Anne Elizabeth Moore is a writer, journalist, and cultural critic. She’s the author of many books including Unmarketable, Threadbare, and Body Horror. Melissa Mendes is the cartoonist behind Lou, Freddy Stories, and The Weight, an epic family saga that she’s serializing online. The two have been collaborating for many years, but since last year they have been making a series of monthly nonfiction comics for Truthout focused on water, land, and housing in the city of Detroit. These comics are extensively researched and reported, complete with footnotes and citations. At a time when Detroit continues to be in the news, these reports paint a much more complex picture of the city and its residents, their personal stories, the structural impediments to progress, and the history of how they came to be.

The series is going on hiatus this month, though Moore and Mendes are continuing to collaborate and are completing a book together about Detroit, which will include these comics, tentatively titled The Only Interesting City in America.

Alex Dueben: Anne, people might know you for your books or your articles, but you’ve been writing nonfiction comics for years. What interested you in the form and how did you first start writing them?

Anne Elizabeth Moore: I think what’s important to keep in mind is that, since I started in the realm of self-publishing, there was very very little division between comics and text and art when I was learning to be whatever it is I am today. The very first thing I ever published myself, at the age of 11, was a comic. There’s lots of evidence that women’s experiences in the realm comics aren’t validated or acknowledged, but that’s how I started and thousands of internet detractors aren’t going to change that. So I first started writing comics when every dude who writes comics did, in a living room, hunched over a tiny piece of paper with a pencil, while all my friends were playing outside. Like everybody else who got started that early, I thought I invented making my own little books! We don’t get to hear that story with a girl protagonist very often.

What is unusual, it appears, is that I was always drawn to nonfiction and reporting, and self-published almost reflexively. A thing would happen, and I would witness it, and a couple hours later there would be a zine. Or someone would tell me something crazy. I have a bad memory so the immediacy of it became really important, like not just in terms of the work but in terms of my life. Discovering comics journalism was really, like, it just fit. I mean, there wasn’t much of it in the 1990s, but bits and pieces here and there gradually contributed to this sense of what comics, and reporting, could be if they got their shit worked out.

To do it, though, I really felt like I had to go out and do work that was no-question, front-lines journalism. Get my chops. And that becomes addictive. Once you’ve gone on tour with the first public group of transwomen in a developing nation or talked your way out of a kidnapping or lunched with a mass killer, you get on this adrenaline-fueled cycle, chasing the next story. Comics take a long time, too, plus it took a while to figure out how to reintegrate the reporting with the images in a way that reflected the accuracy of my immediate experiences but retained a contextual analysis that’s much easier to do in text. Melissa’s right that approaching these strips as an illustrator isn’t the way to do it. It takes a much more invested, curious approach. The images have to fit the logic of the environment described, not just depict a particular view of what appeared to have happened. People are always surprised to find out Melissa doesn’t live in Detroit. Well, that’s sort of not true. What happens is that people are always congratulating me on my amazing drawing skills, and then I may or may not mention Melissa. Usually I do.

How did the two of you first start collaborating?

How did the two of you first start collaborating?

Melissa Mendes: A few years ago, I was marginally aware of the Ladydrawers and thought it was very cool. I was a little envious of them even, it looked like something I really wanted to be a part of but I wasn't sure how to approach them. Then Anne asked me if I wanted to draw for Threadbare, and I was like, um, yes please. So I started out drawing a few chapters of that, and it soon became clear that we really worked well together. There's something that clicks with us, that's kind of hard to pin down—but I think it could have to do with the fact that I consider myself a writer more than an artist, so I approach Anne's scripts like a writer, rather than just drawing exactly what she's written, like an illustrator might. And we are just similar in a lot of ways, we communicate really well. She's hilarious. So I think when we started the Detroit project there was a level of trust there already and that's made it really easy and fun to work together. Also I love doing my own research, like when I had to look up old pictures of Black Bottom in Detroit for one of the stories. I learn so much and it's fun for me, so that helps.

Moore: We had met years before that, when a friend introduced us in Providence, but I’ll admit it took a while for me to “get” Melissa’s solo thing. It’s sort of deceptive, in a good way—immediately palatable but something often happens that’s rooted in trauma or discomfort. Once I figured out that she’s using cuteness and innocence almost as tricks to pull you into these very, very complex stories I felt like we had something particular in common, something about not being interested in letting the sheen go untarnished, or something. “Wanting to peel back the skin,” might be a better metaphor. We watch a lot of lady detective shows.

One of the things I always flash on happened sometime after Threadbare, during a Ladydrawers series for Bitch Magazine. We had to invent this throwaway character as a way of talking about—I don’t remember what. Gender bias or whatever. Money, probably. I think we were riffing on Pippi Longstocking, or both reading those books at the same time, and we came up with Violet the Pet Detective, a little kid who’s a detective who solves animal-related crimes but everyone respects her so much they treat her like an adult. And she was only in the strip for a couple panels but we worked out this elaborate back story about her and several complete storylines. We talked about doing children’s books or something, and those stories are still vivid in my head. I think for fiction people that doesn’t sound remarkable, but as a journalist I hear a loooootttt of crazy stories from people, true stories, that drive out most of the other stuff. You wouldn’t believe. Having a detective who’s young and smart and happy and well-respected and concerned about animals stick round for awhile is something, when it’s competing against, like, I had to eat a guy once to survive, or my brother is not the pedophile the state says he is.

Mendes: Maybe Violet is like, the embodiment of both of us wrapped up in one little crime-solving package. Also, I would like to hear that story about eating a guy to survive.

What do you two think comics can do that an essay or report couldn’t?

Moore: This is a question I get a lot, since I’ve done both text-only reporting and comics journalism. There’s a particular story in Threadbare I did with Julia Gfrörer called “Let’s Go Shopping,” about fast fashion retail work. I went into a local H&M—it was years ago, now, so that worker’s not there anymore—and started chatting with one of the retail workers. Now, like factory workers, and many many other workers along the entire garment production and display assembly line, retail workers for most fast fashion outlets sign non-disclosure agreements stating that they agree that they have the right to be fired if they share information about their benefits or wages. This is a nutso clause in any contract designed to keep people from sharing information and organizing to improve their lives, and it’s basically a knife wound to the project of basic democracy, since it means that even though a LOT of people work in the garment industry, few people talk about what it’s like and so, for example, reporters usually struggle to write about it because no one will go on record.

But no one knows, or cares, what comics journalism is, so I walked into this H&M and was like, “Yeah we draw this thing and it works like this and I do need a photo for reference but we can hide your identity to protect you and if you want we can draw you in your favorite outfit even if you aren’t wearing it right now, I just need to ask you a few questions that are in complete violation of your NDA are you OK with that?” And she answered everything I asked. Because with comics we were able to protect her, but also depict her in an interesting way, and she was invested in contributing to something she would be excited about. (That Julia drew it was super helpful. She is very very popular with models and fast fashion workers.)

That’s an actual example of information that wouldn’t have been accessible without the form of comics. In “Scenes from the Foreclosure Crisis,” Melissa and I were able to do a very similar thing, depict a nonbinary figure, who still has a very clear personality, history, and set of concerns, in a way that wouldn’t bring them undue attention or frustration. Or violence, to be frank. (Detroit is very conservative, actually, so that’s a concern.) In text-based journalism, you’d have to give some kind of identifying distinction, and almost anything I could think of in this case would put my source in danger.

Also audience, of course: comics journalism is read by a far less newsy crowd. More young people. I hear from a lot of students that this was sort of their gateway drug to text-based journalism. But it takes a long time, so you have to plan it all carefully.

Mendes: Whenever I get this question I always think of Joe Sacco. There's no way his work (Palestine, The Fixer, etc.) could ever be anything other than a comic. He's going into these terrifying places, these war zones, and instead of just taking photos, which can be sort of voyeuristic, he's drawing. There's no question that it's through his lens, that it's his own point of view-- he's making those marks on the paper. There's no way it could be taken as objective, while it's possible to write or photograph or record in such a way that you forget there's a person behind the camera or the keyboard. (I'm sure there are smarter words for what I'm trying to say but I haven't written a college paper in like fourteen years so...) Does that make sense? Sacco is reporting, but it's personal, and you feel that as a reader. You can't escape it, it's more raw somehow. The handmade aspect of cartooning makes it more human, and we are still able to protect identities, like Anne was saying.

For the past year the two of you have been making this series about Land, Water and Housing in greater Detroit. What was the impetus for this project and what was the initial plan?

Moore: Well, in 2016 I won a house in Detroit, and what was sort of incredible about it was that the work I submitted as my writing sample was the comics journalism stuff that later became Threadbare. Often when you submit comics instead of text for a writing award you get laughed out of the room. There were TV crews there when I moved in, and the city councilperson, and a bunch of local interesting people, and they asked what kind of work I was going to do in my new house, like on TV. I maybe didn’t think it through very thoroughly, or I would have developed a plan before I said anything out loud about it, but I basically said, “Of course I am going to do a series on water and housing and land access in Detroit in comics form!” Then I felt like I had to do it.

Probably more significant was that Melissa and I had worked together just enough for me to sense what she might be good at, that this story needed, and that she wouldn’t otherwise have the chance to do, so it was designed from the start to be something she would be involved in. If she’d said she wasn’t into it, it wouldn’t have happened at all. There’s just no way to tell this story without relying on the deep character development work she does, and her concentration in recent years on telling stories about folks living under duress—if you haven’t read The Weight you are basically dead to me—and the way that she builds out a narrative logic visually that may not correspond to the stories we’ve all been told—this takes an intense amount of skill that most folks in comics just do not have.

For me, the great thing about being a totally independent creator is being able to build projects around emerging interests and sudden opportunities, and I personally have the capacity to become fascinated by almost anything. I have that disorder that is the opposite of attention deficit disorder, where I can just sink into any boring old thing and find out crazy stuff about it: attention surplus disorder. Stuff might be catching on fire in the room with me, but if I’m working on a piece I may not even notice.

The title we’re working with for the book, The Only Interesting City in America, I should mention, was sort of inspired by this dude I met at a campfire in a fairly remote Western Finnish village who’d never been outside of the region, much less Finland, and had never heard of Chicago—like the word meant nothing to him. But I’d just moved to Detroit. His English wasn’t very good, but when I told him that he said, “Ah. Only interesting American city.” He’d read like four books about Detroit, in Finnish, and had all these questions for me. That’s amazing, that people are so fascinated by this place, and presents an amazing opportunity to talk about how people can live together under incredible circumstances.

Mendes: Oh my god, I just realized I also have attention surplus disorder and maybe that's why we work so well together.

Moore: Ha ha, that makes sense. Melissa and I also the same genetic disorder. We have never talked about whether or not we are both RH negative but I wouldn’t be surprised. Did you know RH negative people can’t be cloned? I read that on a website.

How do the two of you make a comic? What's the process of making one?

How do the two of you make a comic? What's the process of making one?

Mendes: Anne does all the initial research/interviewing. Sometimes we text back and forth about what the subject should be, or what direction we should move in. I mean we are always texting but sometimes it's just pictures of our cats. Which is also important.

Moore: It is, actually, because it also kind of gives us an in with our subjects. Like Melissa Mays, who was one of the first people to identify what became known as the Flint water crisis, which is ongoing, and whose story is depicted in the Lifetime movie, Flint, she’d told her story one gazillion times. So when I introduced the idea of the comics series to her, and started talking about how Melissa and I work together, I mentioned cats, and she started in right away with the story of her cat, who got sick from the water before any of the humans did, and that was what got the whole thing going in her household. It gave us this whole different perspective on her story, The Cat Angle, which let her open up as an interviewee and made the story a lot more personal for all of us.

Mendes: Cats are the thing that will unite us all. So, she interviews our subjects, visits places, takes pictures, does the research and then she writes a script. Honestly this part is kind of magic to me. She's a journalist, which is something I've always admired and kind of wanted to be. I had dabbled in non-fiction comics before we started working together, but it always scared me a little. So getting to work with her is kind of a dream. I get to be a journalist without the scary part of interacting with people and going places. I can just sit in my studio and draw. But maybe this book is making me a little braver. I'm going to Detroit for 2 weeks this summer and I'm starting to get excited about meeting all these people and places I have drawn.

The other thing that's awesome about working with Anne is the level of trust we've reached. In her scripts she’ll write ideas sometimes for what the scenes should depict, but the longer we've worked together, she more she leaves those blank, and just lets me figure out what to draw. Working with her is great because she really lets me just go wild. Sometimes she'll have feedback on what I've chosen to draw but rarely if ever has comments on my style or anything, which is great. It's not like working with an editor or someone who has no clue about comics who will tell you to redraw a hand 500 times. It's a real collaboration. Honestly I'm probably pretty spoiled by her! She's also just an incredible writer. Have you read Body Horror? I mean, come on. Her writing is so visual and visceral that I think it pairs naturally with comics.

So basically our collaboration goes like this: I get her script, and I read it through, thumbnail it, and get her approval on those. Then I pencil the whole thing, and send those to her for feedback. Finally I ink the text, then the images, and add the grays. Then I scan and color. Because we publish online at Truthout there's a common format to all of them, which is helpful when laying out stuff. I keep it simple and don't go too crazy that way.

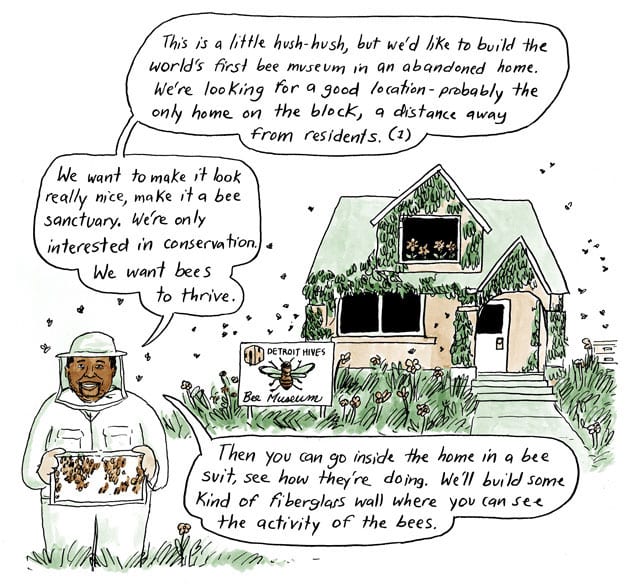

Moore: [laughs] Approval. I mean, maybe in earlier days I felt like I had to have some kind of control over how this would all come together, but with this series it’s more like, Melissa and I are kind of inventing this form. I mean, people do comics journalism, but I don’t know anybody who’s been doing a collaborative investigative comics journalism series—I’ve been doing it for seven years now, and by the way thanks, Truthout!—this consistently, for this long. Mostly once we’ve agreed on a storyline for the next strip, I do the part that needs to be done that I do—interview the people, do the research, run some numbers, make some calls, and take pictures of stuff that’s unique or unusual or that I think might work best a certain way. There are strips that feel lighter, or that we can afford to joke about because the potential for human death is a little bit removed, like in “Blight!” or “Sanctuary,” which is about honeybees, but also these two great beekeepers. But by now there’s a way that that I write these scripts, so I do that, and then my job is kind of done until it’s time to check the spelling. Sometimes I’ll get a text from Melissa that’s like, “So these panels…” and it’s always like, “We both know you sent me these panels because you think something’s off about them but OK, I’ll be the bad guy.”

Also Melissa says she doesn’t like to go places or do scary things but we went to Fairfield, Iowa for a weekend to check out the totally bizarre Maharishi University of Management, which is the seat of the Transcendental Meditation movement in the US, although it’s also called a cult and is definitely a massive, if failing, business. And we would get to, like, a place where non-meditators weren’t supposed to go, or women weren’t allowed, and Melissa was always like, “Let’s go see!”

Mendes: That's just because I'm nosy!

Melissa, this is different from the work a lot of people know you from like Lou and The Weight. Does making nonfiction comics require you to work differently than how you have been?

Mendes: I love working on these comics with Anne because it gives me a mental and emotional break from my fictional work. It's much more straightforward and streamlined. There are rules and grids and structure already set. Less freedom is sometimes a good thing!

The very first comic I drew for Threadbare, I think the first panel was just some shipping containers. And I was like, holy crap, this is great, I love drawing from reference! I don't have to worry about my character looking right, or about the story. When I am just lettering one of our comics, I can sort of zone out, but my pen is still moving. So it's like, hardcore training for my drawing hand.

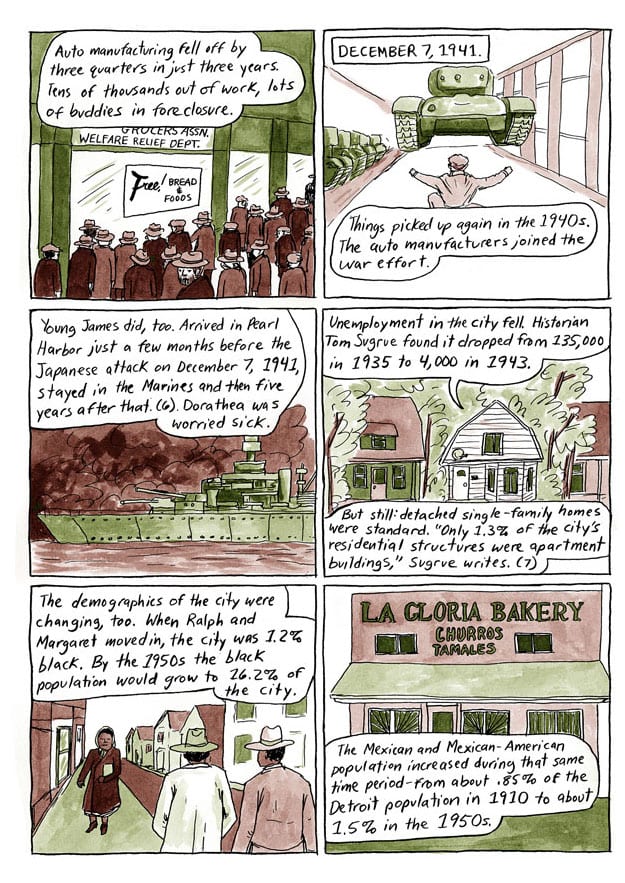

The Weight, for people who don't know, is a comic I'm currently working on that's inspired by my late grandfather's life. He wrote a short memoir for a writing class before he died that has lots of details that I didn't know about his childhood in rural upstate New York. He grew up in poverty with an abusive, alcoholic father, a theme that I address a lot in The Weight. It's not an easy story to tell. But it's the biggest project I've ever done and it feels very important. I've been working on it for a couple years now, and I have about 200 pages done, and I probably have about 200 more to go. I'm inspired by family sagas like East of Eden and The Thornbirds, and my story will span the entirety of the main character's life. At least, that's the plan.

So yeah, The Weight is a heavy project for me. It takes all of my brain and heart to make, and I'm so deeply invested in it. That's what my fictional work is to me—it’s emotion, it's my heart, and working like that all day every day can be exhausting. It’s definitely true that much of the subject matter that Anne and I deal with can also be emotionally devastating. A lot of times I have to step back a little and just draw and not think too much. I have to be a little bit removed, which is maybe a luxury I have because I'm drawing and not doing the reporting like Anne is. So it does give me a little reprieve. I can watch Real Housewives while I draw our comics – but sometimes I realize how gross it is to be watching Lisa Vanderpump buying jewelry for her dogs while I draw stories of families losing their homes in Detroit and I have to turn it off. I can't watch TV while I draw The Weight. I can listen to podcasts when I ink but I need silence for penciling and writing.

So yeah, The Weight is a heavy project for me. It takes all of my brain and heart to make, and I'm so deeply invested in it. That's what my fictional work is to me—it’s emotion, it's my heart, and working like that all day every day can be exhausting. It’s definitely true that much of the subject matter that Anne and I deal with can also be emotionally devastating. A lot of times I have to step back a little and just draw and not think too much. I have to be a little bit removed, which is maybe a luxury I have because I'm drawing and not doing the reporting like Anne is. So it does give me a little reprieve. I can watch Real Housewives while I draw our comics – but sometimes I realize how gross it is to be watching Lisa Vanderpump buying jewelry for her dogs while I draw stories of families losing their homes in Detroit and I have to turn it off. I can't watch TV while I draw The Weight. I can listen to podcasts when I ink but I need silence for penciling and writing.

Our work together has also made me a thousand percent better at cartooning. I could not have done The Weight without experimenting with inkwash in our first Truthout comics. I've gotten so much more confident in my own skills since we started working together. I think now I might be brave enough to do my own non-fiction work. Maybe.

Moore: Did you just break up with me? Just kidding. Your non-fiction work is nuts, people are going to love it. I hope you still let me hang out with you at your Cartoonist Mansion.

Mendes: Only if you bring your cats.

Anne, you’ve been living in Detroit for a while now. I’m curious what has surprised you about the city and what do you hope people take aware from the series and understand?

Moore: I came here pretty open, which is the best way of going anywhere new and actually engaging with people. I mean, I’d read all this stuff about Detroit and been here a few times and heard stories, but none of that stuff ever really amounts to how things are in a place—which I wrote about recently a bit for The Baffler, the vast difference between what we think we know about Detroit, specifically the 1967 uprisings, and what is true about it. Of course my actual situation is really unique within this already intense city: I was given a house in a part of town originally built up a hundred years ago to house immigrants coming to help Hitler fave Henry Ford move from hand cranks to electric starters in the Model T’s, and now largely resettled by Bengali immigrants who honor the white supremacist patriarch by refusing to drive domestically produced vehicles. So either every single thing surprises me about the city, or nothing does anymore.

I gave a talk at an art museum the other night, and it was my first chance to show this stuff off in Detroit. People don’t spend a ton of time reading here—literacy rates are really low, and there’s not much in the way of local media at all, much less quality local media, so to be honest it’s not like I blame anyone for not reading—so giving talks like this ends up being one of few ways you might actually be able to share ideas publicly. And with all the infrastructural problems the strip presents, and all the ingenious means of navigating them we cover that allows people to survive, it can feel a little oppressive, when seen as a whole. It often seems that this city just straight-up hates the people who live here. They’re written off, put in danger, pushed out. Their water gets shut off, they’re foreclosed on, their houses are torn down, they aren’t given permits to run businesses or buy land to farm on, and then the city promises great chunks of real estate to places like Amazon because, why, it clearly loves white rich dudes?: it’s preposterous. Every day, it would be laughable if it weren’t making people sick, or displacing them, or killing them. Those water shut offs a few years back everyone was talking about? They still happen, if you haven’t read the series yet, and they have a lingering public health effect that, for example, is currently fostering a Hepatitis A outbreak in the city. Folks like me, with already compromised immune systems? That can kill us, easily. Like I am in more danger here every day than I ever was in Cambodia when the government was having garment workers shot.

The difference is that here, although it’s not terribly functional, we do still have a democracy in place. Making it clear in the series that there are individuals elected to public office that are allowing for or perpetrating many of these most damaging acts, or failing to develop any protective measures for the residents, is one big point of what we’re doing with the series. It often feels really helpless here, and folks get really angry with each other instead of angry at the systems that are causing their lives—our lives, because this is part of the point, I’m embedded in this, too—to feel out of control. But actually, what the series tries to do is map those ley lines so folks can see how much control they actually have.

What is the next comic? How many more do you have planned for the series?

Moore: The final strip in the Truthout series is in the works now. We’re finishing up the section that looks at land by talking about how the city of Detroit came to exist in the shape that it’s in, how two whole other cities sit inside its borders, how the suburbs emerged and how and why and when. There’s a wall in the northwest side of the city that was intended to keep black folks out of white neighborhoods. A wall, for fuck’s sake. This city was shaped by fear and greed and rich people, in a mappable way. And it connects that to some of the contemporary land-purchasing practices—who is allowed to buy land and what they are allowed to do with it—currently at play in my own intense little neighborhood.

Then the series goes on indefinite hiatus until Melissa and I finish the book. We’ve been working with some folks at Power House Productions on an NEA-funded project to do three more strips about this neighborhood in particular, that will start to pull some of my neighbors into the practice of comics journalism. Melissa will come out in July, and we’ll get to poke around and do some of those interviews together, meet some of the folks she hasn’t met before, hang out with cats.

Mendes: Yeah, I'm super excited to go out there this summer and meet people and actually see the places I've been drawing!

I'm working on The Weight always. When we have breaks between deadlines I try to get as much done as possible. I post pages online on my website and on a mailing list. I try to post two a week, but ideally I'm drawing a page a day. When we finish our book I'll probably hunker down and just try to get it all done. I'm also drawing four panel comics about Freddy, a character from my book Freddy Stories. I've basically drawn her off and on since college, in short stories and daily comics. But you can only see them if you become a patron on my Patreon. Because I gotta pay the bills.

Moore: What I’m working on now is a critical overview of Julie Doucet’s work for Uncivilized. It’s so much fun, but oh my god is it crazy to be thinking about her career in the wake of the Weinstein revelations. Every day I sit down to write, I think to myself, “Is this real that I am the person who gets to think through this right now?”