Michael Gross's lengthy career as an art director and producer has spanned era-defining work for The National Lampoon (where he pioneered the magazine's approach to comics and illustration, and in the process created a forum for some of the best cartoonists of the 1970s) to the look and feel of the Ghostbusters films. Here he discusses his education, ideas and most famous projects.

SHAUN CLANCY: You attended Pratt institute. What year did you attend?

MICHAEL GROSS: I went there in ’63, but I dropped out in ’66.

CLANCY: And at Pratt, you were taking illustration classes, or … ?

GROSS: Well, it was a weird thing. I came out of Newburgh, this little town, and I went to art school and I was really torn. I almost couldn’t figure out whether I should go out to California to try to get in the movie business or go to New York and be an artist. I opted for New York and went to school. I sort of recognized the idea that I could learn from the environment without actually having to take design classes, through my roommates, through basically osmosis. Because no one will ever give me the opportunity for several years again to train my hands to learn to draw better and to learn to paint. So as an abstract concept, the school was better for me to hone my graphic skills while the outcome was never for me to be an artist. It was really to learn about communications and design and advertising and editorial, magazine design—all through my roommates! And, as I said, osmosis. So basically, that was two educations!

CLANCY: Were any of your associates also in the industry later on?

GROSS: Well, Dave Kaestle was my roommate and Dave and I then we worked in New York. We did National Lampoon together and then later had a design firm called Pellegrini, Kaestle, & Gross. We designed for the Muppets and had all kinds of clients. He remained my best friend for life, much like a brother I never had. He passed away about 9 years ago. There was never a finer man. We were spiritually related.

CLANCY: Did you meet Glynis during the Pratt years?

GROSS: High school! I was 17 when we married. Lasted 30 something years. We got divorced, but then we remained best friends. We had done business together, traveled together even. Then she came to live here on the beach with me in her last year before she passed away. So I would say 40 years, but technically on paper it was 30.

CLANCY: And in high school, were you interested in the arts at that time?

GROSS: Oh, yeah, I had a great mentor called Val Warren and he passed away. It was a bad 3 years, my best friends, my wife, and mother all died within 3 years and that’s 8 or 9 years ago. But anyway, I digress. I had my first published piece in Famous Monsters of Filmland! [laughter] I sent off two paintings and they published ’em. Ironically, at Comic-Con this year, they’re going be showing their new issue, which is for the 30th anniversary of Ghostbusters and I have a feature article in it in addition to a piece on Heavy Metal as well. They’re really nice. A 16 year old kid doing these paintings—they were actually two paintings from Harryhausen’s 7th Voyage of Sinbad that I copied—and I sent them off. My parents said, “That’s great! Send it in!” What does “send it in” mean? Send it where? My parents had this weird thing about publishing. They didn’t understand it. [laughter] “Send it in!” So I did! I sent them in and they published them. I have them in my scrapbooks.

CLANCY: Were they covers?

GROSS: No, no. They were just inside. And they at Monster of Filmland were so sloppy. The captions were the wrong captions! [laughter] The one about the skeleton talks about the dragon and the one about the dragon talks about the skeleton. It was so funny. They didn’t even proofread their page. I’ve met with the owner of the magazine now and they’re really sweet and the new covers are fabulous. I’m really proud that 50 years later I’m featured in a magazine that published me for the first time in my life. So yeah, we made movies, I painted, I kind of wanted to be an illustrator but I also kind of wanted to be a magazine designer — but I really wanted to make movies. I also thought—when you’re 17 years old—I can do it all.

CLANCY: Do you remember what they paid for those?

GROSS: Oh, they didn’t pay. No, they didn’t even bother telling me. That thing was a few steps beyond a fanzine. But, hey, my room was covered wall-to-wall, when I was about 14, with full-page pin-ups—if you want to call them that—of the Famous Monsters monsters. I had Frankenstein, I had the werewolf. They were all on my wall! I should have been beating off to something sexual by then but all I had were monsters on my wall! [laughter] That’s why we’re all the geeks that we are. Meanwhile, at 17, I married the most beautiful woman in town, the most beautiful woman in my life. She was model-gorgeous and so geeks do win sometimes.

CLANCY: That seems to be the “in” thing now, to be the geek.

GROSS: It was never in. You know what? We were not really called that at all, you know? We were in a small town. I was lucky to have five friends all with similar interests. I wanted to go to New York where there were lots of people. But I also—it was always kind of a side agenda. I was a pretty normal guy. I was trying to date and drive my dad’s car. Actually, I met my wife when I was in study hall in high school. She was older than me so she was about to graduate. She was a senior and I was a freshman. I was sitting there and I was drawing a pin-up. I mean, literally a pin-up, not the monsters. A girl. I was drawing a pin-up in my homework book and she walked down the aisle and she said, “Wow, that’s really nice.” And that’s what started it all. One dirty picture.

CLANCY: You grew up in the ’60s. Did you ever get called up?

GROSS: No, because I got married at 17 so when the draft hit, they weren’t taking you if you were married. And they started taking marrieds, but I was married with a kid. They don’t take people married with a kid. And then when they started taking married with kids, I was too old. [laughter] So I have to say, my peers, like Dave Kaestle, my friends at Pratt, most of them took teaching jobs. Teachers were exempt. So they got out of school and that’s how easy it was. You could actually make that decision that you want to be a teacher and you got a job. Dave Kaestle went to Elmira, New York and taught college so he didn’t get called and Jim Newport who was a roommate, taught high school. He didn’t get called. So we had a few friends who volunteered. One went to Vietnam and was killed. And the other went to the Air Force, that’s Don Shay, the publisher of Cinefex, who was my high school buddy and did some magazines together and he lives here in Riverside near me. We’re still best friends.

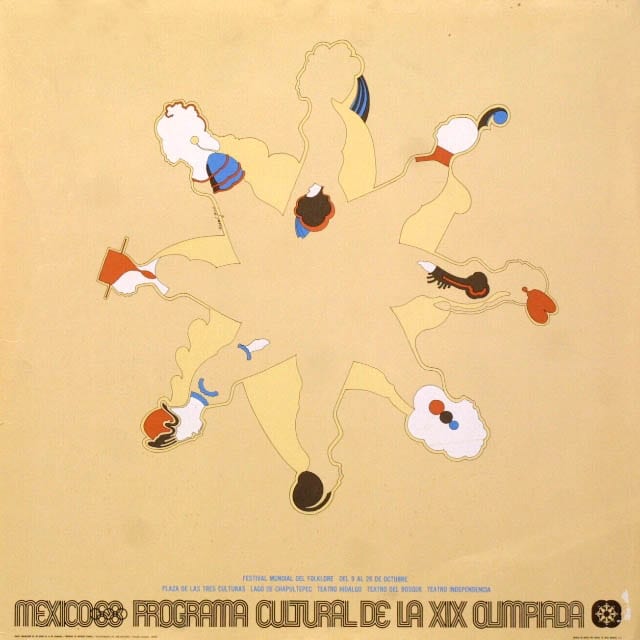

CLANCY: You did a poster for the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics. Would that have been the next project that you would have been working on since Famous Monsters?

GROSS: I was 23 and I had several editorial jobs working at magazines. My first job was the bottom of the rung at the art department at Cosmopolitan with Helen Gurley Brown for about 6 months. From there, I moved up to some magazine called Medical Economics because the great art director allowed me to do a cover, which usually takes 6 months to a year to move up the ladder. Your portfolio gets bigger, your knowledge gets better. So somewhere in there, Bob Pellegrini, who went to Pratt, was in Mexico City putting together teams to do the graphics on the cultural program that ran with the Olympics but it also ran for a year preceding the Olympics. There are only two modern Olympics that did that and one was in Mexico. But in Mexico, there were no designers. The Mexicans used their talent as artists— fine artists—or architects. There were no printer designers of note. They knew enough to need these very slick graphics but they had to go to the states to get them. So they imported a bunch of us young designers. It was an unbelievable opportunity, to work with the Olympics! I had a baby and a wife and had never been outside of America, didn’t speak Spanish, and arrived in Mexico City with 29 dollars in my pocket and my wife and baby. I said, “I’m here! Let’s go!” They hired me. They paid the plane ticket. It was the best year of my life. In 10 months we did a hundred plus pieces of graphics and posters. I was once in charge of three four-color presses, all printing my work! I looked at them, all spitting out posters that I did! And I’m 23 fucking years old! It jumped my career five years ahead so I already had this amazing portfolio when I went back to the states. At that point, still everyone was involved in the war so I didn’t have a lot of competition in the workplace.

CLANCY: In 1969, which would have been the year you got back, you were art director at Family Health. How’d you land that?

GROSS: I don’t know. It was a job. Look, the goal in New York City was if you were an editorial art director you were managing the design of the magazine and more than anything we wanted to show the business that this was our work. You rose, almost like the movie business scene in the off-season. You tried to rise to the day when you looked at a magazine, opened it up, and it said “Art Director” and your name was on it. And every move you made was trying to get further up the ladder. It was an opportunity, that’s all. I was there before I went to Lampoon. This was after Mexico.

CLANCY: Then Eye magazine was in there somewhere?

GROSS: I came back from Mexico to get Eye magazine. A brilliant art director whose name I don’t remember was killed in a boating accident, and they didn’t have anybody and I walked in with my Mexican credentials and my love of magazines and they hired me on the spot. I only did like five or six issues before, basically, Hearst changed it and it folded. It was at that point, kind of the hippest, coolest thing after Rolling Stone. It was a broader base but I was like a youthful hippy magazine art director. And here I was, living on $15,000 a year and I had arrived. [laughter]

CLANCY: When you had an Eye magazine office, was it shared with other magazines from Hearst or was it dedicated?

GROSS: We had a storefront down in the Village and it was owned by Hearst. Hearst was annoyed that we had our separate offices and weren’t in the Hearst Building. That was one of the problems of getting Hearst to publish the magazine. They wanted a rock and roll magazine but could we please not show too much long hair or talk about sex and don’t mention drugs! It’s 1969, okay? I don’t see how we could do that.

CLANCY: Did you start to try to experiment with humor at Eye or Family Health?

GROSS: No, no, but when I was at Eye, I suggested the “Funny Pages”. I had that concept for Eye. I didn’t like underground comics at all. I did like Robert Crumb but I didn’t like anybody else. That was short-sighted on my part ’cause there was a lot of talent out there. But that’s not the way I saw things. And I thought to myself, what if we did a section and we tapped Gahan Wilson, people like that who were funny who don’t do strips but who may want to do strips and it would be like an adult comic book section thing? And Eye magazine turned it down. Thought about it for a minute and said no. Then, when I did Lampoon, that was around a year later, I went to Henry Beard and presented the same idea. Of course, the attitude at Lampoon was “Fine, that’s eight pages less we have to think about!”

CLANCY: But how did you land that National Lampoon job?

CLANCY: But how did you land that National Lampoon job?

GROSS: Well, my assistant at Family Health was looking for a job—nice guy—and he got called up to Lampoon. He came to me and said, “You know, I got called up but I’m not right for it and they know I’m not right for it but you might be the right person to do this!” And I’d read their Time magazine parody and I said, “You know, I looked through the magazine and it’s a complete mess.” So my wife looked at it and she said, “Why would you want to work on that rag? This is terrible. I thought we were trying to get Esquire one day or, you know, Vogue! You were going to be a major player in the publishing world. This is a piece of shit.” [laughter] I said, “I think I know what I can do with that magazine.” So I applied. I went in for an interview. The story I tell is basically, Doug Kenney asked me—You gotta remember, Doug Kenney had just come out of college. So they didn’t know how to run a magazine! They were brilliant, but they didn’t even know what an art director did. And they hired an underground studio, because they thought, we’re not Mad so we’ll do the contemporary version which would be largely like underground comics. Now, I went in there and said, “No, no, no. You’re doing this all wrong. Matty Simmons, the publisher, was looking for a new art director because he couldn’t get advertisers with that look to the magazine. They wanted to be slick. That’s his only answer. So I was called in, and Doug Kenney was probably told they had to replace the art director but I’m not really sure and I sat with Kenney and I remember distinctly that they did a series of postage stamps.

I said, look at these stamps, you did these postage stamps. They’re very funny. But their drawings are by underground comic book artists on every stamp. I said, this is like Mad magazine, where they have Mort Drucker do every drawing. This is not the same. The way that this will pay off is if they look like real postage stamps. Then the humor is doubled. And they got that and that’s what I hoped. And that changed the magazine. It was a reflection of my vision.

CLANCY: When you joined, who was on staff in the art department?

GROSS: They didn’t even have a staff. They outsourced it to Cloud Studios.

CLANCY: And Cloud Studios was an underground group?

GROSS: Yes and we kept some of the artists working on the magazine. They did some nice strips now and then. But their photographers were shit. They couldn’t design. They knew nothing of design. It was to me, sort of a black and white situation. Execution is everything. And most of what it was about was understanding what the joke was and then interpreting it correctly. And they weren’t doing that. They interpreted everything as their way.

CLANCY: Did you have any trouble with Mad magazine?

GROSS: No, and never interfaced with anybody there. We thought we were competition. It’s kind of funny because Marvel Comics was upstairs from us and …

CLANCY: I didn’t know that.

GROSS: We interacted all the time. I’d run upstairs. I’d borrow a letterer if we needed lettering done on FotoFunnies. They did a lot of coloring on some of our comic strips. We had a good relationship with them and I’d go upstairs and say, “Stan, I got a comic and I don’t know who’s available. You got anybody?” He goes, “Well, yeah, you know who’s available? That guy over there. He can do it. He’s not working right now.” So we had a good relationship.

CLANCY: So that’s how you got the artists for National Lampoon?

GROSS: Yeah, that was the start. I had an interest in comics and knowledge but I wasn’t a collector. I was very aware of them. Basically, they educated me. How’s it work? I didn’t even know you had pencils and then inks, you know? I had to learn all that! Which was learnable in 24 hours but they also had artists who really appreciated what we were doing. So in terms of Mad, no, we were competition and never interfaced. Then we did that parody of Mad, which was the proudest thing I’ve ever done for National Lampoon. There was never a reaction to that over there.

CLANCY: Was there any criteria set that you couldn’t do? Any type of rules you had to follow?

CLANCY: Was there any criteria set that you couldn’t do? Any type of rules you had to follow?

GROSS: Well, we were the kings of not following any rules. [laughter] I don’t remember ever once … You know, I think we even had pubic hair. I’m not sure. In fact, I would guess if I were, today, looking at them, at my point of life, I’d be very upset at some of the things we published. We did things like Christ on a cross vomiting. You know, it was ok but today, I would think, “Jesus, that was offensive.”

It was an amazing time in publishing and not just the world of publishing but specifically in terms of what we were able to do. And that was because nobody told us not to! Matty didn’t know what he had. He was always having advertisers dropping out and they were paying him and we didn’t give a shit. As long as he paid us and we got to do this! And then it grew and then, when it grew it really grew!

CLANCY: Do you remember the circulation numbers?

GROSS: I think it was 14,000. Then we realized it was passed around and we had an advertising staff that made the huge mistake of always pursuing Coca-Cola. I mean both literally and metaphorically. It’s like, “We’re going to get Coca-Cola and General Motors.” You know what I mean? [laughter] And once in a while, they’d try it and the next issue would have a piece we’d run that was so offensive, “We’re not gonna advertise with you anymore.” And they were struggling. They got a brilliant ad director. Shit. I’m sorry. I can’t remember his name but a great guy. He said, “What are you doing messing around here? What you should be doing is getting Pioneer Electronics! You’ve got a college crowd that has no place to advertise except Rolling Stone.” And he pulled it out. He sold so much advertising, all based on our audience. You’d think that’s simple, wouldn’t ya? But in those days, it wasn’t so clearly defined. Then it became a success, a financial success and, at the same time, we were breaking out and doing the radio show and albums and blah-blah-blah and moving onto the stage and had Bill Murray getting involved and John Belushi’s wife was my assistant in the art department.

It morphed into something larger that no one had any real control of. Matty Simmons thought he did but it was more like it was a force of nature that had taken place that he didn’t know how—it was like riding a bull. He had this thing. He created it but he didn’t know how to ride it.

CLANCY: You designed most of the covers for National Lampoon. There are some that are uncredited but I’m going to have to think that you had something to do with some of those covers too.

GROSS: Yeah, I did them from the ’60s Nostalgia issue, and that was November or something—my first issue—and I did them for four years and change. But the reason it’s vague at some point is because I also broke out from the magazine with my design firm when National Lampoon was acquired. They did special editions like the Bicentennial Calendar or the Encyclopedia Britannica. And then there were special projects that the editors were only comfortable bringing to me and I was an outside design firm. So it’s weird with those two credits because you can’t tell when I was there and when I wasn’t. We had Peter Kleinman who was the brilliant art director who came after me and he picked up some pieces of what I did so it kind of morphed.

CLANCY: The famous cover with the dog—“If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog.” That was your idea? Do you remember the backstory behind having that cover and was there any fallout from it?

CLANCY: The famous cover with the dog—“If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog.” That was your idea? Do you remember the backstory behind having that cover and was there any fallout from it?

GROSS: No fallout. It started with an ad campaign with Ed Bluestone, who was a comedian at that time. Ed conceived that we would do our own in-magazine subscription ads. There were only 10 people working there. He said, “Okay, we’re gonna run a bunch of ads. One page asks ‘If you don’t subscribe to this magazine…’” Subscriptions back then were very important. Maybe they weren’t with all magazines. I don’t know. But they were very important. “If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog.” We never ran that and then what we were going to do was, afterward, next month we’d show, kind of under a blanket, some dog’s feet. We’d killed the dog. There’d be a cat and, “Ok, you didn’t get it, did you? Now we’re gonna kill the cat.” And it was going to escalate over months where there was like all these dead animals. We never ran it. It was just kind of an idea. And then we happened to do the “Death Issue” which is singularly the best issue that magazine ever published. Everything in it is brilliant, everything in it is beautiful. Every parody is great, the Playboy parody is great! It was a really exceptional issue of the magazine. We were at our absolute apex and our zenith. When was the last time you heard somebody say “apex” and “zenith?”

CLANCY: [laughs] There weren’t any lawsuits from that?

GROSS: We made up these themes almost arbitrarily, just to give us focus. We’d say, “Death”. “That sounds good.” One day we were looking for a cover idea and we said, what about that idea that Bluestone came up with for the ad campaign? You know, killing some animal. I said, yeah, yeah. We did that and it was amazing because it was pre-Photoshop and we couldn’t even afford to add transfer or retouching as it was a major deal. We got one shot where the dog’s eyes are actually turned like that. And we knew it was a great cover. I didn’t know it would be rated one of the great covers in the history of American publishing. I have books in here, talking about magazine covers, and that cover’s in there. I have a book that’s a history of magazine covers and it lists 7 examples of the origins of brilliance. It includes the first issue of Playboy and it lists that cover and I think there was some kind of thing by some publisher, I don’t know who they were but they rated it #7 of magazine covers published over the last 50 years. I thought, you know, hey, cool!

CLANCY: Whose dog was it?

GROSS: It was a rental. A hired dog. We had to hire an animal trainer because you have to be able to, you know, be sure the dog will sit and stay there. Simple stuff but you don’t think about it. Somebody wanted a German shepherd. I said, no, no, no. We had to have a certain kind of dog, sort of like an Our Gang comedy. There’s got to be a big spot over his eye or something. He’s got to be just so loveable. Anyway, we had to book a dog. Ok, you animal guys, what do you got out there? I need a loveable dog. In L.A. it wasn’t that easy. They didn’t have animal trainers.

CLANCY: Was there a professional photography studio that was doing the shoot or did you use your own studio?

GROSS: No, no. We used Ron Harris. Ron did a lot of shooting. Ron shot for me and my partner, may he rest in peace, Dave Kaestle. When you’re in editorial, you had to go and say “Hey, I got a cover for ya and I can pay more than the other one.” And every month it gave him a little work. A little here and a little there. And basically what they looked at was a steady client. And I used maybe four photographers that way so that every issue I would call one of the four with whatever particular skills. And they were all super photographers because that’s all they did. And it kept everybody working, everybody happy. We were all young. We were almost innocent and we just plowed along and did what we could. Maybe it shows in the magazine, I’m not sure, but what’s more important about it was that we would use our innocence and our naïveté to keep the freshness. We can just do this and have fun doing it and the smartest people will come to us and the smartest people did! The smartest people in American culture in the last half of the last century were at National Lampoon. Bill Murray, John Belushi—they all came out of Lampoon. And we knew that at the time! Everyone was just trying to figure out how do we get paid? [laughter] Enough of this “influential.” Would somebody show us some money?

CLANCY: You were personal designer for John Lennon as a consultant and also a consultant on the Muppets. Is that accurate?

GROSS: Yes, very accurate. Dave Kaestle, we tended to design things together when we lived in that design world and David’s wife at the time worked for the Muppets. She designed or at least constructed Miss Piggy and we got to know Jim Henson pretty well—visited his home. We just took on that design work for the Henson Corporation along with Chris Cerf, who’s still part of the Henson and television business. We were a circle of almost elite publishing designers of a certain genre in New York. So that’s how we got to work with the Muppets.

CLANCY: When you say you were doing design work, was it set design?

GROSS: No, it was graphic art. They needed a Henson Associates logo. We did a HA! H-A-exclamation point. Which is a great logo for them. Yeah, we did that, and we did print work. It was more like a business in the sense that they would call on us to do graphics, give some feedback.

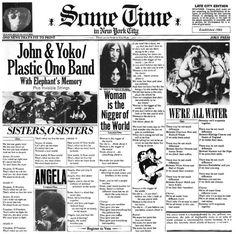

John Lennon was a separate thing. Oh, God! It’s almost a long story. I can’t go into the whole story because it’s too long and I’ve told the story many times before. What happened in the end was that John Lennon loved National Lampoon. He and Yoko needed a personal designer, that is someone who would take care of just some of the things like Christmas cards, a book she wanted to do, any of their personal crap unless it didn’t fall under a record label. And they said—their people, I don’t know who it was— that I had to be available at night. So I was working two jobs, doing a magazine and at night I was working with John Lennon. It eventually burned me out. I couldn’t do two jobs at once, much less sleep. But I had the privilege of working with John for about a year. And knowing him, not intimately but like most people when you’ve worked with somebody for a long time.

John Lennon was a separate thing. Oh, God! It’s almost a long story. I can’t go into the whole story because it’s too long and I’ve told the story many times before. What happened in the end was that John Lennon loved National Lampoon. He and Yoko needed a personal designer, that is someone who would take care of just some of the things like Christmas cards, a book she wanted to do, any of their personal crap unless it didn’t fall under a record label. And they said—their people, I don’t know who it was— that I had to be available at night. So I was working two jobs, doing a magazine and at night I was working with John Lennon. It eventually burned me out. I couldn’t do two jobs at once, much less sleep. But I had the privilege of working with John for about a year. And knowing him, not intimately but like most people when you’ve worked with somebody for a long time.

CLANCY: At this time was any of the movie stuff starting to heat up? Heavy Metal or any of that?

GROSS: Well, it depends on when you say “this time” but what happened was Matty Simmons connected with Ivan Reitman through Animal House. Reitman knew Harold Ramis who had worked on National Lampoon, cabaret show, etc. What happened was he got a soup of the best kinds of the changing attitude in show business. Everything was changing. It was the late ’70s. There’s a shift in independent thinking, particularly comedy. I was kind of just on the peripheral of it because I only had my design firm, but I got tired of that and I was doing freelance work. I was floundering. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I did some freelance work back at National Lampoon! They had an office for me. It was kind of, in some ways, sad. If you looked at me and saw me in an office in the back largely contributing to Heavy Metal which was a system of attrition. It didn’t quite pay the bills and I did other b.s. work but in those days, before computers, I needed services, I needed Photostats. I needed an office, a phone number. So, as a freelancer, I was grateful to have this little office someplace and I was trying to figure out what to do with myself at that point. All their most talented, best people had already moved to California! They’re out there going, “Come on out, Mike! The weather’s fine.” [laughter] And because Heavy Metal was a publication of National Lampoon and National Lampoon had already done Animal House, the partner Len Mogul was the other publisher of 21st Century Publishing. He wanted his own movie. So he said, “How about if I take the information from Heavy Metal and the rights we had and give it to Sean Kelly. He tried to sell it, and I was there in the office one night and I said, “I know a lot about animation.” I lied. I knew something. After all even a 14 year old knows something. I said, “The real problem’s gonna be you’ve got all these pieces of art that look so very different from each other, you’re gonna have to train animators to all work this way.” Meanwhile animation was dead at that point. The animation business was really in bad shape. I thought my job would be to try and bring the best of the best and make it work. Well, they bought that. Eventually, they got the likes of Ivan Reitman. And Ivan said, “I can get that made in Canada with a phone call. So bing, bang, boom, I’m in California and I’m in the movies and the rest is history.

CLANCY: With the content of Heavy Metal, were you involved in deciding the storylines?

GROSS: We lost the rights to a lot of the French material so we had to originate new material. Our designers and art directors and a lot of other people got together and they also built an animation studio in Montreal, not to mention studios in New York, London and Toronto. It was extraordinary.

That movie was made for 12-16 year old boys in that period. It’s tits and ass, it’s fast, it’s funny. It had things you had never seen animated before. You hadn’t seen a girl’s tits animated before that. And it’s like, “I’m in heaven!” What could be better if you’re a young teenage boy?

CLANCY: Now, you had Bernie Wrightson working on that. Did he work in the animation studio with you guys? Do you remember Bernie at all?

GROSS: Bernie and I go back. I have a very special relationship with Bernie. Now, in the movie, his material was actually the purest, because his style was so animatable.

CLANCY: Yeah, the Hanover Fiste thing.

GROSS: Yeah, so his comics style alone—that’s animatable. You know? And he was. And he always said, “God, this is perfect!” He’s one of the few artists who watched their work come to life on film and said, “Perfect!” There was always so much frustration because we didn’t have much money and we couldn’t quite deliver a lot of stuff like we should’ve. And then, for Bernie, it was kind of a pure experience. He’s a wonderful man! Believe me. I would have to guess, between the film and the magazine all told, I probably worked on 40 or 50 assignments with him.

It’s very difficult to talk about yourself in terms of what you think your qualities are without sounding like you’re tooting your own horn too loudly, but I think one of my proudest achievements was that my relationship with artists was always really honest. I got them paid, I treated them well, revisions were minimal. They knew I was hiring ’em, they knew what they were in for and I knew. I placed them perfectly for what their job might be. So, as an art director, that’s your skill! That’s your thing. To see it realized over decades now, I have to give myself that credit. And I had that relationship with Jeff Jones, I had it with Bernie, I had it with Vaughn Bode, I had it with Gahan Wilson. It’s just a question of what do you do as a good editor when you’re using your talents? That’s what an editor does! And I pride myself on the fact that I have a very good relationship with all that talent.

CLANCY: Russ Heath, Ralph Reese—they all speak very highly of you. That’s very uncommon in the comic book industry.

GROSS: Oh well, I’m the only guy that seems to speak well of Stan Lee these days.

CLANCY: I didn’t know you kept in touch with Stan.

GROSS: Stan and I had a very nice relationship and in later years, when we were both new in Hollywood, he had this little office someplace and I hadn’t seen him in 10 years, something like that. I can’t keep track. And he was trying to get a movie made. I was, at that point, may have done Heavy Metal, maybe I’d done Ghostbusters. I’d have to look at a calendar. And when I saw Stan I said, “Boy this movie business is tough, isn’t it?” “Yeah!” And he talked about how he can’t sell any movies and he’s working on it and I tell him, “Well, we would do it but that’s not what we do.” I would back a couple of your things but Ivan Reitman doesn’t like comics and it’s not what we do. I look back at those times and later, he’s one of the most powerful men in Hollywood! And you know, God bless him. I don’t care what anyone says about Stan. I don’t judge people by what other people say. I judge them as best I can by my personal experience and Stan was always terrific. So I have nothing bad to say about him. I think he deserves all the fucking credit he gets.

CLANCY: Now, Heavy Metal was done in Canada but you were in California trying to get it distributed?

GROSS: Ivan Reitman comes out of a history of getting Canadian films made that actually made money. He actually produced one of the first nudie scary pics of the ’70s and yeah, they’re kind of shoddy underground entertainment, you know? With independent filmmakers. So with the movie deal—Heavy Metal—originally there was some issues with 20th Century Fox. They paid some development money in cash. Then Rollo was desperate and because Ivan had done Animal House, he called Ivan and said, “Are you interested in something about Heavy Metal?” and Ivan said, “I love the idea.” SWe did it in probably three countries, eight animation studios. We did it in record time and we at Ivan’s shop had never done animation. I flew 81 flights in 18 months. [laughter] Between London, Montreal, Los Angeles and New York. Sometimes I was so tired. I was always chasing a crisis. And at some point I was so exhausted, I was on a plane saying to myself, “Where am I going?” I’m on a plane but I don’t know where it’s going. It scared the shit out of me! I’d be in London and I’d say, “I’m flying back to Los Angeles tomorrow,” and they’d go, “No, no, no. You’ve gotta go to Toronto. Because there’s a terrible problem in Toronto.” So I would just change the flight, right? I didn’t know where I was going! And I said, “You can do this, Michael. Without looking at the ticket, you can do this. [Gross pauses] Ok, I’m going to Montreal!” And I turned the ticket over and it said Montreal. It was insanity. How bad does it get when you’re that exhausted. Let me tell you something, when you don’t even know what fucking flight you’re on, you’re in trouble! I was flying for months, just patching up problems, and then every three days or maybe a week I’d say, “Should I come back to Los Angeles?” “Yeah, come here. We need you here.” So I go to Los Angeles. By the time I’d get to Los Angeles, the problems were mounting in London. So the next week I’ve got to go back to London. And they installed—or instituted or whatever the word is—frequent flyer mileage on my last flight! And none of it was retroactive. I was so fucking pissed! 81 flights in 18 months and I can’t gain a mile!

CLANCY: Did people pick up the movie to distribute at all? Did you have a tough time getting it to theaters?

GROSS: No, not at all because Ivan had a very good position then. He came out of Meatballs as a director and was on a roll in the same way as Cheech and Chong, and it was that whole semi-sort of independent underground, youth-oriented filmmaking. But the studios weren’t sure of it yet or how to pick it, so he was obviously the person entrusted to do this. So this was a man who could deliver a film. National Lampoon, Second City—which we were in the middle of. It was a great time for making those kinds of movies. So Columbia backed Stripes and Heavy Metal at the same time.

It was heaven—we’ve got a distributor, we’ve got a budget, we’ve got money, we’re financed. Let’s just make the goddamned movie!

CLANCY: Was it over budget?

GROSS: By about a million. I’ve never seen a profit from it. I’ve never seen a check from it. To give you an idea how skinny the dollars were, I think it was budgeted at eight to nine—something like that. It was enough to make a profit, but it costed 11.

CLANCY: Now was Ghostbusters second on your list?

GROSS: Yeah. I did some uncredited work in between on Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone. [laughter] I also contributed to National Lampoon’s Vacation. I designed the car. I designed Marty Moose, I designed Wally World. I’m uncredited.

CLANCY: The moose he punches in the face?

GROSS: Yeah. That statue, they asked me if I want it in my office. I said, “No. Just take it away.” Now it would be fun to have today! With my first movies, Heavy Metal and Ghostbusters, my title on both pictures is associate producer which, today, is a meaningless sort of title but in those days it meant something. My job as an associate producer, producer, or executive producer has always been the same: Just get the movie made.

CLANCY: [laughs] And stay on budget.

GROSS: And pre-production and time set for development and post. Not just post-film but advertising and promotion. I’m a full producer in every sense on all those films, regardless of what the title is. I remember Ivan asked Joe and I, “Okay, what do you want? You want executive producer and I’ll be producer or I’m executive producer and you’ve got the producer?” “Whatever you want.” I said, “I don’t give a shit!” Call it what you will. The only place it makes a difference is if you’re nominated for the Academy Awards as Best Picture, they only go to the producers. You think that’s going to happen with any movies we’ve made? I don’t think so!

CLANCY: Bill Murray was both in Meatballs and Stripes, so I’m assuming that’s how you got him on Ghostbusters.

CLANCY: Bill Murray was both in Meatballs and Stripes, so I’m assuming that’s how you got him on Ghostbusters.

GROSS: Yeah. Well, sure. In fact, it was about the end of Ghostbusters in which the industry even looked to Ivan and said, “You know, you’re really good but who are you without Bill Murray?” You know what I mean? Bill’s whole thing was, he had a great relationship not just with Ivan but with Harold Ramis. Rest in peace. So, it’s like a bunch of guys making… fun! There’s no corporate influence and we were not entirely like independents. You know, we weren’t shooting this in some backyard. But, at the same time we had the power of the studios but the power that Ivan brought with him always was, “I shoot cheap, fast, and I’ll deliver on time and have a hit.” And he delivered consistently. So we had great freedom. I never had to go through “How do we raise another nickel?” or how many corporate big people do you have to have approve your script or any of that crap. We had a magic period, maybe, being the end of independent thinking but within the studio system.

CLANCY: Well, staying on the comic book connection and animation, The Real Ghostbusters was an animation show on TV. How did that come about?

GROSS: We did the first movie then sort of walked away from the franchise. We had no merchandising on the first movie because it was a surprise to everybody. And merchandising has to be done in advance. You can’t sell a toy company on a toy if they haven’t even seen the movie yet and so they wouldn’t commit. It’s a long process and a financial process. And that goes all the way down to even T-shirts. There was no merchandising at all for that first film. So what happened is, it sort of ran out of steam. We didn’t need the bucks back then. We moved on, did some other things. Then what happened was about a year or two later—are you familiar with the background of Filmation? Filmation did a live television show for one season once called Ghost Busters. So in terms of us getting the name, we tried other titles. They didn’t work. We simply said to Columbia, “Go to Filmation and buy the rights to the title, Ghost Busters.”

We called up Filmation and they said, “Fine, but because we’re an animation company, we want the rights to do animation.” At that point, nobody in Columbia thought there’d ever be animation and no one gave a fuck and we were desperately trying to get the title so we said, “Fine.” They can’t do live action, they can’t do anything based on these characters, but they can have the name, Ghost Busters. So we do the first movie, comes out, it’s a huge hit and Columbia comes to us one day and says, “We have a problem. Filmation is gonna do a Ghost Busters animated show, now. They have to because ours was such a success. It won’t be based on the same characters...” Blah, blah, blah... “We can’t let them do this! We will blow our opportunity to do an animated show.” And we, at that point, since we weren’t considering a sequel, said, “Fine. Whatever works out.” So we said, “What we’d like to do is do our own animated show but we can’t call it Ghostbusters so what we’ll have to call it is, The Real Ghostbusters!” I mean, both came out simultaneously. Obviously, their Ghost Busters died. I’ve never even seen one. And The Real Ghostbusters took off for obvious reasons.

And then we ran our animated show for 5 years and that then generated the merchandising because in the merchandising business, merchandisers like Mattel love nothing more than something that has longevity. So if they assume a TV show is going to run three years, they can gear up a toy line going in a year, blah, blah, blah, blah. So the whole thing morphed from film to TV and everyone’s happy and we made some money in the franchising of stuff. We didn’t want to come back. We didn’t want to keep this thing going. We had other movies to make. And then, somehow, later, Danny [Aykryod] in his great enthusiasm—Danny is not only the creator but one of the great believers in the Ghostbusters franchise. It was his baby, if you will. And he says, “Why don’t we do another?” It was five years later and there’s been a television show, Slimer became a character and everybody sort of, wanted to do it, including Bill Murray. And so we did the sequel. The give and take in the whys and the wherefores between the first film and the second film and the television show and how they would work together was another question. The second film didn’t do as well but it was still a hit.

CLANCY: In 1995 you left Hollywood. Was there a reason for it? It was time or did something happen?

GROSS: I think I had a little too much money in my pocket and I’d been in publishing in New York, I’d been making movies in Los Angeles and I couldn’t take watching the [O.J.] Simpson trial anymore. I wanted out of this country and decided to go to Italy and to be a painter and be out of the business and start life all over again. It didn’t work out. I wasn’t a painter. I couldn’t speak the language and I found out that Italy was quintessentially America. Came home and I was out of the business. Things had changed. And instead, I did some of this and that, design work and some consulting instead. I was a museum curator, a painter and live on the beach and basically out of the business and I’m glad of that.

CLANCY: Was there a movie you weren’t able to make that you tried to get made that just didn’t happen?

GROSS: I tried to make Hitchhiker’s Guide and I worked for four years but we never got a script that worked.

CLANCY: Do you still do the comic conventions?

GROSS: Yeah, I’m supposed to go next week, but I’m not sure. It’s crowded and horrible. [laughter] I’m trying to tell my girlfriend, who hasn’t been to one, about the crowds and the noise and that she’d be miserable. I’m past that point but I’ll probably go over there again. Such is life. I need to see some people from New York I haven’t seen in a long time. I reconnect with Neal Adams every time I’m there. I contribute to a charity on cancer research.

CLANCY: Would you have any advice for someone who was trying to enter into producing films or anything like that?

GROSS: No. Zero. It’s a different business now. The only advice I have is the same advice I was always given—the same advice everybody gives—is follow your dream, blah, blah, blah. But if you don’t fight for it, if you don’t want to do it more than anything else in life, then you won’t do it. There’s somebody behind you who does want to do it more than anything else in life. That’s what they say to actors. You want to act, then it’s got to be your life. If not, then the guy behind you does want to make it his life. That’s a certain truth that I’d give anybody in this business or otherwise. But specific advice? Nah, nah, I’m too out of touch. My son’s in the film industry and he tells me about what he goes through and it’s kind of funny comparing today to my time in the industry.

CLANCY: You could probably trust people back then if someone gave you their word.

GROSS: Yes, you could. I’ve never had a signed contract with Ivan. I did 11 pictures on a handshake and I still get money today. You think you could do that any more?

CLANCY: This last question doesn’t have anything to do with that. I talked to somebody who worked on the sets of the National Lampoon’s Vacations and they tell me that Chevy Chase was extremely difficult to work with and I’m just curious …

GROSS: Oh, he’s one of the great hams of the world and you can quote me. Bill Murray and he on Caddyshack weren’t even speaking. When they both were in a scene they both were being very professional. Neither one of them would say anything because they were professional but Chevy Chase is one of the greatest assholes. I’m old enough that I don’t mind being quoted as saying that.