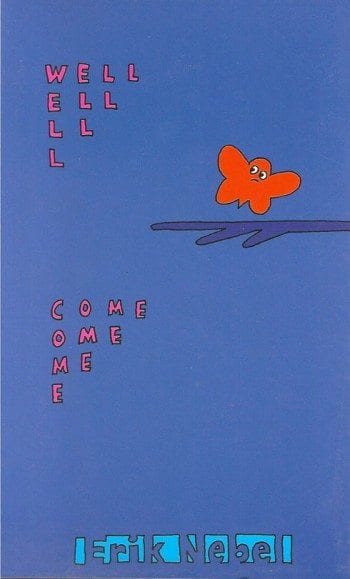

For a faktish yokle who says he approaches comics as "a word guy, not a picture guy," Erik Nebel’s Well Come (Yeti Press, 2014) presents a challenge. Pictures, it has plenty (282); words, not so much (0). You ever feel you came to the smorgasbord without a mouth?

For a faktish yokle who says he approaches comics as "a word guy, not a picture guy," Erik Nebel’s Well Come (Yeti Press, 2014) presents a challenge. Pictures, it has plenty (282); words, not so much (0). You ever feel you came to the smorgasbord without a mouth?

Nebel, who lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife and two children, has worked in the theater and film, and now teaches elementary school. The pictures he presents lie in three panels per page, one above another, all of equal size, wider than they are tall. They are glossy, jolly, glowing colors, applied flat and smooth. The pallet is heavy on blue, yellow, red, plenty orange, purple, some black, a little white. Brown enters late and green, almost an afterthought, later still. There is no cross-hatching or shading and little perspective. The objects portrayed have flat simplicity and charm like grade school cut- outs from poster paper. This paper, though, is of better quality.

Words or not, Well Come is bound like a book, so the impulse it to treat it as one, not as, say, a pack of trading cards. So as the eye follows the panels down one page, before crossing to the top of the next, scanning the images en route, the mind, stimulated by the changes noted within these panels, imposes a narrative. "Characters" are identified; "plot" is ascertained; "actions" are linked, "consequences" experienced; and emotions – true emotions – felt. Then, after a varying number of pages, as short as one, as long as a dozen, shifts in the figures or their coloration lead to the conclusion that one story has ended and another has begun.

These narratives seem similar. The different meet, interact, and are transformed, partially or entirely. They may remain together, or separate and move on. There is something satisfyingly jazz-like in Nebel’s effort. (Cartoonists doodle; musicians noodle. Coincidence? I don’t think so.) He seems to improvise his way upon shape and with color, as musicians do with chords and tone. Then when he has exhausted a phrase, he moves on.

Well Come instructs with a light hand. It is not just that there are no words. D. W. Griffiths did not need them to be didactic as all get out. It is that the "action" is less than on the walls of the Chauvet cave. But the book seems to me to put forth questions whose answers are rewarding to pursue. It suggests we ask ourselves what makes a "story" and when (or how) a painting (or drawing) may differ from one. And it casts light upon the ways in which a viewer-reader’s mind interacts with an artist’s work to "complete" a created project. The final effect is oddly satisfying and refreshingly stimulating.

But I worried I might be missing several boats. So I asked Nebel some questions. Here are two, and his answers.

But I worried I might be missing several boats. So I asked Nebel some questions. Here are two, and his answers.

LEVIN: Why did you "write" a book with no words?

NEBEL: I am a Speech-Language Pathologist, and I work with students who are non-verbal and students with Autism and students who are Emotionally Disturbed. Part of my therapy with these students involves drawing pictures as a way to communicate, instead of using words. I remember one day looking at some of my drawings and thinking, "Hey, wait a minute. This would make an amazing comic." So I drew comics based on those drawings, and some of those comics ended up in (this) book."

LEVIN: Do you have a "message" you wish readers to take away from WELL COME and, if so, what do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of.delivering it non-verbally?

NEBEL: What I hope readers take away from WELL COME is a feeling of Wow!!! I want readers to experience a range of emotions like happiness, sadness, anxiety, surprise, confusion, discovery, and delight, mixed together in a combination that is unique. I’m not sure what the strengths and weaknesses are of delivering the message non-verbally, but I haven’t felt hampered by not using words in WELL COME.

II

R.L. Crabb, an ex-newspaperman and rock band lyricist, the author of about 20 comix, and a contributor to a dozen others, is a word guy. Scablands, his latest, is available from the author (P.O. Box 313, Nevada City, CA 95959).

R.L. Crabb, an ex-newspaperman and rock band lyricist, the author of about 20 comix, and a contributor to a dozen others, is a word guy. Scablands, his latest, is available from the author (P.O. Box 313, Nevada City, CA 95959).

Crabb is writing in the present, but a spat of recent deaths has led him "to gather up the fragments of my life." Most tellingly, his parents, who had been secretive about their life, had passed, leaving an unfillable hole in his and motivating his wish "to lea ve something of myself behind." The result is an assemblage of stories, most of which occur in eastern Washington state 20 years ago but enlivened by rollicking recollections of the Bay Area, between 1984 and 1990, and Atlanta in 1973. Star-quality pizzaz is achieved by references to gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson, porn film moguls Jim and Artie Mitchell (none of whom actually appear), and that "shadowy figure of myth and legend," the cartoonist Dan O’Neill, who does. Spiritual depth is provided through dippings into, extractions from, and reflections upon Drummers and Dreamers, the tale of Smowhala, a 19th century prophet among the Wanapuni Indians.

Crab Man, as he apparently known to intimates, is an autobiographer of the humorous, down-and-dirty school. Broke, under an ex-wife’s restraining order, the target of two judges he’d antagonized, and abandoned by a girlfriend who’d "run off with an Irishman," he accepts a biker buddy’s offer to lodge in a trailer on his property and assist him in repossessing cars. Fueled by beer, caffeine, Rumple Minze, and greasy diner food, and pummeled by memories of smack, crack, and a year spent in traction, Crabb snatches vans, Corvettes and Mavericks from angry owners whose dreams had been "left in another life." This hunt plays out in "flyspeck" towns, within a landscape dominated by a nuclear waste storage facility, whose holdings are said to include the remains of hundreds of experimental test beagles and 17.5 tons of their radioactive excrement. The area is known, resonantly, as "The Corridor of Death" because its ecosystem had once been extinguished by melting glaciers of the Ice Age’s melting glaciers, leading Crabb to muse that nature again seemed ready for "cleaning out its inventory."

Crabb’s pictures serve primarily as underlining strokes for what he has written. While his book could exist without them, his illustrations, add a humor and provide a dimension words alone would not convey. To see Crabb’s and his buddy Duane’s backs – and their streams – as they share a roadside piss is more evocative than if this act was simply described. The naughtiness of the depicted piss is just plain funnier than the written word. Having Crabb’s representation before us throughout his tale, balding, eye-glassed, gaunt, frantically laboring through his exploits, keeps the precariousness of his situation before us in a way that a written description could not. On the comic page, it is just there. In an entirely textual work, he would have to be annoyingly re-describing himself over and over to achieve the same effect.) And having the radioactively poisoned pooches represented by Snoopy brilliantly drives home the horror of their slaughter in a way that simply reporting the death of "beagles" would not.

Crabb’s pictures serve primarily as underlining strokes for what he has written. While his book could exist without them, his illustrations, add a humor and provide a dimension words alone would not convey. To see Crabb’s and his buddy Duane’s backs – and their streams – as they share a roadside piss is more evocative than if this act was simply described. The naughtiness of the depicted piss is just plain funnier than the written word. Having Crabb’s representation before us throughout his tale, balding, eye-glassed, gaunt, frantically laboring through his exploits, keeps the precariousness of his situation before us in a way that a written description could not. On the comic page, it is just there. In an entirely textual work, he would have to be annoyingly re-describing himself over and over to achieve the same effect.) And having the radioactively poisoned pooches represented by Snoopy brilliantly drives home the horror of their slaughter in a way that simply reporting the death of "beagles" would not.

Crabb’s belief in the written word is made manifest by his take on Showhala. Showhala, had relied on his people’s oral tradition to pass on his memories and lessons. But as his tribesmen dwindled and disbursed, these stories would have disappeared had his last surviving relative not collaborated with a journalist to preserve them in book form. Crabb’s review of his own life through this filter finds justification for his own, often erratic, troubled, seemingly hapless, keeping-on keepings-on. Some stories, he instructs, "you try to live through... some you try to live down... and some you just stumble across"; but, regardless, by embracing and trying to make sense of them, you can give value to your life. "Life comes and goes but stories are immortal," he concludes, "but stories are immortal. They tie the past to the future."

He leaves us – and himself – unable to "wait to see what happens next."

So I asked Crabb why he went with pictures, not words alone.

"I wish I could give you some high brow reason...," he told me, "but the simple truth is I just like cartooning. The first five issues of (my comic) Adventures on the Fringe were done as illustrated prose rather than straight comics... because there was just too much story to tell... Comics fans did not receive it with great enthusiasm. Scablands may well be my last foray into graphic novels. I suffer from an arthritic condition that makes sitting for long periods painful....As a result my feet have gone numb.... But then, I guess artists have to suffer for our craft. At least, I didn’t cut off an ear."