Julie Doucet has been a role model for two generations of cartoonists. She gained notoriety with her early 90s Drawn and Quarterly comic book series Dirty Plotte, containing strips like “Heavy Flow,” in which Julie grows to Godzilla proportions while having her period, and she plunges her hand into a drugstore, looking for tampons. After a string of books, including the seminal My New York Diary (1999), Julie quit comics, turning to hybrid forms. Her new book for Drawn & Quarterly, Carpet Sweeper Tales, uses collaged Italian fumetti (photo comics) to tell Dada-esque vignettes. I spoke with Julie by phone about found materials, quitting drawing, and flirting in cars.

Julie Doucet has been a role model for two generations of cartoonists. She gained notoriety with her early 90s Drawn and Quarterly comic book series Dirty Plotte, containing strips like “Heavy Flow,” in which Julie grows to Godzilla proportions while having her period, and she plunges her hand into a drugstore, looking for tampons. After a string of books, including the seminal My New York Diary (1999), Julie quit comics, turning to hybrid forms. Her new book for Drawn & Quarterly, Carpet Sweeper Tales, uses collaged Italian fumetti (photo comics) to tell Dada-esque vignettes. I spoke with Julie by phone about found materials, quitting drawing, and flirting in cars.

Interview conducted by Annie Mok, transcribed by Aaron King, and edited by A.M. and Julie Doucet.

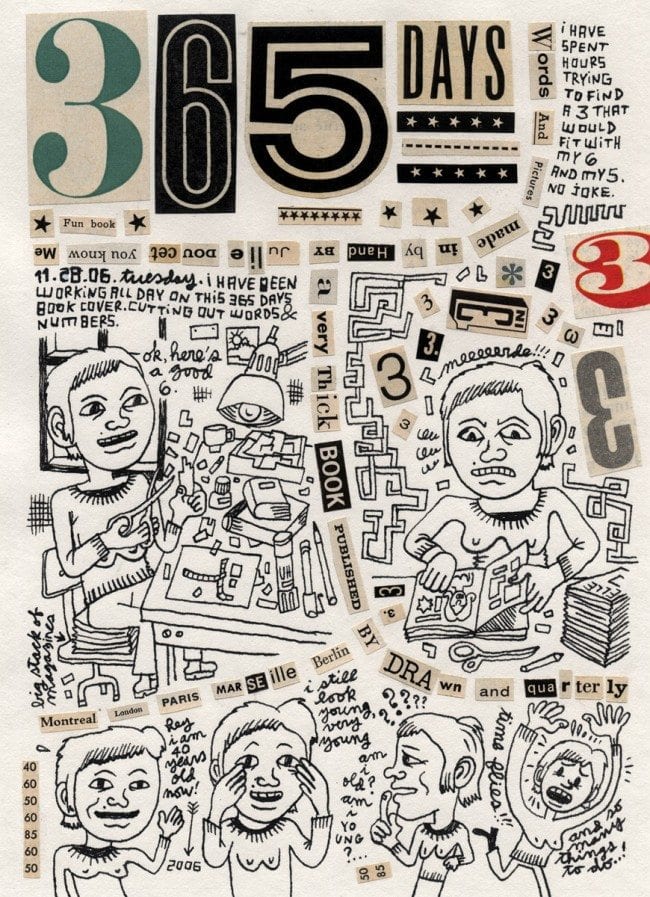

ANNIE MOK: First thing I noticed about your new book, Carpet Sweeper Tales, is this interesting trajectory that has happened over the course of your career, from stuff like “Heavy Flow” to My New York Diary, where you’re working really with your own drawings… and then there was this point where you officially quit comics and started bringing in more collage elements [along with drawings] in books like 365 Days. And then in Carpet Sweeper Tales, you have exclusively collage elements from these Italian fumetti magazines from the ‘50s through the ‘70s, mostly in the ‘60s. What do you get from working with collage elements and found materials that you may not get from drawing, right now at least?

DOUCET: Yeah. I guess I have this—I did this movie with Michel Gondry? That involved drawing, and at this point in my life, I wasn’t really into it, but because it was Michel Gondry, I figured, oh my god, yeah, I want to work with him. It was supposed to be a very short project or even just a test, but it ended up being quite a big deal. I had to make about 80 and some more drawings, but I couldn’t make it. At one point, I just broke down and—how do you say that?— burnout. I got mononucleosis, and since then, I had a mental block. I just couldn’t draw anymore, not at all. I was already into making collages, so I ended up doing only collages from then on. And I did quite a lot of different projects with that. It’s just that it was mostly in French, so I guess most of Anglo, English-speaking people didn’t see any of it. I did lots of poetry. I wrote my autobiography to 15 years old. It’s 200 pages.

MOK: Oh my gosh. Is that out in any form yet, or is that yet to be seen?

DOUCET: Yeah, it was published by Le Seuil in France, but it looks more like a—you know, it’s poem form, so it’s not like a full page of text, so it’s not that bad. And next, with the leftover words from that project—because I always keep the words and syllables in cardboard trays—so from then on, I started to create words, and I made up a new language with the cutout words. I made a dictionary with them. So the Carpet Sweeper Tales was just the following step.

MOK: And so speaking of making up a new language, Carpet Sweeper Tales has what seems like scat-inflected—I’m reading page 28. This nun says, “Because Be Ba naly ap hoa wa wo ca coo spinc ra ori coa be ney,” and then the other woman says, “Bo?” [Doucet laughs. And you say at the beginning of the book, “Read it out loud,” which I loved. I love things with instructions. It reminded me of Ziggy Stardust or the Cure’s Disintegration, albums that would say to play it out loud in the liner notes—or things like [the influential art group] Fluxus or Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit—things that have instructions to the reader. And it brings this performative element into it. What was it like making this new language and developing this vocabulary?

MOK: And so speaking of making up a new language, Carpet Sweeper Tales has what seems like scat-inflected—I’m reading page 28. This nun says, “Because Be Ba naly ap hoa wa wo ca coo spinc ra ori coa be ney,” and then the other woman says, “Bo?” [Doucet laughs. And you say at the beginning of the book, “Read it out loud,” which I loved. I love things with instructions. It reminded me of Ziggy Stardust or the Cure’s Disintegration, albums that would say to play it out loud in the liner notes—or things like [the influential art group] Fluxus or Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit—things that have instructions to the reader. And it brings this performative element into it. What was it like making this new language and developing this vocabulary?

DOUCET: I guess it was half-visual and half-sound. It kind of had to look good on paper and sound good, and sound… it couldn’t be too close to an actual, real word, or if it was kind of close, it had to mean something completely different.

MOK: So you wanted to instill a sense of layers—that what the words were didn’t reflect exactly what was going on in the text. Is that what you mean?

DOUCET: In the sense that there was no way to guess what the word was.

MOK: Oh, I see. What the origination is.

DOUCET: Yeah, but the dictionary—the new language that I created—has nothing to do with the words that are in Carpet Sweeper Tales.

MOK: I meant just a new language in general, I guess. So major themes of the book are masculinity, toxic masculinity, and cars? [Doucet laughs.] And it’s so interesting—you’re taking these images from these ‘60s Italian fumetti, which are this incredibly butch series of scenes, some of them very threatening men—like, threatening to women, and women in compromised positions, and then there’s this constant iteration of cars and men speaking of women as if they are cars in some cases, or alluding to them that way. And talking about, like, where someone can take you, and what is freedom. How did this playful thing around cars develop, and what does that mean to you?

DOUCET: In those fumettis, for some reason, there’s lots and lots and lots of action going on in cars—a lot of conversations. And I talked to my aunts, my older aunts, and they told me that was just the way it was at the time, because people didn’t really have any places to go to flirt or anything like that, so pretty much everything happened in cars. So in that sense, it makes sense in that context. But I just loved the car thing, so I just cut out everything I could find going on in the cars.

MOK: What was your initial draw to fumetti—to this material—as opposed to another source for images?

MOK: What was your initial draw to fumetti—to this material—as opposed to another source for images?

DOUCET: I found some fumettis in a garage sale, and I kind of like the look of it. It’s very cheaply made, and I tried to make other projects with that, more comics-form-like—full pages with many panels—but I never could get around with it. The project originated more from the text, really. I wanted to make text with made up onomatope like words more than anything else, but I figured that it was maybe a little too hard to take, so I decided to add the pictures. I ended up cutting up the pictures I liked in the fumetti and create my own narrative out of it. And then wrote the text. Of course you have a precise idea of what you want to do when you start, but then it drifts along the way. It ended up not being 100% sound-like text but a mixture of it with existing words. And the way I work with the cutout words is that I start with the leftovers from the project before. I pick one word, and I try to build something around it. It’s the starting point. It doesn’t look like it, but it is quite a lot of work.

MOK: Yeah, I certainly imagine so. So the fumetti, as you point out, is very cheap. There’s this intense concern with glamor. All the women are of course very made-up, I guess this would be Italian neorealist era, I think of [the Fellini film] 8 ½ and that kind of stuff. To me, it hearkens back to Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Dada artists like Hannah Höch and then punk artists like Linder Sterling because you’re playing with this kind of distanced imagery where the actors in the photos are really not into it. In a lot of cases, they aren’t even looking at each other. And then there’s all these conversations about power. But then you’re also subverting it, ‘cause as you say, there’s this focus on pure sound. So I guess I’m curious about what the inspiration for pure sound—for words that were pure sound—were originally, and then also, what was it like creating this interplay between these strange, stark narratives and then keeping the focus on vowels and consonants and the sounds that words are making.

DOUCET: My inspiration for the text is more a French-Canadian writer—Claude Gauvreau,his name is—so hedid a lot of that kind of stuff, meaning writing poetry with made words. Lettriste poetry, a thing the Situationists [in France] did.. He would read his poems out loud in performances in poetry.

MOK: So I’m curious about working with these images that are so stark and all about power and are also really kind of funny and campy in a way that the actors look bored, or they’re not looking at each other when they’re speaking to one another. And also what the contrast was like working with this playful text at the same time.

DOUCET: Yeah. Well, I guess it was not really planned. You know, I like the look of it, and you just can’t find that kind of material at all anymore. And also, there is the copyright. These were so obscure, I was sure I could use them. But yeah, I picked that visual, and I like the aesthetic of it. Contrasts work very well, in general, it’s a good trick, always funny results.

MOK: The title, Carpet Sweeper Tales—again, this seems like one of those very intuitive decisions, but I’m curious if a carpet sweeper has a particular meaning to you or if it was more about the Dada “putting incongruous things together” thing.

MOK: The title, Carpet Sweeper Tales—again, this seems like one of those very intuitive decisions, but I’m curious if a carpet sweeper has a particular meaning to you or if it was more about the Dada “putting incongruous things together” thing.

DOUCET: “Carpet sweeper” is part of a dialogue in the book. I just needed something, a word or group of words to refer to the book… I’m not very good at finding good titles, that was the best way for me to make it work out.

MOK: I feel like your works often teach the reader to read them in the way I think of a lot of comics, like Chris Ware and other works. I’m curious if there are works that feel like that to you. You mentioned this poet who was doing performance work—this French-Canadian poet—or just other works that take the reader on a journey in the way that this book does and in the way that some of your other books do, working with reader expectations and playing with forms. Are there works that you were looking at that were inspiring you in that way?

DOUCET: I usually try to not look at other people’s work, at least work similar to what i’m working on. Inspiration… I tend to keep to myself, to stay in my bubble, to try to not get distracted, not contaminated...

MOK: [laughs] That’s fine.

DOUCET: So I’m not sure I can talk about inspiration, but about art that I appreciate and that amazes me, yes.You know this small Canadian publisher, Conundrum Press? They translated a book from a Chinese artist [Chihoi], The Library. That is quite an amazing book. He has a way to draw pictures from completely different points of view, in a way you don’t see too often. Very cinematographic. And also, I really like this woman from Finland. She has a bit of a complicated name. She had a book published by Drawn & Quarterly.

MOK: Oh, are you talking about maybe Amanda Vähämäki?

DOUCET: Exactly. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I really liked her book. Beautiful drawings and for once, it was not autobiographical.

MOK: Uh-huh [laughs].

DOUCET: Of course yes I’ve done plenty of it, but I think autobiography—it’s sort of a mental illness. [Mok laughs.] Yeah, in a way! You can do it for a while, but you have to move on to something else, unless you’re somebody like [King-Cat cartoonist] John Porcellino, who has a very special and personal vision about how to do it.

MOK:So was the memoir format a big part of you deciding to quit comics when you did? Was that a drain on you, specifically doing autobiographical works?

DOUCET: Um, no, because when I officially decided to quit comics, afterwards, maybe three years later, I did this book, 365 Days, which was, you know, one page a day for a year. It was completely improvised, but it was so far for me—from the way I used to draw comics—that it was a totally new experience to me. It had nothing to do with me wanting to stop drawing comics. I just felt trapped, needed to try other things, other forms of art. At the time, when I showed that project to my publishers (the original is in French so i showed it to my French publisher first, then D&Q) to them that was not quite comics. It is, of course, but it was not viewed that way then. Things have changed quite a lot in the comics world in the past 12-13 years.

MOK: I love this story at the end of the book where this woman enters—is found dying on train tracks, and she meets this man, and he says that he’s Pyrex. “I am the caretaker here,” and it’s the Garden of Death, and this place is a crossing point. And it was also interesting to see, like you were talking about, this progression where the bulk of the book is centered around these sound-centric words, and then at the end, you get this very narrative-centric piece right before the epilogue, which, again, is more sound-centric. Can you talk about this piece, “Bang Clock Cold,” where this woman enters the Garden of Death? I love things about thresholds, and I love things about dying and ideas about dying.

DOUCET: The materials from that fumetti magazine were just amazing. I guess I had to find a way to make a build-up throughout the book. Each story being in the most part improvised i cannot talk about any real intentions. I was looking for a sort of momentum - i guess that would be the word. I had this idea of a character who could speak normally...It took me a while, but I finally found a way to include it. It works nicely. I don’t really have a great explanation for it.

MOK: But that makes a lot of sense to me—the idea of a book having dynamics and having this push/pull throughout it, and you feeling like you needed something at the end is interesting. So much of the book, like I said, is about—and, I mean, not a surprise if anybody’s familiar with Fellini movies coming from the same period—the book is a lot about shitty men in suits, and it’s interesting—I was thinking of so many of what we think of as seminal graphic novels by women being—Ulli Lust’s work, MariNaomi’s work—are about shitty men. I guess I don’t have a question about that, necessarily, but it certainly comes up in your work a lot, in My New York Diary and other stuff. I’m curious about—what was your approach to—and I don’t know it was planned, and it seems like it was really largely coming off the material to you, and largely intuitive, but what your thoughts were about masculinity and working with these themes of toxic masculinity in the book. What do you see in the book coming out of it?

DOUCET: [Laughs] I have no problem with masculinity. [Mok laughs] And you always tell stories where things go bad, right?

MOK: Well, I’m not saying masculinity as a whole. I’m just saying when it’s shitty—when it’s toxic.

DOUCET: Yeah. Well, of course the material was calling for something like that.

MOK: That makes a lot of sense.

DOUCET: And because of the epoch of it. I hope I wasn’t too hard on men in that book.

MOK: I don’t think it’s too possible to be too hard on men. I wouldn’t worry [laughs].

DOUCET: No, no, but I didn’t want to be hard.

MOK: Oh, I know what you mean. I mean, even though it is about that, it’s also so playful in its form. I don’t think it comes off as too harsh at all. I’m curious if there’s anything—I don’t want to keep you too long—I’m curious if there’s anything in particular you’re interested in next. Seeing this trajectory from your books, it makes me really curious as to what you feel you might be moving onto next.

DOUCET: Yeah, surprisingly enough, I’m going back to drawing now.

MOK: Oh, okay, interesting.

DOUCET: The mental block is over. What happened is, you know the killing in France of Charlie Hebdo? I have met over the years, two or three of those people—they were late at the meeting, so nothing happened to them—and all of them are, were friends of friends of mine… Also, I grew up with newspapers like Hara-Kiri and later, Charlie Hebdo, they were big influences, especially as a kid, for that kind of a humor. So it really hit hard. It’s not like it made me angry. I was stunned. It made me terribly sad. And, the next day, I started to draw again, it made sense again.

MOK: Wow.

DOUCET: Yeah. Drawing and pictures, especially drawing, didn’t seem to make sense to me anymore, because there are too much of it too many images. And, you know, it seemed to me that they were emptied of their meaning, that they had become useless. but all of a sudden, it seemed to make sense again. So, because i could, at last, I decided to start drawing again, but to start from the beginning, to go back to the basics. I borrowed some anatomy books, tried to teach myself to draw a different way, to break my hand drawing, my habits. Try to go somewhere else.

MOK: Interesting.

DOUCET: So I’m just drawing and drawing and experimenting at the moment. I have no idea where I’m going with that—if it’s ever going to be narrative or not. I’m really enjoying it now.

MOK: I am sorry to hear, of course, about the friends of friends, and that sounds like a really difficult thing to go through, but I am glad to hear that you’re drawing again. What was the benefit to you—I know you’ve said it in other words, but I’m just curious to hear you talk about the benefits of quitting comics and what you got out of quitting comics and of saying you were quitting comics. What that maybe brought to your life.

DOUCET: One of the reasons I quit is—I had to work all the time on comics to make a living. So you end up working all the time, all the time, all the time. Quitting comics was a big relief in that way. I could concentrate on other things. Tried all sorts of different things. And for some time i was still getting royalties from the comics and the money was really good for a long time. [Mok laughs.] So that really helped. I could, you know, just do whatever I wanted for a while. And also, in Canada, you can ask for art grants, which is a big help.

MOK: So you live in Montreal, of course, and you mention Canadian places a couple times within the context of the book. What is meaningful to you, I guess—is there an artistic community? Or are there things you get from Montreal? Of course your publisher, Drawn & Quarterly is there, and you’ve been there kind of a long time, as far as I know, so I’m curious what it’s like for you living there, and what does it do for your practice to be there?

DOUCET: The main thing is that it’s a very cheap city, and it’s probably the one place in the world where I could afford to have a studio. I don’t even have a studio of my own—a community studio, a printing studio. You can pay only the month you’re using it, so it’s very convenient and not expensive. My rent at home isn’t very expensive either, so I can get away with not making much money. when I came back from Berlin—the one reason I left Montreal in the first place was that I thought that, people were just too comfortable here, in some ways, I felt that it was not really a vibrant environment for making art, you know, but after a few years of being back, I did end up meeting people that had a good drive creation-wise, so I feel I’m at the right place, now.

MOK: Mm-hm. I don’t want to keep you, but thank you so much, Julie. I really appreciate it. It was really great to talk to you.

DOUCET: Yeah? I would just like to mention, Fantagraphics published The Complete Wimmen’s Comix? They sent it to me, I just wanted to thank them. It’s very interesting to see, you know, where it all started in America, and the evolution of it and then makes you realize how much the society and all changed for the best. It’s not perfect, but we come from a long way, right? You can feel and see in the first issues that the women, some of them weren’t really used to drawing, the urgency of expressing themselves, had so many things to say, you know?

MOK: Are there particular artists in that collection that you’re responding to? Like Diane Noomin or Aline Kominsky or anyone’s work in particular that you were really struck by?

DOUCET: Lee Binswanger. It’s very, very simple line drawings but quite beautiful, and her humor and stories are slightly absurd. I really love them. I think back in the ‘90s, I wouldn’t have really appreciated them, but now she’s really my favorite.