Nicole Claveloux's comics come across as odd, mind-bending "What If's." The kind of imaginary comics one would expect only to exist in Hicksville's lighthouse in Dylan Horrocks's eponymous graphic novel. Symbolist comics evoking internal states, giving fantastic flight to common emotions in colors and landscapes that border on the surreal. They are glimpses of a road not taken on which comics evolved differently, sending their green shoots off into modalities that I would be loath outright to call feminine, but from which comics would certainly have benefited had more women been attracted to and accommodated within the form at an earlier stage in its history.

As it happens, French comics have historically been just as unaccommodating of female creators as America's. Claveloux (b. 1940) only spent about a decade, in the '70s and early '80s, working in the form before seeking other avenues of expression, as a painter and illustrator and in writing and drawing children’s books. Her main comics effort was a quirky comic for young readers, Grabote, which ran in the popular children’s magazine Okapi between 1973–'82. Sadly this charming, lightly philosophical strip in the tradition of Herriman's Krazy Kat by way of F'Murrr's parable-like humor comics about sheep, is largely forgotten today. The Green Hand and Other Stories, newly released by New York Review Comics, might help stimulate new interest, however (and for those eager to make Grabote's acquaintance, the entire run is available in the original language here).

For a few brief years, Claveloux also contributed short comics to the legendary magazine Métal Hurlant – several of which were published in English in its counterpart Heavy Metal – as well as its offshoot Ah! Nana (1976–'78), which featured women creators exclusively. For the longer of these stories, she collaborated with the writer Edith Zha. The Green Hand collects most of this meager output between nifty hard covers, sensitively translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith and hand-lettered in imitation of the original by Dustin Harbin. It will hopefully be followed by a new edition of their feature-length comics album Morte-saison (1979).

The title story, signed Claveloux and Zha, is the main draw here. Published in five installments in Métal Hurlant in 1977, and in Heavy Metal the following year, it is a technicolor dreamscape drawn from life clocking in at just over forty pages. An almost elegiac portrait of the unbearableness of being. There is no great crisis detailed in its vivid narrative of attempted escape from things as they are, just crushing inevitability as the couple at its center finally submerge themselves in an inky ocean under a neon sunset.

They are a woman, the protagonist, and the bird she lives with in a small, crusty apartment. Drawn as something like a scruffy, stocky, and wheezing marabou stork, he is depressed and quietly destructive, his affliction hatching multiples from eggs around him as he stares bleary-eyed through the window at the outside. She brings home a happy, loving potted plant and paints her hand green to tend it—in French a green thumb is the whole hand—but the bird quickly takes the wind out of its sails, withering it willfully with cigarette butts and a feather off his head.

This prompts her to leave and we follow her as she floats through walls naked, encountering a neighbor, cowering under writhing creeper vines, and then as she relocates from her job at a waxworks to a hotel surrounded by angry woods and haunted by people seeking to connect with something: their food, their sexuality, the divine, her. Effigies to their desires loom outside their rooms. Hers is a moth, wings unfolded, proboscis curled up—perhaps because she shares with this insect her means of celestial navigation, triangulating her course from the negative gravitational pull of her mate. He, in the meantime, talks to a stranger who might be the devil, and futilely seeks a makeover at a fun fair.

Claveloux's pen hatching is fulsome, gathering modeled presence on the paper; her colors are bright, clashing gouache, layered in separate blotches, often defining form through a secondary, contourless outlines. Backgrounds are frequently sprayed on in gradients with airbrush. These hand-fashioned transitions lend to her horizons a kind of psychic intensity that reminds the reader of that these are internal projections.

There is an undeniable glow to it that belies the stories’ bleak outlook, a sense that our mental decay is somehow also beautiful. So although “The Green Hand” rivals such comics as Joshua Cotter's oppressive cartography in Driven by Lemons or Tsuge Yoshiharu's subversively realistic Muno no hito in its unrelenting portrayal of depression, it strikes a more cosmic note.

The rest of the volume is made up of shorter stories in similar or parallel veins, created by Claveloux on her own. Most are from Ah Nana!, short black-and-white parables of desire, anxiety, and struggle, and variously successful. She trades in a kid of magical realism rooted in very ordinary life, a richer, internal counterpart to her contemporary’s Caza’s virile alchemical mixture of social realism and fantastic metaphor in the great Scènes de la vie de banlieue ('Scenes from Life in the Suburbs', 1977–79).

Plant metaphors flourish in Claveloux's comics, for example in "The Little Vegetable Who Dreamed He Was a Panther"—about a stout, rooted being dreaming about unfettered movement—or in the lush, oneiric "A Little Girl Always in a Dream", which channels childhood memories of your first period. Themes of family also recur, often emphasizing its discontents—the funniest is "Underground Chatter" with its subway anecdote of contrasting savant and monkey babies unsettling a commuting mother-to-be, while "No Family" is a picture-book-style story about relatives murdering each other, rendered in a harsh, very '80s commercial chic. A little too on the nose.

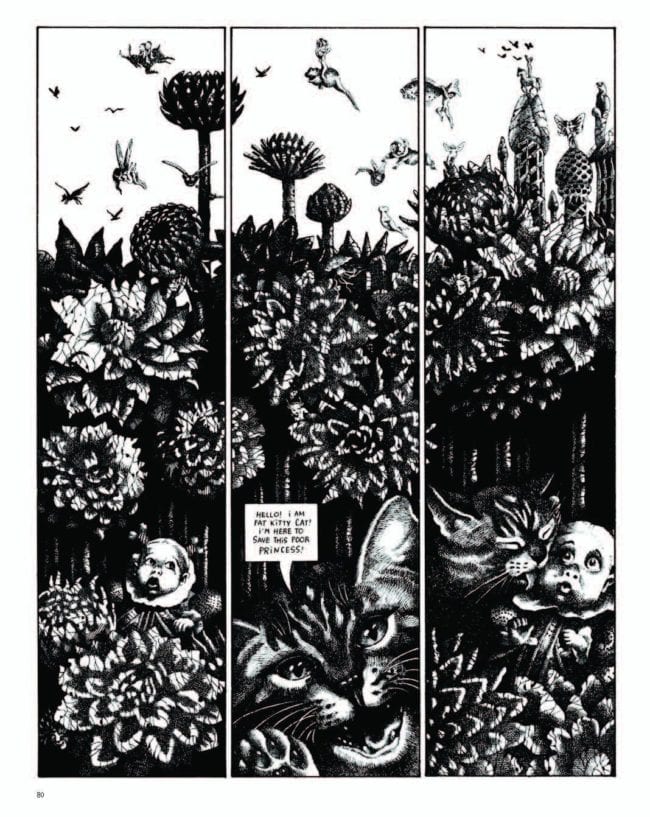

We learn from the interview with the two authors in the back of the book, that Métal Hurlant editor Jean-Pierre Dionnet called these comics "Marguerite Duras in comic form," which does not seem far off. I am unfamiliar with that distinguished author and filmmaker's prose, but Claveloux's comics certainly possess some of the otherworldly, pensive, and melancholy lyricism of her films. Perhaps appropriately for comics, however, they are funnier and more irrepressible. Fairy tales clearly form the substrate of Claveloux's approach, and some of her best stories retain their vernacular punch. Most successful is this regard is “The Tale of Blondie, Dearest Doe, and Fat Kitty Cat”—a tightly rendered gothic tale of a baby fleeing her evil stepmother queen to shack up with a cat in the forest. Its affluent, fervid preadolescent symbolism recalls Alice in Wonderland, which Claveloux—surely not coincidentally—had illustrated with inspired Heinz Edelmann-like inflections of John Tenniel in 1974.

I am not sufficiently familiar with Claveloux's subsequent work properly to assess where The Green Hand belongs in her broader oeuvre, but judging by examples online of her more recent, rather over-baked paintings, it would seem the period in which she committed to comics was not only a particularly propitious one for French comics, but also for her as an artist. The work, certainly, has that air of being created at an inspired moment, with “The Green Hand” in particular presenting as a little-recognized masterpiece.