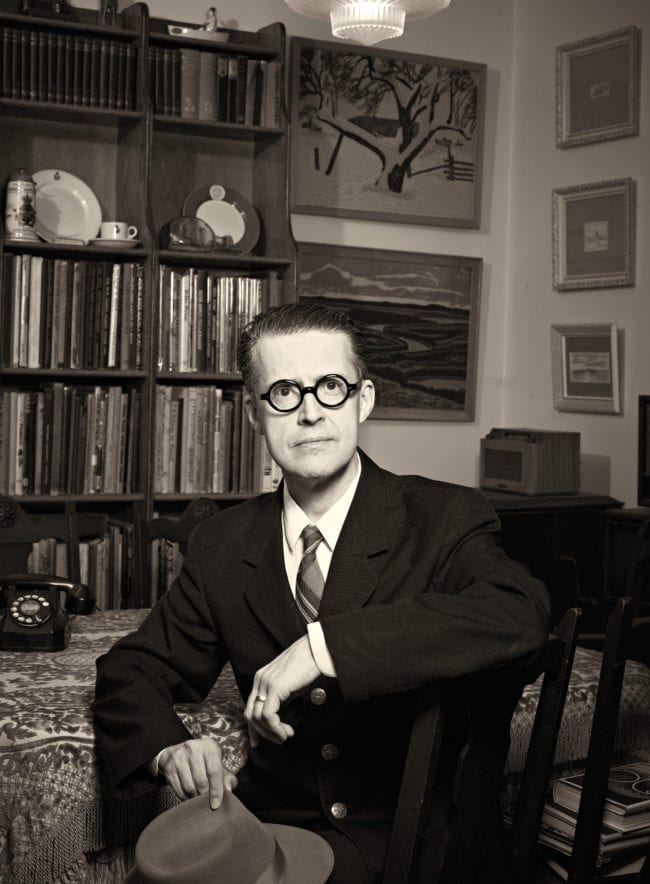

Formal unity would seem to be the saving grace of this insular book -- that and beautiful drawing. The drawing certainly is beautiful, stem to stern, but formal unity isn’t quite what’s offered. The early chapters of Clyde Fans are rendered with a wispier line and lettered with a frailer hand; they are startlingly different from the more recent chapters, in which bolder, heavier drawing and sturdier, darker lettering take over. Seth has changed over the years, and in the twenty-plus years leading to Clyde Fans the book, his lines and forms have thickened, gotten blockier and more rugged, leaning toward Peter Arno maybe in their robustness. He’s just gotten stronger, artistically — better. I like the way the style evolves, but a flip back and forth between early chapters and late ones gives me a bit of a shock. The history of a developing cartoonist is here: Clyde Fans is Seth’s fossil record.

Formal unity would seem to be the saving grace of this insular book -- that and beautiful drawing. The drawing certainly is beautiful, stem to stern, but formal unity isn’t quite what’s offered. The early chapters of Clyde Fans are rendered with a wispier line and lettered with a frailer hand; they are startlingly different from the more recent chapters, in which bolder, heavier drawing and sturdier, darker lettering take over. Seth has changed over the years, and in the twenty-plus years leading to Clyde Fans the book, his lines and forms have thickened, gotten blockier and more rugged, leaning toward Peter Arno maybe in their robustness. He’s just gotten stronger, artistically — better. I like the way the style evolves, but a flip back and forth between early chapters and late ones gives me a bit of a shock. The history of a developing cartoonist is here: Clyde Fans is Seth’s fossil record.

Daniel Marrone: Your comments about the insularity and formal unity of the book got me thinking about the way in which Clyde Fans grapples with an almost metaphysical question: How far are you willing to extend your circle of reality?

For Abe and Simon Matchcard, the answer is: Not very far. Their reality doesn’t seem to extend past the property line of the Matchcard family home (which also comprises the Clyde Fans office and storefront). Even though Abe doesn’t actually live in the building until late in life, he frequently says things like, “It’s only in here that anything ever felt real. Out there everything was empty and hollow.”

It strikes me that there’s something about Seth’s comics that really is meta-physical, in the sense that they are physical objects – carefully constructed book-objects – which are about objects, about physicality. Buildings, fixtures, appliances, products, personal effects, mementos, assorted bric-a-brac: Clyde Fans pays special attention to these objects, to say nothing of Simon’s various collections. And in physical terms what objects mostly do, as basically every aspect of Seth’s work makes clear, is obsolesce.

The most obvious collection is Simon’s collection of novelty postcards. “Folksy photographic manipulations,” they feature images of men dwarfed by the products of a surreal harvest, apples the size of boulders, squashes as tall as trees. Simon explains that in their “re-ordering of reality” the photographs manage to thwart time in a way, showing a “frozen place” detached from the temporal world.

As you say, the change in drawing style over the course of Clyde Fans is almost alarming, in part I think because it testifies to the passage of time – “real” extra-literary time.

Tom Smart: I like the way that the theme of paradoxes in Clyde Fans has surfaced so quickly. Seth has given us a strangely immersive dialectic in the sad stories of these two misfit brothers. Big and small, inside and outside, real and surreal, sane and crazy, these and many other polarities give the story its tensions and, for me, make it a so satisfying, if terrifyingly grim, read. I grew up in London, Ontario in the late '50s/early '60s and recognize as true not just the types represented by the brothers, but also the crushing….whatever you call it -- culture, norms, beliefs, defeatism. Existential vacancy was so a part of my consciousness growing up in this particular Palookaville. In this alone, Seth is spot on.

I read the episodes as they were serialized in Palookaville, so the passage of time was an important part of my reading experience that echoes beautifully in the story’s structure. When thinking about this roundtable note, and before re-reading the pdf we were sent, I let my mind drift back to the reading experience just to see what surfaced in my mind.

I was surprised by the thought that came forward. It goes against the innate paradoxes in the structure. For me, the whole story is a rich metaphor of a single consciousness parceled out into different, so-called characters and settings. The brothers represent for me foils for a single character, one complex psycho-system. The building reads for me as a richly imagined depiction of a cluttered consciousness. Abe and Simon are elements of the same guy who is telling a meta-narrative about holding on to something -- sanity (?) -- in an ever-changing world where nothing stands still.

I agree with Daniel when he points to the postcard collection as something to pay attention to. I think this is an important fulcrum in the story, but am not sure in what way. I welcome comments…

Barbara Postema: While reading the new, complete Clyde Fans, I got out my old copy of Book One as well, fifteen years old now, and one thing that struck me is how closely that book still resembled It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken. As Charles points out, now reading the old and new parts all together, one can really see the sedimented layers of style as Seth’s cartooning has developed. Later sections have page layouts reminiscent of George Sprott, while throughout, the graphic sensibility of Seth’s recent work in book design is now recognizable. There is a sense of everything coming together here, which makes it feel slightly deflating that it comes together to such a “small story,” as Charles says, such a small world built around the two Matchcard brothers.

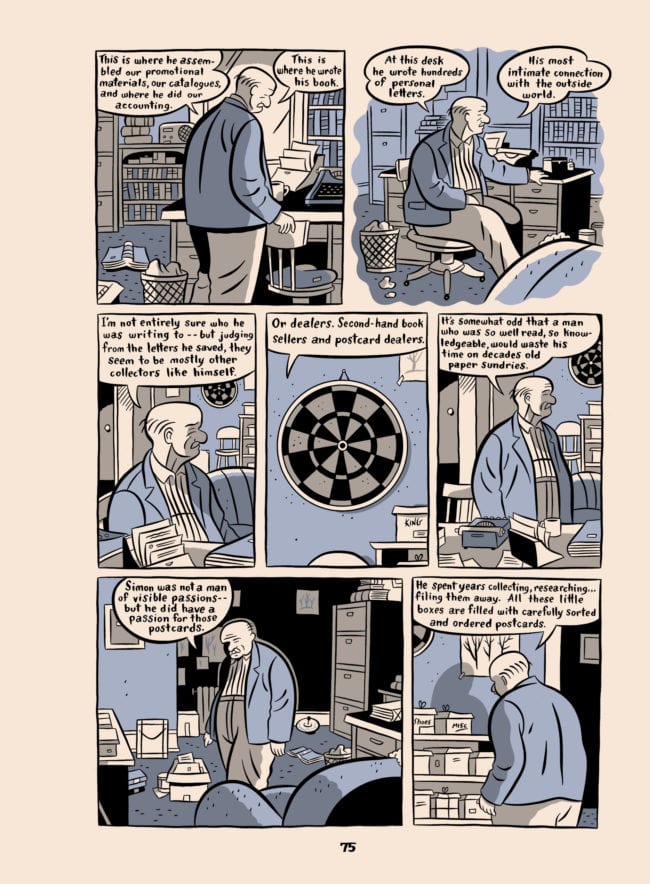

Another thing the new book does is insist on the realness of its world: in the expanded front matter of the book there are photographs of promo products for the Clyde Fans company, an ashtray and a calendar. Not only are these real objects, but they also include a real address, 159 Queen Street W., Toronto, Ontario. Much of the book takes place in fictional Dominion, but the heart of the story, the Clyde Building, is situated on Queen West, one of Toronto’s main streets. A few pages further, we come across several sketches on legal paper, included as if in a scrapbook. All these objects can later be attributed to Simon: As Abe wanders through the house in 1997, he reveals that Simon designed their promotional materials, presumably including the ashtray and calendar, and the sketch of the hilltop can be seen taped to the wall in the background (74-75). This hilltop is of course also the “enchanted place” where Simon experiences his vision or epiphany. That reality effect created by the ashtray and the sketches clashes with the increasing withdrawal from reality of the two protagonists. As Tom points out, the presence of the real with the surreal is one of the paradoxes of the book. The photographs also connect to time, both the time in the book—the calendar is for the auspicious year 1957—and the real extra-literary time, as Daniel calls it.

Another thing the new book does is insist on the realness of its world: in the expanded front matter of the book there are photographs of promo products for the Clyde Fans company, an ashtray and a calendar. Not only are these real objects, but they also include a real address, 159 Queen Street W., Toronto, Ontario. Much of the book takes place in fictional Dominion, but the heart of the story, the Clyde Building, is situated on Queen West, one of Toronto’s main streets. A few pages further, we come across several sketches on legal paper, included as if in a scrapbook. All these objects can later be attributed to Simon: As Abe wanders through the house in 1997, he reveals that Simon designed their promotional materials, presumably including the ashtray and calendar, and the sketch of the hilltop can be seen taped to the wall in the background (74-75). This hilltop is of course also the “enchanted place” where Simon experiences his vision or epiphany. That reality effect created by the ashtray and the sketches clashes with the increasing withdrawal from reality of the two protagonists. As Tom points out, the presence of the real with the surreal is one of the paradoxes of the book. The photographs also connect to time, both the time in the book—the calendar is for the auspicious year 1957—and the real extra-literary time, as Daniel calls it.

The world of the Matchcard brothers, the world of Clyde Fans, doesn’t exist anymore, the book tells us. But I feel a little like the world of Clyde Fans doesn’t exist anymore either. Its most recent setting is 1997, contemporaneous with when Seth started on this comic. Much has changed since then, and I am trying to figure out what this book has to say to the world today. The book touches on so much that is important: toxic masculinity, mental health, difficult relationships between the present and the past. Yet these things remain distant, hard to feel in an immediate way. I guess I am still trying to find ways to feel more spoken to by this book, which after all proceeds in direct address for much of the text. I feel like I may be missing some key ways of reading it and hope you have new ways of seeing it for me. Already I plan to go back and have a closer look at the novelty postcards…

Martha Kuhlman: This book pulled me in, and knocked me out. It has a strange, hypnotic intimacy that is charming and yet profoundly disturbing. It made me think of Miller’s Death of a Salesman—especially the beginning when we follow Abe through ordinary rituals as he narrates his life and rattles off his sales questionnaire from memory—and “The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock” at the end, when we are immersed in Simon’s reverie as he weaves through the empty city:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells

The power of this sequence in Clyde Fans (434-455) resides not so much in the words (alas, not as good as Eliot’s), but in the masterful orchestration of lights and darks, tiny windowpanes and the menacing outlines of abandoned factories, two-page spreads and pages sectioned into twelve identical square panels. Parts of this section also evoked the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, on one hand, and Kupe’s lighthouse from Hicksville, on the other.

Clyde Fans concerns memory, loss, nostalgia, among other things. It sparked two memories of my own: the first time I saw Seth in person at a comics festival in New York City in the fall of 2008, and the second time I saw him at a panel as part of "Comics and Philosophy" at the University of Chicago in 2012. Despite fishing around under the bed for my collection of random notebooks accumulated at various conferences, to my regret I couldn’t find my notes on either of these talks. But maybe that’s fitting, because the book is predicated on this notion of memory and replaying sequences in one’s head—whether they prove to be accurate or not.

On the first occasion, I had the impression that Seth had articulated something essential about comics that I had felt as well—namely, that comics can sometimes be structured more like poetry than like prose. And thus the subtitle for Clyde Fans, “a picture novel,” could just as well be a “picture poem.” For me, the interest in the book lies not so much in the “small story” but in how that story is told. My own bias shows here, because I’ve spent quality time examining Chris Ware’s work, and these two cartoonists clearly share a melancholy sensibility that is punctuated by meticulous grids, lonely protagonists, lost objects, and repetition. When I teach Ware’s comics, I cite a few lines from Ware to give students a sense of how to read his work: “What you do in comics, essentially, is take pieces of experience and freeze them in time. The moments are inert, lying there on the page… In music you breathe life into the composition by playing it. In comics you make the strip come alive by reading it, by experiencing it beat by beat as you would playing music.”

The second time I saw Seth speak, he was on a panel with Charles Burns, Dan Clowes, and Chris Ware. And I began to see the connections among their works multiply—the way, for instance, Burns uses black panels interlaced with scenes or simple colors in Last Look—is also present in Clyde. Ware and Seth construct elaborate fictional worlds, both figuratively and literally (in Ware’s Building Stories model and Seth’s Dominion set). All of these authors use a tightly controlled style beneath which lurks a reservoir of existential dread. I wouldn’t want to suggest that any of this is necessarily deliberate, but they follow each other’s work and seem to express a similar kind of disenchantment from the outer world in order to re-enchant an inner one.

Candida Rifkind: I sometimes wonder what it says about me that Seth’s comics speak to me, unlike Barbara, so deeply. I have very little in common with his main characters, and all my intersectional feminist training tells me to look for stories of the marginalized and the survivors, not those of aging middle-class white men who generally treat women (and each other) poorly. Yet, here I am. Perhaps it’s the paradoxes several of you have pointed out, those tensions between epic scale and intimate stories, big books and little men, the real and surreal, that I find fascinating. I should probably be repulsed by what Barbara calls the ‘toxic masculinity’ of Abe and Simon, but Seth never asks us to sympathize with his characters wholeheartedly. The noirish, cinematic compositions and shifting narrative perspectives combine with the clear, increasingly sturdy line work of Clyde Fans to always keep us at a distance, as though we’re either watching a drama play out on a stage or an experiment develop in a life-size petri dish. I feel neither affinity nor deep affection for Abe and Simon, but I am curious about their inner lives and their voices feel familiar. There is a pleasure in this extra paradox of the closeness and empathy Seth elicits for characters who are by all reasonable measures unlikeable and uninteresting.

Without diminishing their eccentricities, Abe and Simon are as much types of men, representative of a specific time, place, and culture, as they are distinct personalities. And so the theatrical and scientific metaphors I use above are deliberate references to the nineteenth-century English novel’s experiments with social realism and naturalism, from Dickens to Thackeray, except that Seth telescopes the layers of mid-twentieth-century southern Ontario society through a tiny group of limited experience characters. Reading Clyde Fans as a complete edition, rather than in the Palookaville installments I’ve followed for years, it strikes me as a thoroughgoing critique of the society that warped these men, in different ways, and as a lament for the richer lives they could have led, the ‘what ifs’: what if their father had not been abusive? what if their mother had not been so dependent? what if Simon had been a good salesman? What if Abe had saved the business? What if they had each lived up to each others’ expectations?

The postcards are one of my favorite elements of Clyde Fans because, while they do suggest Simon’s dwelling in memory and his collector’s impulse to gather up and organize traces of the past, they are also just funny. Seth’s sense of humor doesn’t get enough attention, I feel. Or, to be more precise, his representation of what counted as humor in the past – these kitschy postcards – inserts visual gags in a way that tells us something else about Simon. Yes, he is miserable and lonely and reclusive, but he is dedicating his time to collecting and archiving old jokes, and isn’t that in itself kind of a funny paradox?

On the final pages, we see the origin story of this hobby, as Simon pulls the penny postcards out of his jacket pocket and laughs at the scenes of small men dwarfed by a giant chicken and pig, respectively. “If all the world were paper,” says the next panel, and of course all the world of Clyde Fans is paper, it is both a paper world and paper swirls around Simon whenever he walks outside. Maybe the book itself is one giant novelty postcard. But, the symbolic reading of the postcards needs to be accompanied by something much more real, as it were. Simon’s hobby is that of a lonely and introverted man, but it also joins him to a network of artists (he knows an awful lot about Silas W. Wilfred) and his “usual sources” of other collectors (211-12). The postcards are traces of pop culture’s past and Simon’s investment in them is both a diversion from reality and a connection to reality, at once amusing and sad.

Clyde Fans is, as several of you have pointed out, so much about the object world. For a Canadian reader, there is nostalgic pleasure in Seth’s attention to lost consumer culture in the backgrounds, from a bag from the now defunct Eaton’s department store to the iconic Ookpik souvenir owl (213). But there are also object traces of the unequal and unpleasant past, such as the racist minstrel doll onto which Simon projects harsh criticism (214). Clyde Fans shows us how objects can be at once desirable and detestable, a paradox emblematized by Simon’s relationship to the salesman’s sample case. But this is also a book about the loss of these objects, and, moreover, the loss of their loss to current memory.

This, I think, is what pulls me into the work. Clyde Fans is not just about the pastness of the objects, buildings, and people of the mid-twentieth century, it is also about the way even the traces of their existence are disappearing. As we see, the dark rooms, empty stairwells, and long hallways are part of “the beauty and solemnity … that comes with solitude, estrangement … decay” (453). The problem is that once the traces of their traces fade, we can’t see how they haunt us still.

Smart: I’d like to shift the discussion a little, away from the lives of Abe and Simon, and out into the landscapes beyond the office and homescape to the putter golf course. When I first encountered this place I found it startlingly true, even though it is a psychotic emanation from somewhere deep in Simon. Seth has an uncommon and uncanny way to express a reality that, for me, is even beyond surreal. It’s as if he has developed graphic devices that express not just loss, but catastrophic, existential loneliness. Madness?

And here is another kind of tension: between the visual vocabulary of a graphic novel that riffs on received ideas about hilarity, and explodes this iconography to an exponential degree in a frightening hysteria. When I first found myself alone in the putter golf yard, I sensed a kind of familiarity with it, although I don’t know when or where I was in that place. In fact, as I am trying to describe the feeling, words like “surreal” and “dreamscape” seem to be way too inadequate to capture the essential nature of the nocturnal hell that Simon is cast into. As weird as Seth describes it in such masterful visual language, it rings true for me.

I am trying to think of another artist (graphic or not) that is able so tellingly to describe such a soulless place. Maybe Frans Masereel? Maybe Miller Brittain? Given that the entire episodic narrative is part of a larger project comprising Palookaville, is Seth suggesting that at the end of the road is a weird portal that takes you even farther and farther along a bleak narrative?

Looking back at the narrative arc of Clyde Fans there is a kind of inevitability that a lonely man’s collapse is an emblem of post-war southern Ontario’s unfulfilled economic promise and spiritual vacuity. This is the place where Simon and the reader are tossed. As I read the novel’s parts, each throws a different degree of tonality on the characters and the reader, to the extent that the golf course is a southern Ontario nullpunkt.

Marrone: There’s a lot to respond to here, particularly in relation to what’s sometimes called Southern Ontario Gothic and the landscapes with which that literature is associated. As I gather my thoughts, I’ll stall by offering a dispatch from the recent Clyde Fans book launch at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

As you might expect, an array of local luminaries was in attendance: I found myself sitting directly behind Chester Brown and the Beguiling’s Peter Birkemoe; other familiar faces included Fiona Smyth, Jillian Tamaki, Michael DeForge, Joe Ollmann, and our own Jeet Heer. I’ve interviewed Seth at length in private and found him very personable and forthcoming – I never really thought of him as a public speaker. But during the launch, as he answered questions on stage, I was struck by just how appealing a presence he is. He was genuinely funny and self-aware, a natural raconteur, unassuming and rather effortlessly at ease.

One of the things he talked about that overlaps with our discussion here is the visual evolution of Clyde Fans over the years, which made it impossible for him to revise the earliest part of the book as he prepared the complete edition. “It’s almost like a different person drew it,” he said. “Something in the hand determines style, and that changes.” He also suggested a nearly allegorical connection between manufacturing fans and making comics, a craft he worried was becoming obsolete when he first conceived Clyde Fans.

But I am burying the lede: the most noteworthy part of the evening was the performance that preceded the interview with Seth. In lieu of a live reading – a staple of book launches but not a perfect fit for comics – there was a theatrical adaptation of Part One of Clyde Fans, with William Webster (from Toronto’s Soulpepper Theatre) as Abe Matchcard. I’ve always thought of Part One as a monologue or one-act play, so I was definitely looking forward to seeing it staged. (And, incidentally, the affinity between southern Gothic literature and certain strains of Ontario literature was first identified by a theatre critic.)

Maybe I’ve spent too much time reading Clyde Fans to objectively judge an adaptation of it – but the performance did not quite work for me as a piece of theatre. This is not an appraisal of the actor’s actual performance. More than anything else, it is my personal reaction to the distance between the fixed, silent, immobile medium of comics and the ephemeral, communal experience of live theatre. I’d be very interested to hear Jeet’s impressions.

Martha mentioned Miller’s Death of a Salesman, a natural association for me as well; another is Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross. To some extent Clyde Fans operates within this tradition, though I do not find it drearily melodramatic as I do Death of a Salesman, and Seth is not bombastic in the way that Mamet is. (However, there is that grandiloquent set piece in Part Two of Clyde Fans, in which fellow salesman Whitey invites Simon into his hotel room to show off his wares.)

Precisely because Mamet’s rhythms are so obviously removed from the world of Clyde Fans, he serves as an instructive point of comparison. If you look at one of his early short plays or monologues, even on the page you can see the language moving theatrically. By contrast, Seth sets down a measured cadence that suits the comics page, as well as the specific story and storyteller. While Abe’s opening soliloquy in Clyde Fans very effectively conjures a kind of private theatrical experience, it was definitely composed as a comics sequence.

Jeet Heer: I enjoyed William Webster’s performance as Abe Matchcard but also felt that the adaptation only works as a supplement to the book (fitting enough since the performance was part of the book launch). In fact, the one-actor play, which skillfully distilled the first chapter into a monologue (with considerable trimming and some moving around of the text) served to highlight how firmly embedded the words are in the comics. When we “read” the comics, we get not just the word but also the decaying, darkened, cluttered office/home that Abe lives in, a space that we come to imaginatively inhabit not just in the opening chapter but all through the book. Much of the clutter, the furniture and knick knacks, that Abe is immured in takes on a greater value over the course of the story as we learn where it came from and what it meant at different points in the family history. With the stage play, the background was minimal: a desk, paintings, a few other items. But this barely hinted at the suffocating memory-house that the Matchcards lived in. I think this is effect that could only be achieved by comics -- of not just the physical objects but also being able to flip back and forth in the book as we figure out how the physical objects came to be. Re-reading the book with a focus on those objects really changes the experience of Clyde Fans. I can’t quite think of anything comparable that can be done with visual memory even in sibling art forms like film (which don’t easily allow us to go back and forth).

Postema: Can I clarify something? There have been several references now to the Southern Ontario setting for the book, and I am not sure that’s right. Toronto is a main setting, and of course that is Southern Ontario. But the other main locale is Dominion, and according to the road sign Abe passes while making his way there to meet with Alice (p. 377), Dominion is past Barrie, Sudbury, and Timmins, increasingly far north. Apparently Dominion is 470 km from Toronto, further away than you can get within Southern Ontario. I was admittedly a little surprised to see this sign: I had previously assumed Dominion was in a similar area as where It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken is set, maybe somewhere near Strathroy. But it seems Clyde Fans moves beyond just Southern Ontario…

Rifkind: I noticed that, too, but all of Seth’s other comments about Dominion in Palookaville and in interviews suggest it’s in Southwestern Ontario. Is he being a trickster again, or is this just an inconsistency/convenience for the sake of the traveling salesman narrative?

I’m coming back to this question of place because I want to respond to both Martha’s association to Death of a Salesman and Daniel’s to Glengarry Glen Ross. I agree there is something about the theatrical to Clyde Fans, and these associations make sense, but my earlier training in Canadian Literature compels me to make a different literary association, namely to Alice Munro’s short stories. I think Seth is a fan (or did I imagine he once said he was?), but there are such intersections for me between place, sensibility, and narrative voice in Munro’s Southern Ontario short stories and Clyde Fans. It’s hard to pinpoint, but both manage to combine a distanced narrative gaze on local color while drawing us into psychological realism, and both pay great attention to the material and the mundane. The rhythms of Munro’s stories, their taut unfolding and delicate pacing, are also something I see in Seth’s layouts.

At the launch of the book in Winnipeg at the end of April, one of Seth’s many bons mots was that “"the size of the panels on the page is often more important than what is in the panel." This interest in page design makes me want to return, ultimately, to comics rather than literary associations. I have been thinking recently about the connections between Clyde Fans and Jeff Lemire’s Essex County. They couldn’t be more stylistically different, and Lemire really takes us into Southern Ontario Gothic proper, but the central story in the trilogy, “Ghost Stories”, is about the fraught relationship between two aging brothers and their various memory-steeped regrets. Reading them together would be an interesting exercise in studying how very different comics aesthetics can carry similar narratives of melancholic masculinity, and how crucial place and space are to both Seth and Lemire. So, maybe Dominion is in southwestern Ontario, or maybe it’s in northern Ontario, but Clyde Fans is definitely in the Southern Ontario of literary and comics imagination.

Kuhlman: “The size of the panels on the page is often more important than what is in the panel." I thought about this a lot as I noticed different patterns in the page layouts that had this musical rhythm and varied interpretations of time. For instance, there is the relatively sedate pacing of the nine-panel grid (440) (familiar to us from Mazzucchelli and Karasik’s adaptation of City of Glass, to cite a famous example); then the more dense twelve-panel composition (455); and finally the twenty-panel grid, where the viewer must slow down to see the development of shapes across the page. When Simon dreams while he’s on the train, he is transported back to his earliest memories (470) and the images become increasingly abstract, rather like a page by Richard McGuire, Lewis Trondheim, or the first page of Ware’s Jordan Lint. I am fascinated by the way that dark and light are manipulated to suggest inside/outside and drastic shifts in scale, reflecting the child’s perspective... It’s a geometrical display that tells the story of a mother’s comforting, and yet overwhelming or even sinister love; in this sense, it somewhat recalls McGuire’s animation “Fears of the Dark” (2007).

Hatfield: I like Barbara’s insight into the book’s lost worlds: both the depicted world of Simon and Abe and the comics world into which Seth brought Clyde Fans in 1997. It’s fitting that a book about obsolescence is itself a kind of time capsule. Yet, for all that, for all our comments about the book’s datedness, there is something very contemporary about Clyde Fans thematically — I’m thinking here of Candida’s observation about “melancholic masculinity.” Her comparison between Seth and Jeff Lemire is suggestive. Dare I point out that Clyde Fans shares thematic turf with the twilit world of current superhero comic books, which are, increasingly, studies in beleaguered “man”-hood? Lemire is one of the superhero genre’s laureates of trauma, of depression, anxiety, and fragile, distressed masculinity. Tom King is another. Comics like Black Hammer, Lemire’s Moon Knight or Hawkeye, or King’s Mister Miracle and Heroes in Crisis — these are largely comics about psychically damaged men. Academics have taken a keen interest in comics that lend themselves to trauma studies, but this theme now extends beyond autobiographical and autofictional work and into the superhero realm. (Actually, Frank Miller took us there with his traumatized Batman in 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns — but Miller had greater faith in an uncompromising hero who could force the world to “make sense” by dint of pure will.) Sure, Clyde Fans is light years away from most superhero comics in terms of affect, design, and pacing, but its tragically narrow, emotionally numbed brothers have their own super-lair, their own dark hiding place. This emphasis on entrapped and toxic masculinity, I think, no longer defines alternative comics, which happily have opened out into other themes, identities, and communities. But it sure defines the screwed-up twenty-first-century superhero.

Part of me finds this connection interesting. Part of me finds it depressing. Comics have such graphic potential for psychodrama — for exteriorizing interior states — it’s no wonder that autography is now a dominant comics mode. But, as a reader, I am perhaps less attuned to these lonely, isolated male subjects than I was twenty-two years ago when Clyde Fans began. I recall giving conference papers about nostalgia in comics, about It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken in particular (this was years ago, back in 2001-2002), but that sort of queasy, critical nostalgia has become such a familiar patch of turf, and is so central to the work of well-studied artists like Seth and Ware, that I find myself looking for a way out. Of course, there is no way out of the microcosm of Clyde Fans, short of sheer ornery readerly refusal.

I remain fascinated, though, by the book’s depictions of aloneness. As someone who does a lot of composing and “teaching prep” by literally talking to himself, and whose life alternates between public-facing work and monastic withdrawal, Part One of Clyde Fans rings a discomfiting bell. It’s essentially one man’s obsessive monologue: Abe’s opening soliloquy, as Daniel puts it — or perhaps, as Martha says, his ritual. When Seth started doing this back in 1997 — and that opening ritual took three issues of Palookaville, that is, sixty-plus pages, or more than a year’s worth of cartooning — I could only admire his chutzpah. I figured, well, if you’re going to break the old injunction to show, don’t tell, you might as well do it as willfully and persistently as possible. That was Abe’s ritual: all telling, no show, a slow, puttering, lonesome routine, rendered with unerring patience. Seth’s temerity impressed me; even in the little domestic worlds of autographics and alternative comics, I hadn’t seen such controlled pacing, such deliberate narrative torpor. Yet, of course, there is a hell of a lot of showing going on during that prolonged telling: the microcosm of the Clyde building is imagined and drawn with a precision that bespeaks both ascetic discipline and sensual indulgence. Envisioned to the minutest detail, it becomes a habitable space: as Martha notes, an elaborate fictional world whose mise-en-scène is constructed with the same rigor and consistency as Seth’s Dominion diorama. Formalist that I am, I thrill to the aesthetic challenge posed by Seth’s obstinate narrowing of focus. Where I’ve become skeptical is the idea that this asceticism constitutes a metaphysical vision. Maybe it’s a trap?

There are moments when Clyde Fans hints at a world beyond the Matchcard brothers’ airless retreat. There’s the racist minstrel doll, mentioned by Candida, an ugly marker of history. There’s the scene of striking factory workers, from whom boss Abe is entirely alienated: a sign of how Clyde Fans, the business, moves people and things in a larger world. And there’s the hint of an untold story in Simon’s undisclosed relationship to Emily, a woman with whom he corresponds about the novelty postcards and in particular the work of artist Silas W. Wilfred — in fact Emily is Wilfred’s daughter. This detail recalls It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken, in which Seth’s quest to understand the late artist Kalo culminates in conversations with Kalo’s surviving mother and daughter. As Candida notes, Simon’s correspondence around the postcards represents a sort of connection, however mediated or tentative, with the world outside. But his relationship to Emily never blossoms into a story; she is mentioned only a few times, and we learn fairly late in the book that Simon willfully cut off their correspondence—so whatever the two may have shared remains an unrealized, unexplored possibility (did Seth mean to explore it at some point?). It’s as if Seth thought to include a plot point reminiscent of It’s a Good Life, but then thought better of it (in this way, perhaps, Clyde Fans replies to its predecessor). I have wonder about the sheer volume of potential narrative material Seth must have considered but ultimately rejected, or left purely implicit; throughout Clyde Fans, there’s a sense of impinging “other” stories, barely glimpsed at the edge of our awareness. What remains after Seth’s paring-down is a solitary and cryptic inner world, closed fast.

Heer: Completely agree with Charles that the exploration of interiority and psychological damage is central to Clyde Fans. And this might explain why I, for one, was never expecting it to be an “epic” despite its considerable heft. An epic, after all, is a public art form (the earliest epics being recited by bards like Homer, who served as a kind of communal entertainment). Clyde Fans even in its first chapter had an anti-epic ambience in being private, furtive, cloistered, inward-turned. I was recently reading I was recently reading Samuel Beckett's essay on Proust, written around 1930 or so, and in it Beckett evokes Proust's ability to conjure up "the essence of our selves, the best of our selves... the best because accumulated shyly and painfully under the nose of our vulgarity." I'm not sure what Beckett meant by that but it reminded me of the effect Clyde Fans had on me, particularly the Simon chapters, which go deeper into the mind of an introvert in a way that does call to mind Beckett himself (in his great trilogy) or other modernists like Virginia Woolf.

One other literary analogy might be helpful in terms of getting a sense of what Seth is up to. The Homeric epic has been the standard model for the long poem, but starting in the 19th century there emerged a new way to write a long poem: the life poem where disparate material is held together by a poet creating an open-ended self-anthology bringing together his or her obsessions: examples of the life poem would include Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Ezra Pound’s Cantos, Louis Zukofsky’s “A”, or Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ Drafts.

One other literary analogy might be helpful in terms of getting a sense of what Seth is up to. The Homeric epic has been the standard model for the long poem, but starting in the 19th century there emerged a new way to write a long poem: the life poem where disparate material is held together by a poet creating an open-ended self-anthology bringing together his or her obsessions: examples of the life poem would include Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Ezra Pound’s Cantos, Louis Zukofsky’s “A”, or Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ Drafts.

What I want to suggest is that Clyde Fans can be read not just as a “novel” but rather as a “life-poem.” In other words, the novelistic parts of the book (the plot of the two brothers) is only a device to hold disparate material together but the material itself (and the shifting styles that material is presented in) is of interest because of how it is shaped by the cartoonist/poet: nostalgia, old men, book design, the hold of the ephemeral, Southern Ontario landscapes, nurturing mothers, distant fathers. All of these show up in other Seth projects, but Clyde Fans is the one project that brings them all together. The value of the book, then is, as an anthology of all things Sethian: Seth’s life-poem.

Smart: On the notion of “life poem”: One of the (many) questions that Seth asks his readers in Clyde Fans is “What constitutes proof of a life lived?” A job, a title, a successful life, a family? In both brothers’ worlds there is a common vacuum at their centers. Neither has made much of his destiny beyond a litany of failures. If anything, Clyde Fans is a tragedy—a forlorn tale of two unimpressive people on whom fate appears to have played a malicious trick, leaving them ruined and alone. As Seth describes his characters pictorially there is an odd symmetry in the apparent paradox of their self definitions. Although they appear to be opposite sides of the coin, I can’t shake the thought that they are, in fact, Gemini twins representing eternally dueling aspects of the same soul, cartoon yin-yang complements rattling around in a busted-up building, itself a metaphor of the human heart. This sense is described in a letter by Robin Koustabaris, from Vancouver, published in Palookaville at the end of Part One. (By the way: one thing I miss in the D&Q volume is the “conversation” you get in the original PV issues between readers and author in the “Letters” dept.) Robin writes:

When I sit down and read PV, usually after a few minutes reality drains away and I am sucked into the quiet, contemplative rhythms of the drawings, panel after silent panel, and I can almost hear the drawing thinking. It is the reading experience that is closest to a walk in the woods that I have found. You somehow manage to draw history into each form, and even when they depict something modern-style they still carry the weight of the past, as if the shapes contain all the manifestations of themselves that came before them. … It’s in time, yet somehow out of time.

Robin summarizes for me as well a direction that Seth takes in this story. His purpose is to compress past and present to show how decisions made in years gone by have an impact on the present, and how revisiting the past presents temptations to editorialize or even romanticize a reliable sequence of events and the motivations for actions. As we follow Abe’s story as he meanders around, we feel a palpable heartbreaking anxiety as we quickly come to terms with the fact that Abe’s self-justification is just so much hot air blown from the mouth of a self-deluded narrator.

Seth found his voice and mode in the Clyde Fans drawings and story. His crisply delineated panels are sure and clear, as is the fictional world he depicts precisely in the circumscribed building’s interior. “Nothing’s keeping me here,” Abe brags of his so-called home and office. “I could leave anytime I wanted. Unlike Simon, I never saw this place as a cage.” But he never did leave and while it may not be his “cage,” the interior has an oppressive Kafkaesque weirdness. This is made all the stranger by the authorial point of view—the interior monologue places the reader inside Abe’s head where we get front-row access to a small, self-important view of things pronounced with the authority of a potentate. The question remains, though: Is Abe speaking directly to the reader, or merely justifying to himself all the misguided decisions he has made over his life and business career? Is he seeking proof of a life well lived, or just proving he lived? A life poem on the consequences of hubris.

Marrone: Thinking in terms of a “life-poem” foregrounds the way that Seth simultaneously embraces and undercuts the confessional tendencies in his work (not just in Clyde Fans but in books like It’s a Good Life and George Sprott as well). For me, what leaves the greatest impression in Clyde Fans is Seth’s remarkable excavation of Simon’s inner life.

To put it polemically: Simon Matchcard is one of the great characters of contemporary comics, rivaled only by Lynda Barry’s Marlys and the ensemble casts drawn by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. Of course, it’s very difficult to compare such different works. Even though Clyde Fans was published over two decades, it does not have the open-ended quality of a serial comic, or of the extended Hernandez Brothers Universe. As everyone has been pointing out, Clyde Fans feels centripetal and self-contained, despite its length and breadth.

Do open-ended serial comics lend themselves to characterization in a way that stand-alone comics stories do not (even if those stand-alone stories were serialized)? As a complete work of visual storytelling, Jimmy Corrigan may be regarded as a masterful achievement – but is Jimmy Corrigan a great character? (These are not intended as rhetorical questions.)

Circling back to something Candida said: I do feel affinity and even affection for Simon. I sometimes wonder what it says about Clyde Fans that, unlike many comparable works of fiction, it actually holds my interest. Lydia Davis has a story, “How I Read as Quickly as Possible through My Back Issues of the TLS”, in which she lists the things she does and does not want to read about. (“Not interested in: the creation of the Statue of Liberty//Interested in: beer.”) When I look through the Book Review, I am regularly not interested in contemporary English-language novels, especially those that span decades and revolve around a family: in other words, books like Clyde Fans. The obvious difference is the medium, and Seth’s cartooning certainly accounts for part of the appeal of his stories, but I don’t think I would find Jonathan Franzen’s novels more interesting if they were picture novels.

In terms of form, what stands out about Clyde Fans, particularly Part Five, is the manner in which the words anchor the images and set the pace. I agree with Seth’s suggestion that comics are akin to poetry in their compression, but the actual language in his work is not really poetic, except maybe in a colloquial sense. Even in the final sequences of Clyde Fans, which are elegiac, contemplative, delicately cadenced – qualities we might vaguely associate with poetry – the language has a prose rhythm. Or, at any rate, the language has what I would characterize as a prose rhythm if it appeared without images. Here again we come up against the limits of comparison.

And yet the comparison to Munro is very apt! You’re right, Candida, that Seth has said he’s a fan – in fact, he even expressed specific admiration for what you call “a distanced narrative gaze” in Munro’s work. To echo your comments, there’s a similar narrative texture, a certain measured quality, that distinguishes Clyde Fans.

Postema: It is quite striking how rich this work is in literary references. Others have mentioned plays, novels, poems, comics, and I have another novel to add: there is some of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man in Simon’s morning rituals in the 1966 section (pages 185-6 and 236-7), where is takes him a full page to go from being a body feeling its various sensations to recognizing himself as an individual. Isherwood used this technique to show how reluctant his protagonist George is to still be alive after the death of his long-time partner, having to consciously come into being in the morning. In Simon Matchcard, it may be indicative of the somewhat tenuous grasp on reality he has even on the best of days.

In the 2004 edition of Clyde Fans, Book One, Seth called it a “Picture Novella in Two Books”. The new, complete book has become a Picture Novel, and indeed, with its heft, scope, and interiority, it is a novelistic work. For all that it is a pleasure, and perhaps a bit of a relief, to have the complete version in hand now, I am a little sad that it is only available in the full edition, including Book One and everything else. My old copy of Book One will always remain incomplete--an Abe without his Simon, or Simon without his Abe.

Which makes me wonder what happened to Simon. In the fragmented structure of the work, the last time we see him chronologically is in 1975, when he is living by himself in the Clyde Building, bitter and drinking too much, angry at Abe about their mother’s funeral amongst other old sores. This is part of the long section from Abe’s point of view that includes the closure of the Borealis Business Machines factory, and his last ill-conceived trip to Dominion to reconcile with Alice. Clyde Fans is in decline. As Abe is driving back to Toronto, the interior monologue in the captions reads: “It’s all an illusion out here/ I needed to get back home./ Home… the Clyde Building.../ Its walls and its stairways… Its corners and hallways… Its doors… Its rooms/ The only place where things are solid, tangible...real./ I should’ve known. All these years...its’ been there waiting for me./ That’s where my future lies.../Behind those walls.” We know that Abe is still living behind those walls in 1997, where the book starts. So what happened in the twenty-two years in between? Perhaps this is one of the “other stories... barely glimpsed” that Charles mentions. I imagine Abe and Simon living together for some of those twenty years, Abe caring for his brother the way Simon took care of their mother. Maybe this is in part what has led to a mellowed Abe in 1997, since much of the acrimony he felt earlier in life seems to have dissipated. One could attribute the mellowing to age alone, but I like to think of it as the result of the brothers living together for a time. Clyde Fans never shows them close to each other, barely shows them in the same room, though their pictures always hang side by side. But this missing time may suggest that for a while they were brothers who were able to be there for one another.

Hatfield: Perhaps I’m being unfair to Clyde Fans, from which, after all, we seven have gleaned so much. Re-reading my comments above, I can see myself resisting the book’s pull, as if afraid to yield to what is, after all, a constant part of me: the impulse toward nostalgia, and toward, frankly, the obsessive would-be ordering of my surroundings into detailed arrays of stuff. I get it. I mean, I sort of live it. As I get older, I don’t want to live it, so my critique of Clyde Fans perhaps has a semi-autobiographical dimension, or amounts to arguing with myself. I was deep into Seth’s work at the time of the collected It’s a Good Life, and I’m reluctant to throw myself into it so deeply now. I’m older, and I can sense the way so much of my daily thinking now revolves around past experience. That means I have grown into a distinct outlook, and maybe a kind of personal language, but also that my head is filled with echoes. Against this tendency, I’ve tended to counterpose my determination to stay current -- to keep tabs on what’s happening in comics now and learn to dig things I wouldn’t have read twenty years ago. The time-capsule quality of Clyde Fans has me ambivalently thinking about the alternative comics of the '90s, and how comics since then have sometimes fulfilled, sometimes abandoned, and sometimes gloriously overleapt the promise of the early Palookaville and its kin.

As a meditative visual poem, Clyde Fans reminds me of Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”, in which he famously longed “To see a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour.” Simon’s final grand mind-trip in Clyde Fans seems to grasp after “eternity in an hour,” maybe in a spirit of quiescence, or maybe with dread. But the book’s very miniaturist nature, its intimacy, has inspired us seven to open up a number of different personal worlds. If Simon and Abe’s horizons seem small, well, the book’s yield seems to be pretty damn big after all.

Charles Hatfield, comics scholar, professor, and critic, is a co-founder of the Comics Studies Society and a longtime contributor to The Comics Journal.

Jeet Heer is a contributing editor at the The New Republic, and a former columnist at The Comics Journal.

Martha Kuhlman, Chair of English and Cultural Studies at Bryant University, is currently working on an edited volume titled Comics of the New Europe, to be published next year.

Daniel Marrone is the author of Forging the Past: Seth and the Art of Memory. His work on comics has also appeared in ImageTexT, Canadian Review of Comparative Literature, and The Canadian Alternative: Cartoonists, Comics, and Graphic Novels.

Barbara Postema's first article was on Seth's It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken, in the International Journal of Comic Art. She has gone on to publish many more articles and the book Narrative Structure in Comics. She teaches at Massey University.

Candida Rifkind is Professor in the Department of English at the University of Winnipeg, Canada, where she specializes in graphic narratives, life writing, and Canadian literature and culture.

Director and CEO of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Tom Smart is also the author of Palookaville: Seth and the Art of Graphic Autobiography, published by the Porcupine’s Quill in 2016.