GROTH: What were you doing to earn money? You went from a garbage man to what?

WOODRING: I went from being a garbage man to being a cartoonist, basically. I drew some comics for Car-Toons magazine, which seemed like the big time to me in those days. I kept my expenses to a minimum and scrounged for cartooning jobs. That was the heyday of the faux-hippie business creep, and I met with a number of stoned middle-aged long-haired connivers who thought that if their tiny perspiring brains could only be harnessed to some stupid cartoonist the marketplace would surrender to them like a lovesick whore. I remember this one guy who had come up with an idea for a comic strip that he wanted my friend John and me to draw for him. We met him at his apartment and it was obvious from the get-go that this guy was probably a good man with an axe-handle but that he had no business messing around with ideas. He was a thug and he had one of his thug pals on hand to pretend that he worked for King Features Syndicate. It was like casting Arnold Schwarzenegger as Oscar Wilde. This guy's comic strip idea was a two-panel celebration of life's little close calls. For example, in one of them a big fat girl's boyfriend is dragging her onto a public scale; in the second panel the scale is broken and the girl is spared the humiliation. He had written literally a dozen of these things. He said to us, “Now the one thing I'm not going to tell you is the symbol I've got figured out to use at the top of this strip. It's an old symbol used to denote happiness and unhappiness on life's stage, and it's going to put this strip over the top. You'll never guess what it is, which is why I get 75% of any take, 'cause I thought of using this great symbol.” I said, “It's not the comedy and tragedy masks, is it?” There was a bad silence but the guy managed to control himself enough to mutter, “No.” Anyway, it didn't work out, like most of the work I tried to get in those days.

GROTH: Didn't you live in Seattle for a while around that time?

WOODRING: Well, in 1974 my mom died and I decided to get away from L.A. for a while and I moved to the woods near Everson, north of Bellingham. My friend Kevin and I rented a great little house in a bend of the South Pass Road.

GROTH: How did you survive? What did you live on?

WOODRING: We made some money by helping farmers get the hay in, or by doing other menial chores. I enjoyed that kind of thing because visiting the farmers and their families was an experience for a city kid like me. I remember this one farmwife who had decorated the house by placing glass jars of water with food coloring in them all around. It struck me as unutterably sad. I was also working for Car-Toons through the mail.

GROTH: Sounds pretty Spartan.

WOODRING: It was, it was. I lived on apples for a while because there was an orchard on the property. I saw a bear throwing up there once. I had practically nothing and lived on practically nothing and it was a great experience for me, the first time I had ever gotten away from the wreckage of my life so that I could look at it from afar and make some observations and choices before getting back into it.

GROTH: And how long did that last?

WOODRING: A couple of years.

GROTH: And you were constantly drawing?

WOODRING: Well ... sort of. I spent a lot of time just thinking.

GROTH: How did you teach yourself to draw? Are you entirely autodidactic?

WOODRING: Well, I didn't go to art school, and the art classes I attended in high school and junior college didn't do anything for me, but I've got the collected Famous Artists correspondence school material and I've learned a lot from that.

GROTH: You took the Famous Artists course?

WOODRING: No, I bought it used at a bookstore. Also, when I was an adolescent my best friend John Dorman and I drew comics all the time.

GROTH: This is the guy who persuaded you to work at Ruby-Spears.

WOODRING: Yes, but we're still friends. [Laughs.] He was, and is, an incredible natural cartoonist. All my life he has represented a standard of control and expressiveness which is allied to my own approach but beyond my reach. He did a drawing in our ninth-grade yearbook that was like a dagger in the guts to me because it was better than the work of many an adult practitioner and it was obvious that, of the two of us, he was the genius. We drew lots of comics together in high school and beyond; we called ourselves Barking Dog, and some of our work from those days is still around in some underground publications.

GROTH: Is he still working in animation?

WOODRING: Last I heard.

GROTH: When was that?

WOODRING: This morning.

GROTH: Doesn't it seem a shame to you that all these talented cartoonists you describe are working on this crap?

WOODRING: Everyone has their reasons. Obviously he feels differently about it than I do. It's frustrating to me to only be able to see his work in storyboards, though, and the world is missing out.

GROTH: So you two would draw cartoons together in your rooms.

WOODRING: Right. And egg each other on. That was a great thing for me, having a cartooning pal. I'm sure it had a lifelong effect on my work. I wish I could revisit those days and re-experience that fine, fine blend of energy, enthusiasm, and blissful ignorance. I used to love to look at my own work back then. Today it's a different story.

GROTH: What do you mean?

WOODRING: It's hard for me to look at my drawings, it's a painful experience for me to look at my stuff because I know what good drawing is, I've seen plenty of it, I've got lots of examples of good drawing in this house and when I look at my stuff it just looks like a collection of mistakes strung together with my own technique.

GROTH: Is that false modesty?

WOODRING: Of course not! I have high standards!

GROTH: When you say it's a series of mistakes, are you talking about it in a purely academic sense in terms of anatomy and perspective and formal techniques, or in some sort of artistic sense, mistakes of the imagination?

WOODRING: I'm talking about drawing mistakes, which as far as I'm concerned represent holes in knowledge or understanding. It's crucial for a draughtsman to put the viewer at ease with a display of mastery. A poorly foreshortened arm, a composition that draws the viewer's attention to the wrong area, a face that does not read ... these things are always embarrassments. It's frustrating for me because I've always felt, to borrow a phrase from Gil Kane, that I am a virtuoso yet I'm not doing virtuoso work. And when I see a great drawing, a drawing by T.S. Sullivant, one of his 10 or 12 greatest drawings, for me it's like looking at the pyramids or the Taj Mahal — it's such a wealth of beauty and of the love that a human being could have for the natural world and for the order of existence and for all good things in life that it can move me to tears, and it's such a great thing to be able to achieve that with a bottle of ink and a pen and a piece of paper. And I feel like I should know how to be able to do that. I feel like, just in my blood, like I am that kind of an artist, but I can't draw that way, I don't know how to draw that way, and it's a frustrating dichotomy. I always feel like I've had a stroke and amnesia at the same time — I can't function properly and I can't remember why, but I know I should be doing better.

GROTH: Do you think you've ever achieved that in any single composition or any single drawing?

WOODRING: Every so often I'll do a drawing that comes together in a way that I really like. But those things are rare. And usually they're using techniques and media that relatively easy to master. I can do charcoal drawings that I like a lot, but I feel that it's almost cheap — cheap when you're getting a psychological effect with charcoal, because you can almost do that without a pictorial thing, you can just make great shapes moving around and excite a person's mind. Pen and ink is much different, pen and ink for me is the ne plus ultra of drawing.

GROTH: What is it about a drawing that you look for? In other words, I don't think you're looking just for pure correctness of drawing because a perfectly correct drawing can be sterile and dull and unimaginative. It's far preferable to have something that's slightly less than perfect that's filled with some sort of imaginative virtues, but what do you consider those virtues to be?

WOODRING: Well, I guess oddly enough the thing that hits me the most and stays with me throughout the viewing of the picture is the composition of it. The less straightforward and more successful a composition is, the more amazing it is to me. And that's evidence of the artist who set himself a near impossible task, which is to approach a description of the world from the position of a real handicap. That's why I like Sullivant so much — he draws a lot of his main figures in three-quarter rear views. You can't see their faces. He puts all their personality in their posture. That's just astonishing to me, it's like those guys who write novels without using the letter “e.”

GROTH: If composition is that important to you, you must find drawing comics daunting, because in a comic you have four or five, six, seven, eight, nine compositions per page, plus the page itself is a composition. That's got to be incredibly intimidating.

WOODRING: It would be if I worried much about it, but I don’t because I know composition isn’t my strong suit, and while I greatly admire the compositional skills of others – Moebius comes immediately to mind — I don't hold myself to the same standards because I can get the effects I want without great composition. In a way, excessively skillful composition can obscure the grittier messages of a psychologically charged work. From a pure composition standpoint nobody's pages are better than Will Eisner's, but his work has very little emotional impact for me. Even his dramatic, overtly emotional stories don't hit me very hard, and I think part of the reason is that his composition is so perfect and graceful that his grim stories glide by sweetly like a mouthful of meringue. Evidence of a certain kind of artistic struggle makes a drawing more real, more precious to me. I have a drawing that Justin Green did years ago in his Binky Brown days, and it is so worked over and patched and re-worked and whited-out that it's just painful to look at because you can see all too plainly how hard he fought to achieve it — and this agonized-over quality works with the subject matter to amplify it to an extent that is almost viscerally affecting. When I first saw a T.S. Sullivant original, I was astonished to see that the whole surface of it was picked over and rubbed and peeled away, He would ink down a line and then he would peel the whole edge of it. When you see reproductions of his work they look like bad reproductions, but that's what they look like in person.

GROTH: What contemporary cartoonists do you stand in awe of? If there are any?

WOODRING: The Fantagraphics logrollers, of course. Pete Bagge is one of the ultimate greats. Dan Clowes is a great cartoonist. The Hernandez brothers defy comprehension as far as I'm concerned. I was listening to Jaime talk about how he draws and his total lack of need to use any reference for anything and it made me very unhappy.

GROTH: You couldn't get much farther apart from someone like Jaime and someone like Peter.

WOODRING: Except that they're both keen observers of and commentators on humanity. R. Crumb is the world's greatest living cartoonist, in my opinion. Justin Green is still my all-time favorite underground cartoonist.

GROTH: Even more than Crumb?

WOODRING: Yeah ... I think Crumb is a greater cartoonist, but I enjoy Justin's work more. He has access to a view of life that is deep and rare.

GROTH: Was Crumb a formative influence when you first got into undergrounds?

WOODRING: Oh yeah. In fact, I've had to fight hard not to imitate him slavishly. But there'd be no purpose, 'cause he's an open conduit and you can't imitate that. Just to be able to draw like that, that comfy-as-an-old-slipper way he has of drawing, and to be able to draw anything as he can, and to have a line that is so informed that it functions wherever you put it, like Picasso, I wish I had that guy's talent.

GROTH: Who else do you admire?

WOODRING: My current red-hot favorite is Rachel Ball, in England. She has work in the UK Deadline. When I look at her work my head just spins 'cause it's so monstrously appealing, sly and insinuating like a horse, slightly sloppy and eye-lickingly sweet. To top it off, Peter Kuper told me she's really beautiful.

GROTH: Made her more of a favorite?

WOODRING: Well, hearing that actually kind of brought me up short because now I feel like I can’t be such a rah-rah boy about her work because it might make me look ... I don’t know, suspect. Vile flattery. I'm also crazy about Mark Martin's work, and he keeps getting better and better. He's a great natural cartoonist. Working with him on Tantalizing Stories was great because ... well, because he's real easy to deal with, but also because his constantly accelerating rate of improvement spurred me on to improve my own work. Terry LaBan is great. Cud #4 is so good it makes me slightly ill. Chester Brown is a genius, of course. Joe Matt, Seth, both terrific, Charles Bums, Mack White, Wayno, Roy Tompkins ... Mark Newgarden ... Paul Mavrides ... ah, I'm forgetting a bunch of 'em.

GROTH: You like Kim Deitch?

WOODRING: Oh yeah, I love Kim Deitch's work, He's great.

GROTH: S. Clay Wilson?

WOODRING: Um ... I loved his early stuff, It seems to have gotten less poetic to me, which is what I liked about it. There was a huge amount of poetry in his Zap stuff ... Lester Gass and all that. The way his people would speak while conducting their necrophiliac orgies made me shiver. I don't know, I haven't seen any of his new work for a while.

GROTH: As I recall, you have mixed feelings about Joe Coleman.

WOODRING: Well, when I first heard about him I was terribly intrigued at the idea that he might actually be a potential mass murderer who kept the impulse in check by sublimating it through his artwork, which is how he described himself. I came to doubt that, and that took a bit of the bloom off the rose. But it's for him to say. He's an amazing artist, just astounding. I wouldn't hang one of his pictures in my house; they're too upsetting to me.

GROTH: You mentioned earlier that you thought I was a little trepidatious interviewing you, and that's true to some extent —

WOODRING: I was just asking – you seemed to be putting it off.

GROTH: There were a number of reasons, and I guess it comes down to certain things about you that I don't understand. One of the many things that I don't understand is some of your interests that I find hard to comprehend. For example, you're into Mark Pauline and Survival Research Laboratories, and you're interested in body piercing and that sort of thing. Can you tell me what you find fascinating about ... Well, maybe you can talk about Mark Pauline?

WOODRING: Mark Pauline interests me because he's a really smart guy who's doing things that nobody's ever done before. He's using technology as a medium of expression and as a medium of aesthetic exploration instead of using it to build products with. I don't know anybody who's done that to the extent that he has, and I also am amazed by him because he seems to be completely fearless and completely willing to push anything to the furthest extreme. He's willing to put himself in jeopardy at the hands of the law and he's willing to risk killing himself or risk killing others. [Laughs.] He thinks big and works big and there's a tremendous amount of destruction to his work. I don't like explosions and loud noises and things like that — I've been to a couple of his performances and I was just a nervous wreck. I don't even like firecrackers. When I'm up at your house, Gary, and you're setting off bombs, I always go down to the basement and sit on the floor against the wall with my fingers in my ears.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Is that right?

WOODRING: Yeah, So I don't really enjoy experiencing that kind of stuff as much as I enjoy thinking and reading about it afterwards.

GROTH: What value do you think that has? Exploding ... I mean, I can see it as an amusing distraction ...

WOODRING: I think one value it has is that it takes elements that people are familiar with and puts them in an entirely different context. And that has the potential to really shake up the world. If people start thinking differently about very powerful objects that they're surrounded with, that can bring on a revolution.

GROTH: You think that's plausible, that anything like that would bring on a revolution?

WOODRING: Well, "revolution" is too strong a term, I guess. But it's significant that he's doing these things at a point in history when the mechanical is becoming obsolete. I think Pauline's work is either a final flowering or an emerging new beast. I think what he is doing is not just entertaining, it is showing us a side of technology we haven't seen before. Exactly what value does it have? I don't know. What value does Rembrandt have? Can his paintings change your life? Do they say something valuable, something usually unexpressed about humanity? Do they point to the divine? Maybe Pauline's work has no catalytic value, but I think it does. He's a great conceptual artist who doesn't let his ideas remain concepts. He actually goes out and builds the huge dangerous juggernaut that goes galloping around with a guinea pig at the controls. It’s a great concept but an absolutely astounding reality.

GROTH: I remember we were at a show at COCA [the Center On Contemporary Art in Seattle] and Mr. Lifto was there —

WOODRING: The Jim Rose Sideshow.

GROTH: Yeah. And you were pretty mesmerized by that stuff.

WOODRING: I think everybody there was pretty mesmerized by that. There were pools of saliva on the floor, I noticed, as people were filing out. Weren't you taken by that?

GROTH: Yeah ... I think it was almost more of a transcendent experience for you than ... I mean, I was certainly in awe of the sheer perversity of it all.

WOODRING: Well, I was too. I wanted to see if Mr. Lifto was going to pull his dick off with a cinder block.

GROTH: [Laughs.] Right, we're all interested in that.

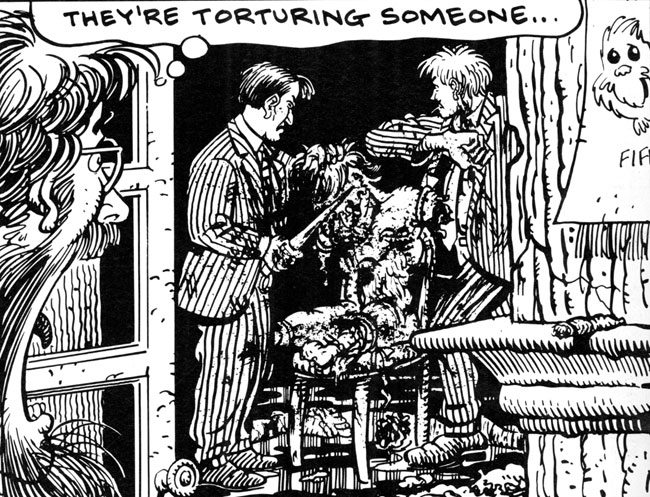

WOODRING: And I wanted to see if his nipples would rip out. But also, that kind of thing, it's like a lot of things that are hideous to watch but quite different to experience. There was another show at COCA ... Well, let me tell you. Some acquaintances of mine were in town and wanted to do something. They were rather conservative people, out here on vacation — one guy was a banker and he brought his friends up to Seattle, and I said, “Well, there's this thing down at the Center On Contemporary Art, we can go see that.” And it turned out to be this heavy duty S&M lesbian extravaganza where, among other things, there were these gigantic bull dykes sitting in cages wearing leather pants with their breasts exposed and filled with needles so that they looked like hedgehogs. And these heavy-handed death and mutilation themes, little tableaux with frightening women in them. My right arm still doesn't quite work right from where this one woman grabbed me by the biceps to steer me around from going behind one of the cages which I was trying to sneak behind. She tore my muscles permanently with her fingers.

GROTH: Jesus!

WOODRING: This was a woman who could have torn my head off with a punch in the face. [Groth laughs.] It would have been like punching at a cantaloupe or something. Strapping monster of a woman. But there were things there that were ... I thought they were a lot less frivolous than the Jim Rose Sideshow — women with really serious, large piercings, big holes in their bodies. If you look at National Geographic and you see those pictures of people extending their lips or their ears or scarring themselves, and you get sort of a strange nostalgic feeling, kind of a compulsion to look at those pictures, and a sense that they're not doing it because they're crazy, but because there is some reward, then there's something there for you. I suppose that's something that most people have the potential to do to themselves and derive the benefits from. And right now, of course people are doing it in this country in unprecedented numbers — there is a lot of interest in piercings and all the things that go with it.

GROTH: What personal benefits do you think can be derived from that?

WOODRING: For one thing, it messes with your head in a really interesting way. When you see a big, huge, glittering, stainless steel needle going through an inch of your flesh, it does something funny to your mind: it goes against everything you ever thought about protecting your body and avoiding pain and everything else. It releases endorphins which can make you feel good, it does funny things to the sex current in your spine. It’s a very tantric thing in that you experience a really strong, but subtle, non-orgasmic sexual current flowing through you that can also have a strong psychological effect on you. People who really subject themselves to heavy duty torment of that sort, God only knows what they're experiencing, but it must be, like you say, transcendental.

GROTH: Do you think there's a sense of desperation to doing that? People just having to find new experiences because the experiences we're used to no longer register with any intensity?

WOODRING: No, I don't really think so. That's like saying that people have sex because they're so jaded that attending church socials just doesn't do it for them anymore. I think it' s wholesome to take psychological risks, and if it' s done safely with medical precautions, jabbing a steel rod through the head of your cock messes with your mind more than your meat. And that, after all, is the point. But people confuse this sort of thing with self-destruction. Installing an ampallang has a large element of pain, of course, but it's part of a bigger experience, and the pain is not necessarily pain per se. Catching your penis in your zipper, now that's pain! Nobody in their right mind would do that for kicks.

GROTH: Earlier, you said you didn't know what value Mark Pauline's machines might have, and that you didn't know what value a Michelangelo or a Rembrandt might have either, but clearly you value good drawing over bad drawing and you look for certain transcendent qualities in art, so you must have a core belief of what good art is and what its potential is.

WOODRING: Well, for myself, good art points towards the invisible world. Either it's just really beautiful because it puts you in mind of some unbearably sweet aspect of this world, or — and this is the case, I think, with Rembrandt — it puts you in mind of something which is, to use that word again, transcendental, something divine. Rembrandt's old women have a divine quality which is very, very rare and precious and not faked; it comes out of a quality that he had, an understanding of life and humanity and he manages to transmit it. It's a message about life from a superior human being. Those things are rare — a damn sight different from Leroy Neiman.

GROTH: [Chuckles] right.

WOODRING: So there's that. And in a way, I think that that's sort of the cheapest thing but it's also the most potent. And this also ties into a question that I've had for a long time about whether comics are capable of being as important and significant an art form as, say, literature. I guess I've come to the conclusion that they can't be.

GROTH: That's sobering.

WOODRING: I guess I think that it's true because the example that always comes to my mind is Jean Valjean's redemption in Les Miserables — if you're locked into the flow of that story, when that moment comes it can just completely knock you down, even if you don't have any thoughts about Christianity in your mind or any early experiences with Christianity to be revivified by this experience, It makes you know what Christianity is all about, BOOM! in that one second. And he conveys it like a saint conveying an experience and imparting knowledge.

And I think you couldn't do that with a comic strip because those words flowing through your mind trigger an internal revelation, and I think a picture connected to those would be self-limiting. You couldn't draw that as well as you can experience it in your mind, as deeply, It goes beyond images and it goes beyond even the words and I think that will never be drawn as well as it is conveyed in those words. I think what pictures and words both do is they trigger responses, they set off bombs deep inside your inner system, and these things pop up to the surface where you see them and it can be a life-transforming experience.

GROTH: Do you think painting or film is intrinsically inferior to literature for much the same reasons?

WOODRING: Well, “inferior” may be the wrong word. I think literature is a better medium than drawing for conveying profundities because it is more abstract. The word “table” is a much, much more abstract symbol for a table than a drawing of a table, and is less likely to conjure a codified notion that may stand between the reader and the message.

GROTH: You said something that I can't imagine too many cartoonists saying, and that was, that there haven't been any Victor Hugo-caliber cartoonists or Shakespeare-caliber cartoonists, but you did go on to say there were William Faulkner-level cartoonists, which is a reasonably subtle distinction. So there's this ceiling that you perceive. But you see the same ceiling for film?

WOODRING: Well, film is a special case because it can be so unspeakably manipulative. But yes, I do feel that. No screen version of Les Miserables will be able to do what the book does. I'm talking about reality; the less artifice the better when it comes to transmitting the truth.

GROTH: This is a very difficult area to get into and impossible to resolve, but I think it's really fascinating.

WOODRING: But I think you can nail it down bit by bit until you find that you have quite a bit of the terrain staked out. Actually, I guess that language isn't the best way to impart information — psychic connection is. People can transmit with their minds, saints can do that, I think. I've experienced people putting thoughts that I couldn't have had ordinarily in my head for two seconds. And whether it was just me doing it or whether it was them doing it, I don't know. I was in the presence of a Eastern Orthodox Catholic bishop, and I have a powerful antagonism for Catholicism and Christianity, so I'm not predisposed to like his kind, but he was doing saintly work, he was going into Cambodia and working against the Khmer Rouge, and he told this very simple anecdote about Saint Francis, a story that I had heard before, and in the telling of it, he conveyed to me a sense of what divine love is — I mean a wholly different emotion from human love — and I just experienced this profound feeling for a few moments and the impact stayed with me. I really feel that there is something there to work towards.

GROTH: More profoundly than if you'd read it?

WOODRING: Yeah. Because I personally think he did impart something. He made a connection on a different level — it was something that he experienced and something that was driving his life, and it was communicated.

GROTH: Do you think that same feeling could he imparted in theater?

WOODRING: I suppose it could if that sort of a person were onstage trying to do it. Yeah, I think there's no question that it could. And I guess that it's possible that someday some cartoonist will come along and produce things that nobody has ever seen and everybody will go, “This is the greatest art form that ever existed. This goes beyond literature, this is better than Homer, this is better than Shakespeare.” But that's something I can't imagine at this point.

GROTH: It's something we shouldn't hold our breaths waiting for.

WOODRING: No, But then again, people didn't do what Gilbert Hernandez has done until he did it. People just didn't see it.

GROTH: Well now, do you agree with me that comics have somehow been held back farther than the other art forms that have progressed in this century? I mean, it just seems like film has progressed to a far greater extent than comics have.

WOODRING: I can't think of a filmmaker whom I think is a better artist than George Herriman. I think films are harder to assess than comics because it is so easy to wring emotions from a viewer with a film. You know, you put a sad kid or a hot woman up there and run the right music over it and wham! It punches buttons by the acre. Everyone in the audience may be deeply stirred; that doesn't mean the scene was good. Film is dangerously affecting; that much verisimilitude is a potent thing. A great comic is a greater achievement, in my opinion, because it has less equipment to stir the audience with. But I think the reason there are so many good filmmakers and so many good films is because it is a more alluring profession and many more people are drawn to it. I don't think comics have been held back; I think that cartoonists are a breed apart, born to do their work. It's much easier for me to imagine someone drifting into the filmmaking profession than drifting into comics.

GROTH: So you feel comics are superior to film?

WOODRING: Yeah. There may be films that will really, really move me, but I can't get away at some point from the fact that I'm watching actors on a screen, and that what I'm seeing is not really real. Even if the director or the writer is really responsible for the message of the movie and manages to convey his message through this medium, I don't buy it. I still have that obstacle of seeing it as a construct.

GROTH: It's funny you should say that, because Gil Kane would say exactly the opposite when we talk about this. He'd say one of the advantages of film is there are real people on the screen, as opposed to comics where you're drawing these people who are supposed to represent real people but obviously aren't.

WOODRING: Well, obviously what one looks for has a lot to do with it. If you really love comics and then you come across one that's really great, you feel this huge rush of warmth at the fact that this practitioner has succeeded and melds with the message and the other effects you're deriving from it. So there's that. Two of my all-time favorite films are Koyannisqatsi and Fellini's Satyricon. Koyannisqatsi is a transcendental film as far as I'm concerned, the most perfect blend of images and music I've ever seen, and a message that is bone-chilling, completely horrifying, completely terrible, and undeniably true, to a certain extent at least. And then for my money, Fellini Satyricon is the best portrait of humanity that I've ever seen, the most accurate and deep portrait of people that I've ever seen.

GROTH: You told me that one of your favorite films, or a film you thought was one of the most flawless you’ve ever seen, is It's a Wonderful Life, which surprised me. What was it about that film that took you?

WOODRING: Not the message at all, the message is silly, but the technique is inspired from one end to the other. Perfect, perfect cinematic storytelling in my opinion. From the first frame where you see a sign that says, "You are now in Bedford Falls." It doesn't say, "Now entering Bedford Falls," or "Bedford Falls, population 2,000" — "You are now in Bedford Falls." OK. That's so perfect! Another thing that I think is a stroke of genius in that film is at the pivotal moment where the angel is first shown, when George Bailey is standing on the bridge and he’s about to jump, you have this head shot of George, and then you cut to a head shot of the angel standing there, and they’re both just occupying the screen at approximately the same place, and that is an absolute cinematic error. When you do that, it's a pop! All of a sudden it looks like one character has turned into the other character. But Capra does that, he cuts from George to the angel and then he cuts back to George and it's your first glimpse of the angel and it's breaking the rules like any good artist will do in order to derive a skewed, abstract effect. And it's just such a brilliant fucking touch. I'm astounded at his audacity and his understanding that that would work as well as it does. It fucks with your head to introduce this error — at the same time your senses are kind of outraged and you're wondering how to cope with this, this essential character has been introduced.

(Continued)