It is always difficult to define terms, and this remains true for the many forms of graphic narrative. Various forms and different kinds of content make categories provisional, and the way terms are used changes over time. “Webcomics” generally means comics published on a website. But more strictly it refers to comics that are specifically created for and published/released on a computer platform. The term “webcomics” is often used interchangeably with terms such as “digital comics,” “online comics,” and “internet comics” although “digital comics” is sometimes used as an umbrella term that refers to all different digitally produced and distributed forms, including CD-ROM comics and mobile comics. Theorist and creator of webcomics Scott McCloud emphasizes the importance of digital creation—how things change when a creator purposely sets out to create a work for a digital platform—over the effects of digital distribution and circulation. He uses the term “infinite canvas” to characterize the virtually endless page of webcomics (or digital comics) compared to the print page of paper comics (Reinventing Comics 222).

McCloud’s claim about the virtually endless page of the webcomic can be questioned, however, since it does not provide an infinite canvas in practice, despite its conceptual potential. For instance, screen size and shape limit the way in which a creator produces comic panels and also the way the reader accesses them. Despite this, as I discuss in detail below, the webcomic has been constantly evolving, in a process that involves challenging its own limits and inventing not only new artistic forms but new cultural practices, such as different types of distribution and consumption, transmedial creation, and reader-writer interactions. In this article, I examine the differences between print comics and Korean webcomics, or webtoons, and the effects and implications that those differences generate in terms of the aesthetics of webcomics as a new medium, and also discuss the place of Korean webcomics from a comparative perspective. I lay out two general observations. First, “webtoon” is neither an equivalent general term like “webcomics,” nor is it a genre of comics; rather, the webtoon is a complex system created by the distinctive combination of two media (comics and the digital)—one that has brought about a discrete set of interlinked, mutually implicated changes in comics form and aesthetics, production process, and reading practice, and in the concepts and boundaries of authorship and readership, distribution, and consumption of cultural capital. Second, this web graphic narrative, developed in Korea specifically to utilize some of the potential that the digital platform offers, is a new mass media form that links to multiple media technologies and to contemporary mass media.

What is a webtoon, then? A webtoon is a combination of web and cartoon, and was coined in Korea to refer to webcomics. At first, many different terms were used to refer to these digital comics published on websites in Korea. One example is webmic (a compound of “web” and “comics”), which soon lost out to webtoon (a compound of “web” and “cartoon”; Song Yosep 123). In 2000, a Korean web portal managed by Ch’ŏllian had just created a new site for internet comics named “Webtoon.” But most of the comics appearing on this site followed conventional print formats; they continued to use page layouts modeled on printed pages. Webtoon was also briefly used to refer to flash animation, but that meaning soon disappeared (Pak Sŏhwan 128). Before long webtoon became the standard term for comics that are created for and consumed on the internet in Korea.

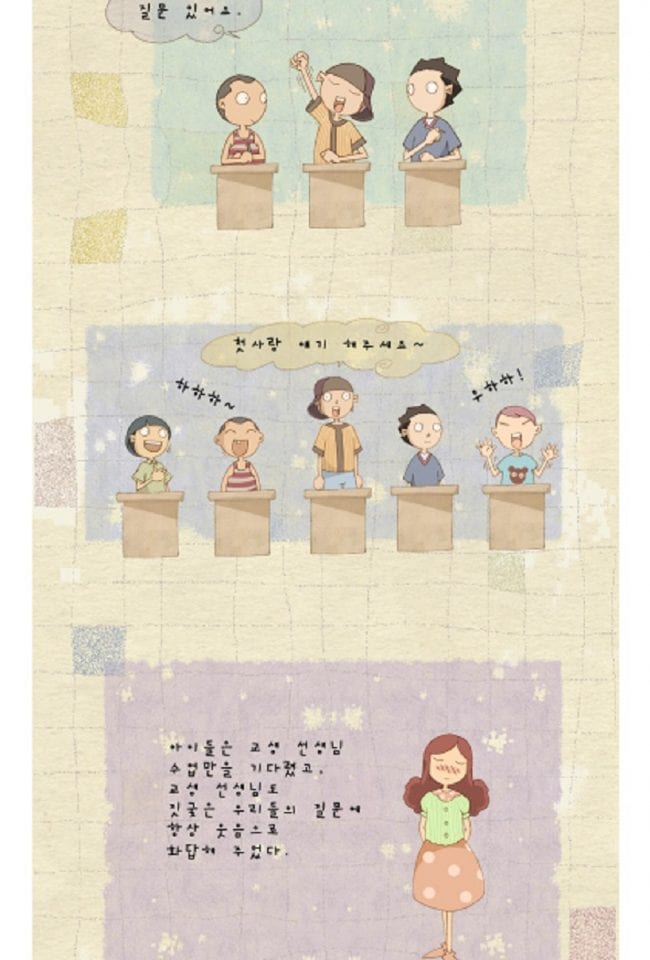

Among many differences between print and web comics, the most significant is the webtoon’s vertical layout. Before vertical-layout webtoons, comics creators who published their works on internet portal sites such as N4 and Comics Today (K’omiksŭ t’udei) in 1999-2000 created horizontal pages that were designed to fit the landscape layout of a computer screen, or that showed one-half of a page of a conventional comics format at a time (Pak Inha 69-70). Once the vertical layout appeared, it was quickly adopted by many artists and now dominates webtoon format. The first Korean webcomic that used this new form was Sim Sŭnghyŏn’s Pape and Popo’s Memories, serialized on a group blog page on Daum, a Korean web portal, in 2002 (Pak Inha 68). It used a vertical layout, and readers could use the scroll wheel on a mouse to read it. The comic that triggered the popularity of this vertical-layout format was Sunjŏng manhwa (A romance comic), created by a well-known webtoon artist, Kang P’ul, and serialized on the Daum portal the following year, 2003 (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/109).

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/109)

The form was then rapidly picked up by other creators and used in webcomics on portal sites such as Daum and Naver, which maintained sections for webcomics on their sites to increase visitor traffic.

Another significant characteristic of the webtoon is its transmediality. Webtoons play a central role within transmedia cultural production while being distributed through multiple platforms and re-created/co-created in this process. Webtoons themselves also become platforms for transmedia tie-ins in which diverse media features converge to create novel aesthetic effects and new cultural genres. Through webtoon’s key aspects of transmedia storytelling and transmedia tie-ins, I examine below the distinctive cultural practices surrounding the webtoon industry in Korea.

The early dominance in Korea of the vertical layout in color is not a phenomenon that took place in other webcomics markets. In Japan, for instance, many webcomics still use a page-like format derived from print and are often in black and white. The situation is similar in the U.S., where either short comic strips or page format for longer comics are popularly used in webcomics. In other words, in Japan and the U.S., as discussed further below, distinctive webcomics forms that would define a new direction of comics culture as a whole have not developed much since moving to digital platforms, although there are some innovative works of individual authors and artists. In these sense, webtoons in Korea appear to have broken away from inheritances from print publication more quickly than have webcomics in other places. After close examination of two distinctive characteristics of webtoons—verticality and transmediality—I therefore discuss the emerging global connections of the webtoon industry. By comparing the Korean webtoon phenomenon with the cases of webcomics in the U.S and Japan, I argue that the webtoon as a new media form is a collective innovation that has both changed overall comics culture and secured its place as a leading popular-culture form in Korea.

Korean comics are noticeably understudied. With the hope that this article can be utilized for (Asian) popular culture courses and (new) media studies courses for undergraduates, I discuss a broad spectrum of webtoon narratives, comparing them with print comics in Korea and webcomics in the U.S and Japan, rather than conducting lengthy analysis of the content of specific comics.

Verticality: Changes in Space, Time, and Directionality

Comics is a medium that interweaves both word and image and thus requires readers to exercise both “visual and verbal interpretive skills” (Eisner 2). It is also a “sequential art” as Will Eisner has defined it, later elaborated by Scott McCloud as being “pictorial and other images [juxtaposed] in deliberate sequence” (Understanding 9). Comics is also a form with specific vocabulary and grammar. Its most fundamental elements are panels (or frames), gutters (the spaces between panels), speech balloons, and text boxes (or captions). How a story is delivered in comics is determined by the way the creator frames a moment in a panel that is itself part of a continuous flow of movement, and also by the way he or she composes the image and text within the frames and arranges those frames sequentially.

One of the most significant differences that the vertical layout creates concerns the role of the gutter spaces. As many comics scholars have argued, the gutter is the space where the reader’s most active participation takes place. It is in this space that the reader actively connects the adjacent panels to construct the narrative flow. For instance, if we see a panel where a man is yawning while watching TV and the next panel shows the same man lying down in bed wearing pajamas, we, the readers, fill in what is missing between the panels: that the man decides to go to bed, turns off the TV, changes into his pajamas, turns off the lights, and lies down. This is what the readers construct to generate meaning or to create movement from still images. In this way, gutter spaces are a unique and generative feature of comics.

Despite their critical role, the gutters in conventional print comics are a visually dull, monotonous space, usually a narrow, white space between panels. But in webtoons, the gutter is used to create a diversified visual space to accompany the text. The gutter sometimes occupies more space than the panels and actively contributes to the narrative in various ways. In some cases, it is used to express the duration of time and/or changes of location by its length. A distinctively long gutter implies a long span of time or major change of scene. In other cases, the gutter uses a background color or design that defines the tone of the whole story. For instance, each episode of Sim Sŭnghyŏn’s Pape Popo uses one long, pastel-toned gutter which embraces all panels within it, and its light-peach or pale-pink color delivers the general impression of the story, which describes a young couple’s sincere and lovely romance (http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/4392).

The vertical juxtaposition of expanded gutters with repeated images of a descending object gives the reader the illusion that the gutters are seamlessly connected, and thus maximizes the effect of verticality that those images have. For instance, the first episode of Ko Yŏnghun’s Changma (Rainy season) uses elongated gutters comprised of thick straight lines—that is, images of strong rain—throughout the first half of the episode (http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/5968).

Figure 3. Ko Yŏnghun, Rainy season (2009-10) (http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/5968)

The rain in these gutters seamlessly connects to other gutters and to the image of rain within the panels, despite the clear division between panels and gutters. The repeated image of rain in dark-colored gutters creates a feeling of fear or anxiety that hangs over the whole episode, in which the scene of a homicide is discovered.

The flexible gutter space in a webtoon also enables its creator to accommodate the text in more various ways. Since the gutter has an expanded space, comics creators often move parts or even all of the text (captions, monologue, dialogue, narration, and words for sound or motion) out of the frame. The relocation of text to the gutter space makes panel space less crowded and lets the reader focus on the images themselves. The separate deployment of texts in the gutter can also deliver different effects in specific contexts. In Kang Toha’s Widaehan K’aetch’ŭbi (Great K’aetch’ŭbi), for instance, the main character’s monologue at the beginning of the episode, explaining that he is unemployed and poor, is placed outside the panels. This external text housed in the gutter visually delivers the sense that the narrator “I” is detached from the character “I,” thus providing the reader with two presentations of the character that are sometimes in tension with one another (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/495).

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/495)

The gutter is no longer simply a break that the reader bridges in her or his imagination. It now becomes a space more substantially involved in narrating the story and more actively used by webtoons creators. It is graphically diversified to deliver specific narrative elements such as the story’s atmosphere, span of time, setting, dialogue, and narration—elements that are supplied only in panels in conventional print comics. As the example of Ko’s Rainy Season shows, the boundary between gutters and panels becomes blurry and penetrable, so that the two spaces are inseparable and complement each other in delivering the story.

Webtoon’s vertical layout not only changes the artistic features and functions surrounding the gutter space but also alters the way the reader/viewer experiences time and space. As Art Spiegelman has commented, comics is a medium that expresses time through space by organizing and arranging sequential moments on the page (Chute and Jagoda 3-4). Time is not an element that is obviously visible in comics, so the organization of space creates temporality of various tempos and segmentations through a number of techniques. For instance, a long panel is considered to indicate or contain a long lapse of time, whereas several extremely narrow panels in sequence express a short, intense period of time, often used for suspenseful or action-packed situations. Thus temporality is instantiated through manipulation of space in comics. This is why Chute argues that “comics is not a form that is experienced in time” (Chute 8). However, comics is also experienced in time; with the inclusion of text—which makes comics distinctive from other visual art forms such as paintings and photographs—comics do express linear, quantifiable time as well as duration, or the experience of time. Yet, it is still undeniable that the expression of time through space is one of the vital features of comics as a medium. This unique temporal-spatial feature of comics becomes diversified in the webcomic.

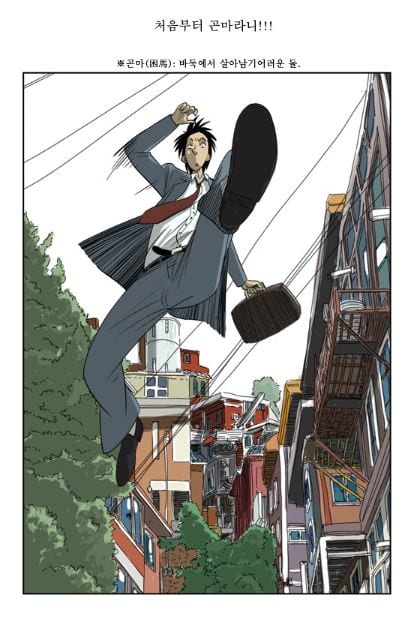

For instance, an extended time-space experienced through an extremely long vertical panel delivers a sensibility of time and space that cannot be expressed in print comics because it would span a number of pages in that format. Episode 53 of Yun T’aeho’s P’ain (A country pumpkin) contains a panel that shows divers who go down to the bottom of the sea to illegally bring up antique ceramics that are believed to have been buried under the sand for several hundred years (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/30249).

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/30249)

This vertical panel is so long (the ratio of width to length is approximately 1:8) that the viewer/reader can see the entire panel only after scrolling down several times on a computer screen. The panel begins with the surface of the water where the divers have just jumped in and continues down to the sea floor where the wreckage of a ship is scattered. As the reader scrolls down the panel, he or she sees only water that becomes darker and darker and seems endless until it finally shows the wreckage of a ship, half-buried in sand, at the bottom of panel. This more realistic representation of the depths of the sea in the webtoon, compared to what is possible in print, effectively lets the reader share the sense of uncertainty and fear that the divers may be feeling.

The unusual panel space also emphasizes the lapse of reading time. While experiencing both the narrated time expressed by the characters’ description of the depth of the sea and the visual representation of the long space of the panel (graphically indicating the time it will take the divers to reach the sea floor in the story), the reader also becomes aware of the passage of reading/viewing time coordinated with the narrated time, precisely because he or she can see the entire panel only by the repeated physical movement of scrolling down. In contrast to regular-sized panels that fit within a screen and do not require additional scrolling, this panel’s extended time-space produces an artistic effect that is similar to camerawork in a film.

The use of vertical layout in the webtoon thus creates diverse expressive effects distinct from print comics. However, the vertical layout also limits the reader’s freedom to wander among panels on the page. In print comics, the reader’s eye can skim from the top left panel of the first page to the bottom right of the second page, and then go back to the first panel to read more attentively, in sequential order; hence the creator has less control over the reader’s eye and there are more diverse ways of constructing the narrative, depending on the reader’s reading habits. In webtoons, the reader’s freedom to wander is restricted. (Japanese Youtube comics “Mangapolo” that automatically play panels control the reading practice even more than webtoons, and films completely control the viewer’s freedom to wander.) Nevertheless, this more regulated directionality of the webtoon is optimal for certain genres, particularly horror and suspense. In the first episode of Kang P’ul’s Iut saram (A neighbor), for instance, the agitated movement of a middle-aged woman’s hands cutting vegetables appears repeatedly without any explanation. She then hears the sound of her apartment door opening and becomes terrified (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/3131).

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/3131)

In the print version of this webtoon, which was published after the success of the web version, the reader can see her dead daughter entering in the next panels on the open page (10-11).

The reader would have trouble avoiding this narrative information when turning the new page, whereas the webtoon reader must scroll down to discover the source of the woman’s reaction. This webtoon style controls the reader’s reading practice and is more effective in the horror genre because webtoons can accumulate tension by controlling the order of panels that the reader sees.

Webcomics are still evolving, and we cannot fully comprehend yet what they will bring in the future and how this will change the history of comics. However, it is quite obvious that various aesthetic changes that generate a different sensibility from that of print comics have already been made, and that in webtoon’s specific case certain styles are being identified as a distinctive—if not optimized—form for webcomics as a new medium. Today the industry of this new mass media form is growing even more quickly than before, due to the service of webtoons on the smart-phone platform: the vertical format of webtoons fits the smart phone’s vertical screen shape perfectly, requiring less frequent scrolling/screen-touching than page-format webcomics.

Transmediality: Transmedia Tie-ins and Storytelling

Because of its web platform, webtoon becomes a site where old and new media collaborate and multiple media functions are combined to create distinctive effects, stories, and genres. The general definition of “transmediality” that Elizabeth Evans provides is useful in explaining the broad range of the practices of cultural production involved in webtoon in Korea. Based on discussions that include Henry Jenkins’s theories, Evans explains, “In essence, the term ‘transmediality’ describes the increasingly popular industrial practice of using multiple media technologies to present information concerning a single fictional world through a range of textual forms” (1). In this section I discuss two different aspects of transmedia production practices within and surrounding webtoons. The first aspect is the transmedia tie-ins that became possible because of the webcomics platform—namely, transmedia narrative that is created within comics by combining multiple media functions rather than a story that is created separately, albeit coordinated and circulated on different platforms. The second aspect is the transmedia production of the narratives on multiple media platforms. Henry Jenkins’s insightful discussion of “transmedia storytelling” through the example of The Matrix phenomenon is helpful in understanding Korean webcomics trends. According to him, transmedia storytelling consists of the narratives that are deployed across diverse media platforms, creating an integrated world with unique involvement from each medium (Jenkins, Chapter Three). However, I would like to expand the scope of discussion of transmedia narrative production here by including traditional ways of utilizing a story to re-create a narrative for different media platforms—such as film adaptations and TV drama parodies of webcomics—which do not always make distinctive contributions to the fictional world-making of the story by revealing the features untold in the urtext.

Unlike print comics, webtoons themselves become platforms for transmedia tie-ins. A simple example is the insertion of background music to enhance the atmosphere and emotion. (For instance, Horang’s Kurŭm ŭi norae [A song of clouds], which depicts members of a music band, includes background songs for some episodes to enhance its storyline. The songs that were played through the webtoon were released as a separate music album afterward. [http://comic.naver.com/webtoon/detail.nhn?titleId=63454&no=7&weekday=mon])

(http://comic.naver.com/webtoon/detail.nhn?titleId=63454&no=7&weekday=mon)

Webtoons also sometimes include short animations in the narrative. In 2009, Yun T’ae-ho published the webtoon SETI, which took full advantage of the layered media potential of the form, creating a new genre called the “Webtoon drama” that inserted a live-action TV drama to a webtoon. Yun designed his characters based on photos of the actors and actresses, and sometimes passed his drawings to the TV producers so that they could develop similar looks for the characters in the TV drama. The two teams worked together throughout the process and inserted a short video clip from the TV series at the end of each episode of the webtoon. This grafting of webtoon and short video clips was one of the advertisement strategies of a camera company (Canon) to demonstrate the capacities of an affordable personal lens versus an expensive professional film camera lens. The digital platform of webtoons also enabled the comics form to explore diverse possibilities, including the use of 3D technology and photographs, for more realistic creation of characters and backgrounds, as well as a sophisticated collection of colors and camerawork-like representations of space and time. This diversified grafting led webtoons to become more readily adapted to films and TV dramas.

Even print versions of webtoons enclose additional features that are enabled by multiple platforms. Until recently, publishing companies mostly published popular webtoons after they had been serialized and tested on portal sites or on personal web blogs. But now that webtoons are established as a new form of comics and there are well-known and popular creators, these creators’ webtoons are often published while they are being serialized on a portal site. In some cases publishing companies even contact a well-known creator, initiate the production of his or her webtoon, and then publish the print version afterward. Most print versions keep the basic format that web version had, except for cutting one long digital page into several print pages to fit it to the print format. But some print-book versions of webtoons also experiment with combining the print and digital forms. For instance, some print books provide access to exclusive video clips using a QR Code (Quick Response Code, or two-dimensional barcode) that readers can view on their cell phone screens; one example is Kang P’ul’s Chomyŏng kage (A lighting shop).

If the reader either photographs or scans the QR Code on a print page with his or her smart phone, he or she can watch scenes of the story (usually about 20-40 seconds long) that are made in an old silent-film style. These video clips, operated by the access to QR Code, instantiate complex transmedia layers of the interactions between the print and digital: in this case, a cinematic feature is accessed through the print version of a webcomic to be played on a mobile phone screen.

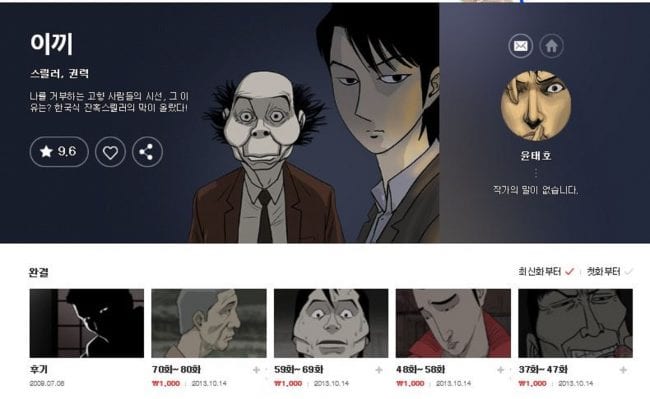

Webtoons are frequently adapted to film, TV dramas, musicals, and theater performances. The most common transmedia production is filmic adaptation. Most of Kang P’ul’s webtoons, such as Sunjŏng manhwa (A romantic comics), Iut saram (A neighbor), Pabo (An idiot), and Ap’at’ŭ (Apartment), were made into movies, while Yun T’ae-ho’s Ikki (Moss) was made into a movie and his Misaeng (Incomplete life) was made into a TV drama (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/view/ikki).

Figure 10. Yun T’ae-ho, Moss (2008-09)

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/view/ikki)

Producers in the film industry often read new webtoons to find potential scenarios and offer the creator a contract even long before the serialization of the webtoon ends. After witnessing the frequent transmedia production of webtoons, consumers of webtoons also anticipate the future circulation of the webtoon narrative on other media platforms. For instance, the readers/viewers of Yun T’aeho’s P’ain, which was serialized on the Daum portal site from July 29, 2014 to August 14, 2015, started to predict the cinematization of this webtoon when less than one-fourth of the episodes had been published. Some readers entertained themselves by making various casting lists and sharing them with other readers through the comments sections that are available at the end of each episode of a webtoon.

Unlike relatively simple transmedia adaptations of webtoons, Yun T’aeho’s Misaeng (Incomplete life), one of the most popular Korean webtoons, provides an example of complex narrative production and distribution through divergent media platforms and genres. (http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/15176)

(http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/15176)

Misaeng, which was serialized on the Daum portal site twice a week from January 2012 through July 2013, describes the life struggles of Chang Kŭrae, a young man who trained to be a professional go player but ends up working at a general trading company as an intern and, later, as a temporary employee. The webtoon shows how this inexperienced young man tries to understand society, people, and his own life. It also shows the entangled and dynamic world of the corporation and its employees, complete with power struggles, corruption, and humanism. Many company workers in Korea sympathized with the content of this webtoon, and it became hugely popular even among the unusual stratum of readers in their forties and fifties, in addition to the usual active readers of webtoons in their teens, twenties, and thirties. As a result, both during and after the serialization of the webtoon many media productions related to the story were created and circulated, including a prequel (online film), an epilogue to Misaeng (webtoon), a TV drama adaptation, Misaeng special episodes (webtoon), and a parody of the TV drama adaptation (TV). Because of the popularity of Misaeng, even the character-product business (including stationery, beverages, paper coffee cups, and socks and tights) was successful, which is unusual when the character is neither a superhero nor a child-targeted character.

What is most interesting in this Misaeng phenomenon is the way that a story is interwoven through the interactions among the multiple media platforms and narrative genres. A few months before the serialization of the webtoon Misaeng ended, Daum Communication, the company that owns the Daum portal site where Misaeng was serialized, made a short film, Misaeng: p’ŭriqwŏl (Incomplete life: prequel). This prequel was released through smart phone apps in May 2013, while the webtoon was still being serialized. As the movie title says, this is a story of the lives of the six main characters of the webtoon before they started working at the trading company. Although the production team of this movie consulted with Yun, the webtoon creator of Misaeng, they created their own story of the characters’ earlier lives that was untold in Yun’s webtoon and thereby enriched the Misaeng narrative, providing the webtoon’s avid readers/viewers with a missing piece of the narrative puzzle.

Soon after the serialization of the webtoon ended in 2013, Yun serialized four more episodes of epilogue from July 23 to August 13, 2013. One of the four explains the production process for the creation of the fictional narrative, which involved the research for real places used as models for fictional settings and interviews with people in the Korean Go Association and trading company employees. The remaining three episodes, however, are a record of Yun’s trip to Jordan. These introduce the reader to a country that appears in one of the most popular episodes during the initial serialization, and that will also be a main setting for Misaeng II, which Yun has promised to create in the near future. (Misaeng II is being currently serialized. Unlike superhero comics in the U.S., most Korean comics do not have sequels. Most Korean comic books and webtoons have been closer to graphic novel forms; they are long usually ranging from two to ten volumes, about two to three hundred pages for each volume, and have extended plot lines. They do not lead to further series based on the main characters and a repetitive narrative structure. Thus the production of the second season of Misaeng is a practice that, though not unprecedented, remains distinctive in Korean comics culture.) Yun’s record of his trip to Jordan also became a basis for the ending of the TV drama adaptation that was broadcast a year later. In this sense, Yun’s epilogues not only connect the fictional and real worlds but also complement the expanding fictional world of Misaeng through a dialogue with other transmedia narratives.

The TV drama Misaeng, which was broadcast a year after the webtoon serialization ended, continued the Misaeng boom in 2014. Although it was adapted by a different TV writer, the drama faithfully followed most of the plot lines and dialogues of the webtoon version, except for the final episode. The ending of this TV drama version, as mentioned above, utilizes the content of Yun’s webtoon epilogues that introduce Jordan as the main setting for Misaeng II and develops a plot line in which the main character starts working with Jordanian trading companies. The TV adaptation thus also serves as a preview of the webtoon Misaeng II.

The Misaeng narrative becomes even more complex by virtue of another layer of five special episodes of webtoon Misaeng, created by Yun and released a day before the first episode of the TV drama adaptation was broadcast. These five episodes are a prequel that describes the past of O Sangsik, the main character’s boss at the trading company, and that provide readers/viewers with an answer to why O’s eyes were colored red from the beginning in the webtoon Misaeng and what they symbolized. Being released a day before the TV show, these webtoon special episodes served as an advertisement for the new TV drama; at the same time, this simultaneous layering gave a transmedia synergy to the promotion of both the TV drama and webtoon stories. In many respects, Misaeng demonstrates not only the fact that webtoon has become a well-established new media form but, more significantly, that webtoon can be rewritten, expanded, and revised by coordinated transmedia narrative productions and thus has grown into an active hub that nurtures multiple media productions.

Collective Innovation: Webtoon Phenomenon in Comparison

Comics is a popular form of cultural production around the world, but generally three major comics-producing cultures have been recognized: the American, the Japanese, and the Franco-Belgian. The popularity of comics in Japan is particularly striking: manga “makes up an estimated 40 percent of the Japanese publishing industry. In comparison, the comics industry in the United States is only 3 percent of the publishing trade” (Duncan and Smith 294). Comics have played a significant role in Japanese culture, particularly in the post-1945 period. The Franco-Belgian culture of comics is notable for the inclusion of the medium as an art: it was a French film scholar who proposed that comics deserved to be considered the “ninth art” in 1964, along with cinema and television (Duncan and Smith 297).

The Korean word for comics, manhwa, derives from Japanese usage and uses the same Chinese characters (漫畫) as “manga.” Before webtoons, Korea had a rather small market for comics, but the development of webtoons has made graphic narrative a thriving industry over the course of just ten years. In 2014 about 17 million Koreans, which is one-third of Korean population, read a webtoon once a month on the Naver web portal, which runs the biggest webtoon site in Korea (Nam Ŭnju n. pag.). If we add in all the webtoon readers who use smaller-scale websites, it would easily be over 20 million.

Responding to the success of the webtoon in Korea over the past decade, the major portal sites carrying webtoons have begun promoting them ambitiously. In 2013 the portal site Naver held its first publishing exhibition of webtoons at the Frankfurt Book Fair to promote Korean webtoons in European countries. In 2012 Daum, another Korean portal site, invested in Tapastic, the first online platform for comics in the North American market, founded by a Korean entrepreneur in the U.S. In 2014 Naver also launched a webcomics site and mobile comics app called LINE Webtoon in the U.S. The LINE webtoon service features a few key elements: free content updated every day, touch scrolling, an assortment of genres, downloading for reading on-the-go, push notification, and a sharing and comments sections (“Popular Mobile” n. pag.). Both Tapastic and LINE Webtoon are exceptional in the U.S. market in that they are open publishing platforms where anyone can publish their webcomics, which is the same system that is used in Korea. They (particularly LINE Webtoon) feature many Korean webtoons translated into English while also embracing webcomics from other, English-language cultures. The site provides American readers with a chance to become familiar with the vertical-layout style and the well-organized full-length narratives of the Korean webtoon.

In the U.S., Scott McCloud, who wrote a comic book about digital comics in 2000, advocates for a shift from a page-based comics form to the more experimental and innovative forms possible in digital comics. In 2009, however, he observes that “most webcomics [in the US] are short gag strips and most long-form comics are page-by-page formats that look a lot like their paper counterparts” (“Webcomics” n. pag.). In 2011, Robert S. Petersen observed the same phenomenon and tried to explain why most webcomics continue to use “comic strip format that fits inside a typical computer screen.” According to Petersen, this is partly because of “technical limitations that made scrolling through long material tedious, but also because readers were often wary of entering into reading a long Web comic when there was no clear end in sight” (Petersen 234). While Petersen was observing that the long vertical or horizontal layout that required scrolling was unsuccessful in America, it was exactly this long vertical format that was enjoying enormous success in Korea. This difference in production/reception in Korea may have been due in part to Korea’s competitive internet speed, but that cannot explain everything. There are American webcomics with vertical-layout formats published on websites such as “theoatmeal.com,” and there are also American comics with vertical layout on Tapastic. In 2012 Marvel Comics launched “Infinite Comics,” which is designed for horizontal, on-screen reading. However, webcomics creators and providers in the U.S. still generally follow the page-by-page format or the comic strip formats.

Japan’s case is similar to that of the U.S., in that Japanese webcomics mostly follow print comics format (page-by-page reading) and use black-and-white images (for instance, Manga Box). In Japan, the print comics market is still strong and influential, although it is shrinking. While portal sites are the main providers of webtoons in Korea, in Japan the existing publishing companies remain the leading content providers of digital comics (Kim Hyowŏn 99). Thus print-book forms are still the main medium that deliver comics, despite the increasing popularity of webcomics.

One of the leading Japanese webcomics sites is “Comico.” Interestingly, this website was modeled on the Korean Naver webtoon site. It employs the details of Korean webtoon style and follows the same management system as Naver webtoon. It features “daily updated content, smart phone capability, comments and active communications, and an open publishing platform” (http://static.comico.jp/about/?_ga=1.241937351.472166869.1426909390), as do Korean portal sites.

(http://static.comico.jp/about/?_ga=1.241937351.472166869.1426909390)

Comico also follows the system that Naver employs to find new comics creators and spread comics culture. Like Naver, Comico has two different open-publishing sections for amateurs, “Challenge League” and “Best Challenge League.” On the Korean Naver site, the most frequently read and highly ranked works in “Challenge League” are upgraded to “Best Challenge League.” If the work is upgraded to “Best Challenge League,” it will have greater chance to be selected for official serialization on the portal site. What is interesting on the Japanese Comico site are the requirements that a work must meet to be upgraded to Best Challenge League: (1) it has to be in color, (2) should be longer than 15 frames, and (3) it must use vertical layout for scrolling (http://www.comico.jp/help/detail.nhn?no=75).

(http://www.comico.jp/help/detail.nhn?no=75)

Rather than popularity and artistic completion, the Korean webtoon form has become the specific requirement for selection on the Japanese site. Comico is therefore promoting the Korean webtoon format as the form it wants to develop for webcomics.

In 2014 Naver, the Korean portal site that launched LINE Webtoon in the U.S., laid out an ambitious plan for webtoons in the global market for the next ten years, declaring that “it will raise the awareness of Korean webtoonists abroad by 2015, expand foreign readership by 2016 or 2017, develop webtoons into a facet of mainstream pop culture by 2018 or 2020, and make webtoons compatible with other mediums by 2024” (Sohn Ji-young n. pag.). This blueprint is ambitious, and it is uncertain how such cultural changes can be measured. However, we see the spread of webtoons taking place in the U.S. and Japan, as well as webtoon’s fast-growing popularity and industry being coordinated with other media productions in Korea. For instance, Tapastic, the American webcomics site partnered with the Korean portal site Daum, is a leading portal that “features more than 1,200 cartoonists and over 24,000 episodes. It recently [in 2014] surpassed DC Comics, famous for comic megahits ‘Superman’ and ‘Batman,’ in traffic rankings by a large margin” (Sohn Ji-young n. pag.).

Hence I would argue that webtoon is not simply a Korean term that refers to comics created and published on a website, thus corresponding to the term “webcomics” in English. Rather, webtoon is also a specific style and system. It is a formal artistic style of webcomics in the sense that it refers to long-form narratives that have been created in an optimized form for web and mobile viewing/reading—a form that features vertical layout, extended panels, and creative use of the gutter space, as well as the use of color, distinctive aesthetics of time and space, regulated directionality, and/or transmedia layers. Webtoon is also a specific system of cultural production/distribution/circulation that features web/mobile platforms, open solicitation, a platform for amateurs, free distribution (though this is changing), profit from advertisements and increasing traffic, active communication between readers and producers, and transmedia productions. The term “webtoon,” for the moment, can therefore be used to refer to the artistic medium that is the combination of this specific style and system, which is to date unique to Korean comics culture but is already expanding to other cultures.

We do not know whether this vertical webtoon form will prove to be the most desirable form for the era of digital comics that is on the horizon—and that has already arrived in Korea, where most consumption of comics is done through webcomics rather than print comics or digital versions of them. However, we can say that webtoon is one form of collective innovation (versus individual innovative webcomic forms, which are not recognized as a major cultural tendency of creating comics on the digital platform). This collective innovation has brought about overall changes in comics cultures in terms of both production and consumption, with the result that webtoon is today a mainstream popular culture form in Korea.

Works Cited

Chute, Hillary and Patrick Jagoda. “Introduction.” Special Issue: Comics & Media. Critical Inquiry 40.3 (March 2014): 1-10. Print.

Chute, Hillary. Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010. Print.

Comico. Web. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://static.comico.jp/about/?_ga=1.241937351.472166869.1426909390> and <http://www.comico.jp/help/detail.nhn?no=75>

Duncan, Randy and Matthew J. Smith, eds. The Power of Comics: History, Form, & Culture. London: Bloomsbury, 2009. Print.

Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and Practices from the Legendary Cartoonist. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. Print.

Evans, Elizabeth. Transmedia Television: Audiences, New Media, and Daily Life. New York: Routledge, 2011. Print.

Horang. Kurŭm ŭi norae (A song of clouds). Episode 1. 18 May 2009. Web. 27 Mar. 2015.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006. Print.

Kang, P’ul. Chomyŏng kage (A lighting shop). Seoul: Ungjin Ssingk’ŭbik, 2011. Print.

———. Iut saram (A neighbor). Seoul: Chaemijuŭi, 2012. Print.

———. Iut saram (A neighbor). 2008. Web. 22. Jul. 2015. <http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/view/neighbor>

Kang, Toha. Widaehan K’aetch’ŭbi (Great K’aetch’ŭbi). Episode 1-1. 2 Mar. 2005. Web. 22. Jul. 2015. <http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/495>

Kim, Yowŏn. “Ilbon dijit’al manhwa k’ont’ench’ŭ ŭi chuyo saŏpcha e kwanhan yŏn’gu” (A study on main business of Japanese digial comics), Aenimeisyŏn yŏn’gu 10.4 (December 2014): 90-112. Print.

Ko, Yŏnghun. Changma (Rainy season). Episode 1. 26 Oct. 2009. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/5968>

Manga Box. Web. 25 Mar. 2015 <https://www.mangabox.me/>

McCloud, Scott. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology are Revolutionizing an Art Form. New York: Perennial, 2010. Print.

———. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial, 1993. Print.

———. “Webcomics.” February 2009. Web. Mar. 26, 2015. <http://scottmccloud.com/1-webcomics/index.html>

Nam, Ŭnju. “Wept’un chŏnjaeng” (Webtoon war). 21 Apr. 2014. Web. 22 Jul. 2015. <http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/culture_general/633871.html?_fr=mb3>

Pak Inha. “Han’guk dijit’al manhwa ŭi yŏksa wa palchŏn panghyangsŏng yŏn’gu” (A study on the history of Korean digital comics and its future directions). Aenimeisyŏn yŏn’gu 7.2 (June 2011): 64-82. Print.

Pak Sŏkhwan. “Wept’un sanŏp ŭi silt’ae wa munjechŏm” (The actual condition of webtoon and its problems). Dijit’al k’ont’ench’ŭ wa munhwa chŏngch’aek 4 (2009): 123-158. Print.

Petersen, Robert S. Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2011. Print.

“Popular Mobile Webcomic Service, LINE Webtoon, Debuts in the United States and Worldwide.” 2 Jul. 2014. Web. 26 Mar. 2015. <http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/popular-mobile-webcomic-service-line-webtoon-debuts-in-the-united-states-and-worldwide-265512371.html>

Sim, Sŭnghyŏn. P’ap’e p’op’o (Pape Popo). Episode 1. 6 Apr. 2009. Web. 21. Jul. 2015. <http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/4392>

Sohn, Ji-young “Korean webtoons going global.” Korean Herald. 25 May 2014. Web. 26 Mar. 2015. <http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20140525000452>

Song Yosep. “Wept’un ŭi palsaeng kwajŏng t’amsaek kwa paljŏn ŭl wihan cheŏn” (A study on the formation of webtoon and suggestions for its development). Han’guk chŏngbo kisul hakhoeji, Vol. 10, no. 4 (December 2012): 133-137. Print.

Yun, T’aeho. Misaeng (Incomplete life). 20 Jan. 2012 – 19 Jul. 2013. Web. 22 Jul. 2015. <http://cartoon.media.daum.net/webtoon/view/miseng>

———. P’ain (A country pumpkin). Episode 53. 14 Apr. 2015. Web. 22 Jul. 2015. <http://webtoon.daum.net/webtoon/viewer/30249>