So, brass tacks - what the hell is the Doom Patrol anyway?

Let’s really ask the question, because I think it’s a question Grant Morrison thinks is really important. The Doom Patrol was DC’s first really sincere Marvel Comics rip-off, and as with all durable imitations it gets some things about the original precisely right and some other things endearingly, and productively, wrong.

In the context of the times its important to remember that the message at the heart of Drake and Premiani’s original Doom Patrol stories was notable for its boldness and prescience - that is, disabled, disfigured, and otherwise different people can contribute to society as well as normal folks can. Can you hear the problem? The problem with the idea of the Doom Patrol at its heart is that even if in-text it could be said to have championed a very progressive message, what seems progressive to one era can seem helplessly regressive to another. And the fun part of that statement is that it serves nicely as a critique in hindsight of the Morrison era as well as a summation of some of Morrison’s most significant themes.

After all, the real villain at the end of the story is Niles Caulder himself, the Chief. A man who went full super-villain in plain sight of the whole team. And it’s not like it’s completely out of the blue, or even really inconsistent with the Chief’s behavior in past incarnations of the team. He’s kind of an asshole even to the people he’s helping, in a way that can’t help but seem suspicious. His heel turn makes sense. It’s a concept that has to refute itself to have any value. The Chief is ultimately as much of a Malthusian windbag as General Immortus himself, a selfish accelerationist secure of nothing but that he won’t have to clean up whatever mess he makes. It’s the kind of attitude that might seem familiar from the daily news - “weird eccentrics who think they have the right to play god with the lives of billions” exist in this world too, after all, we call them “billionaires.” They’re easy to find, they’re the people with the moral reasoning of concussed toddlers.

The people who are always left to clean up the damage are invariably people like Cliff. Everyone loves Cliff. Everyone knows Cliff has had a rough go of it, everyone sees him as a straight shooter. He gets respect even from the normie heroes because he’s seen it all and done it all. He’s Ben Grimm in the DC Universe. Difference is, the Thing is surrounded for most of his career by the bosom of a loving and supportive family that generally keeps him from going off the rails. Robotman is surrounded by a cast of close friends (who have a habit of dying) and loose associates (who also have a habit of dying), and some of the people who die come back different and sometimes they come back as genderless composite beings. There’s also usually a guy in a wheelchair with kind of a bad attitude about the whole thing. It’s enough to drive a man to drink, except he can’t. Because robots can’t drink, which seems like a real flaw in Caulder’s original creation.

Morrison’s version of the team ultimately repudiates its creator when they recognize that he’s gotten older and weirder in a bad way. The version of the Doom Patrol as a group of depressed, self-pitying self-styled “freaks” couldn’t survive contact with the reality of world where the freaks didn’t want to be so sad all the time anymore, and didn’t necessarily understand why they had to compromise, either.

Morrison’s version of the team ultimately repudiates its creator when they recognize that he’s gotten older and weirder in a bad way. The version of the Doom Patrol as a group of depressed, self-pitying self-styled “freaks” couldn’t survive contact with the reality of world where the freaks didn’t want to be so sad all the time anymore, and didn’t necessarily understand why they had to compromise, either.

Every version of it since Morrison has existed in Morrison’s shadow - either benignly, as with Rachel Pollack’s underrated run, or hostilely, as with Byrne’s run. Even the Arcudi run - long a series I’ve championed as an overlooked gem - as smart and clever a book as it was, was just not what people wanted, not with Morrison’s run not (checks notes) nine years previous, with the conclusion of the series and Pollack’s run not two years after that. Too soon? Apparently too soon.

Now, with that said, why was Morrison’s run on the book disliked so intensely by a certain group of very vocal creators? The Morrison run changed the team completely in ways that went beyond merely superficial line-up changes. The characters had become different people with different personalities. They couldn’t do the same kinds of stories that they used to with the Doom Patrol, because all the original cast had become unrecognizable (or, like poor Rita, stayed dead). They weren’t going to be any feasible “back to basics” arcs with the team in their old sixties togs. The series had changed itself by refuting large parts of itself.

That pinpoints a real tension at the heart, not just of the Doom Patrol, but of any long-running franchise. No matter how “progressive” - and I use that word here with scare quotes because it can mean a lot of different things - no matter how progressive any story may be, elements of social commentary will eventually take a back seat to the more conservative desire simply to create something that looks like it used to look. Even if the toys don’t really work the same way now, because the world around them has changed, and they look kind of silly out of their original context. The desire to freeze characters and concepts in amber, to capture them at the precise moment of their supposed zenith, is what ultimately kills them by turning them into nostalgia objects. It may please anyone who remembers the “old school” to see all the pieces back in their right place, but it’s very hard to catch new fans with the breath of the tomb wafting through the rafters.

Not everything changes, of course - Cliff stuck around, because Cliff always stuck around. He’s a stand-up kind of guy. But he also undergoes consistent change himself over the course of the series in general and Morrison’s run in specific. He works on himself and eventually learns deadnaming Rebis is kind of rude. You don’t get to stick around in the Doom Patrol if you just want to spew the same regressive bullshit, if you’re going to stay you have to at least try to become a better person, or at least have the good grace to die in an Invasion! crossover.

Everything changes all the time, of course, but change rarely has the good graces to follow our expectations. It’s a familiar observation to note how unwieldy and bulky the communicators on the original Star Trek actually are, especially as you’re likely reading this essay on a device that makes the one on the fictional sci-fi program look like a kids’ toy. Similarly, the character of Rebis - a genderless composite entity formed by the former Negative Man Larry Trainor, Dr. Eleanor Poole, and the strange energy being whose powers Negative Man summons - seems like such an unwieldy and bulky approach to coming out as non-binary. It’s hardly as complicated as all that. You can even get an ‘X’ on your license in some states. Flash fact!

Does it make the character of Rebis “bad” in some way to point out that its slightly dated simply by nature of, again, almost three decades of an increasingly weird world getting ever delightfully weirder? Nah. Much like Neil Gaiman’s Desire, the fact that the genderless character is more or less a creature of complete fantasy keeps them safe from any kind of condescension, even the well-meaning kind. They get to be cool, not avatars of sorrow or cautionary tales or giggly jokes. In this respect, for me, it’s hardly disrespectful, just dated. But dated it is, simply by dint of living in a world where events once conceived as the bleeding edge of strange have found themselves reflected in the mirror of reality.

Speaking of which - since this is as good a place as any to randomly insert a paragraph about a character who is himself a random insertion in so many lives - can I just talk a minute about Mister Nobody? Everyone talks about “The Painting That Ate Paris” but it was actually the second Mister Nobody story that caught my eye this time around. I barely remembered what happened in it, having read it last well over a decade ago. But the story of a dada-spewing chaotic narcissist surrounded by bumbling henchmen harnessing America’s simmering discontent with the system into a massive protest Presidential campaign hits a bit different now than it used to.

Speaking of which - since this is as good a place as any to randomly insert a paragraph about a character who is himself a random insertion in so many lives - can I just talk a minute about Mister Nobody? Everyone talks about “The Painting That Ate Paris” but it was actually the second Mister Nobody story that caught my eye this time around. I barely remembered what happened in it, having read it last well over a decade ago. But the story of a dada-spewing chaotic narcissist surrounded by bumbling henchmen harnessing America’s simmering discontent with the system into a massive protest Presidential campaign hits a bit different now than it used to.

Trompe le Monde

I guess it speaks well for the work when so much in it proved, if not precisely prescient, at least relevant to the early twenty-first century? Dated or not, Morrison anticipated a great deal of what would be important today. That counts for something, certainly. Dada is not a symptom of a healthy system. Dada bubbles up in protest against inhumanity and deadly spectacle. There’s a lot of online humor now that purposefully aims at something similar to Dada - insular, full of opaque references (more often than not non sequitur), purposefully nonsensical, and resolutely anti-commercial. It’s harder to commodify nonsense, but not impossible.

The example of Millennium is important, I think, for understanding the small-p politics of the post-Crisis DC Universe. If you haven’t read that story - from late 1987 and 88, for context - it’s got two main thrusts: the elevation of humanity to a new evolutionary plateau in the universe juxtaposed against the discovery of a conspiracy, millions of years old, to replace key people across the universe with villainous Manhunter sleeper agents. Lana Lang turned evil, and so did the great god Pan (probably news to Plutarch). If you wanted a perfect example, in one chunk of comics, of just what it means to say “DC Comics took a remarkable right turn after Crisis,” just look at that story: Steve Englehart’s very sincere and somewhat New Age-y musings about the nature of man and the universe have to make equal time for a galaxy-spanning conspiracy complete with sleeper agents poised to deliver intimate betrayal to the most American of heroes.

What is true for DC is true for much of the culture at the time. The fact that Reagan won not one but two elections - by increasingly wide margins - and was able as well to leave his Vice President with a very easy route to a third Republican term - really got in peoples’ heads across the left and center. The imaginative frontiers of the country shrank accordingly to fit a blinkered and paranoid epistemology. Everything started to look a bit like a cheap TV show. 1988 saw the death of the second Robin at the hands of vengeful fans, via a telephone poll - itself a bad sign of our national conscience, it should be said. But the weirdest part of that story, by far, is the part where Iran makes the Joker their ambassador to the United Nations, right before the Joker uses that opportunity to try to kill the General Assembly.

There’s a reason why I spent so much time earlier talking about the context of Morrison’s Doom Patrol: it’s important to remember that he didn’t start the book from scratch with a blank slate. He inherited a poorly performing relaunch of a Silver Age idea that had never really been much of a commercial draw in the first place. Stories are like fashion, and fashion tends to repeat in 20-30 year cycles - if there’s a reason everything now looks like 1992 to you, you might have noticed that torn jeans, flannels, and Doc Martins with dresses are in again. The Cold War (which had obviously never left) came roaring back in the 1980s across all branches of pop culture, something I think a lot of people already understand - but part of the reason it came back was because it was familiar to the Baby Boomers who were then currently riding high as the dominant demographic reality of the English speaking world. After a couple decades of national trauma, folks wanted villains they could hiss at again without feeling in some way implicated.

Remember “Alternative” as a category? It was a marketing ploy that had to be invented partly because thirty-and-forty-somethings were refusing to let go of pop culture, the mainstream of which was and remains a wellspring of corporatist defeatism masked as entertainment. The only reason they needed to call rock music or indie film or weird comic books “alt” was because grown-ups now had no problem listening to rock & roll or still trying to be cool, albeit with cars and jobs and money. They needed a different brand for the kids still coming up with no interest in Bruce Hornsby, and who perhaps sensed, even then, that their economic horizons were going to be rather more limited than originally conceived.

(Of course, “alt” itself superseded the previous “college” as genre signifier for anti-mainstream music and culture. But out of context that makes even less sense than “alt.” And it makes especially less sense now that much of the period’s supposed “alt” art has become more widely remembered and discussed.)

That’s the context for Doom Patrol: a whole generation was growing up, becoming active in the culture, and entering the workforce right in time for the previous generation to decide, yeah, we’re literally just going to keep running everything into the ground. Past the general party vibe of the Clinton & Blair years (don’t bother looking under the floorboards, corpses as far as the eye can see), “alt” culture in the 90s seethed with the frustration of being virtual passengers aboard a slowly scuttling vessel that just happened to be the whole world. That’s one reason Morrison’s run remains unsettling: that vessel is still scuttling, and for many of the same reasons. The Boomer catastrophism that underpins Niles Caulder’s turn towards supervillainy is literally guiding the federal government today: things are terrible, everything is changing, best just to jam the accelerator because then at least we get to control the fear.

The value of the Doom Force is as a thematic overture to the main series. The villains in that one are also genocidal terrorists accelerating the end of civilization.

And here we reach the generation schism at the heart of Morrison’s run: in the face of paleo-conservative panic over the changing world, the Doom Patrol exist to point out that one man’s Armageddon is literally just another man’s tomorrow. The change and foment that accompanies social progress - the franchise’s most enduring theme, even if not every creator strikes the note evenly or intentionally - splits society down the middle. The Doom Patrol is inherently political in a similar manner as the X-Men: the villain is ultimately just old people who refuse to change their minds. The garden path to fascism is paved with men and women who see social change as a breakdown of order and tradition. Disabled folks who refuse to sit and suffer in silence for their sins are just as much a threat to the system as queer people or people of color who refuse to take their oppression with a smile.

The end of history foretold at the end of the Cold War was always harmful and selfish illusion, born as it was of a conviction that all the major battles of human history had already been won. As it turned out, that was not true. It was patently absurd on the face of it in 1992 when Fukuyama wrote it, and for proof of this rebuttal I offer as evidence the aforementioned Doom Force special, published the same year. Clearly the end of history was not at hand, not when Fukuyama’s vaunted “universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” was already put paid by the fact that the kids writing weird comics were clearly spelling out the means by which the future would be contested by non-state actors operating along ideological lines - i.e., far-right terrorists who react to institutional stasis and lethargy as an open invitation to disrupt non-functioning status quos. Add in the imminence of multiple existential threats - not just ecological in nature, but that’s the elephant in the room - and rather than an ending to the filthy scrum of history what we see is the birth a far more chaotic twenty-first century than anyone expected. The forces that constrained and withered Western democracy over the span of its existence as a form of government - essentially, corruption and the concentration of inherited wealth - see no margin in obeisance to the ideals of plurality and compromise. Especially when, in terms of real numbers, they’re so outnumbered.

The end of history foretold at the end of the Cold War was always harmful and selfish illusion, born as it was of a conviction that all the major battles of human history had already been won. As it turned out, that was not true. It was patently absurd on the face of it in 1992 when Fukuyama wrote it, and for proof of this rebuttal I offer as evidence the aforementioned Doom Force special, published the same year. Clearly the end of history was not at hand, not when Fukuyama’s vaunted “universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” was already put paid by the fact that the kids writing weird comics were clearly spelling out the means by which the future would be contested by non-state actors operating along ideological lines - i.e., far-right terrorists who react to institutional stasis and lethargy as an open invitation to disrupt non-functioning status quos. Add in the imminence of multiple existential threats - not just ecological in nature, but that’s the elephant in the room - and rather than an ending to the filthy scrum of history what we see is the birth a far more chaotic twenty-first century than anyone expected. The forces that constrained and withered Western democracy over the span of its existence as a form of government - essentially, corruption and the concentration of inherited wealth - see no margin in obeisance to the ideals of plurality and compromise. Especially when, in terms of real numbers, they’re so outnumbered.

In other words: the call is coming from inside the house. It’s rich old people who hate democracy, not kids who just want to stop getting beat up by the cops. It’s been that way since . . . uhhh . . . how long has democracy been around? Athens?

There Is Nothing After Trompe le Monde

With that said, all we’re left with is the art and stories. Ah!

Richard Case has been almost entirely absent from this essay until now. Most of the running time of this essay has been so far devoted to discussing the Doom Patrol as a franchise and how it relates to Grant Morrison’s career, and handful of moments from throughout the run, and all the themes - so much so that it might be easy to believe, taken out of context, that the Doom Patrol was a prose fiction series.

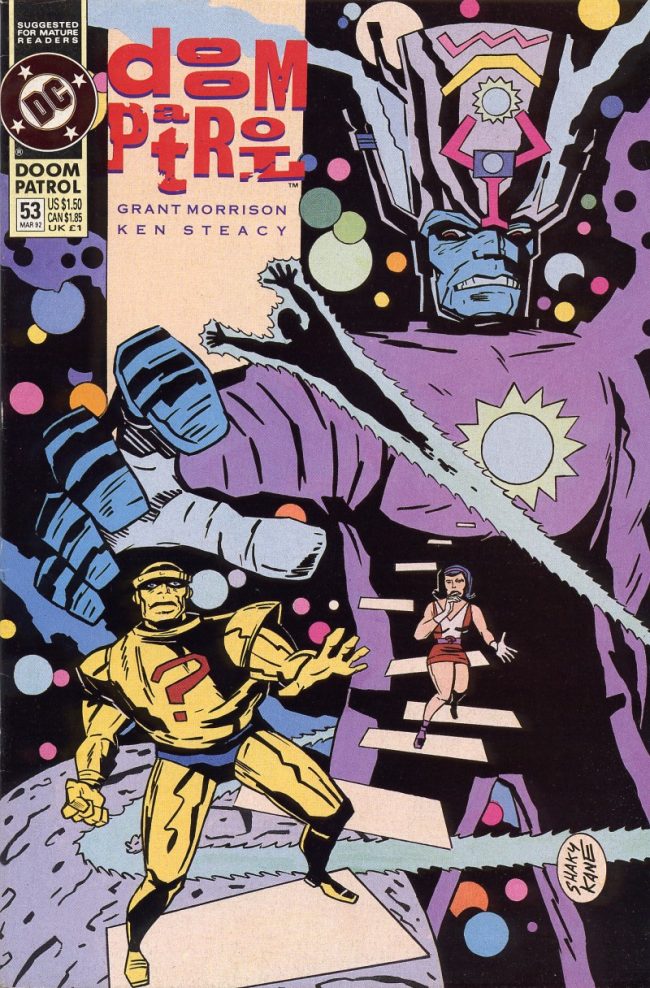

The erasure of the artist seems a significant slight, in the context of a magazine devoted to comic books, which, last I checked, still have pictures in them. It is sadly a common kind of mistake to make. It’s a product that comes from so often referring to the series, and others as well, primarily in relation to Grant Morrison’s career. Grant Morrison wrote a lot of books which were drawn by a lot of people. There have also, it must be noted, been stretches on many of his books drawn by people other than the people who were first supposed to draw them, which I certainly hope is a very polite way of phrasing that particular idea. But this run of Doom Patrol maintains the same level of quality throughout, and while there are artistic fill-ins, they generally remain in the same tone. The art gels really well with the kind of stories Morrison wants to tell. I can’t imagine some of these were very easy ideas to communicate effectively ex nihilo, and yet Case comes through every time.

That the series maintains a consistent and consistently intriguing visual identity throughout the run allows the reader to appreciate just how much that visual identity changes. The book ends looking very much different than when it began, if obviously the product of the same hands. That’s a fun evolution to chart.

Yet it still troubles me that it’s so easy to slide right past the art here. Writers have themes and motifs and trends, and they carry them between different series and stories. If enough of them accrue then you can even indulge in commentary on their careers as careers, as bodies of work that can be compared to each other, and valued for and against one another. Taken as a whole Richard Case’s career would look entirely different. He did a lot of work for Vertigo, with few forays into anything less moody than a Starman special. He actually did a lot of Marvel work - a lot more than I remembered, to be frank, just glancing at his bibliography. Despite the fairly expected run on Doctor Strange he managed to work on some pretty non-Vertigo material, like Cable and a couple years of Sensational Spider-Man. Apparently he works in computer games now, which seems like it was probably a good career move.

I appreciate the fact that this book went out of its way to look so different from the other books on the shelf. The Justice League shows up for a few pages - the Paris sequence - and look like puffed-up mannequins next to the Doom Patrol, drawn nervy and slouching just like real people. It’s a talky book, at times, but the conversations are often memorable, and Case gets a lot of mileage out of body language. The preponderance of talking head sequences is offset by the regular intrusion of the markedly bizarre.

People don’t usually talk about Vertigo and Image in the same breath, because on first blush the two things don’t really seem to have a lot in common. But it’s worth pointing out, Image was primarily born of Marvel’s failure to conduct themselves even remotely fairly or honestly with their employees. The difference is that DC lost Alan Moore in the 80s, and realized after that the best way to keep talent on their good side was to offer them a better deal. And the writers, by and large, seemed OK with the way Vertigo did business. You never heard a lot of talking out of school, and the people who worked there were very loyal. That’s probably down to Karen Berger as much as anything. (It’s also worth mentioning, for the sake of history, that Morrison ended his run on Doom Patrol literally the month before it went over to Vertigo - Rachel Pollack’s run was one of their launch books, but Morrison’s Sebastian O hit stands under Vertigo just a few months later.)

The way you can tell it was a good deal is that they eventually discontinued it. There’s a reason why the DC Universe app is covered in Watchmen crap but will never feature Preacher.

DC was happy at the time to have the reputation, I think, as a place where good writers could settle in and have nice, long runs. Lots of creators were very happy to write for both mainstream DC and Vertigo simultaneously, and the endeavor was often even framed as a productive quid pro quo. Marvel, in hindsight, was relentlessly chaotic and unfocused through this same period - the few decent writers they had at the time were alienated by mismanagement and high-handed editing. The Image rebellion hurt Marvel in so many ways, including by lighting the fuse of the 1993 market collapse, but no less significantly than by broadcasting very loudly that Marvel was a bad place for any ambitious creator to set down roots. The result was a decade of books written by editors - and whether they were in fact the taste often lingered regardless.

That’s not always a bad approach, I hasten to add. The next chapter will be looking at a place where I think it - or something very much like it - works remarkably well.

There is no confusion whatsoever about the fact that this run of Doom Patrol was written by Grant Morrison. It struggles against many of the same problems as other Grant Morrison runs. The villains are often underdeveloped, less antagonists than riddles to be answered (i.e. the Scissormen, Red Jack, the Shadowy Mr. Evans). There’s a bit of Lewis Carroll in Morrison’s more metaphysical moments, in that the shape of the landscape in these stories is often directly correlated to the character’s ability to understand new ideas, and sometimes that works better than others. Perhaps directly correlated to the writer’s sense of humor.

I struggle to remember a time when I ever laughed at a Grant Morrison comic book, if that matters.

There’s a badly-paced outer space interlude right in the middle of the run that nevertheless accomplishes everything a good Claremontian outer-space interlude is supposed to: splits the main cast up for a few months so that they can wring conflict out of the eventual reunion and whatever changes have occurred, and deposits surplus cast members on alien worlds as a way of writing them out of the book indefinitely.

Flex Mentallo was the breakout character in many ways, even though Morrison only ever returned to him once. I like him OK but I thought the Charles Atlas gag was funnier when What The . . ? did it a year or two before. He’s in a TV show, which is not really the weirdest thing to happen in 2020 but is, if we’re being honest, still definitely unlikely. Willoughby Kipling was on that show too!

There’s a bookishness to this run, defined as much as anything by Morrison’s own real-world interests and influences. I’ve always appreciated that about all the classic pre-Vertigo runs, pleasingly literate and wordy in a way often eschewed by later generations of creators and editors but which I regard in hindsight as quite satisfyingly dense. You can’t read an issue of Doom Patrol in five minutes. Even if you aren’t completely satisfied with the whole thing, there’s always at least a morsel or two to chew on.

One of the consequences of writing a more personal book is that there’s a good chance you might put off a portion of the audience who just do not share your interests, even if they might otherwise like many things about the work. I feel like that with Morrison sometimes, with his more personal comics - I find many things enjoyable and even admirable about them, but ultimately I just don’t think I’d enjoy his company very much. That’s a fair assessment, right?

I’ve written a lot of very personal things myself. I imagine there’s people reading this right now who are very happy this essay isn’t quire so dour and introspective, if no less digressive and elliptical. (I mean, come on.) It’s not a bad thing or a good thing, necessarily, that fewer people will show up for the more personal work, but it’s the way things often are.

And, for what it’s worth, I’m almost certain more people will have read these books in the years since they were released, even as the book already sold pretty OK in its day. The run has rarely been out of print, and has often been recompiled into fancy deluxe formats. Every new printing seems to make the writer’s name bigger and bigger, incidentally.

Grant Morrison’s work, at least through the turn of the century, has often concerned itself explicitly with the subject of nostalgia. Interestingly, however, he plays both sides of the fence here. Part of him really likes playing with the old toys. putting them through their paces, and understands that the toys need to be put back carefully if they’re going to retain value. But another part of him recognizes that over-strenuous obeisance to the past can be a very unhealthy tendency, and just wants to smash everything. It’s worth mentioning that much of his career going forward from this point is defined by his generosity as a creator. He’s added quite a bit to Batman, Superman, the JLA, even the X-Men. Actually, pretty much every idea he gave Marvel has been used and reused heavily. Even the Skrull Kill Krew come back now and again, sort of like Team America and US-1 used to. Seven Soldiers and Multiversity were specifically designed to create new ideas and generate new series. Doom Patrol stands out in this context for its hermeticism - it’s not designed to be continued in this incarnation. The next Doom Patrol will always be someone else’s problem.

Grant Morrison’s work, at least through the turn of the century, has often concerned itself explicitly with the subject of nostalgia. Interestingly, however, he plays both sides of the fence here. Part of him really likes playing with the old toys. putting them through their paces, and understands that the toys need to be put back carefully if they’re going to retain value. But another part of him recognizes that over-strenuous obeisance to the past can be a very unhealthy tendency, and just wants to smash everything. It’s worth mentioning that much of his career going forward from this point is defined by his generosity as a creator. He’s added quite a bit to Batman, Superman, the JLA, even the X-Men. Actually, pretty much every idea he gave Marvel has been used and reused heavily. Even the Skrull Kill Krew come back now and again, sort of like Team America and US-1 used to. Seven Soldiers and Multiversity were specifically designed to create new ideas and generate new series. Doom Patrol stands out in this context for its hermeticism - it’s not designed to be continued in this incarnation. The next Doom Patrol will always be someone else’s problem.

Sorry. Thunderiders.

I think I like the one Grant Morrison more than the other, but I think it’s down to the fact that his more personal stuff just doesn’t always agree with me, in a way that really isn’ a slight against the work itself. Perhaps if I had found this run earlier, it could have had more of an influence on me. I read Sandman at a young age (perhaps younger than Sandman should have been read?), and it impressed on me enough that I still go back to it and even defend it, even though I can see in hindsight many places that hold up better than others, and a few downright regrettable passages that I don’t care to revisit at all. As it is, by the time I actually made may way to Doom Patrol I was already kind of set in my ways in regards to Morrison, and preferred his more mainstream work. Doom Patrol is a work that I say, in all affection, should be first read at age 15, not 30.

Still, I do enjoy these comics. I don’t think there are too many of them. The run doesn’t outstay it’s welcome, and ends pretty much when the story feels like it should end. That’s something you can say about Morrison: he usually gets to finish his stories. He usually leaves books in good shape, sales wise. Animal Man sold well enough to stick for years after he left. Even if a few stories might end up compromised for scheduling reasons, and not every side project sells as great as you’d hope, his stories still almost always end up finished.

He arrived at DC during an conservative bump at the company and in this country. Looking at this run in hindsight side by side with, y’know, Millennium and Batman, reveals it a book strikingly out of tune with its fellows, but somehow in a very productive fashion. There’s lots of parodic elements in this run, not just Doom Force. It’s not always a nice comic even if its rarely a mean one. It paved the way for more books like it, and that’s something, even if many of the later books influenced by the tone and structure of this run lacked its wit or earnestness. Morrison is a witty writer, not really a funny one, and I find it easier to appreciate the former than bemoan the latter.

In hindsight there’s a lot of good in Morrison and Case’s run, but there’s some things that can probably stand to be left behind. It was for its time a groundbreaking and transgressive book - in truth, I doubt the sequence with the LSD bicycle would make it at either mainstream company today, in any context, so kudos to that. But as with a lot of books of the period, while it benefits greatly from incorporating more diverse ideas and themes into the story, those same ideas and themes - because they’re real ideas and themes - don’t remain static or unchallenged in the real world. Attitudes change. Queer people and disabled people and people of color and, yes, even women get to write their own stories now. Sometimes.

It’s still conservative, y’know. Think about the list of subjects you probably can’t discuss openly in a DC book now, at any branch of the company. It’s different, certainly, and there’s a lot more diversity, but there are other ways of being conservative than just the Comics Code. Also, many of the more annoying affectations of the late 80s Realpolitik / Corolco Pictures DCU ended up sticking around as permanent fixtures. (Also also because Suicide Squad ended up being one of the most well remembered, and therefore imperfectly duplicated, series of the period. Many of the later books influenced by the tone and structure of that run, however, lacked its wit or earnestness.) I’m sure you can still put in lots of violence, however.

Every incarnation of the Doom Patrol is imperfect. In truth I have more affection for the Doom Patrol as a franchise and concept than I do for Grant Morrison’s run specifically. Something I love about the Doom Patrol is how each version of the book disagrees with the other on very important things. Sometimes the Doom Patrol is really weird and sometimes they play the premise straight, and somehow the ones where they play the premise straight are the weirdest runs of all. The worst runs are those that have tried to convert the idea into house-style superheroes, even if the creators of those runs loved the Silver Age version to distraction. But even in the dissonance there’s something interesting, as if the characters are always haunted in-text by the least interesting versions of themselves.

Kind of like what happens when people change in real life. There’s always going to be someone who thinks you’re just confused, or that its just a phase. Something you’ll grow out of once you start making new friends. They just want you to put on the clothes you used to wear.

Morrison realized the premise could only work if it existed in a process of active self-critique - what kind of ideas and themes are these characters supposed to represent? Don’t be afraid to rip up what has gone before so long as the book’s heart remains in the right place. The idea of such willful, productive destruction sits ill-at-ease with the curatorial nature of fandom. The past is the enemy - as true in the Silver Age, with General Immortus, as with Crazy Jane and her father. Which is one reason why I find the presence of such a strong reactionary streak in Doom Patrol fandom so oddly fascinating: it’s right there in the book that holding onto the past is a great way to get left behind by events.

Nostalgia isn’t all bad, but it is complicated. Animal Man isn’t a book against nostalgia, but it’s about the limits of certain kinds of nostalgia. In the right dose, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with nostalgia as an ingredient in stories - so long as there’s something more than just an appeal to empty nostalgia, an approach that tends to produce a rancid streak of conservatism in fandom as well as life. It’s just another tool a creator can choose to use or not, and can be used well or not. Everybody loves the Justice Society - have you ever heard anyone say, “man, the addition of Jay Garrick really hurt this comic!” Nah, people love those guys, even if it took literally decades of DC being oddly disinterested in publishing their exploits.

There’s a lesson there. Companies don’t like to think about stuff like this, but sometimes when characters go away, and stay away for a really long time, it does help. Not all crops are evergreen. There does not need to always be a Doom Patrol book, any more than there needs to always be a Moon Knight book, or a JSA book. All of these characters have gone long stretches without any use, and have endured periods of outright abuse, but there’s nonetheless no shortage of memorable stories between them.

However - I don’t spend a lot of my day thinking about the JSA, y’know? There’s a time and a place for everything, and when you’re in the mood for that kind of nostalgia Roy Thomas is waiting for you then and there at that time and place.

There aren’t any “good old days” for the Doom Patrol themselves - even the most anodyne versions of the team have still been composed of people absolutely traumatized by life. They go forward, they don’t have a choice in the matter. And they kind of really seriously resent being forced to pretend to be an outdated version of themselves for grandpa.