It was 1987 when the nascent VIZ Communications, bolstered by the financial backing of manga publisher Shogakukan, began releasing its first English translations of Japanese comics. They were made available to North Americans as comic books, published under the auspices of Eclipse Comics, as that was deemed the most efficient means of getting manga into sympathetic hands. Similarly, the series selected for publication seemed targeted to best flatter the interest of comic book readers: the mercenary action of Kaoru Shintani's Area 88; the feudal swordsmanship of Sanpei Shirato's The Legend of Kamui (which was immediately pressed into competition with First Comics' contemporaneous translation of the Kazuo Koike/Gōseki Kojima classic Lone Wolf and Cub); and a superheroesque teen psychic drama titled Mai, the Psychic Girl. The scenario was by Kazuya Kudō, a Golgo 13 scriptwriter who'd also collaborate with a young Naoki Urasawa on Pineapple Army, a comparative obscurity from his glittering catalog of success.

The artist was Ryōichi Ikegami.

Mai is not extremely well-known today, but it was fairly popular at the time of its translation - probably more so than during its undistinguished Japanese serialization. Tim Burton was even supposed to make a movie. Much attention from readers fell on Ikegami's art, which was genuinely unlike anything else in comics: extremely 'realistic' and anatomically precise, yet also fascinatingly restrained, so that character bodies are frequently comprised of simple thick outlines, with small, tactical strokes used to suggest an unnerving degree of verisimilitude. To the acclimated, it was all quite manga, but it also suggested a heaviness presumed at that time to be exclusive to American and European comics.

The very next year, VIZ -- having broken away from Eclipse to publish comics themselves -- elected to close the gap by releasing another Ikegami project, this one written by Koike of the aforementioned Lone Wolf.

This was Crying Freeman, parts of which are *still* in print today.

Undoubtedly, it helped that Ikegami is an avowed admirer of American comic book artists, particularly Neal Adams. Think about it - a 'Japanese Neal Adams' on the roster could only firm up the tenuous grip Japanese comics held on North America, and indeed it was a steady stream of Ikegami work that flowed into English throughout the 1990s, including the high-profile political/crime thriller Sanctuary, written by Shō Fumimura, who (under the name "Buronson") co-created the quintessential '80s boys' violence comic Fist of the North Star, and continues to collaborate with Ikegami to this day... not that you'd know it around here.

Manga, you see, had changed. Or, rather - what "manga" was understood to be in North America had shifted with the millennium. The American publisher Tokyopop had become a powerful force in comics distribution to big box bookstores, rather than comic book stores, and efficiently marketed manga to young readers on the basis of its differences from North American comics: the bookshelf-ready collected format; the small size and low price; the sprightly cartooning and teen-friendly subject matter; the tremendous amount of work intended specifically for girls and young women. This was never Ikegami's territory, not even in Japan. Barring reprints of old favorites, there hasn't been an Ikegami project legitimately translated to English in twelve years.

And perhaps it's a result of this neglect that remarkably little has been written about Ikegami's origins, and the slow development of his signature style. When the Center for Book Arts in NYC ran its Garo Manga: The First Decade, 1964-1973 exhibition back in '10, some were surprised to learn that Ikegami was among the early contributors to that revered, politicized, alternative magazine. Others are unaware that Ikegami drew hundreds upon hundreds of pages of official Spider-Man comics for Japanese consumption. Hell, English-language sources tend to differ as to when Ikegami's professional career even started.

What I'd like to do now is lay out a brief, incomplete, illustrated narrative of Ikegami's early years. There is an unfortunate lack of first-hand testimony available to the monoglot; I only know of one major interview with the artist in English, a 1993 talk with Satoru Fujii of the anime magazine Animerica (from which I will draw all quotations below). However, a good deal of Ikegami's early work is still available for purchase in Japanese print and digital form, and coupled with a collation of sources, few of them authoritative on their own, we might yet arrive at the beginnings of something approaching comprehension, if not the comprehensive. One imagines a bilingual student on location in Japan could supercede everything here with ease, and one prays they will, having been duly upset by my scrabbling.

--

Ryōichi Ikegami was born on May 29, 1944. Like not a few mangaka, his professional career began early; several online sources, including a short bio on the website of publishing giant Kodansha, positions his professional debut at 1961, which lines up with Ikegami's own recollection of starting out at the age of "seventeen or eighteen." His Chinese Wikipedia page -- Ikegami was a tremendous influence on the superstar Hong Kong cartoonist Ma Wing Shing in the 1980s, and as a result is well-known to inquisitive manhua readers of a certain generation -- relates some information I've not heard elsewhere: that he'd worked in commercial art, sign painting, since he was fifteen, and thus already had some experience in professional visual communication. It is unknown how many manga stories Ikegami sold as a teenager, though he's stated that it was work for the rental manga market. I only know of one reprinting of this material, as a bonus pack-in book to a deluxe collection of Ikegami's erotic illustrations(!) published by the used comics bookstore chain Mandarake some time in the'00s, but fan notations suggest that Ikegami may have continued to service the kashihon scene into the late '60s, after he'd come of age.

It is similarly unknown how many submissions the Osaka-based Ikegami made to Garo after its 1964 debut, but by issue #25, Sept. 1966, Ikegami had gotten a story printed: "Sense of Guilt" (as Animerica translates it), which Ikegami relates catching the eye of Shigeru Mizuki, already a popular cartoonist for his GeGeGe no Kitarō series of yōkai tales, but also a Garo contributor and mentor to the now-revered art comics master Yoshiharu Tsuge. At Mizuki's invitation, Ikegami left Osaka and sign painting to work as Mizuki's studio assistant in Tokyo.

As you can see, Ikegami's work in '66 is quite deformed in terms of characters, though it is not impossible to spot the older artist in the curvature of the sailor's sleeve in that bottom panel - compare with the Sanctuary image above, and you'll find his heavy, wavy line is unmistakable. And perhaps it was his eerie scratchwork backgrounds that piqued Mizuki, a great practitioner of the classic manga juxtaposition of simplistic characters against harshly realist backgrounds.

Know, however, that Mizuki did not keep his new charge on a leash. Ikegami continued to send work to Garo, where he became an established contributor prone to rapid leaps in progress.

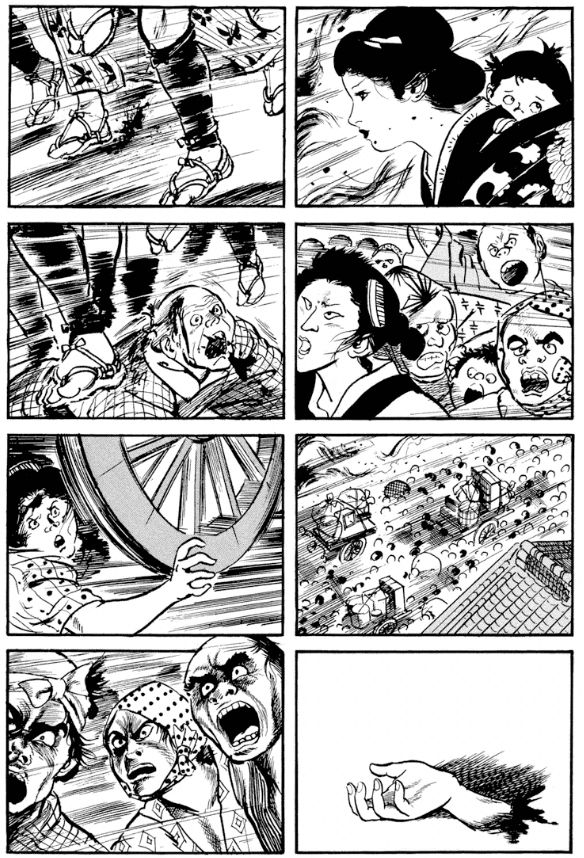

This is "Globe", from issue #37, Sept. 1967 - exactly one year later. Lacking testimony from anybody involved at the time, it is impossible to tell in which order Ikegami finished his contributions, but I think comparing these two signposts reveals an artist with a more confident command of space and layout, and particularly anatomy; while the character faces continue to look stylized, their doodle features are now pasted upon bodies of considerable verisimilitude.

As to the content of these stories, Ikegami seemed to favor creepy tales of angst and fate - surreal stories of disquiet. In 2010, Shogakukan -- essentially his 'home base' as a working professional -- released OEN, a 448-page compendium of Ikegami's personal favorite short stories from his early years at Garo and other magazines; if he did not exclusively produce weird, sad chillers in the short form, he apparently remembers those best.

Among the OEN selections, however, there is a notable outlier.

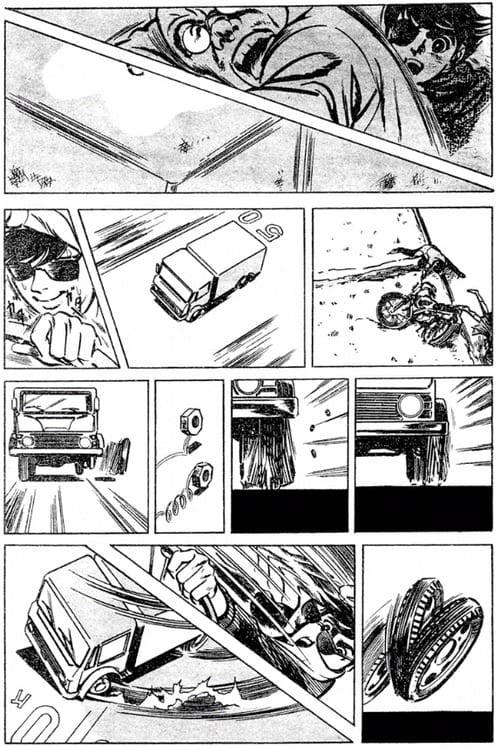

Among the Garo selections is this one from issue #44, April 1968, concerning in relevant part a bumpy truck ride where an older man and a one-eyed boy attempt to defuse a bomb. The one-eyed boy does not appear elsewhere in OEN, but he was actually a presence in a number of stories Ikegami summarily titled "Fuutarō" - this would be Ikegami's first attempt at a manga series.

It is a little uncertain how long the artist worked for Mizuki. Ikegami states that his tenure as assistant lasted "for two and a half years," and that the older artist granted him freedom "[w]hen I finally got my own serial... late in my twenty-fourth year." That would be mid-1968, suggesting (from the Sept. '66 publication of "Sense of Guilt") that Mizuki had probably seen the earlier story before it was actually published - which makes sense, given his comparatively wizened position to many of the Garo contributors. As to what Ikegami means by "my own serial," there are multiple possibilities, as 1968 saw him solicited by no less than three major publishers:

1. Most likely, he is referring to Tracker, a serial he mentions later in the Animerica interview. This was created for Shōnen King magazine, published by Shōnen Gahosha, which carries no mention of Ikegami on its site. In fact, I can find no record of Tracker having ever been compiled into book form - the only pictorial evidence I can find of its existence comes from an Ikegami superfan who collected a bunch of applicable back issues of the magazine itself and posted samples to Facebook. We can presume from the circumstances it was not an enormous success.

2. Around the same time, the aforementioned Shogakukan made its first contact with Ikegami, hiring him to produce another series, one of a fleet of tie-in comics to the spooky television drama Operation: Mystery! The same Ikegami devotee from #1 has posted samples of this work as well, from what looks to be a giveaway (or even bootleg) compilation. It says a lot that among the 145 Ikegami-related books on Shogakukan's site, there's no mention of this; it could be Ikegami himself has forgotten it existed.

3. Finally, Kodansha approached Ikegami with an offer to produce short stories for their weekly boys' magazine, the indicatively-titled Weekly Shōnen Magazine. This would be the second forum for Ikegami's early shorts, and if OEM is to be taken as a representative sampling of that work, there is remarkably little difference between the artist's output for an off-kilter revolutionary mag and an ultra-mainstream youth comics publication, though it seems Ikegami produced more 'period' work for the latter: Kodansha reprinted a number of additional samples in a 2003 two-volume series titled Ikegami Ryoichi Shugyoku Sakuhinshuu, and then released a bigger, one-volume collection in 2013, possibly with different content.

From this avalanche of output, we can presume that Ikegami likely went straight from assisting Mizuki to taking on assistants himself, likely receiving uncredited guidance from professional editors. Yet while the images available from Ikegami's early 'mainstream' series show a talented artist able to stick with the rigors of steady output, they do not betray a great deal of innovation; they are boys' comics, of the sort common at that time. At the same time, however, Ikegami seemed committed to the short form as a means of experimenting with new approaches.

He continued to contribute to Garo. See above is one of the most striking of his late '60s offerings: a story titled "White Liquid", notable not so much for its scenario of a man wandering a strange town fed by curious fluids -- 'guy traipses around, weird stuff happens' looks to have been a popular Garo plot, as it also describes Tsuge's immortal "Screw-Style" -- but for the delicacy with which Ikegami constructs the man's surroundings, both poetic and 'real' insofar as the artist seeks to capture the texture of nature ascertained through rain and murk.

And indeed, it was the "very realistic" quality of Ikegami's work that he credits with Kodansha handing him a new, high-profile, American-based serial assignment for 1970 - exactly the qualities that made him among the first to have his work exported to America in the following decade.

In his essay "Of Transcreations and Transpacific Adaptations: Investigating Manga Versions of Spider-Man", from the 2013 Bloomsbury collection Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads, Daniel Stein quotes from a 1978 issue of the Marvel fan magazine FOOM to the effect that while the company had attempted to simply translate its wildly popular new line of superhero comics -- still not yet a decade old -- directly into Japanese, the House of Ideas met with a wide enough cultural gap that it was decided to license the characters to indigenous publishers and artists.

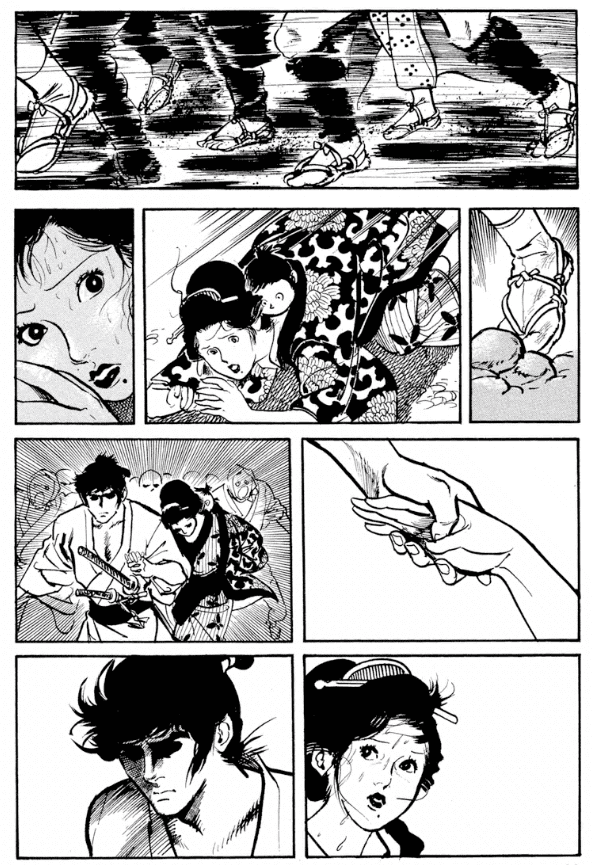

Naturally, Ikegami's Spider-Man is the only early series I'm going to mention today that's actually available in English; Marvel released a partial, edited translation in comic book form (as Spider-Man: The Manga) from late 1997 through 1999, and an unauthorized, unexpurgated fan translation has since been disseminated online. The reasons behind Marvel's ultimate editing of the material are simple to grasp: this is an extraordinarily odd, eccentric licensed comic, readily unlike what little can be glimpsed from Ikegami's earlier series in that it seems to have occupied a great deal of his time from 1970 to 1971, and served as a platform for a drastic darkening of his style.

Early on, Ikegami simply produced liberal adaptations of American comic stories, assisted by comics critic Kōsei Ono (because he could read English, while Ikegami could not). There's supervillains and web-slinging, if a fairly extraordinary amount of angst, even for Spider-Man. Per Ikegami, this was not a popular approach with readers.

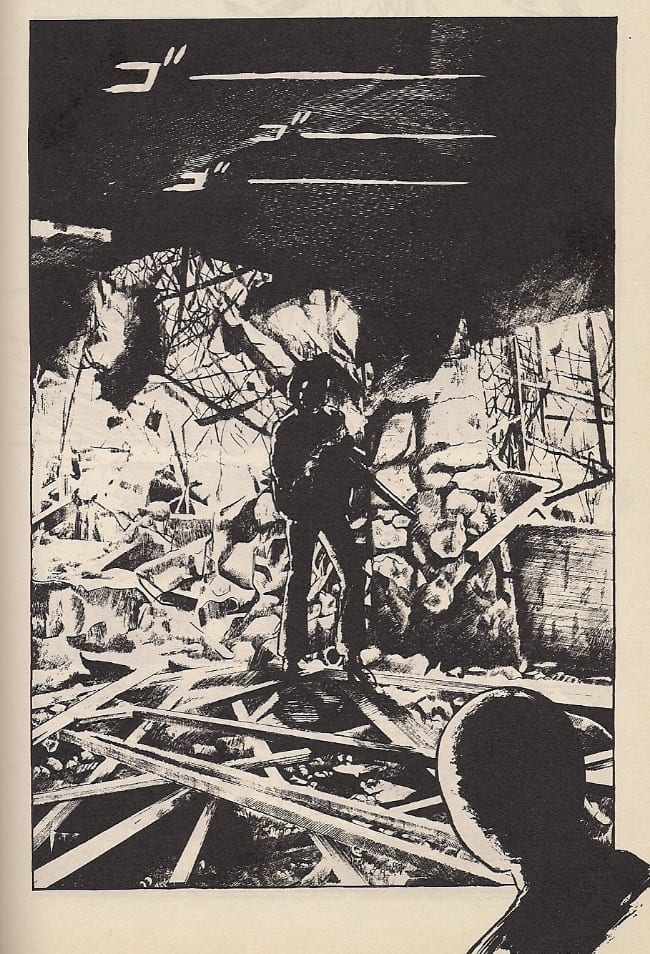

But then, on the advice of his editors, the SF writer Kazumasa Hirai was brought in to effectively script some Japanese appeal into thing, and Ikegami -- possibly sensing that nobody was reading anyway -- began to drive the series into incredibly bleak, dour territory, marked with tar-like blood, ambient sexual threat and the omnipresent specter of revolution in the streets.

Even more than his Garo works, Spider-Man was a kids' comic for a gekiga age, the sunny, romantic NYC of Jazzy John Romita replaced by the inky, sweltering ruin of Tokyo. We might call it tradition. We might say that Ikegami and Hirai turned back the clock to the seething paranoia of Steve Ditko, divorced from any leavening effect by a Stan Lee, but also subverted by a distinct sympathy for youth rage. These are angry comics; it's stunning they even exist, let alone that over 1,700 pages of them made it to print before, as Ikegami put it, "the cultural differences sort of did us in."

Yet they have remained quite visible in Japan; the most recent complete reprint, now with Media Factory rather than Kodansha, dates to 2004. And why not? That was the year Sam Raimi's Spider-Man 2 movie opened, and it is always with an international eye that these Hollywood behemoths are produced - there must be at least a little nostalgia for a distinctly local variant, reflecting the troubled time of its own creation, from a young artist, a future star, doing what he felt was necessary for his work and himself.

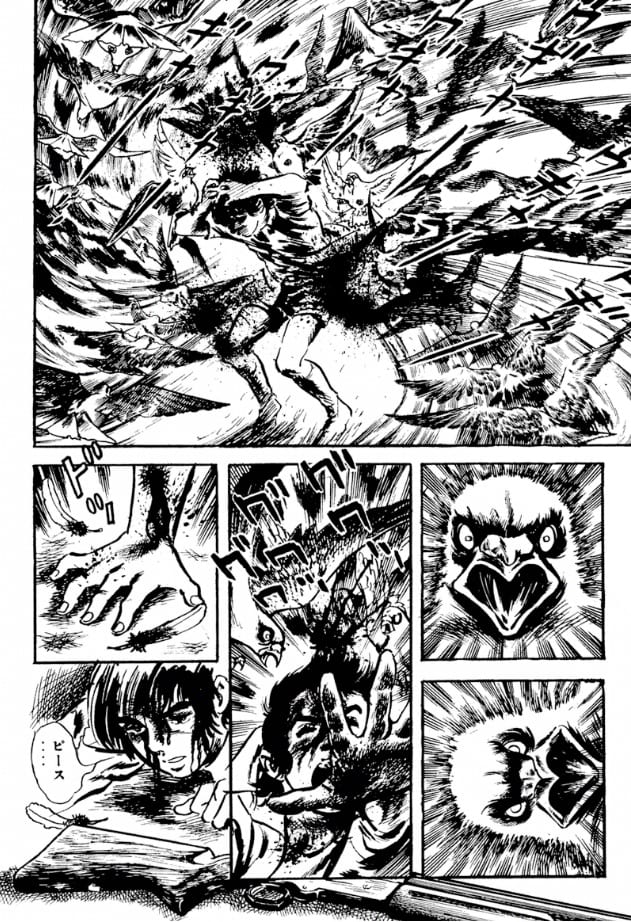

Following the '71 cancellation of Spider-Man, Ikegami continued to produce short works for Kodansha. By this point, the artist is fully into a median territory - not nearly so unique and mannered a realist as he'd be in the '80s, but obviously fascinated by the impact of overwhelming sensation. He'd also picked up quite a taste for blood - one 1971 Weekly Shōnen Magazine story finds a boy investigating a strange situation in which plucking the wings from butterflies results in the spontaneous dismemberment of nearby people. A 1972 piece, "Mad Pigeon" (my favorite), finds a gaggle of bullied children discovering the secrets of provoking birds to murderous rage, setting off a human/avian war which consumes the city, and ultimately themselves.

Ikegami also continued to produce period tales for the magazine, and it's there were we can best sense the 'mature' artist emerging:

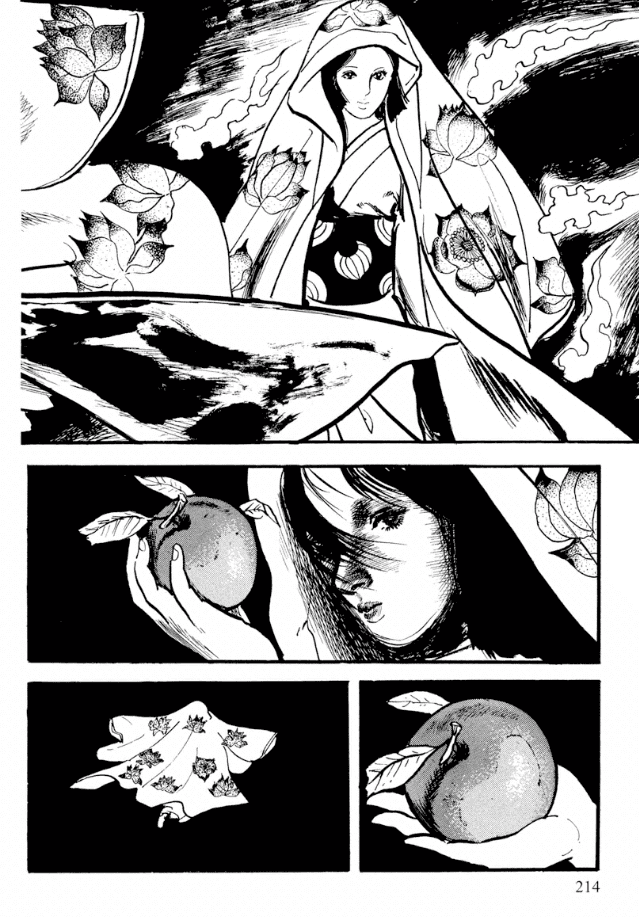

This is from 1972 - a yōkai story in which a group of men are menaced by a mystery woman offering fruit. I don't know if Ikegami was responding to trends or expectations regarding such fiction, but Ikegami did share space in Garo with the swordsman comics legend Sanpei Shirato, and Gōseki Kojima had been drawing the popular and influential Lone Wolf and Cub for two years already, and Ikgami's sensation is now built from brushy smears of ink bulked with hatches and crosshatches. Do, however, observe the amount of blank white in the woman's clothing in panel one, and the detailing of her face in panel two; combine them both, refine the face into something photographic, and you've got the modern Ikegami.

That said, we cannot presume these progressions weren't cold comfort to the artist, who'd not yet managed to maintain a series -- and with it, a more reliable source of income -- for more than two years. '72 brought another non-starter: a cycling serial for Weekly Shōnen Magazine, Hitoribocchi no Rin, with a novice writer, Tetsu Kariya, now best known for the cooking manga Oishinbo. At the same time, Ikegami returned to Garo for a serial all his own, which appeared in issues #102 through #108.

I know of absolutely nobody who has written about this project in English. The title is "おえんの恋", which I take to concern love and disease. The story sees a woman and a child navigating a difficult, feudal time, aided by a smoldering swordsman but menaced by the sexual exploitation endemic to the time. In the end, the woman throws the child from a bridge into the river.

And suddenly, things picked up. Kazuo Koike was the writer of Lone Wolf and Cub, and a fellow veteran of Marvel's Japanese experiment at Kodansha, where he scripted portions of Hulk. In 1973, he and Ikegami began to collaborate on a new series for Kodansha's Weekly Gendai - not a manga forum, but a general interest magazine, which was serializing mature comics like Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, by Ikegami's old mentor Mizuki. It was titled I Ueo Boy, a bottomlessly lurid thriller that set the pace for the duo's many manic contributions to come, and organized a... fitting universe for Ikegami's drawings to inhabit.

Then came an editor for Shogakukan. "[H]e liked my style," Ikegami said, "and wanted to see if that realistic touch could work in a boys' magazine." The artist teamed again with the young Tetsu Kariya, and the series they devised in 1974 was Otoko Gumi - now among the quintessential teen delinquent entertainments of the Japanese '70s. It was the comic that would make Ryōichi Ikegami a superstar. Soon, he and Koike had moved I Ueo Boy to Shogakukan as well. It was there that Ikegami would accomplish his final transformation.

But none of that is in English either. So it must wait.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Jim: Being a new 224-page, 7.75" x 11" Fantagraphics hardcover collection of Jim Woodring's personal, allegorical and autobiographical comics from the '80s & '90s, works which proved very mind-expanding to me, personally, through their treatment of conscious and subconscious realities as equally pertinent to funnybook memoir. Some of them are also really, REALLY funny - proper 'alternative comics'-era classics in here! Preview; $29.99.

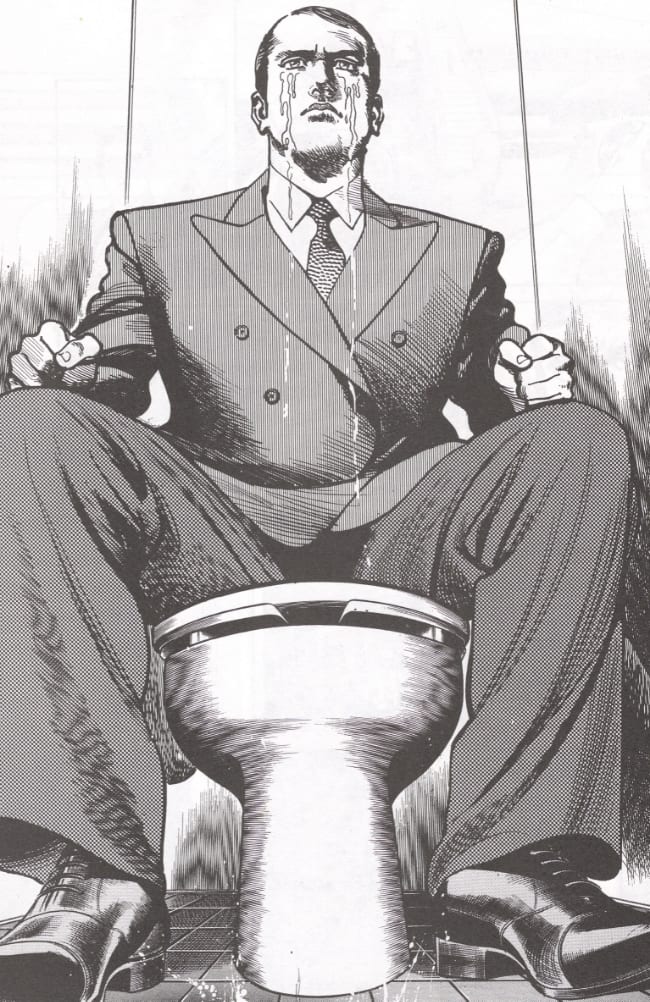

Demon #1 (of 21): And moving ahead to a new generation - it used to be that comic books were the primary platform for comics distribution, but now they're often more of a means to access audiences disinclined to search stuff out online. Hence, the 36-page beginning of a self-published, risographed, two-color 8.5" x 7" print serialization for the new webcomic by Jason Shiga, a clever and energetic storyteller here worked deliberately at "an incredibly slow pace" in detailing the saga of a man who can't quite seem to kill himself. The true nature of the story will not be revealed until later. Mail-order subscriptions available here (damn, this *is* a throwback); $4.95.

--

PLUS!

Lena Finkle's Magic Barrel: When people talk about the "Balkanization" of comics discussion -- and god help me, I think I may have introduced that term to the scene myself, sorry legacy -- they're talking about the circumstances that allow a book like this to be prominently discussed on NPR and the New York Times and a forearm-length accounting of additional generalist arts outlets without having much of any penetration into miscellaneous comics discussion. The author is Anya Ulinich, a Russian-born novelist, essayist and writer of short fiction who has also done some illustration work, and now makes her longform solo comics debut. The story juxtaposes a woman searching for romantic fulfillment with the Soviet childhood which shaped her. From Penguin, 368 pages in softcover; $17.00.

The Heart of the Beast: Your oddity from the vaults of history for this fading summer's week, a 1994 Vertigo original illustrated by the redoubtable Sean Phillips, already a veteran of the Suggested for Mature Readers school, and here working a blend of painted art and photography. It's a modern-day Frankenstein's Monster riff, written by Dean Motter & Judith Dupré, and now published by Dynamite as a 112-page hardcover. Preview; $24.99.

El Niño (&) Megalex: Two from Humanoids, the former of which hasn't been around in English since '05, and only then in incomplete form (as it hadn't yet been finished in France). It's a globetrotting tour of international hot spots with lots of chat about the humanitarian difficulties facing this world, powered by a woman-of-action searching for her lost twin brother, who seems to have become a notorious pirate. The writer is Christian Perrissin, he of similarly studious BD adventure fare such as Humanoids' Cape Horn, and the artist is Boro Pavlovic, of a classy, statuesque Eurocomics aesthetic. The entire 2002-09 series (acutally a series and a sequel, I think) is here, a 392-page(!) 7.9" x 10.8" hardcover. Megalex, meanwhile, is a reissue of what's candidly among the weaker Alejandro Jodorowsky projects available in translation, although Fred Beltran's full CG art for 2/3s of it (and the fact that he eventually stopped) may prove historically interesting. Digital editions are available for everything. Niño preview, Megalex preview; $44.95 (Niño), $29.95 (Megalex).

The Smurfs Anthology Vol. 3: Continuing NBM/Papercutz's 8.5" x 11" hardcover line of vintage Belgian work by Pierre "Peyo" Culliford, including "The Cursed Land", a 1964 Johan et Pirlouit album appearing in English for the first time. Plus: a shit-ton of Smurfs across 192 pages; $19.99.

Scott Pilgrim Color Hardcover Vol. 5: Scott Pilgrim Vs. the Universe: And then comes Oni with their own hardcover project, a colorization of Bryan Lee O'Malley's affaire du '00s, still at 6" x 9", and bulked up to 192 pages with commentary and extras; $24.99.

Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 8 (&) A.B.C. Warriors: The Volgan War Vol. 4: Two from 2000 AD, the former a Simon & Schuster collection of mid-'80s material written by John Wagner & Alan Grant, the latter a Rebellion softcover edition of the conclusion to a huge Pat Mills/Clint Langley robot storyline with a heavy digital look. Dredd samples;

Dark Ages #1 (of 4): But the sun never truly sets on 2000 AD contributors, as writer Dan Abnett (of not a few useful ideas in the Guardians of the Galaxy film) and I. N. J. Culbard (the airy, colorful artist of Brass Sun) present this new Dark Horse miniseries, concerning medieval warriors facing off with SF beasties. Will probably look nice. Preview; $3.99.

The Tower Chronicles: DreadStalker #1: Also from a 2000 AD champ - Simon Bisley draws an ongoing monthly series! At least, Bisley's the only artist I can find associated with the project right now. It's a continuation of an earlier project Bisley did with writer Matt Wagner, from Legendary; $3.99.

Wolfsmund Vol. 5: Continuing manga pick, courtesy of Mitsuhisa Kuji's saga of violence and struggle in the Swiss Alps, much brighter in terms of drawing than a Ryōichi Ikegami, but possessed of its own special, ugly kick. From Vertical; $12.95.

Dave Gibbons' Watchmen - Artifact Edition: Finally - no, not an artist's edition, but an Artifact edition, since the whole of this Alan Moore-scripted superhero maxiseries is not going to be presented. Rather, it's 144 pages of 12" x 17" images, scanned in color from Gibbons' original b&w art with lots of promotional and supplementary pieces. Plus, lots of added fun in seeing if the Original Writer is mentioned by name; $100.00.