What was it like making webcomics in the distant dawn times of the year 2000? For me, it was all about editing artwork on MS Paint and being home at 9:00 every night so I could upload the next day’s strip by midnight EST. In other words, ridiculous.

I’ve been around long enough in Internet time to count as a grande dame, and to prove it I recently sat on an old-webcartoonists panel, kindly entitled “Masters of Webcomics,” at the Silicon Valley Comic-Con in San Jose. Moderator Chuck Whelon (Pewfell), cohost of the podcast Masters of Webcomics and himself a longtime webcartoonist, oversaw Jonathan Lemon (Rabbits Against Magic), Jason Thompson (The Stiff), Jason Shiga (Demon), and myself, as well as surprise mystery guest Andy Weir, who started his creative career with the webcomic Casey and Andy before writing The Martian. Whelon’s cohost, Adam Prosser, checked in from Toronto via a spotty Skype connection. Cartoonist Amber Greenlee (No Stereotypes) sadly had to cancel at the last minute.

Weir’s appearance was the worst-kept secret in San Jose, and the audience began applauding as soon as he walked onstage in a face-concealing space helmet. When, at Whelon’s direction, he slowly removed it to the strains of Also sprach Zarathustra, another round of applause broke out. The ostensible subject of the panel was “How can making a webcomic form the foundation of a career in the creative arts?” and there was no doubt which of the panelists had managed it most spectacularly.

But none of us had started with the idea of building a career. Except for Shiga, who was late to the Internet, everyone got into webcomics around the early 2000s, and we all agreed we had no idea what the Web was going to be. “There wasn’t any plan,” said Lemon, who decided to try cartooning after a stint in the Peace Corps. “I deliberately started drawing with absolutely no plan, no characters. The idea was to see what developed and what I liked doing.”

Lemon stuck to a four-panel strip format in case he got the chance to sell Rabbits Against Magic to a newspaper syndicate. It did get picked up by a syndicate, but not for print; it now runs on GoComics.com, the online presence of Universal Press Syndicate/Uclick.

Rabbits Against Magic strip from 2008." width="600" height="217" class="size-full wp-image-92049" /> A Rabbits Against Magic strip from 2008.

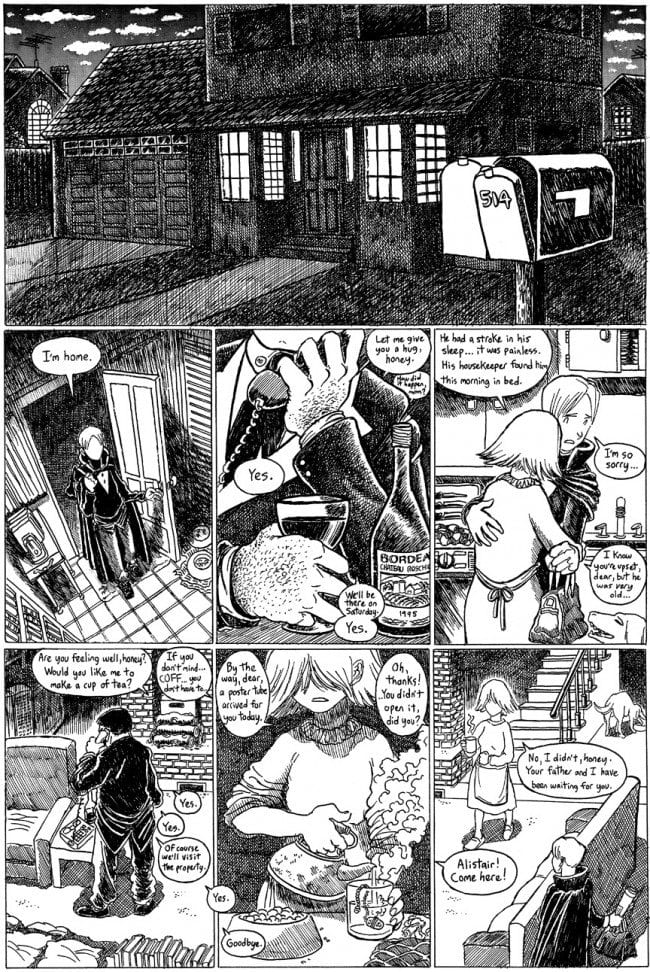

Rabbits Against Magic strip from 2008." width="600" height="217" class="size-full wp-image-92049" /> A Rabbits Against Magic strip from 2008.Thompson, a former manga editor at Viz Media, was fascinated by long-running manga and wanted to do “a super-detailed manga-style long-running webcomic.” He was already an indie cartoonist with self-published comics under his belt. But in the 2000s his artistic career took a back seat to his editorial work at Viz, especially after he was placed in charge of the new Shonen Jump magazine.

Then Thompson reached his Damascus at an editorial meeting in Tokyo: “I was in Japan talking to one of the Japanese editors of Shonen Jump; this was in 2002. He said, ‘Tell me, did you ever want to do comics when you were a boy?’ And I was like, ‘Wait a minute! I still want to do comics!’”

After launching The Stiff on the Modern Tales spinoff site Girlamatic.com, Thompson churned out pages like a man possessed, but he started taking hiatuses to plan and storyboard. “Looking back,” he says, “I think it would have been better if I’d had a continual streak, even if I was driving blind.” The Stiff is still uncompleted, but it allowed Thompson to relaunch his art career. Today his bread and butter is in illustration work for Dungeons & Dragons; he also draws comics and writes graphic novels.

Thompson wasn’t the only panelist to do time on Modern Tales, one of the early hubs of webcomics culture. I drew or wrote comics for almost every Modern Tales site, and Whelon was one of the MT launch artists, as was the unfortunately absent Greenlee. (Ethics in webcomics journalism alert: a number of the panelists were friends from way back. Webcomics used to be a cozy world.) Whelon took a moment to pour one out for the late Joey Manley, founder of Modern Tales: “If you’re a fan of comics, you don’t just have to be drawing them. You can be supporting artists and getting them going.”

Weir, meanwhile, got into webcomics as an admirer of Bob the Angry Flower creator Stephen Notley, one of the earliest free-weekly cartoonists to start posting his work online. “This guy just makes comics and puts them online,” Weir remembered thinking. “That’s pretty cool.” Weir’s strip Casey and Andy, launched in 2002, attracted a devoted audience with its mix of goofiness and brainy sci-fi humor.

For his second comic, Weir planned a full-length graphic novel, Cheshire Crossing, that updated one monthly “issue” at a time. His literary ambitions started to run up against his limitations as an artist. The now-defunct blog Your Webcomic Is Bad and You Should Feel Bad attacked it viciously. But “even that scathing review said the writing was good, just that the art was crap,” said Weir. “I can accept that.”

Crucially, Weir’s webcomics provided him with a mailing list of readers for his prose fiction. “Those core Casey and Andy readers are the ones who became the readers of The Martian when I was posting it chapter by chapter,” he said. “Which is why The Martian is so technically accurate, because my core readers were a bunch of hardcore nerds.” By the time The Martian finished serialization online, it had a massive audience that swept the print version of the book onto bestseller lists.

Before Kickstarter, IndieGoGo, Patreon, and modern social media, there was no clear path to building an online audience or making money. Webcartoonists today have more resources but navigate a more complex, competitive field. Shiga, a longtime indie cartoonist and graphic novelist, entered that field just two years ago. Although he’d already been reposting his print comics online (including an elegant interactive version of his choose-your-own-adventure graphic novel Meanwhile), Shiga’s first comic to debut on the Web was his most recent: the massive, indescribable Demon.

(Shiga attempting to describe the indescribable: “It’s about this guy who discovers he can’t die, and he goes on to perform various experiments to figure out why this is… Andy, you might like this. At one point, he’s stuck in a jail cell with no way to escape. There’s nothing in this jail cell except a square of toilet paper that got stuck between his balls and his anus. And using only this one piece of paper, he has to escape from the jail… Oh, wait. There’s kids here.”)

Shiga submitted a complete penciled draft of Demon to his publisher, Abrams Books. “Basically, my agent and my editor got me on a three-way phone call and begged me not to do this project.” With no publisher willing to touch Demon (see above re: toilet paper, balls, anus), he serialized it online, picking up subscribers through Patreon. By the time it ended, it had found an audience—and a publisher, First Second, which will produce the print version of Shiga’s 712-page epic.

Some of the panelists still publish comics online, others don’t, but all spoke highly of their webcartooning days. “A webcomic allows me to do whatever I want to do,” said Lemon. “I’m my own boss, no one can tell me how to change it. That’s very important to me as a creative person.”

The two Jasons appreciated the space to tell longer stories and develop characters. “Unfortunately,” said Shiga, “it’s really hard to do that in the span of a 2- or even 300-page graphic novel.”

Above all, everyone liked being able to build a close connection with readers. As Lemon put it, “I spend an enormous amount of my time locked in my hermit-like basement like a mole rat, so it’s good to get feedback.”

“All forms of artists, whether it be narrative fiction or art or acting or anything else, really want to know that there’s an audience,” said Weir. “If I knew for a fact that no one was reading it, I wouldn’t do it at all.” That said, “I’m really much happier writing fiction.”

Should cartoonists do webcomics today? “It costs you literally zero dollars to make [a comic] and post it somewhere,” said Weir. “There’s no reason not to.”

“Unless somebody offers you a whole bunch of money to do something else. Then you should do that other thing,” said a remarkably perceptive and attractive panelist with excellent glasses. “But maybe do webcomics at night.”

The full panel will comprise an upcoming episode of the Masters of Webcomics podcast (http://whelon.com/series/urf/). All the panelists’ webcomics and/or bestselling novels are available through their respective websites. The way the protagonist of Demon gets out of prison is worse than whatever you’re thinking.