On a cold Friday the 13th in December, just hours before the first major snowstorm of the year crippled the Midwest, I met with Kevin Huizenga at his home studio in St. Louis. An unassuming suburban house from the outside, inside it was like a comic book utopia. Bookshelves filled with an ecsuperlectic assortment of comics past and present lined several walls. A framed Whitney Biennial print by Chris Ware hung in the hallway. Pinned to a bulletin board next to the drawing table were various process notes, sketches, and a print from Ganges #2 featuring a smattering of clouds viewed through the tree line above a scene of video game-inspired mayhem. Piles of minicomics were strewn about in disarray, while a neatly arranged stack of his latest Pocket Guides sat on the side table next to a reading chair. The room was a personal shrine to Huizenga’s passion and I immediately felt right at home.

On a cold Friday the 13th in December, just hours before the first major snowstorm of the year crippled the Midwest, I met with Kevin Huizenga at his home studio in St. Louis. An unassuming suburban house from the outside, inside it was like a comic book utopia. Bookshelves filled with an ecsuperlectic assortment of comics past and present lined several walls. A framed Whitney Biennial print by Chris Ware hung in the hallway. Pinned to a bulletin board next to the drawing table were various process notes, sketches, and a print from Ganges #2 featuring a smattering of clouds viewed through the tree line above a scene of video game-inspired mayhem. Piles of minicomics were strewn about in disarray, while a neatly arranged stack of his latest Pocket Guides sat on the side table next to a reading chair. The room was a personal shrine to Huizenga’s passion and I immediately felt right at home.

As we grabbed beers and settled in, Huizenga initially acknowledged a certain level of trepidation about doing interviews (“I don’t know what I just want public and what I want to hold on to”). Nevertheless, over the next couple hours, we had a fascinating conversation which covered everything from baseball, Buddhism, and philosophy to Scott McCloud and ‘90s-era Captain America comics. -Marc Sobel, May 2014

“I was going to be a minister.”

Sobel: You’re not actually from St. Louis; you’re from outside of Chicago, right?

Huizenga: Yeah. I grew up in the southern suburbs of Chicago in a small town of Dutch immigrants named South Holland, Illinois. It was your standard quiet little suburb. They even had “blue laws” where everything was closed on Sunday, and there was this community of Dutch immigrants that stayed together, although it was starting to unravel at that point already. It was a Dutch crew that lived originally I think in Roseland, in Chicago, and then moved out to the suburbs. When I was growing up, they were already starting to move out from the interior ring of the suburbs to the outer rings. It was a classic “white flight” situation. We lived where Indiana and Illinois become a sprawled area that they call “Illiana,” so a lot of the time you’re just going over the border, back and forth. A lot of my relatives lived on the Indiana side, so eventually my parents moved to Indiana, and that’s where they live now. But it’s really not that far from Chicago.

Were your parents Dutch immigrants?

No. They were fourth generation or something like that. Most of the people I knew growing up were Dutch and Christian. As I’ve gotten older and moved around, I’ve seen that not everybody has that kind of experience growing up in a cohesive ethnic community.

What do your parents do?

My dad’s an accountant for the carpenter’s union in Chicago. He’s a pretty conservative guy, though. (laughs)

Does your mom work?

Yeah, my mom’s been a nurse for forever.

Do you have siblings?

I have a younger sister. She lives in the North suburbs of Chicago now and she’s got two kids.

So what brought you down to St. Louis?

Well, I went to college in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It was a Christian college, and originally I thought I was going to be a minister. But before I even got to seminary that all changed. But I stayed there in Michigan for a year after I graduated, and it was a miserable, lonely life. Most of my friends had moved away and I was working at this place that distributed sewing and arts and crafts supplies to stores like Ben Franklin around the country. It was a warehouse and I did some of the catalog work. It was an OK job but I felt like I should be doing something more. Anyway, I was going to be in an anthology—it never came out—with a bunch of people and somehow through that I started emailing Ted May, who was also going to be in it. We became friends through email and he said that he worked for this company in St. Louis that was hiring cartoonists and that I should come down and visit. So I came down thinking I was just gonna hang out, but they hired me that weekend… or maybe I did two trips, I can’t remember. I got hired and I jumped at the chance to get out of Grand Rapids.

When was this?

This was 2000. I worked for that company for almost exactly a year, and got laid off, because this was on the downward slope of the dotcom boom. I surfed that wave for a little while, made some money, and then got laid off, but I stuck around and then I worked at the St. Louis Science Center for four or five years.

What did you do there?

I was in the design department. Mostly signage and miscellaneous stuff. I met my wife while I was working there—not at the museum, but during that time, and we got married and now I’m down here for good. It’s been fourteen years now.

Do you like St. Louis? Are you settled here?

I like it as well as I’ve liked any place. It beats northwest Indiana, and it beats Grand Rapids. (laughs)

You went to seminary college?

No, no. It was a liberal arts college, but it was Christian. It’s called Calvin College, and it’s run for the most part by and for Dutch Calvinists. Not like the Amish Pennsylvania Dutch or anything, but more like a liberal kind of Dutch Calvinist, which I guess is a strange thing to picture if you’re not familiar with it. It was one of the colleges connected to the Dutch community that I grew up in. When you grow up in a church-going world and you like to read books, and you’re a thoughtful person, or a bookish person, people will tell you, “Oh, you should be a minister.” So I was like, “Okay, yeah, I guess that’s the place for me.” Some of my friends were preacher’s kids, so it didn’t seem that far-fetched an idea.

But that changed once I got to college and got more realistic. I thought being a preacher didn’t fit my personality, and anyways that’s not what I want to do. I was already drawing comics all the time and that was what I wanted to do. I think the idea of writing sermons every week was attractive to me, as a kind of creative outlet. But I realized I wasn’t cut out for it, even though I was still pretty serious and earnest about my Christian faith at the time.

Were you studying art in college?

I wasn’t taking art classes at first, but I took one at some point for credit, and I showed the professor some of my comics. Already at that point I was drawing and printing mini-comics. I was really into it. The professor was like, “Why aren’t you taking art classes? You’re an artist already.” I was like, “No, I’m just a cartoonist, I’m not an artist.” (laughs) But he was like, “You’re an idiot, of course you’re an artist. You should be taking these classes.”

So he talked me into taking art classes. The classes didn’t help much, but where maybe the momentum of my life was going one way, that helped push me towards taking my comics seriously and thinking of myself as an artist. Even though I knew it was absurd, I knew that whatever I ended up doing for a job, I was going to keep drawing these comics forever. I mean, I didn’t think I’d do it as a career, like study it in college or anything. At the time that wasn’t an option. But I definitely knew that that’s what I was interested in.

“That was my ‘Road to Damascus’ moment.”

So you started drawing comics before you took any formal art courses?

Oh sure.

How did you learn to draw?

I was not one of those people who drew as a kid. That seems like the usual cartoonist experience. My family was more sports oriented. My dad was very into fast pitch softball and basketball. I was athletic growing up, so I played sports all the time, baseball, all that stuff.

But also, when I was a kid, I was allowed to roam the town, like for miles all around, and I would make these long trips to the different drug stores that had spinner racks. Once I found out about comic book stores I’d ride my bike there. When I think about that now I wonder, is that world gone or are kids still allowed to roam around like that? So shortly after buying my first comics I was trying to draw the characters.

This was in the ‘80s?

This would have been like ’89.

I had friends in the neighborhood who were also into comics and suddenly we were all drawing. In high school, we kept drawing our own superhero characters. Then we figured out that we could go to the Jewel-Osco and Xerox our comics. That wasn’t until ’93. As a kid, that was my “road to Damascus” moment, figuring out that I could make a publication of some kind and then print it. It was such a thrill that it was like, everything in my life and my mind just organized itself around that from then on. I haven’t been the same since. To this day, all I really think about is working on the next issue or the next book of something.

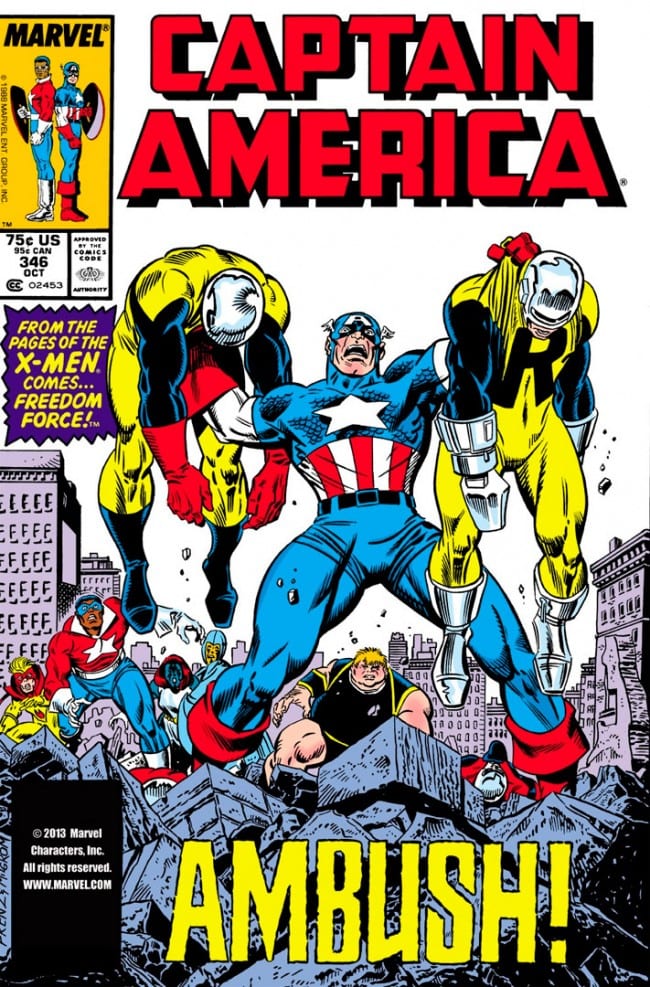

On the plane over here I was reading all your interviews I could find online and in one of them you were talking about how Kieron Dwyer’s Captain America comics from the ‘90s were an early influence.

Those were the first comics I ever bought. Kieron Dwyer. I still have them.

So were you literally copying panels from those issues?

No, I wasn’t copying panels. I would look at things to get a sense of how to draw, but I never really copied exactly what I saw. Maybe if I had I would have learned more. I actually don’t think I ever actually drew Captain America. It wasn’t until I saw the Punisher or Wolverine that I was finally like, “oh, I need to draw this.” (laughs) There’s something about the Punisher that flipped that switch. (laughs)

I think we all read superhero comics at one point or another.

Yeah, not everybody, of course, but…

Maybe not as much in the younger generation, but if you grew up in the ‘80s…

Yeah. I definitely did. Then, for a long time, I really reacted strongly against superheroes. I just didn’t want to hear anything about them and I resented that other people were even interested in them. I was like, “How can you still be interested in this?” Since then I’ve come back around again a little.

Our society is so saturated with them now. It’s like we’ve reached peak Spider-Man, you know?

Well, I feel like in a way they’re perfect commodities. The entertainment business needed some perfect commodity to sell and resell and resell and, for some reason, it took them a long time to figure out that it could be superheroes. Or rediscover it, I guess. Maybe technology and CGI had to catch up with the stories so they could show the wonderful, magical, awe-inspiring images and the dynamic violence. But now it’s like all the gears have matched up and the machine is rolling.

“I was in-between. I still feel that way.”

So you said you didn’t start drawing until you were 13. Were you writing younger than that? Were you ever an aspiring author?

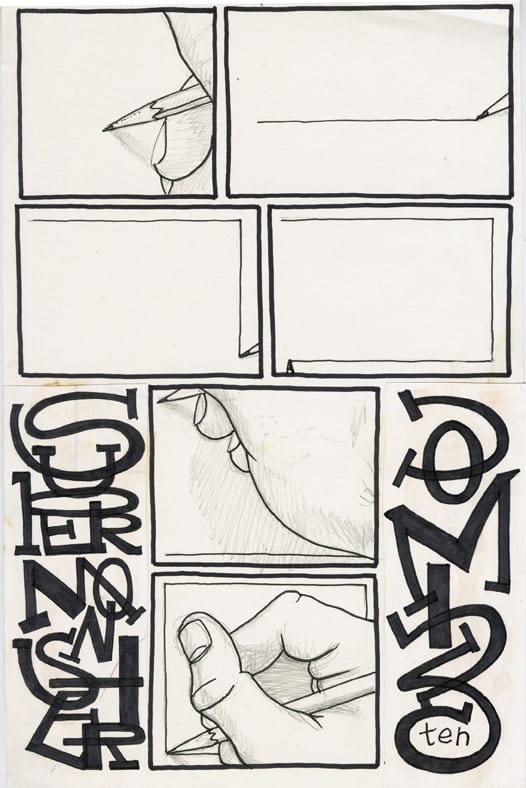

No, but I was a reader. As a kid, everyone was like, “Oh, Kevin’s into books.” When we would go on vacation I was always reading the whole time. I was into science fiction and fantasy, and then Stephen King and so on, but I don’t think I ever thought to myself that I would make my own stories until much later, when my friends and I were making up our own characters. I had done all these drawings of superheroes, but suddenly there was a point at which I sat down and drew a page of comics, and that was like a real leveling-up experience. I distinctly remember sitting at the desk and having this intense new feeling, like “I’m drawing a comics page.” I remember where the desk was and I remember sitting in the chair and everything. And obviously I’ve arranged my life around it ever since. I still have those pages, too. (laughs) I kept all that stuff. I found them recently and they’re not anything special to look at. I will say, though, that I was experimental with my layouts right from the beginning. (laughs)

So I think the point at which I started thinking about making up my own stories was exactly the same time I started drawing comics pages. It wasn’t like I already had this rich fantasy life that I just had to try to fit in the form of comics. It developed together. I didn’t think about writing until I started drawing and reading comics, and then that was it.

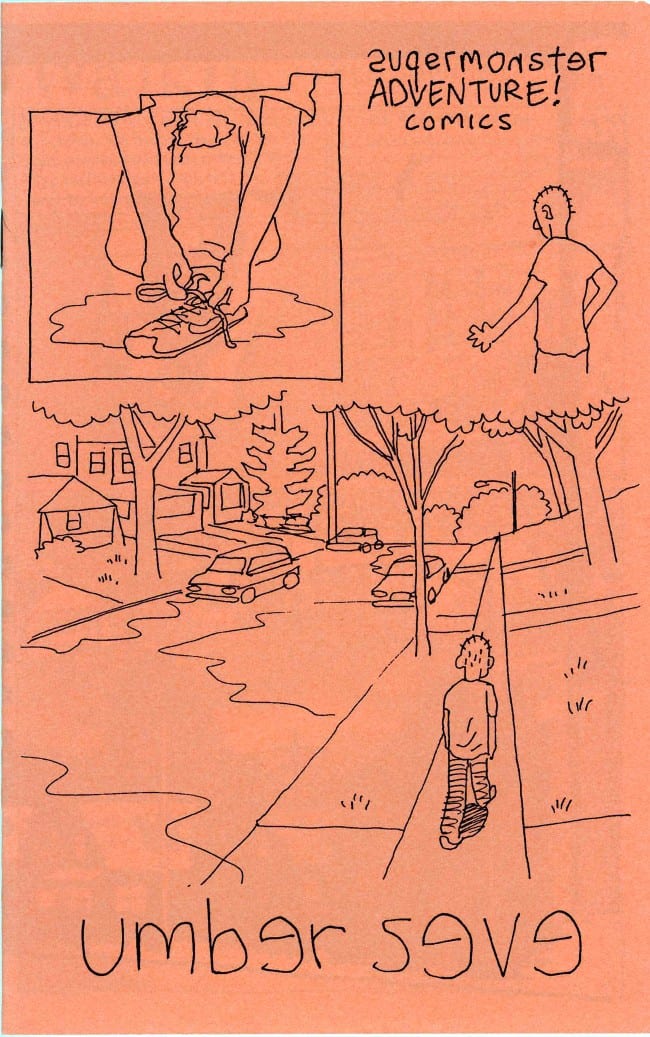

So is this what eventually turned into Supermonster?

My friends and I did comics and printed a few, and then later on that series got renamed Supermonster, the name of one of my characters. Eventually I took over the whole thing and did it all myself because, at that point, my friends were not really interested in drawing comics anymore, but I kept going. I kept doing it all through college and then hooked up with John Porcellino’s catalog, Spit and a Half, and that was a big encouragement for me.

He distributed your minis?

Yeah. When I was in high school, I started reading minicomics because the store that I went to had a mini-comics spinner rack. At the time I just bought whatever comics looked interesting to me, I was hungry for any kind of comic book. So I read King-Cat and Optic Nerve and… I don’t know where this store was getting them, maybe through Wow Cool or something? I think that was around back then. I don’t know. There were also different Chicago minicomics and ‘zines, like Silly Daddy, that ended up in that spinner rack, and they also had West Coast stuff, like Destroy All Comics, Jeff Levine’s ‘zine. I remember reading that magazine in high school study hall and reading reviews of mini-comics by Tom Hart and Jon Lewis and thinking, “Wow, I have to order these.” That was an exciting new world for me, ordering minicomics and the whole world of ‘zines.

Up to that point I didn’t even think of myself as being part of that world. Those guys were like celebrities to me. (laughs) But once John P. carried my comic in the catalog, I started thinking maybe I could find a place in the exciting world of alternative comics.

I also got interested in King-Cat and Optic Nerve as a specific way of doing comics, focusing on everyday life and autobiographical stuff, but also free and easy. You could do a comic of something that happened to you or a dream or you could do something abstract, whatever. That was more exciting to me than doing a fantasy epic, or a superhero story, or whatever. My tastes started to change. The idea that you could do an actual comic series and fill it with whatever real life stuff you were interested in or whatever weird stuff happened to you, or just play around with whatever ideas you had, from issue to issue, that model seemed so perfect to me that I thought, “This is what I’m going to do.”

How many issues of Supermonster did you end up putting out?

Well, it’s hard to count because it changed a couple of times. I guess in the teens. The issue that became Gloriana was #14, but I think that was maybe volume two? It’s hard to say exactly, but it doesn’t matter.

Do you have any sense of who your audience was?

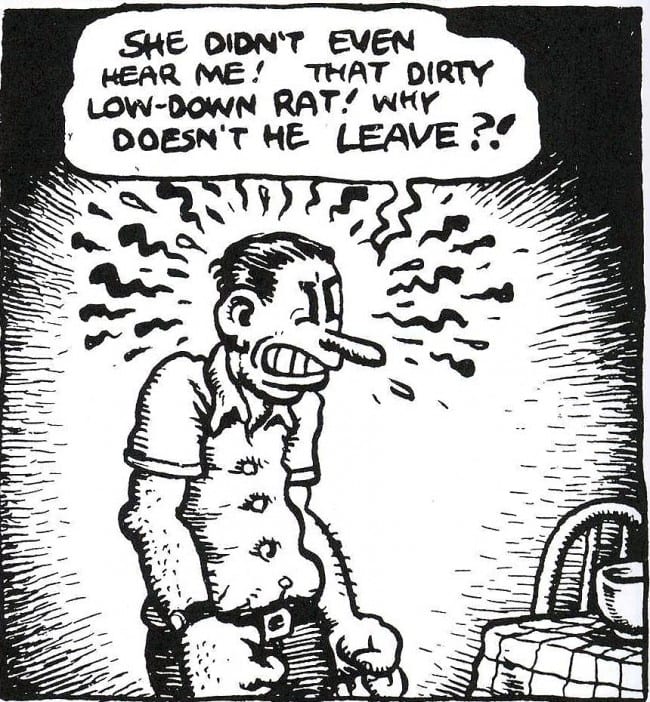

I have no idea. I didn’t even think that there was an audience. I got some nice letters from people, and I got encouragement from other cartoonists, but I was doing weird experimental stuff, and I wasn’t really sure of what I was doing yet. I didn’t know what I was doing. It was a lot of weird stuff and I knew no one was going to get really enthusiastic about it. Like I was doing comics that were based on Calvin and Hobbes but were trying to be ironic and sad like Chris Ware. Then at one point I got into Crumb and I was thinking I needed to try to draw like him, so I tried to draw this adaptation of The Doors’ song "The End" in the style of underground comics. It was all psychedelic and stuff. (laughs) It’s embarrassing to think about now. I haven’t looked at it in years because it’s very embarrassing. I was trying to figure out how to draw and what I was interested in. I was young and I didn’t really have any interesting ideas, so I’m grateful that John took my comic and put it in the catalog, but I’m also happy to have that work lost and behind me. Being in the John P. catalog was a huge deal for me, that encouragement.

You said you got some encouraging letters. Who did you hear from?

I remember getting a nice letter from Dylan Williams back in college that meant a lot to me. There was advice in that letter that I still think about. Not necessarily because it was great advice as much as that it came at a time when I couldn’t believe that a guy I knew from Destroy All Comics would be giving me advice in a letter. He was even critiquing the way I drew hands. He was like, “People judge your work based on how good your hands and feet look, so you want to make sure your hands and feet look acceptable enough.” It was something like that.

You’ve just gotta go look at a lot of old Ditko.

Once you figure it out, they’re not that hard, but up until that point they’re hard.

You produced these books entirely by yourself? Not just the drawing and writing, but you were printing, folding, stapling, and mailing everything yourself, too?

Yeah, in college I would Xerox them at the copy shop on campus. Back in high school we wouldn’t go to a real copy shop, we would use the copier in the grocery store. The thing was, we didn’t make our own comics and staple them together because we had seen anyone else do it, we just figured it out on our own. Then we found out later that all these other people were doing it, too, making ‘zines and mini-comics. For me, there was a feeling of synchronicity where it was like, what we’re doing fits together with what these other people are doing, so of course it’s the direction I should keep going. I knew already at that point that this was not a thing you made a career out of, it was just something you did, like you had a day job, and you just did comics because you couldn’t not do it. For me, it was like, “OK, I’m like them. I have… whatever force causes them to do their mini-comics, I have the same thing in me.”

I started out far from DIY or punk culture in a pretty square suburban Christian environment. I was still too afraid, too much of a square Christian kid to feel like I ever would fit in with the punks and the artist types. I was in-between. I still feel that way. But I naturally gravitated to the people who were making their own mini-comics and ‘zines because that was what I was also obsessed with. Whereas I played countless hours of baseball and basketball and soccer growing up but I never enjoyed that or felt connected to it. In sports I never felt, "These are my people." It was always like, "I hope it rains today so the game is cancelled. Please rain today." (laughs) So once I had a chance to stop playing sports, I was done with that.

“I’m so glad that’s not me saying that.”

Speaking of baseball, I did a really unusual interview with an artist several years ago named Brian Allen McCall. I’m sure you never heard of him.

No.

He did very small number of comics in Heavy Metal in the mid-‘80s, but he was also briefly a Major League Baseball player.

That’s crazy!

Yeah, and it was very interesting hearing him talk about baseball. He made it all the way to the majors, and even hit two home runs in a game, yet he still felt like art was his true calling.

Do you think that guy is still alive?

He’s definitely still alive. I see his stuff online. He has a Flickr account.

There was a piece in the online New Yorker recently about another guy who was a professional baseball player who had quit to become a writer, and at one point he said something like, “I feel like I’ve wasted so many hours on baseball that I should have been putting toward writing,” and when I read that I had this feeling like, “I’m so glad that’s not me saying that.” Because there was a point at which, I don’t know how great of a baseball player I was, but I was good enough that I was getting scouted by big colleges in high school and winning tournaments and getting MVP, stuff like that. The plan was, I was supposed to play baseball in college and get a scholarship. The idea of saving all that money appealed to me as a Dutchman. But in the back of my mind I was always thinking, “I’m going to have to be a baseball player and somehow still find time to draw comics.” I knew that was not going to work.

It’s funny, that stubbornness is really kind of ridiculous, and it’s very impractical too. I’m finding this out as I’m getting older, and poorer. I’ve just always had this stubbornness that comics are what I’m going to focus on and the rest of it will have to work itself out somehow.

Were your parents supportive of you doing comics?

You know, I don’t think so, but it never got ugly or anything. They were pretty tolerant of it, really. I think they could see how into it I was. The title Supermonster actually came from my dad at one point saying something dismissive about comics, like “You’re always in the basement drawing those ‘super monsters,’ you should go outside and get some sun,” and I thought it was such a weird thing for my dad to say. I’d never heard of that word before. So that’s why I named my series Supermonster, which I see now was maybe kind of a hostile thing to do, under the surface. (laughs)

When did you give up playing baseball?

Well, I stopped playing sports because I slowly realized I had no interest in it, but I also conveniently had an injury in high school that took me out of the second half of my senior season, and then it was like, “This is my chance.” I must have had a talk with my parents, but I have no specific memories of that talk. I’m sure I just seemed to them like a dumb teenager who didn’t really understand the gravity of what I was saying, but I just told them, “I don’t want to play sports anymore.”

I think going to that Christian college was kind of my way of compromising, or my way of saying “I’m not going to go to a big school to play baseball but look, I’m gonna give my life to God and the Church and be a minister,” you know?

Like you were appeasing them in some way?

Yeah. I don’t think I admitted that to myself at the time, but feelings like that were definitely in the mix. I wanted to be a good kid.

“Comics became almost like an engineering problem.”

So did you roll from Supermonster right into the D&Q Showcase?

Well, there was “Green Tea” in Orchid, but I think soon after that was “28th Street”. John P. did another great thing for me in college, which was one year he wrote me a letter and said that he liked Supermonster #7 and that he couldn’t use his table at SPX that year, and would I want to use it? That letter was mind-blowing to me because I didn’t know John that well, and it was out of the blue and because it felt like validation. It was more than just “hey I liked your comic.” I would never have thought about going to SPX. That was beyond what seemed possible to me in my narrow conception of what I was doing. I told my roommate, who I also should give a ton of credit to, about John P.’s offer and he was like, “Hey, we’ll drive out there. It sounds awesome. Let’s go.” So we drove out to Washington DC for SPX in ’98 and that was great to see everything and to meet people, and after that I was like, ‘I’ve got to go to these shows now.’

So years later at APE I went around at the end of the show and gave leftover copies of Supermonster #14 to people, and I gave one to Chris Oliveros, and he wrote to me about doing something for what used to be called the Drawn and Quarterly Showcase. That was ten years ago this year. I was thinking about that earlier this week. So that felt like my next level-up.

Did that feel like you’d arrived?

Well, it was being published by someone else. That was a very exciting time in my life. I was in St. Louis and working at the museum, but also working on my stories for Showcase at night in the basement of my apartment building. I would go down there and try to figure out the story. It was fun. I felt a lot of pressure to do good, obviously, but Gloriana also gave me a lot of confidence. I felt like I was free to do weird things with comics.

What kind of things?

I started trying to make these suites of stories where I took everything I was interested in, or thought would make a good comic, and put it all into a mix, and arranged it in a formal way or a musical way that felt to me like it worked together.

You talked in a couple of interviews about thinking about comics in terms of music. Is that something that’s behind the scenes when you approach a page or a story?

Yeah. I’m not trained in music, and I don’t have any deep knowledge about music theory or anything, but for me the idea about comics and music came from an interview that was in Destroy All Comics, where Dylan Williams interviewed Chris Ware. That was the first time I read Chris talk about how ragtime influenced his comics, and how he thinks about rhythm and music. How the big panels are like heavy chords and the small panels are like speedy sections. It’s interesting to me to think about comics as having rhythms and tones. I guess you could also think about them as having different interweaving melodies. I read that interview in high school and it really stuck with me. I suppose it’s a metaphor that is also used to talk about literature and movies, things that flow, but it was the first time the idea entered my head.

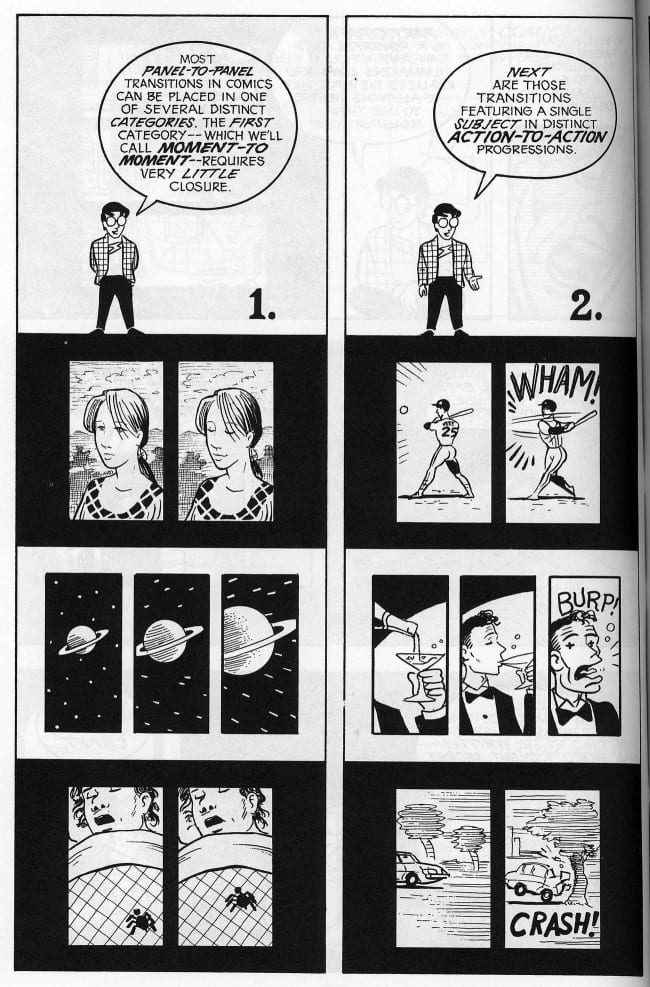

The other thing that I read in high school that was a huge influence on me - and I was thinking about this today and have been thinking about it lately - is Understanding Comics. That was the book that got me starting to think about comics in a formal way, as opposed to just focusing on the content of the story. I really think interest in that book needs to come back around again. It was kind of big deal and then it faded away and now people don’t really talk about it that much anymore. I mean, it has problems, sure, but still there’s a lot in there that was eye-opening. Though I haven’t looked at it in a long time.

What was it that resonated with you from that book?

He talked about the form and then he showed you these things happening on the page. It felt mystical, like space opening up. In the back of my mind I still think about a lot of stuff from that book when I approach a page. I became aware of the strangeness of panels, and of panel to panel transitions, and space and time, and the page, all that. I saw so many more things going on. I think before that book it was like, "Comics have cool drawings and cool stories, and you can get lost in a good story, and wouldn’t it be cool if you could imagine yourself in this fantasy scenario?" But after reading that book, comics expanded out to… I almost want to say engineering, which sounds dry and boring, but comics became almost like an engineering problem, or an architectural problem. I think there was always a dormant part of my personality that was looking for something like math or puzzles to get lost in and play around with, but I wasn’t into math or puzzles, so I found it in comics.

It was also Understanding Comics that first got me thinking that comics is this really complex form for communicating and representing life, moment to moment and the structure of experience. I’m still fascinated by how comics work.

“Fight or Run is my game design.”

Switching gears, I realize we haven’t even talked about Glenn Ganges at all.

Oh yeah. (laughs)

You’ve said in a number of interviews that he’s not an autobiographical character or a reflection of your personality. I’ve always thought of him as Flakey Foont.

I guess he looks like Flakey Foont. Sometimes I draw his eyes too big or his nose wrong and think, “That’s not right, that’s Flakey Foont.” (laughs)

Is that a conscious thing or just a coincidence?

No, it’s just a coincidence. What it really is I think is that both of us are trying to draw like the classic American newspaper comic style.

Like Frank King? That style?

That era, yeah.

Who would you say represents that style? George McManus?

Yeah, all those guys. Stuff like The Gumps. It’s a generic way of drawing a human face. In my original idea for Glenn, he was just this generic guy. Around that time, in college reading the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comic Strips, the styles in there made me think, "This is a nice standard vernacular style." It doesn’t have anything flashy about it, it was just a classic comic strip style.

You’ve stuck with Glenn longer than any of your other characters, even though he’s not a character in a psychological sense. Why do you keep going back to him?

At some point I realized that a smart artist doesn’t reinvent the wheel every time. It’s a dialectic process, moving forward. You’re mixing the known and the unknown to make new work. I was never that interested in making up new characters. Sometimes I’ll need a bit player so I have to design someone. I’m not interested in this person as a character, but I need a guy in a suit to come and talk to these people, so I guess I’ll figure out what this guy should look like. It’s not like the Hernandez brothers where they probably have the same thing happen initially, but then later they’ll be like, “That guy in that suit that I made up, what’s his deal? What was he like as a child, and what’s his family like, and what happened to him in the ‘80s?” and stuff like that. That’s cool and interesting to me too, but my work doesn’t end up going that way.

And in the same way that I stick with Glenn Ganges, in Ganges, the series, I’ve stuck with the same night, because I’m more interested in telling the same story over and over in different ways than I am in telling different stories, if that makes sense. Once I had the idea that Glenn would be awake at night and wouldn’t be able to sleep, I thought, “Hey, I could do stories about that forever.” I thought of many possibilities. Whereas, thinking about Glenn having many different complicated experiences and having a large cast of characters, and having to balance a bunch of things like that seems too difficult and doesn’t seem as interesting to me.

I think if I stick with one character, and one limited milieu, it also balances out the variety of formal hijinks that I would want to try. Like, let’s try going into his mind for a while and see what it’s like in there, or let’s try playing it backwards, or making the story into a circle. In Glenn’s memories or fantasies I could also go in other directions if I wanted, but I would always anchor it all in that one night, at least with this series.

In Ganges, you have a lot of video-game-inspired art, especially in the second issue, but also in Fight and Run and other stories. Where does that influence come from? Are you a video game enthusiast?

Yeah, but it’s never been a real dominant thing in my life. Ever since we had a Tandy back in the day I always was into games. That was a Radio Shack computer with a 256k hard drive. I’ve never wallowed in gaming like some people, all day, day after day. Real gamers spend their money and put their time in. For me, it’s a guilty pleasure, a few hours a week.

Though for a long time I played this game almost every night called Team Fortress 2 on Xbox. It’s a game where you play in teams, and you can talk to other people on the microphone and work together. That was a big part of my life in 2012. There was a whole crew of people that I played with. It got to be like going to the neighborhood bar and seeing the regulars. I was logging on and playing the game every night and talking to the same people every night, then we’d play the game for a little bit and go to bed. It was a lot of fun. But that was not a good way to end the day, playing a game late into the morning, and stressing the body and mind. You don’t sleep well, you stay up too late. It wasn’t healthy at all. But it was fun and I had a good time.

The Ganges #2 story specifically was when I worked at Xplane and we played a lot of Quake after hours. Do you know that game?

I don’t, but is that the game you represented in the story?

Yeah. I called it “Pulverize” and in the comic it’s a mix of Quake and another game called Unreal. This was before Xbox 360 and online console gaming. We would play it on a local network in the building with other employees after hours. I had moved to this strange city where I barely knew anybody and this job was very stressful. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing during the day, so it was such a joy at night to forget about everything and play this game. This was 2000. A lot of that went into issue two, that sense that this is a ridiculous thing to spend so much time doing, but the real attraction was being with other people and having fun, joking around and using the game as an environment to do stupid things or pull off an awesome move and then feeling like a legendary moment just happened. That’s true of the Internet in general, I think.

So it sounds like it’s just purely for entertainment, as opposed to looking at it from a design and artistic sense?

Yeah. Of course I can’t help but do that, but I know real gamers and that’s a big thing for them, whereas for me it’s only a side interest. Fight or Run is my game design. There’s just not enough time for everything. Now if ever I play for like a few hours in a day I can feel my body getting tense and stressed out. It’s not relaxing to play video games.

“I chickened out, and I’ll always regret that.”

I had a few follow-up questions based on your conversation with Gary Groth and Art Spiegelman in the Comics Journal #300.

I was just thinking of that interview. The first thing I always think about is that Gary asked if I wanted to do the cover for it and I chickened out, and I always regret that. Sometimes I look at the other big issues of The Comics Journal and how, I don’t remember the numbers, but like Jaime Hernandez did #150 or something, and then Ware did #200, and Gary Panter did #250, so I always think, I could have been part of that series, which would be crazy. Probably right that it didn't happen. At the time I don’t think I could have pulled it off. In those days I would get assignments and then panic for weeks. Nowadays I think I could do it.

One of the things that stuck out to me from that conversation was that you said you come to comics thinking like a writer as opposed to an artist. Can you elaborate on that?

I guess I meant I’m more interested in abstract things like words and stories than in actually drawing. I don’t know if that’s the right way to say it. I’m assuming that the opposite of what I’m talking about would be a person who already has images and colors in their mind and things grow organically from that as they draw. They compulsively make images. I’m not a compulsive drawer. Or I imagine someone who is inspired by a kind of visual experience, and so they draw a comic that looks the way they want, like cartoony or realistic or busy or something. Whereas I feel more at home in concepts or words, and the drawing serves those ideas. I don’t know. I want the imagery to be pretty transparent, generic and readable. It comes second. It’s more like an engineering problem than an organic expression of my taste for a certain kind of visual experience. I guess that’s what I meant. To be honest it’s not that clear cut to me anymore.

In that interview, you also mentioned something you called “empty formalism.” What did you mean by that?

Yeah… I think what I meant was dry formalism, or solipsism. It’s impossible to have empty formalism. (laughs) Every form has to have some kind of content, and every content has some kind of form, so there’s no such thing as empty formalism, but I think maybe there’s cold formalism, where it’s too uninterested in making contact with the reader.

You mean like it takes the reader too far out of the narrative to the point of distraction?

Yeah. It’s just a matter of taste, but I think the kind of work that I want to do, or that I think is going to be the most successful keeps in mind that the reader needs to have a good sense of what’s going on. That’s not to say there’s not a place for far out experimental comics. I’m fine with that, but my interest is not to do something that is totally bewildering to people.

I feel like to be effective with the reader you need to surprise them with the formalism. You need to give them what they’re expecting and then gently introduce something that’s different, and then you can gradually blow their mind, (laughs) instead of just tossing a bunch of mysterious lines at the reader or whatever. I’ll always give the artist the benefit of the doubt that there’s probably something smart going on, but if I don’t know what’s going on, then, for me, it’s not successful, it’s not inspiring. But I don’t think it was right to call that “empty.” I am interested in a lot of formalist work. I could easily see myself making even weirder, unreadable comics, and I guess I’ve dabbled in that, but I’m really afraid of going too far down that road. I’m sure we would both get lost. For some cartoonists that’s what they want to do and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. Also, once I finally understand what they’re actually doing I’m usually like, “Oh this is pretty brilliant.”

Are you thinking of something in particular?

There’s some younger cartoonists who do difficult work, and I think it’s smart stuff, but as a reader sometimes I need some help to get up to speed. (laughs) I’m not afraid to say that I don’t really get this. I wrote Dash Shaw an email years and years ago and I was like, ‘I don’t really understand this book.’ It was one of his older, really weird comics. His newer stuff is less opaque, I think. I said, ‘I don’t understand this.’ I think he took it to be that I was putting it down, but I was really saying “No, I need help understanding what is going on.”

And I’ve had that happen sometimes too.

You’ve had people react to your work that way?

Usually if they do, they don’t take the time to tell me, but I did have a guy write me a letter about Wild Kingdom and he said, "I’m sorry, I just do not understand this book… I don’t even understand why anyone would make a book like this. I’m just wondering if you can explain it in terms I can understand and maybe I can appreciate it." I thought it was brave and wonderful that the guy wrote me a letter about it.

Did you respond?

I tried to explain about the irony of using the forms of a nature documentary and the packaging of a science textbook, which are forms that we use to map the world in a comprehensible way and feel comfortable and understand things, and that at the same time the book was also about a sort of panic attack happening to this character who is interacting with nature in a strange and terrifying way. So I was like, it’s those things mixed together. (laughs) Then I said how all the commercials are mixed in because it’s a nature documentary, and commercials are normal human world stuff, but if you’re in the state of mind where you feel a little panicked and insane, they can seem crazy and monstrous too. If you’re in that state of dread already, the world warps around that. And I hope it was funny too of course, and there’s more stuff going on too, I hope.

He didn’t write me back, so (laughs) I don’t know if that was effective. Normally I don’t like to explain my work in public like that because I feel like it should speak for itself, but as I’m getting older I’m realizing more and more that I need to also explain things. It helps me when other people explain their work, but what I don’t want is to give the impression that “OK, there you have it.” Like it was an equation or a puzzle, and the solution is this and that’s all there is to it, you don’t need to read it.

You don’t want to undermine it.

You don’t want it to die or to oversimplify it. You make art because you want an infinite richness on many levels, like a living thing. You want symbols to echo off each other in more complex ways than you can just describe in an explanation or a plot summary. And you keep making work because hopefully new work sheds light on old work, and you keep moving forward instead of stopping to explain yourself. But, like I said, I’m mellowing on that a bit.

“I have a big pet peeve about the classic approach to non-fiction comics.”

You’ve been doing more non-fiction work recently, and you’ve done that off and on with adaptations of different things over the years, but is that something you’d like to do more of?

Yeah, I’m really interested in non-fiction comics. One of my dream projects would be to do straight-up non-fiction about different topics I’m interested in.

What’s an example?

Well, a lot of it would be about different philosophical ideas, or like how the brain works. Drawing and diagramming it would make it more concrete, less abstract, and hopefully easier to understand. There’s certain classic philosophy texts that I would like to do comics versions of. I feel like there’s so much visual or diagrammatic activity going on in the text that you’re being asked to do in your head. It could either be diagrammatic or it could be anecdotal, with Glenn walking around. I often come across something when I’m reading and it’s like, I’d like to work this into my comics. I can see how to make it into comics. Sometimes my stories can end up feeling like non-fiction in the sense that it’s not dramatic, it’s an explanation of something.

Are there any non-fiction comics that stand out for you?

Well, I have a big pet peeve about the classic approach to non-fiction comics, which I call “the slideshow.” It’s just text, illustration, text, illustration, text, illustration, and I don’t feel like that takes advantage of comics. Worse than that though, it’s inefficient. The standard comics page has evolved to tell a certain kind of story, and it looks the way it does because it’s used for anecdotal storytelling. But if you’re going to do a complex non-fiction comic, you probably need a different ratio of text and image than you get with a classic comics page. Your classic comic page is much more heavily skewed toward image than text. Everybody, especially cartoonists, hate it when there’s too much text in a panel, and I agree that ultimately there should be some kind of balance, but I think if you’re going to do good non-fiction work, and it’s not going to be just for young readers or a comic book for teenagers, then you’re going to have to skew it so that there’s more text. There just has to be more text because non-fiction generally has a greater density of information. So you’re going to have to have blocks of text sometimes and then some supporting images to clarify and enrich the information. You have to be more creative with the mixing of image and text so that sometimes it might look like a classic comics page, but other times it might look like a page of prose with illustrations and diagrams.

Is Joe Sacco’s work a good example of what you’re talking about?

Well, he’s great at what he does, but even he still approaches it like a classic comics page. It’s not a slideshow, it’s more like a documentary, and it’s great. The storytelling is along the lines of what you’d get in an in-depth magazine article, I guess, with maybe a bit less density of information. There’s that book he did with Chris Hedges [Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt], now that had much more of a mix of text and image. I feel like if you’re going to do a non-fiction book and it’s not just going to be a simplistic, heavily compressed approach to the topic, if it’s going to a book for adults or experts in the field, and it is going to thoroughly treat its subject, it’s going to need to have a different balance of text and image. And if your average comics fan is like “Oh, there’s too much text,” that’s fine because the book’s not for them. It’s not like a comic book that’s for anyone interested in comics, it’s a non-fiction book that takes advantage of the powers of comics and illustrations.

I guess comics is used as a way to bring in more readers to a topic, to popularize it, but I want to see comics used as a way to bring more light to a topic for readers that are already experts in that area, already deep into it. To me, that’s a much more interesting way to go than the route where every other sentence gets illustrated in a panel, and every page looks like a standard comics page. I just think there are more possibilities than just using comics for casual readers, or all text with no images for advanced readers.

Can you think of other examples of stuff like that which you’ve read? Remember those different literary figures books, like Crumb’s Kafka for Beginners?

Yeah, I think those are almost all terrible. A visual guide to whatever. Actually I haven’t read any of them but just glancing at them I can tell that they’re terrible. Anyways the whole point is that they are for beginners. Pictures are for beginners, no-pictures are for grownups. The Crumb book was great because it had comics, and it was Crumb, one of the greatest cartoonists ever. But it also had some text in it. Sometimes you’ve just got to dump a bunch of information and the most efficient way to do that is in text. Sometimes text struggles to describe something that could be easily understood in a diagram or sequence of comics panels.

All that being said, in Ganges #5 there are non-fiction sections, but I use the usual 8-panel grid, and my page count was limited, so don’t look there for me practicing what I preach. I mean, I hope it’s more interesting than the straightforward slideshow approach, but it wasn’t the time or place for what I’m talking about here. The non-fiction in Ganges is more allegorical than it is straight up non-fiction.

“I hadn’t felt that simple joy of just drawing comics in a long time.”

Why did you decide to redraw the first issue of Kona and what was the experience like?

It was a great experience because for a couple weeks I didn’t do anything except redraw those pages, and there wasn’t much to think about. I hadn’t felt that simple joy of just drawing comics without thinking about it too much in a long time. I’d love to do much more of that but there’s just not enough time. I have so many ideas for things.

Was there a reason you chose that particular issue of Kona?

Well, ideally I would redraw the entire first ten issues. That’s a great run of a crazy comic. Jason Miles turned me on to it, but I guess everybody knows about it. They’re great. For me it’s not the art so much as the writing. The writing is crazy. The art is crazy and great, too, but I feel like the writing should get more attention. I feel that way about a lot of old comics.

Who was the writer?

That’s a whole mystery because he wasn’t credited and for a long time nobody knew who it was. Now somebody thinks that they’ve established that it was this mystical rabbi in New York. It almost sounds too good to be true, like a comic book plot itself. I think they’ve got good evidence that it was this guy. Lionel Ziprin was his name. I haven’t checked into it too deeply.

But I feel like there’s a lot of love for the artists of old comics, but you don’t hear people talking much about the old writers. I mean, it’s complicated. There’s good writing and then there’s writing that is so crazy that’s it’s fun to read. It’s like with cult films, which can get tricky. But I think one way to point to some of that old comics writing is to redraw them in your own style so you take away the focus on the art but keep the weird writing.

Did you reproduce the writing exactly?

I fixed a couple things for the sake of reading, but that’s it. And like I said, the first ten issues are all awesome and it would be a dream project of mine to somehow draw all those, but it’s totally impractical. I have no time for that. Unless I could get paid good money for it somehow.

How was it copying the panels?

It was a good exercise. I changed around panels that I didn’t like. I think it helped me learn to draw hands and bodies better. I should do more of these. I’m working so hard on Ganges #5 right now and sometimes when I think about how little I can get done in a week it’s just depressing.

How many pages can you do in a week?

I shoot to get two pages done a week, but those are big dense pages. I can’t even really get two pages done, because I have Photoshop work to do for the second color, which has gotten more and more complicated. I’m trying out weird effects, and I get behind schedule.

“Coming up with funny sentences.”

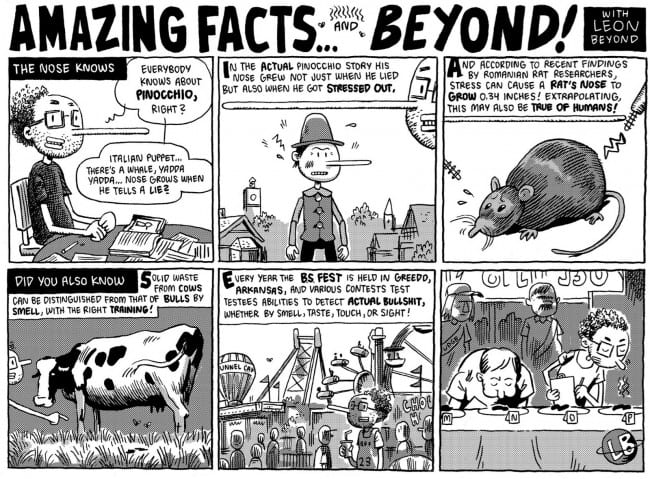

Are you still doing Leon Beyond?

No, that’s done. We’ve done a couple little strips here and there but it’s done.

How did you get started with that strip?

There’s different versions of this story (laughs) but the art director for the Riverfront Times approached Dan Zettwoch about us doing a strip because a couple times Dan and Ted and I did comics for them as USS Catastrophe and he was like, ‘Why doesn’t USS Catastrophe do a regular strip for us?’ So we were like, ‘All right, we’ll do it,’ and we batted around ideas and fake facts came up as a good idea. I think it was Dan’s idea. Dan also said he liked the word “beyond” and he wanted to work that in there, so Amazing Facts and Beyond was the obvious title.

Originally we were all going to try to do it, but Ted was too busy to do it very often, so it ended up just being me and Dan alternating weeks.

Was it a collaboration or did you each do your own?

We decided it would not be a good idea to have it be a continuing story because then we’d have to pay attention to what the other guy was doing. It worked well. I mean, like any comic strip or anything that appears in the paper every week, it’s going to have its ups and downs, because you have deadlines, so sometimes it turns out great and sometimes you’re cranking something out for the deadline and it’s not your best work. But I’m really proud of the work that we did, though I understand that it’s a lot to read. The book is very dense. It’s hard to read a lot of it at once. (laughs)

I don’t recommend that. I read a few a day.

Yeah, you gotta do that.

I think most comic strips are better that way.

Yeah.

With all the deluxe repackaging now… I would never suggest someone sit down and read The Complete Calvin and Hobbes cover to cover.

No, it’s gotta be like a ritual where you read a couple strips a day and then you go about your life.

Can you walk me through how you approached the typical Leon Beyond strip?

Well, (laughs) usually I‘d have some kind of idea about some weird thing about life and then I’d come up with some fake facts about it. Dan would do research on his. I think some of his are pretty close to reality, but with more jokes and puns. I almost never did research for any of my strips. (laughs) Maybe one Google search for a weird name or photo reference or something. I knew most of the time I did a strip it would be six panels, so usually I sat down and tried to write six panels and then draw them.

A lot of them were very tongue-in-cheek.

It got to be where the appeal of doing the strip for me was coming up with funny sentences. Funny to me.

What was your reason for publishing with Uncivilized Books?

Well, to be honest, Tom [Kaczynski] asked.

That was it?

And he’s a friend and it was a good deal. Dan and I were not in a big hurry to do all the work on the collection because we had other things going on, but once Tom asked, we got to work. It took forever to do.

Did you guys do all the design work yourselves?

Yeah. Between me and Dan, we pretty much did the whole book, but Tom helped too.

“I had a weird experience this year writing Ganges #5.”

You mentioned before that this year has been a big year in terms of your artistic development. What’s changed?

Well, one thing is that I finally think I’ve gotten better at drawing. A bunch of things clicked that it’s taken me so long to figure out. I didn’t feel like I was progressing very much until lately. I have not had a lot of good training or instruction, and I’m kind of a slow learner, but this year I realized how to draw better, and so I can approach things more confidently. Finally! (laughs) When I look at a drawing now, I can see it taking shape as I’m drawing it in a way that was trial-and-error before until it looked ok. But I feel much more confident than I have in years.

Was it a cognitive shift or…?

Yeah, I think of it like being able to see in 2D and 3D at the same time. I mean, it’s still not easy or anything, and I’m not saying I’m great at it, but there was something that clicked, after all these years! (laughs) I also feel like this year a lot of things have opened up in my understanding of my work, and my understanding of things in general. I’m more excited now than ever to do more work. I feel like I have a better sense of what I’m doing, and what my strengths are. A lot of the struggle with what to do with a blank page is not there anymore. I know how to get from zero to a finished comic without a lot of unnecessary confusion. I can put my energy into areas that are interesting to me.

I also have a better sense now of how to come up with ideas. I have a better sense of simple forms, like light and shadow. Not just drawing light and shadow, but the idea that every concept has a flip side, and how to use that as a way to approach the work. If your work is about something having to do with something light, for instance, then you should also pay attention to the dark part of it, that kind of thing.

That sounds like a Buddhist perspective.

Yeah, I just feel much more at ease where before it all seemed like a hodgepodge of gluing things together and hoping things would work and being anxious all the time. Now I feel like I have a much more organic sense of what I’m doing. I feel much more at peace with the whole situation now. I don’t know what it is, it’s just the culmination of a few years worth of thinking it through, and getting older, and it’s all come together.

I had a weird experience this year writing Ganges #5. I had been putting it off for years because I didn’t really know how to end the series. So I sat down and re-read Ganges #1 through #4 and I had this strange experience of seeing into my own work things I hadn’t seen before. I felt like I understood things that were going on in Ganges #1 through #4 that I don’t know if I consciously understood I was doing. I had this realization that if I just pay attention to the formal aspects of the work, I can see how to carry it forward. I always approach my comics with a kind of formal logic - what formally makes sense, finding a balance - and I found that if I looked at issues 1-4 and tried to find out what formal logic was at work, it made sense to me what I needed to do next. I had a bunch of ideas already, but I finally understood the form that those ideas should take.

It’s as if I saw that I had two points and a line, and then I saw that I didn’t need to continue the line, I needed to make a third point and then draw a triangle. And then a pyramid, and so on. I thought I just had these two things I didn’t know what to do with, but now I understand how to open up higher dimensions.

Which is not to say that I’ve got it all figured out, or anything like that. But I feel more excited about going forward, and really understanding it in a formal way has been key. Following the logic of the form. That helped me understand a new way to solve problems.

Can you elaborate on that? What do you mean by “the logic of the form?”

Like what I was saying before about light and dark—if you have something in the work that doesn’t have a shadow, metaphorically speaking that’s probably what it needs. If something has a shadow, then it becomes a more solid thing, and suddenly there’s space around it. And the shadow implies a light source, and so on. That’s like a metaphor for what I’m talking about. You think, “what is this thing’s opposite, or what would balance this thing? Then what balances that new balanced pair? What would open up space for new possibilities?”

Comics is full of problem-solving on many levels, and that can be very stressful. It’s fun work but it can wear you down. You can get mentally exhausted because you have to solve problems at the level of drawing, writing, page design, living your life, all these things. But seeing it all as a dialectic of forms that open up more space and more balance has helped a lot.

So you’re saying balance is a crucial part of your work?

Yeah. That’s one part of it. I’m still trying to figure out how to talk about it and not sound too crazy. You have to have someplace to start, and then where do you go next? It seems like the key for me to move forward is to think like this. It’s not a balance in the sense that it’s finished, because it’s always moving forward. I’m always thinking about creating new work, but the way to do that is to look at old work and then think, “OK, there’s this, so now what would open up a new space for new work?” You take what you already have and then you flip it, or mirror it, or make a shadow of it, or repeat it, or whatever, and then you notice that there’s also a new third thing, which is the space for the relationship between the first two things.” It’s hard to explain in words, it’s easier to diagram.

Speaking of diagramming, in other interviews you’ve talked about your background working with infographics, and you can really see that in the new Pocket Guides. Can you talk about that a little bit and how that’s influenced the way you think about conveying ideas formally?

Yeah. When I moved to St. Louis, I started working at Xplane...

What kind of business is that?

It’s a company where their clients come to them with problems that they want Xplane to represent in a clear visual way. A lot of times it was software companies with ideas who were just trying to get venture capital money for web sites, but other times it would be a big established company that needed to communicate with themselves.

Of course the best employee for a company like that would be a cartoonist, because you’re already used to thinking of visual storytelling, and comics are easy to read. It’s not a language that’s difficult, if you do it right. So working there introduced me to the idea of visual thinking and diagramming, which became very important for me in my work. I’ve thought about it a lot over the years.

I felt like the Pocket Guides almost moved beyond comics.

Well, yeah. I wouldn’t call those comics. There are little comics in there but those new books specifically are about things I’ve been interested in this year, like Buddhism and meditation. They’re my way of thinking on paper about those subjects in a jokey way.

I love self-help books, and there’s a bit of that in there, too. All you have to do is get yourself into a good mood, and then stay in that good mood. That’s all you have to do.

It sounds so simple.

Yeah. (laughs) You feel good about your good mood. (laughs) That sounds so stupid, but I think that really is a profound thing.

In other interviews you’ve implied that drawing is almost meditative for you. Do you think of it in those terms?

I don’t know. Now that I meditate for real, I don’t know if I would still say that. When you’re in the flow of drawing for its own sake, yeah. I think in any situation in life, what you hope to do is to get into a nice flow where you don’t have to strain, you don’t have to put a lot of effort into it, things just unfold one after another and you get a nice balanced flowing feeling. You have a sense of what’s going on, and you see the big picture and also have a moment-to-moment focus where it seems like, “I know what to do here” and you’re calm. I think the addiction people get for drawing is that feeling when it’s going like a nice flow. So yeah, I guess in that sense it’s meditative.

The problem is I’m usually drawing not for the flow or the fun of it, I’m usually drawing because I agreed with myself or someone else to get a comic done (laughs) so now I have to sit down and finish it. I also want people to like it, and to like me, so I’m working very hard to make it as good as I can. And I want to like it myself, too, so I want to make it as good as I can for my own sake. So for those reasons it can turn very quickly into something stressful. But hopefully you can put those things out of your mind and get into the flow of it.

“I feel compelled to put it out there.”

Over the years you’ve also done a number of things where you’ve taken your process notes, or brainstorms, or tips and shortcuts, and you’ve shared them with everybody either through mini-comics or online. Why do you do that?

It’s like a golden rule thing. It’s always interesting to me when other people do that, so therefore, I assume, other people might be interested when I do it. And it’s like, use the whole buffalo. I don’t do it as much as I would like to, because you don’t want talking about process to overtake actually doing the work. I’ve done so much thinking over the years about how to do this stuff that I feel like I could write a book, or I could write a ton of blog posts about it, but I have to do the comics, too, and there’s only so much time. I could easily turn into a person who’s always talking about my process, but when I have that impulse, I always have a counter-balancing thought that "you’re only thinking about your process right now to avoid working." (laughs) It can be a way to procrastinate.

I didn’t go to comics school or anything like that, so I really had to figure a lot of it out by myself. That knowledge feels hard fought and valuable to me, so sometimes I feel compelled to put it out there because I don’t want other people to have to fumble about like I did for years and then one day slap their foreheads, ‘Why don’t I just do it this way? Why did it take me so long to learn this?’

Have you ever thought about teaching or mentoring?

Yeah, I’d love to. I really have a love of that kind of thing where you’re like, let’s break this down and figure this out so we stop banging our heads against the wall. I like to do that for myself, and I’d love to have an opportunity to teach, but again, it’s a situation where the work comes first. Although, now that I’m getting older (laughs) I need to figure out a way to make more money. I’m thinking more and more that teaching would be a way where I think I would be very energized and intellectually challenged, and I imagine it would be personally rewarding more than going back into marketing or graphic design. But yeah, in the coming year, I’m going to have to start figuring out a way to make some money. (laughs) It’s funny that you bring up teaching and I turn it into a story about getting a paycheck, but that has been on my mind lately.

I’ve interviewed a few cartoonists who started teaching for that very reason and they ended up loving it because you also get the thrill of young, creative energy. Also there’s a lot to teach about comics, a lot of very specific things that students need to practice and understand.

Yeah, and it’s also a situation where I’m alone so much that I have all these ideas and I want to talk about them because they’re driving me crazy. I’ve thought a lot about comics, diagramming, visual storytelling, non-fiction comics, and all these things that my wife is sick of hearing about, and I need to find someone else to talk with about them. (laughs)

Do you keep up with much of what’s happening in the alternative comics scene, other than going to the shows?

I try to, but I feel out of it more than I used to. I try to order things online because I do feel a responsibility to try to keep up with the new stuff, but, and I think this is an inevitable thing about getting older, my own work has become both more interesting and more time-consuming. So even though I love to read comics, I’ll buy a book and I just won’t read it for like a year, whereas in the old days I would devour it right away. Nowadays I have to go on vacation to catch up on my comics reading.

At this point I have so many different things going that it’s hard to relax and just kill some time. Sometimes I feel stressed out and it’s like, the thing that I used to do for fun has turned into homework.

The trouble with me over the years has been trying to figure out how to balance working on comics all the time with having a healthy sense of normal fun, and other interests. (laughs) I’m always going too far one way or the other. I’m always working too hard on something and burning out, or trying to take a break from comics and then being miserable because I want to be working. So I’m always trying to find a balance. I’m lucky though to have a lot of time to myself.

You’re not doing any design work?

No. I really don’t do much freelance. My wife has been so understanding over the years about me focusing only on my own work, which hardly pays anything. Though money seeps in. As I get older, I have more things going on so little bits come in from here and there.

Your wife obviously supports you. What does she do?

She’s a librarian.

She’s cool with the arrangement?

Well, I mean she is, within reason. (laughs) I think my time is almost up. Anyone reading this who wants to hire me, please email me. (laughs) To be honest, it’s tricky as a freelancer because you can’t depend on any money for sure, so all the money that comes in seems almost miraculous. (laughs) Which is nice, in a way, because you don’t get used to it. On the other hand you feel like you’re poor all the time because you don’t have a steady income, so it’s hard to spend money. All you can really do is pay bills because you don’t know when the money’s coming in or not. It’s hard to think long term. My wife and I are getting pretty sick of that. So, after quite a few years of doing this, I am going to have to get serious about a more steady income.

Most cartoonists are in the same boat, as I’m sure you know.

Sometimes I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of what I hope to accomplish with my work, and I’m not too old yet. Hopefully I have a lot more time. I feel excited about finishing up Ganges, and also whatever comes next.