The first publication released by Savoy Books, in 1976, is said to be Stormbringer, a "graphic version" of Michael Moorcock's early stories of Elric of Melniboné by the artist James Cawthorn. Specifically, the work was published by David Britton, a bookstore proprietor who'd been involved in small press magazine printing and editorial since 1969; one of the first works he'd released was a suppressed comic by Ken Reid, which had been passed along by Steve Moore, the future mentor of an unrelated Alan. Before long, Britton would combine his energy with that of Michael Butterworth -- not the Mike Butterworth who wrote Vampirella as "Flaxman Loew" in the '70s, but a contemporaneous author/editor/publisher -- and, through several iterations of the Savoy legend, would release books, records, and comics, the most recent of which arrived in 2013: Lord Horror: Reverbstorm, a 344-page hardcover compilation of work dating back nearly 20 years.

It was scripted by Britton himself, from a scenario by Butterworth, the editor, and drawn by John Coulthart, also the book's designer. Despite praise from the aforementioned Alan Moore, I don't recall any of this work, in any format, being distributed to North American comic book stores through traditional comic book distribution channels, nor can I recall much of anything in the way of sustained critical attention from comic book specialist avenues.

But already, in puffing myself up, I have made an error. The first 32 pages of the collected Reverbstorm are taken from a yet-earlier Savoy publication - one of the most curious horror comics of the 1990s.

To understand Lord Horror #7, aka Hard Core Horror #5, aka King Horror: Zero, copyright 1990, it is crucial to know that David Britton had been to jail once, in 1982, and would be jailed again in 1993, both times for selling obscene material; Savoy's bookshops had been raided by police on a steady basis since '76, the year Britton began publishing. Most infamously, a 1989 raid seized copies of Britton's debutante prose novel, Lord Horror, a surreal conflagration of fascistic exaggeration loosely based on the WWII persona of William Joyce -- dubbed "Lord Haw-Haw" by the British Press -- an Irish-American resident of England turned naturalized German who helmed British-targeted propaganda broadcasts with a sneering, mocking glee which rendered him something of an evil celebrity among the aggrieved. Britton had debuted his "Lord Horror" variant on a 1986 Savoy-published New Order/Bruce Springsteen cover record, the sleeve of which depicted James Anderton, the severely religious chief constable of the area, uttering racial slurs whilst the back of his head exploded.

Anderton was among the figures alluded to in the pages of Lord Horror, which, from the excerpts I have encountered in print and audio form, trafficked in a swirling perceptual mist colored entirely by the hatred of its monstrous, fantastical and not entirely uncomic title character, who at one point, wandering a neon-lit NYC like an immortal champion of anti-Semitism, snatches a fully-grown leather-and-enema sex pervert and gobbles him up like a hungry hippopotamus. The book was found obscene by a local magistrate, and, though the ruling was overturned the following year, at least sparing the impounded stock destruction, it has never been reprinted, save for a 1995 edition released only to the Czech Republic. For those interested in reading further, I recommend David Kerekes' exhaustive study of Savoy's travails, which, via accumulation, depicts the applicable obscenity prosecutions as less civic-minded adjudication than a fabulous, generation-spanning local beef with one side empowered to seize both property and liberty from the other.

There were also comic books: Lord Horror, begun the same year as the novel, depicting the further adventures of the title fiend; and Meng & Ecker, a more overtly comedic 'bad taste' spin-off which suffered its own obscenity ruling alongside the Lord Horror novel. Both series were written by Britton and drawn by Kris Guidio, until (to repeat myself) the seventh issue of Lord Horror, which concluded a sub-series, Hard Core Horror, which anyway functioned as a standalone unit entitled King Horror: Zero. It is a magazine-sized 8.5" x 11.75", well-produced with a glossy cover and good paper, 60 pages in black & white.

It is, in effect, a work of thorough deconstruction.

--

King Horror begins on its inside front cover with photographic images of Jessie Matthews, an actress familiar to British audiences of the WWII period - famous, in part, for her scandalous romantic life. The images are accompanied by text, fiction, noting her marriage to Horace Joyce, Lord Horror: glamour intertwined with disgust. "He really loves her, and she loves him," muses James Joyce, fictive brother of the title villain. On the facing (first) page, we then see a photographic blow-up of Matthews' face, on which is overlaid historical text detailing the tremendous, disgusted renown of the real William Joyce, at the time of his trial on charges of treason, despite not actually being a citizen of England. Two popular images.

Then, horribly, we are seeing photographic images of ovens. Overlaid are texts relating to the creation of the "Lord Haw-Haw" name by journalist Jonah Barrington, a title eventually embraced by the in-character propaganda broadcasts of Joyce himself, so that fictive reality came to embrace a deeper fiction; all the better to tease the paranoia of reality, since part of the impact of such broadcasts was that they were meant to be taken as emanating from within Britain. Next, we read an excerpt from a 1941 novel by Brett Rutledge, depicting the heroic killing of Lord Haw-Haw - fiction again rising to fiction. The shock of reality subsequently arrives, as the photo-backgrounds depict heaps of starved corpses while the text details testimony as to the oratorical prowess of Joyce, the man behind the character; interspersed is sarcastic commentary by Barrington, who himself sought to fight back this menace with ridicule. This is a war of bodies and minds, each represented by image and text, the fundamentals of comics, but at different times. The prelude ends.

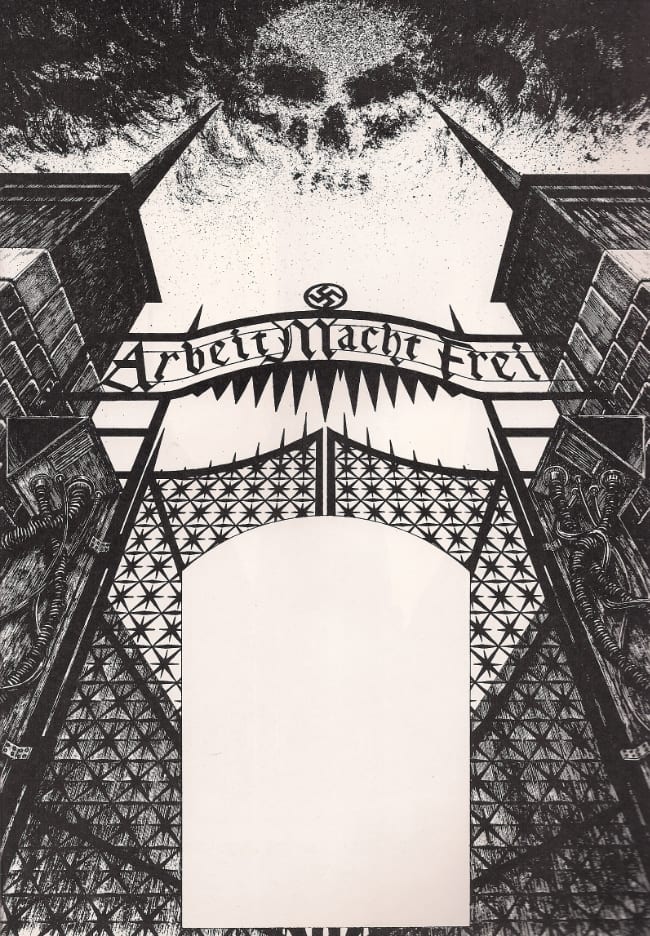

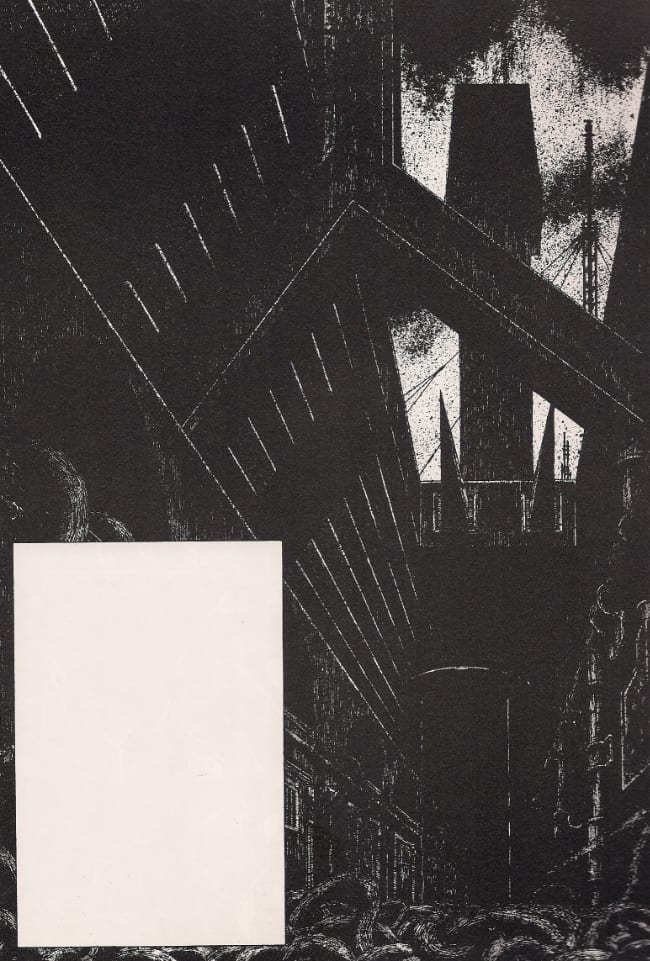

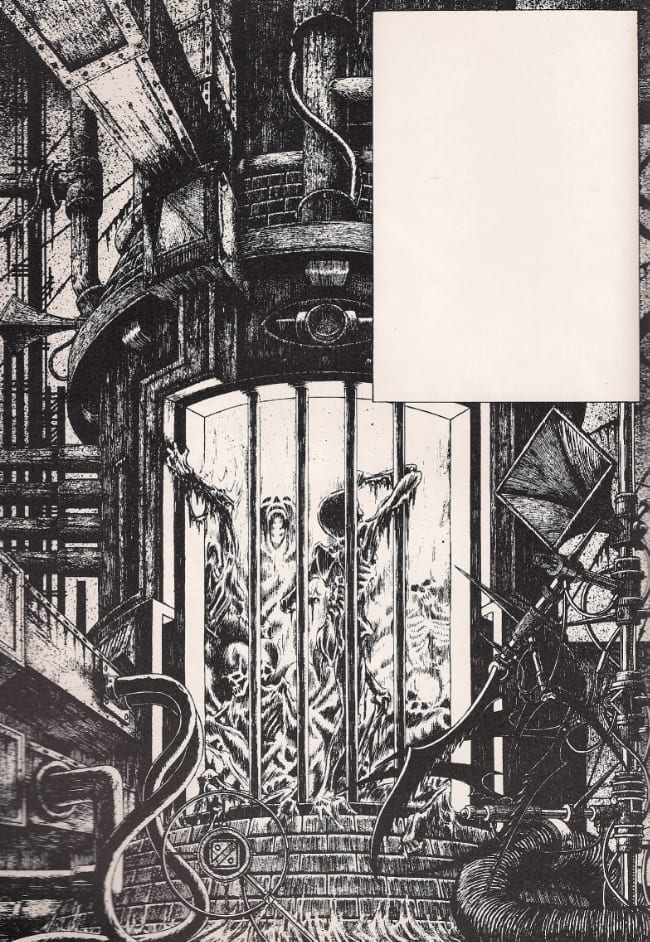

John Coulthart's ink-on-paper contributions to King Horror can be messily identified as architectural or industrial drawing. For 32 pages, we are shown full-page or double-page renditions of settings, very occasionally with the absurd, tall-haired silhouette of Lord Horror lurking about. It is evident, quickly, that this is a concentration camp: "Arbeit Macht Frei." Savoy begs comparison with the etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, while generous comic tragics may cite to Martin Vaughn-James' eerier, wordier 1974 graphic novel The Cage, but the most obvious comparison issues from a comics artist famously reliant on background support: Dave Sim, of 2008's Judenhass.

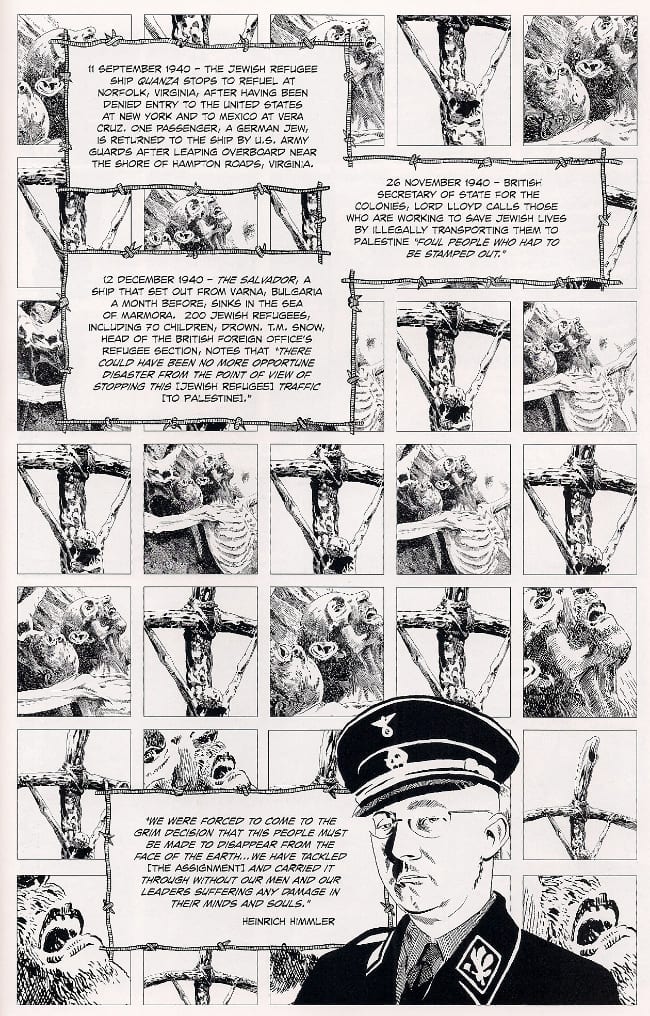

The departure of aesthetics between these two early images is self-evident. Sim, by his ready admission, is working from specific, cited photo-reference. The image is cold and mechanical, by design. It seeks to groan with the burden of witness, and the fact of its deliberation will become the heart of the Judenhass project.

Taking a small handful of photographs and copying, detailing, excerpting and collaging, Sim creates a distinctly literal type of poetics. Tiny panels of damning bodies underlie quotes taken from brightly-illustrated famous faces, positioned for maximum anti-Semitic horror impact - these are the consequences of such words. That Judenhass was questioned as to the causative value or basic applicability of these words is natural, since every page of it is pedagogical, instructive.

Coulthart's images, meanwhile, are disquieting in their vivid imagination. These are *not* drawn from photographs (which the comic has already demonstrated are easy enough to print on their own); in their looming black spires and smooth vintage contours, they look fit for a genocidal episode of a superhero cartoon from the Bruce Timm era. See an ashen skull grin in the skies above these gates! Eerie tendrils writhing down a dread, yawning hall! In these moments, one can imagine the dismay of Manchester's moral guardians, grudges aside, because Coulthart, also an illustrator of Lovecraft, is making these images awesome, in the sense of inspiring awe, which can easily read as tribute. I feel it is more about emphasizing the unique qualities of drawing versus the mechanical capture of photography; both can be visceral, sensual, hallucinogenic, but drawn images in sequence can better absorb, because in lacking the blunt sensory recognition of 'reality' they can be accepted instantly as allegorically 'real' - as places.

But note too the blank spaces of white occupying each page. These are empty captions; they are the indication of explanation, or at least accompaniment, or counterpoint, or something, but without any substance. This is not the same as merely presenting images - here, images are explicitly split off from text. And, when read in conjunction with what has come before, and what will come after, the suggestion is made that images can be both concrete and subjective. As I mentioned before, this segment of King Horror (printed darker, with some extra strokes of shading added, and one image inverted) would eventually become a prelude to the collected Reverbstorm, which indeed planted its cast of characters into an Auschwitz by way of Gotham City, dislocating [h]orror from a specific time and location and declaring it everywhere - like threat made stone. And if it all threatens to look like an album sleeve, well: isn't this a comic anyway about image and excitation?

Again, the poles reverse. Coulthart withdraws and Britton enters for five pages of white text on black paper. It's a rambling, dense screed, depicting Lord Horror's inquisition of himself regarding the suicide of his wife, Jessie Matthews, and, among other things, the suspicion that the microbes clamoring on his hand are Jews - all this despite him being costumed as a rat, the bringer of plague. Aloud, Horror wonders if genocide isn't a biological imperative. "All things are to be counted good that are done according to nature," says Cicero, below the issue's title. Yet suicide is to yield "to the mind's jungle." Is it, then, good? The annihilation of the 'beautiful' image, Matthews, before the horrific?

I cannot promise you will not be somehow left wanting by these provocations. This is a comic, after all, which concludes with 15 pages of sequential images of photographs of corpses, as both a reprisal of its prelude and a final lunge into questioning images. Here, we react: we recognize these as bodies, instantly, though we are never told that they are victims of the Holocaust. They are overlaid, instead by two additional elements. There are brief factoids, detailing more of the life and influence of Lord Haw-Haw, supporter of all this. And there are also measurements: musical scales and the like, drawn over the bodies. This is the futility of art, perhaps, to account of these physical and psychological horrors. Or maybe it is a leap toward accounting for everything - the final page sees a nude, dead man with a star chart drawn over him, reminding us that we are all carbon-based entities, just matter, and threatening that pain and horror and suffering and hatred and death are endemic to our condition, and that it will continue well past humanity and its affairs, upward and into infinity.

***

PLEASE NOTE: What follows is not a series of capsule reviews but an annotated selection of items listed by Diamond Comic Distributors for release to comic book retailers in North America on the particular Wednesday identified in the column title above. Be aware that some of these comics may be published by Fantagraphics Books, the entity which also administers the posting of this column. Not every listed item will necessarily arrive at every comic book retailer, in that some items may be delayed and ordered quantities will vary. I have in all likelihood not read any of the comics listed below, in that they are not yet released as of the writing of this column, nor will I necessarily read or purchase every item identified; THIS WEEK IN COMICS! reflects only what I find to be potentially interesting.

***

SPOTLIGHT PICKS!

Benson's Cuckoos: Comedy! It's what we're all about. This is the new one from Anouk Ricard, whose Anna & Froga series has seen three volumes released by Drawn and Quarterly; the same publisher is involved, but Ricard's aim is purportedly more adult, targeting strange, childish behavior in an office environment. It's 96 color pages in a 6.5" x 9.5" paperback. Preview; $19.95.

Magic Whistle #14: And here is Mr. Sam Henderson, following up two consecutive years' worth of issues with another new one, courtesy of Alternative Comics. Expect 32 b&w pages of laughs and good times in the manner to which you have become accustomed; $4.99.

--

PLUS!

Usagi Yojimbo Color Special: The Artist: Being a 32-page collection of recent color stories by Stan Sakai, culled from various print and online iterations of Dark Horse Presents - the publisher's solicitation deems it a good entry point for this looooong-running anthropomorphic animal samurai series, which is due to see an SF-styled future timeline story begin next month (a previewe of that should also be included). Samples; $3.99.

Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me: This one's a softcover reissue, which I don't usually mention, but it's a pretty light week, and I think it's good to draw attention to an alternative, super-direct means of addressing issues of Jewish history and identity. Of course, the writer is Harvey Pekar, in one of his final efforts, with art by JT Waldman. From Hill and Wang; $16.00.

POW! - A Peanuts Collection (&) Pearls Before Swine: The Croc Ate My Homework: A pair of Andrews McMeel paperback collections for comics old and new. I keep forgetting that Peanuts reprints have been coming from this direction since 2013, and POW! is a 224-page, 6" x 9" baseball-themed slice of that (could make for an interesting pairing with Fantagraphics' Batter Up, Charlie Brown! collection from a few months back). Croc is the same length and size, devoted to the well-regarded Stephan Pastis strip; $9.99 (each).

Moomin: The Complete Lars Jansson Comic Strip Book 9: Reprints of a more deluxe breed, an 8.5" x 12", 112-page hardcover from Drawn and Quarterly. I don't know the years off-hand, but we've got to be nearing the completion of this project. Samples; $19.95.

The Flowers of Evil Vol. 10: In which Vertical continues its translation of Shūzō Oshimi's perverse interpersonal relationship manga, which just recently wrapped serialization in Japan. I *think* that should position vol. 12 as the official finale; $10.95.

Hondo City Justice: Revenge of the 47 Ronin: Another Simon & Schuster U.S. homebrew collection of Judge Dredd stuff, which is to say another book with rather ambiguous contents. It's definitely 160 pages, definitely focused on the future Japan of the series' world, and -- judging from the subtitle -- featuring some pretty new work, such as a (nicely-drawn) Robbie Morrison/Mike Collins/Cliff Robinson serial involving undead warriors; $19.99.

Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (&) It Happens at Comic-Con: Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon: Finally, here are *two* McFarland-published academic books-on-comics for the week. The first is a 268-page Julia Round study of "the connections between comics and Gothic from four different angles: historical, formal, cultural and textual... with particular attention to the DC Vertigo imprint." The second is an anthology, edited by Ben Bolling and Matthew J. Smith, examining cultural practices at the San Diego event "from the practices of fans costuming themselves to the talk of corporate marketers"; $40.00 (Gothic), $35.00 (Comic-Con).