PLEASE NOTE: THE FOLLOWING DISCUSSION 'SPOILS' PLOT DEVELOPMENTS THROUGHOUT PARALLEL LIVES. VIEWER DISCRETION IS ADVISED.

* * *

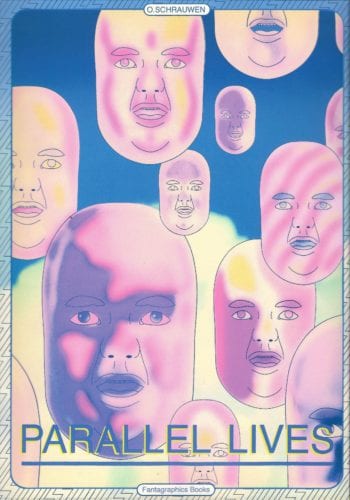

MATT SENECA: Parallel Lives is the new book by Olivier Schrauwen, following up his 2014 opus Arsène Schrauwen. I believe both of us are on record as being huge admirers of that book, and Schrauwen’s work in general. I think the guy’s never put a foot wrong, and I personally count him as the most interesting European cartoonist currently being translated for the English-speaking market. So this book is a big deal! It collects six stories of varying length, all but the last of which appeared by themselves in other venues before being presented as part of a cohesive work here.

MATT SENECA: Parallel Lives is the new book by Olivier Schrauwen, following up his 2014 opus Arsène Schrauwen. I believe both of us are on record as being huge admirers of that book, and Schrauwen’s work in general. I think the guy’s never put a foot wrong, and I personally count him as the most interesting European cartoonist currently being translated for the English-speaking market. So this book is a big deal! It collects six stories of varying length, all but the last of which appeared by themselves in other venues before being presented as part of a cohesive work here.

What jumps out at me about the book as a whole is its focus on the future. All of these short comics fit into the science fiction genre, if a typically bizarre, Schrauwenesque reading of it. Some of them have an explicit future setting, while others contain glimpses of times to come or advanced technology. This is interesting to me because the great majority of Schrauwen’s previous works have been investigations of the past. One could make the argument that the two main concerns of Schrauwen’s pre-Parallel Lives work are European colonialism, and early-20th century styles of cartooning. This book leaves both behind, and though it’s clearly animated by the same sensibility that powered Arsène Schrauwen, it’s unmoored from that book’s essential narrative concerns.

Then again, this book and Schrauwen’s others also have a lot in common…

JOE MCCULLOCH: That’s very true. In fact, it goes back a little further. For context’s sake, here’s a list of Schrauwen’s book-format comics:

*

My Boy (Bries, 2006)

Le miroir de Mowgli/Mowgli's Mirror (Ouvroir Humoir, 2011; Retrofit/Big Planet, 2015)

The man who grew his beard. (Fantagraphics, 2011)

Arsène Schrauwen (Fantagraphics, 2014)

Parallel Lives (Fantagraphics, 2018)

*

What all of these books have in common -- save for Mowgli’s Mirror, which is not quite 48 pages -- is that they’re all compilations of short pieces. My Boy is a series of vignettes; The man who grew his beard. is a traditional collection of previously-published stories; and Arsène Schrauwen, while ostensibly a graphic novel, was originally released as self-printed comic books by the artist. Schrauwen even goes so far as to urge the reader at each chapter break to put the collected edition away for one or more weeks, to foreground its nature as a compendium. He’s currently working on a new project, Sunday, which only has one self-published chapter out as of now, so it looks like this practice will continue.

In addition, while all of these books focused intently on the past, they do it in a somewhat algebraic manner. My Boy was, by the artist’s own estimation, a “forgery” of early 20th century comics, a la Winsor McCay; Mowgli’s Mirror is a wordless parable of man’s incursions on nature, nodding towards and ironizing Kipling; The man who grew his beard. presents an indistinct, phantasmagoric past, with added colonial coloring; and Arsène Schrauwen, of course, imagines the life of Schrauwen’s own grandfather in the Belgian Congo as a sort of very aloof, very formalistic slapstick comedy.

I bring all this up because, although I think Schrauwen’s work has a reputation for being surreal or weird, I’ve found him to be the type of artist who really ‘shows his work’ on the page. Arsène Schrauwen is powered by very literal visual similes, some of which are explicitly defined on the book’s cover: a person with a blank circle for a face representing “The Unknown”, or a goblet of trappist representing “Freedom”. The man who grew his beard. revels in juxtaposing drawing styles against one another, which provokes contemplation of what is on the page, rather than immediate absorption. My Boy places the early period of American newspaper cartooning in as firm a pair of quotes as can be imagined. And, because Schrauwen tends to work in short bursts, you get the sensation that you’re following his thoughts from idea to idea along a relatively straight line, from the early pastiche of My Boy to the thorough imagineering of familial/national/colonial history of Arsène Schrauwen.

And though some of that is surely an illusion -- a realization on the reader's part as fictive as the ‘facts’ of Arsène Schrauwen’s life -- it encourages a lot of thought. Or even identification; I bought a copy of My Boy off the Bries table at the last MoCCA festival held at the Puck Building, in 2008, and I liked it so much that I scampered back home immediately to Pennsylvania to write about it on my Blogspot dot com webpage. Critics love to do that with artists who show their work, because the systems provide a ready-made chassis on which to build essays; the artist has done some of the critic's labor for them, and the critic is grateful. Now Chris Ware praises him, Art Spiegelman praises him; he’s in the New Yorker, discussed on NPR - Schrauwen is a big deal, and I have to check myself so as not to be overly precious about his work and thereby prove myself the superior analyst, because I read his first book when it was new. The fine German critic Oliver Ristau reminds me that Schrauwen did some work for the venerable Belgian children’s magazine Spirou early on, before the limitations of that venue proved ill-fitting; he’s a guy who likes jokes, a lot.

MATT: Shall we indulge him then? A good joke, Schrauwen knows as well as anyone, is all about putting the pieces in sequence. The subject matter of Parallel Lives diverges from earlier Schrauwen comics, but at the same time it reads very much like an answer to Arsène Schrauwen (though the first piece collected here came out during the serialization of Arsène). Where that book presented the highly fictionalized story of Schrauwen’s colonialist grandfather, this book begins with a story starring the artist himself, before its subsequent chapters trace the travails of his descendants far into a future that only this guy could dream up. You suggested dissecting this book into its component parts to see what makes it tick. Let’s climb the family tree...

*

Greys (previously published as a standalone comic by Desert Island, 2012)

MATT: I’m a big fan of fictional comics that present their creator as a character, especially in the art/lit comics world that Schrauwen’s work, and The Comics Journal for that matter, resides in. It’s a great way of pulling the rug out from under the reader - of playing a joke on us! Readers of what Dan Nadel (RIP) called “shmart momics” have been so conditioned by years of hard-realist, painfully honest autobio pieces from Crumb on down that the bare fact of seeing the cartoonist themself drawn on the page wraps everything that happens in a story, no matter how absurd, in a gauze of presumed reality that has to be actively torn away. To me, making yourself a character in your comic is almost like making the reader a character too - going from giving a presentation to having a conversation, if you will.

Schrauwen does a great job of leveraging that baggage in “Greys”, loading the reader down with more and more absurdity until whatever credence you’ve lent him inevitably collapses. This story, while it establishes the science fictional milieu of Parallel Lives, feels more like a send up of autobio comics than anything else. It’s also a great forum for Schrauwen’s deadpan humor, which is the signature aspect of his writing to me. He never breaks kayfabe, beginning his story at the drawing table (autobio comics cliche #1) before discussing masturbation (cliche #2) and unsuccessfully attempting sleep (shades of Kevin Huizenga’s hyperquotidian Ganges). A close encounter with a group of aliens - the titular Greys - immediately follows, but even this isn’t totally foreign territory for autobio comics (see Barry Windsor-Smith’s testimonial in Streetwise... and who could forget that Grant Morrison alien abduction video?).

JOE: Fantagraphics put out two volumes of Windsor-Smith’s Opus around the turn of the century, which had a very serious treatment of paranormal autobiography, yeah.

MATT: So personally, I felt like it was at least possible that Schrauwen might be relating something he believed had really happened to him -- and given the fake-autobio nature of this comic, was inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt -- up until the panel where the aliens “found the time to release me from my underwear,” which is illustrated with a medical-text style closeup of Schrauwen’s hairy, uncut dick and balls. This is a funny comic whose first joke doesn’t come until more than a third of the way in, but boy does that joke, which packs the accumulated weight of the thousand more seriously intended penile self-portraits from Important Cartoonists we’ve been assured are No Laughing Matter, kick hard! The opening of the book states that Schrauwen felt comics was the only medium that could put across the nature of his experience successfully. It’s a punchline by the time it’s repeated at the comic’s end, given that this is the medium at its most basic: narration rendered in text over very literally illustrated panels.

But as funny as “Greys” is, I find its overall emotional tenor to be surprisingly in line with the kind of comics it deconstructs - a vague, permeating melancholy. After Schrauwen’s orgasmic adventure, he’s shown a vision of humanity’s every act of mass self-destruction, one after the next, that extends from primordial times into the future and culminates with the destruction of the universe after a miniature black hole is stolen from the Large Hadron Collider. This isn’t earth-shakingly innovative content by any means, but the deadpan affect of Schrauwen’s narration, so adept at underlining his funny pictures or ludicrous plot twists, can be quite bracingly sad too, like listening to an autotuned voice sing a song of heartbreak. The sections of Arsène Schrauwen that focused on its main character’s unrequited love for his cousin’s wife had a legitimate emotional charge, and this comic’s narrative crest does as well.

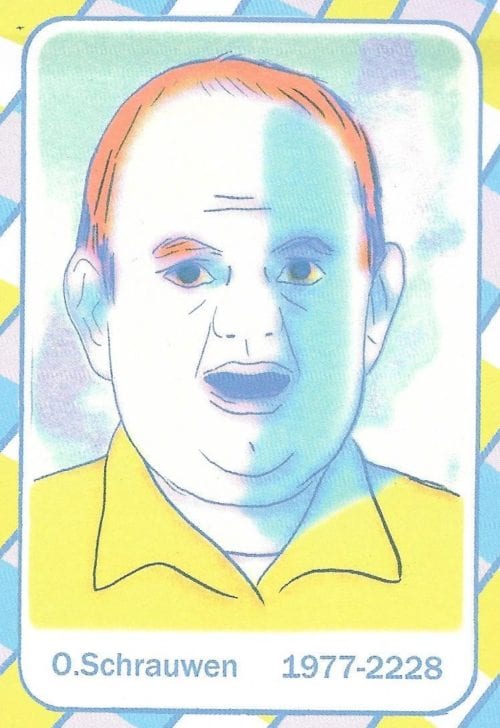

JOE: It’s interesting how much this comic has changed from the first time it was presented; of all the pieces in this book, “Greys” is the one that bears the most weight of a contextual shift. The 2012 Desert Island edition is a stapled comic book with no cover stock, its story ambling out onto the back cover - the art is presented at two panels per page, quite fuzzily; it looks like a bootleg, which belies the sophistication of a comic published under the auspices of an arts-focused comic book store, the owner of which was at that time co-organizer of a prominent alt comics show, the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival (now Comic Arts Brooklyn), where "Greys" was made available for sale. The aesthetics of the printing, then, can be read as a way of accommodating Schrauwen storytelling approach, which, as you’ve said, is very akin to that of Arsène Schrauwen. The two works even begin with the same type of image: a big, jolly close-up of “O. Schrauwen,” graphic novelist, who does not especially resemble the real Olivier Schrauwen.

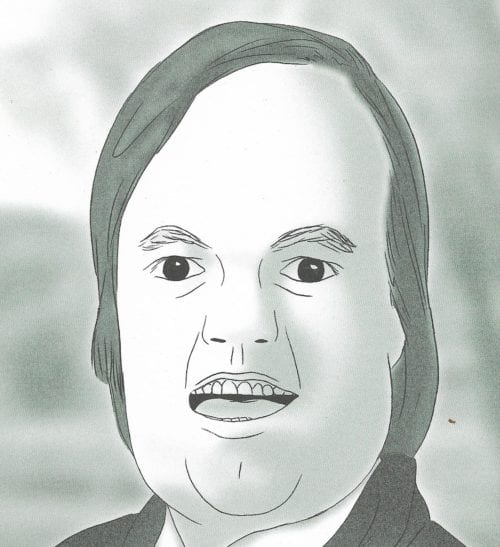

MATT: That image of “Schrauwen’s” face, which repeats throughout this book as the first panel of a few stories, with increasingly absurd hairpieces or makeup added onto his identical future “relatives” a la that Key and Peele Shrine Game sketch, sums up his approach to the autobio comics genre better than I ever could. It completely short-circuits the reader’s ingrained reaction to seeing an author draw themselves - where most cartoonists are interested in generating some kind of empathy or other with their self-portraits, Schrauwen’s goofy ass slack-jawed grinner functions as a punchline in and of itself, one that only gets funnier as it repeats throughout this book. It reminds me of that Dan Clowes comic where a professional caricaturist’s ultimate act of self-annihilation is drawing himself as ugly as he possibly can.

JOE: "Greys" was a very funny comic to read at the time of its original release, in a form that evoked a sense of haste, like the whole thing was stolen from somebody’s bedroom and printed in secret. I don’t know if it was conceptualized in the same way as Arsène Schrauwen, with the artist writing out a stream-of-consciousness text and then pairing some of that text to drawings which deliberately repeat some of that text’s information, but it feels very similar. “Greys” is much more straightforward, though - it lacks much of the word/image punning of Arsène Schrauwen, instead focusing, to my eyes, on the pleasure of odd drawing. A weeping graphic novelist clad only in a hospital gown rising up at gigantic size to prevent the 9/11 attacks by swatting an aircraft away from the Twin Towers and then storming around the city like Godzilla in a fit of emotional agony is served well by the direct approach.

JOE: In Parallel Lives, “Greys” plays a much different role. It’s been almost totally rearranged as six-panel pages, with the visual quality much clearer and sharper; there’s a handful of new panels to expand the story, the punctuation of the text has been corrected throughout (to less humorous effect), and some of the wording is different - this is the Graphic Novel version of a comic book. Or, if you want, the BD album collection of a magazine comic. And, as part of a graphic novel, it now functions as a sort of prelude, explicitly beginning this new book with evocations of Schrauwen’s prior book, Arsène Schrauwen, as if to demarcate a point of departure for the new thinking that animates the rest of Parallel Lives. The form of “Greys” is similar to the artist’s older work, we can see, but the science-fiction content is new, and in subsequent stories the form too will evolve, as humanity does in the future. It’s all quite integrated. So, the grey tones of this story come to represent the past, like a long, pre-credits flashback in a movie, and I think its individuality is dulled by this new context. I found myself anxious to get on to the later stories this time.

And, as if to anticipate my reaction, “Greys” also now sets up plot points for later… but we’ll get to that when we come to it.

*

Hello (previously published in the anthology Mould Map 3 by Landfill Editions, 2014)

MATT: This story kicked off a streak of Schrauwen having the best comic in a number of very high-quality anthologies. Mould Map 3 today looks as emblematic of the 2010s in art comics as Kramers Ergot 4 was of the 2000s to me. As in today’s wider comics marketplace, Schrauwen’s contributions felt a little outside of the space everyone else was working to carve out. Where piece after piece in Mould Map 3 predicted a sweaty, gritty, dystopian future that would put humanity through the sluice, “Hello”’s rendering of our eventual fate is more Peter Max than Mad Max.

Arsène Schrauwen was where I first noticed Schrauwen’s facility for writing and drawing parties, one matched only by his fellow Belgian Brecht Evens. This might not sound like a particularly special skill to have, but think about it. Most people never go on adventures or solve mysteries or face shattering personal crises, but they do party, and in so doing they feel more alive. So much of drama is about harrowing characters in order to reveal the grain of selfhood that lies beneath the facade they present to the world, and parties do that work on people in a singularly pleasant manner. Schrauwen’s work shows an innate understanding of this, and “Hello” showcases the first of a few parties in this book, with rising action that climaxes in a futuristic bacchanal.

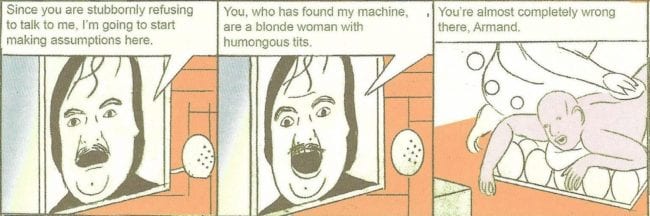

The Schrauwen family member spotlighted here is Armand Schrauwen, who is actually an inhabitant of our past - 1986, to be precise. But Armand is an experimental scientist or artist, who a dinosaur that plays a bit part in the story casually compares to John Baldessari, and through videorecording or perhaps some much more highly advanced process, is able to beam his extremely YouTubesque video diary into an antique TV purchased on a lark by an citizen of the future. Thus he communicates the details of his banal, pathetic life to the inhabitants of a fantastical world that looks like a cross between Pixar’s Up and the cyberpunk rave scene in Matrix Reloaded.

JOE: It’s interesting that you refer to Armand as an artist! He identifies himself as “an amateur technician,” but he really is an artist by the terms of the story, isn’t he?

When I read Mould Map 3 -- a crowdfunded anthology from the UK, heavy on young contributors, the down-to-the-wire financing of which became sort of a community cause -- I was also struck by Schrauwen’s contribution, but for how skeptical it seemed in the midst of that blazing moment. I mean, a lot of pieces in the book expressed ambivalence about the social and technological state of things, or the role of the Artist, but Schrauwen seemed to despair of the very idea of addressing the future through art, framing the process as a screwball comedy between protagonists that never meet.

MATT: But that’s not presented as being a big deal or anything. Authorial remove is an interesting (and I think under-discussed) aspect of Schrauwen’s writing. He never evinces much concern or empathy for his characters - everything that happens to everyone could be cause for emotional reaction, of course, but more often than not it’s all a big joke. This is especially notable given that he uses “himself” and his “relatives” as characters.

Anyhow, you’re correct: Armand’s communications with the future are strictly one-way. The 20th-century TV the futurians half-interestedly watch his spiral into despair on obviously has no option for sending messages into the past. And anyway, everyone in the year whatever is way more interested in the big house party they’re planning, at which they fuck, snort, and drink everything they can, eating cans of Heinz pork and beans in homage to their new favorite screen star’s diet. The party climaxes with the disillusioned Armand receiving an ecstatic vision, or maybe a legitimate transmission from the future, and achieving a brief moment of actual communication with the inhabitants of the far-flung age whose perspective we watch him from. Of course, he’s housed an entire bottle of vodka by then, so who knows what he’s seeing, and the thrust of his communication with a far-off age is looking for a woman who’ll flash her tits at the screen. The story concludes with a typically callous, Schrauwenesque reasoning for the artist’s transition from historical drama into sci-fi: why would people be interested in stuff that’s already happened?

JOE: Right. Armand, as is very clear from the dialogue, is totally concerned with communicating his work to the future, because he feels he is neither understood nor appreciated by the present. He is A Certain Type of Artist. But the peril of making Great Work with an eye toward posterity is that you can’t control the attitudes of the future audience.

Rereading this story, I was struck by the texture of Schrauwen’s future society. Armand’s gizmo is discovered by a nameless, seemingly non-binary future person who appears to be the big influencer of their leisure circle. They’ve gotten everyone into the bygone drink of margaritas, and, moreover, they seem to interface with past culture in a slightly deeper way than the others. Some of their friends have adopted racialized body modifications -- the talking dinosaur you mentioned before is one thing, but another one of them is a white person wearing blackface all the time, and another has become a walking kabuki woodblock print anachronistically colored piss-yellow (the skin color is made much more prominent in the Parallel Lives version of the comic, so I presume we’re supposed to notice the racial character) -- but the influencer themself is rather sensitive in trying to incorporate aspects of Armand’s culture into their own life; when they break up with a lover using some of Armand’s language, you can see they desire to learn from the past, rather than just consume it. They are a good reader, a good audience.

Yet it’s a doomed effort; there is always a screen between the artist and his future. Not just the literal screen of the monitor from which Armand broadcasts, but the fact that he can’t see outside his own cultural conditioning. Some of what he says is total Al Bundy stuff, just hyper-heteronormative dross about future blondes with big tits fucking robot studs, which Schrauwen contrasts against the future-tense influencer working a dildo in their ass with their male-presenting partners. The future, in this way, is a gulf that cannot be crossed by someone fixated on present norms: gender norms, sexual expectations, etc.

The thing is - this isn’t really the future, right? There were contributors to Mould Map 3 who were not cisgender, and there was work in there that addressed gender and sexuality -- to say nothing of, you know, the rest of comics history -- and seeing Schrauwen’s work among those was striking in that it centered the perspective of a character who does not understand things outside of the circumstances of his own identity, and therefore exists in the metaphorical ‘past.’ He’s empathized with, for a while, by younger people, but eventually forgotten: maybe for the best. Given the predominance of men who can’t get over themselves throughout Parallel Lives, it’s often like the book itself is positioned as a befuddled observer, uneasily navigating the present-as-future. And then we remember that Schrauwen’s works have otherwise lingered on the past...

MATT: Yeah - Arsène Schrauwen, especially, spun comedic gold out of what we in the present inevitably see as the banality of the past… but that stuff is still banality. Even toward the end of that book, its artist seemed decidedly tired of the period drag he’d draped his story in, pivoting first into fantasy with an attack of half-human leopard men, then into a very specific quasi-futurism with the construction of a technological wonderland deep in the African jungle. The past is pork and beans, the future is whatever you want it to be. Maybe Schrauwen just didn’t want to hold back his prodigious ability to invent from whole cloth anymore! His vision of the future is basically a point-A-to-point-B extrapolation from our own present - or just the intensification of a culture shift that’s already begun, as you suggest. But powered by Schrauwen’s unique creativity, which forgoes the big sweeping visions sci-fi usually affords and focuses in instead on the ins and outs of leisure, it feels novel.

This is in part due to Schrauwen’s switching up the structure of his pages. Where his previous work mainly used a gridded structure seen in any number of comics (usually a 6- or 8-panel page layout), here he scales up to a 6x4 24-panel grid, usually broken up slightly by one or two larger keystone images. The grid will get even denser in subsequent stories. This obviously enables Schrauwen to pack more information into less pages; “Hello” and later chapters of Parallel Lives could have filled out album-format graphic novels if they’d been illustrated more expansively. But it also forces Schrauwen into a highly elliptical visual treatment of the future, with the technophilic landscapes we expect from sci-fi comics relegated to a few geometric shapes and bold colors in the backgrounds of tiny panels. Schrauwen is focusing on people, using the futuristic setting not as a character itself (as we see so often in comics), but only the push that puts the personalities he’s playing with in motion.

The narration in Arsène and “Greys”, as well as all the other comics in this volume, is absent from “Hello”, robbing it of some absurdity and giving it a cracked sitcom feel. I didn’t enjoy returning to the story as much as I thought I would: put in context among other Schrauwen works rather than Mould Map, it feels a little less distinct. Still, as the only story here to straddle our world’s past and its future, it’s an important piece in the puzzle Parallel Lives presents, acting as a pivot point for the book’s subject matter.

*

Cartoonify (previously published in the anthology Volcan by Lagon Revue, 2015)

MATT: This is my favorite of the anthology shorts that Parallel Lives reprints. It’s the funniest thing in the book to me, and contains some smart use of the comics medium that only someone who understands exactly what they’re doing could pull off. The setup for “Cartoonify” is head-smackingly obvious once someone else has thought of it. Oly, who isn’t explicitly identified as a Schrauwen descendant but shares the hereditary vapid visage, downloads an app called Cartoonify that allows him to experience his life as a cartoon rather than reality. A buddy shows up and hijinks ensue. Though many of Schrauwen’s comics through the years have involved altered states of consciousness, whether due to mental illness or exhaustion, alien contact or paranoia, this is as close to a straight-up drug comic as he’s ever come.

I’m burying the lede though, because Schrauwen’s handling of the app’s hallucinatory effects is brilliant. Oly’s buddy Helger takes a double dose and cranks up the cartoonishness setting, resulting in drawings that look to Oly like regular Schrauwen pictures, and to Helger like dashed off doodles of the same subjects. The narration is as droll as it gets, using the by-now familiar trick of literally describing the panels’ contents, and its very dumbness, perfect for the subject matter, creates effective punchlines. The use of comics’ idiomatic shorthand devices - starbursts, sound effects, et cetera - moves from background noise to subject matter, encouraging readers to revel in the uniqueness of the medium, to experience reading comics as a lavish consciousness shift, a designer drug. That feeling is held up by the structure of the story, which begins the moment Oly downloads the app onto his brain’s nanocomputer, and ends with a series of panels that show the iconic Schrauwen-face accruing greater and greater levels of detail as he fades back into reality. “Cartoonify” is a formal coup.

MATT: I see a strong savor of Steve Ditko’s psychedelic-era style in a lot of this comic’s panels, with our boys dressed in outre fashions that could easily have escaped from an issue of Shade the Changing Man and hopping across boxy cityscapes in stiff poses that feel traced from some nonexistent dictionary of heroic cartoon poses. I also found the same kind of hilarity in “Cartoonify” that I have to imagine heads in the days did in Freak Brothers comics, so adept is Schrauwen at nailing the mundane minutiae not of the drug experience, but the drug affect. Oly and his buddy Helger goggle around town in the private cartoon world they’re sharing, causing a ton of property damage, looking with awe at (and drawing the ire of) the poor schmucks who are stuck in the desert of the real. The intensity and novelty generated by looking at things, walking places, taking pictures of stuff, and the big hurdle, interacting with un-high human beings on drugs, are all rendered with deadeye accuracy. This comic feels very late ‘60s, both in its visual style and its utterly decadent foregrounding of individuals’ pleasure-seeking at the expense of the consequences thereof.

It’s funny you mentioned how the world projected by “Hello” leaves the depressingly binary, normative, self-involved Armand Schrauwen stuck in the past, because “Cartoonify”’s future carves out a ton of space for Men Behaving Badly. The stories have similarities too, though. Both Armand and Oly are boors whose pursuit of technological ecstasy inevitably leads to personal failure. Oly’s girlfriend, after being coerced into what for him is a bizarre, exploratory sexual encounter and for her is utterly unsatisfying, even calls him “clownish” before she breaks up with him in an echo of the language used in “Hello”. This is an uproariously funny comic on a grim topic: a dude whose recreational drug use makes him into something completely unfit for society.

JOE: I also think this is the best of the reprinted shorts, but from the opposite end - I found it completely bleak and horrifying, if funny at times. When Oly’s friend comes high-stepping in, I totally cracked up, yeah, but I think there’s often an element of comedy in horror, or at least a sense of absurdity to things going extremely wrong, and by god is that relevant here.

Like: the guy rapes his girlfriend. Her reactions to this are kept mostly internal, but it’s obvious she’s alarmed by what’s happening and doesn’t actually want to have sex, which he forces on her. But, at the same time, Schrauwen is throwing in these diegetic cartoon effects like her clothes sproinging off her body, which represent what Oly is seeing because he’s transformed the world into a cartoon - and, to become a cartoon like this is to abrogate any responsibility for your actions.

MATT: The narration in the panel after Oly climaxes literally says “And, zap, he is back on the streets.” The cartoon Schrauwen creates isn’t a story telling us about Oly’s cartoonified world - the two are one and the same, fused.

JOE: What’s the old Understanding Comics line? “The more cartoony a face is… the more people it could be said to describe.” In cartoonifying the world, Oly reduces other people to a miscellany, and the world becomes a playpen for his personal realizations. Like you said before, Schrauwen doesn’t break character: everything is presented in a light and silly manner, but I found a deep grotesquerie lurking beneath all of this unreliable narration. Cartooning here, the altered state, is like a cocoon,where the altered consciousness allows no input but that of the self. When Oly’s girlfriend breaks it off with him, he cries this big, fat, cloying solitary teardrop, which his even-more-spun-out buddy flicks away... and they’re smiling again!

MATT: There’s a great bit right after that where Helger wanders off to a pinball parlor holding his clothes in a bundle, completely naked! The solipsism is total. I suppose one’s level of willingness to go along with it, or alternately step outside and consider the effect of the characters’ actions, is what determines how funny or scary the story will read.

JOE: Oh, I don’t think Schrauwen is interested in overt moral statements; nothing in his work suggests that to me. But I think the way in which pits formal characteristics of comics against one another undermines the certitude of the story’s reality, and in a story powered by a character’s certitude, that becomes a means of undermining them.

At the end of “Cartoonify”, Schrauwen begins to makes his images more realistic, which is a technique he used at the end of Arsène Schrauwen - where, for four pages, the heretofore monochromatic coloring of the book shifts to an approximation of ‘full’ color, and suddenly Arsène himself is talking like a ‘normal’ person, and characters speak in realistic language, and through this Schrauwen-the-artist allows that the cartooniness of his art in the rest of the book is an imposition of his own perspective on a person who had an interior life, private desires, and a sense of nostalgia, perhaps, about the colonial project Schrauwen-the-younger leaves as self-evident farce. There, he is undermining himself as the author: a fallible god dictating the reality of the page.

In "Cartoonify", he undermines Oly, who slowly comes down into reality, panel by panel becoming more realistic, like a process in animation, where Schrauwen has also worked. The sequence as presented in Parallel Lives is longer than what was printed in Volcan - there’s a whole added page where we stare at this huge image of Oly’s very realistic face, wordlessly. And though it’s poised in the same ‘funny’ way as the closeups of other awkward Schrauwen family faces elsewhere in the book, it’s now very disquieting, because Oly realizes what’s happened - the funny narration is now silent.

I found it a very sinister and fucked story, so obviously I liked it the most.

*

The Scatman (previously published as “Ski-ba-bop-ba-dop-bop” in the anthology Gouffre by Lagon Revue, 2017)

JOE: This, on the other hand, is probably the most optimistic thing in the whole book, and -- coincidentally or not -- is the only one to feature a woman of the Schrauwen lineage: Ooh-lee Schrauwen. That it’s not immediately certain if “Ooh-lee” is how her name is spelled, or if we’re hearing a phonetic pronunciation of something spelled differently, is arguably part of the scheme.

(PLEASE OPEN THIS LINK IN ANOTHER TAB AND PLAY THE AUDIO OVER THE REMAINDER OF THIS SECTION.)

“The Scatman” is similar to “Cartoonify” in several ways. For example. both were published in anthologies from Lagon Revue, a French outfit that put together very fancy, small-run risograph-cum-offset books with the support of various arts- and print-focused continental entities, among them an endowment fund by the fashion house agnès b. (Parallel Lives doubles as a tour of the ways a arts-focused European cartoonist and publishers thereof can try and make things work under the economic conditions of today.) The Lagon-published stories were initially lettered in French and came with an English translation booklet, but the Parallel Lives versions have been re-lettered in English, with essentially the same translations - presumably by the multilingual Schrauwen himself, as nobody else is credited in that capacity.

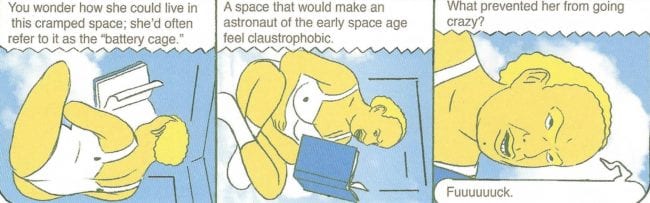

For English monoglots, this makes “The Scatman” far easier to read than it used to be, since, like “Cartoonify”, it exploits a prominent element of the comics form: text. Ooh-lee is experiencing a problem in her life - she’s had her brain hacked by a neuro-troll (because she couldn’t afford a better firewall for her head), and she can’t get the condition treated (because she can’t afford that kind of medical care). No longer restricted to social media, online men now literally mess with women’s heads, and the way Ooh-lee’s troll does it is quite sophisticated - he recites a miserablist narration over her life which she cannot help but hear, and what we see on the page as captions, as if we are reading a gruelingly unhappy slice-of-life comic.

MATT: Both this story and “Cartoonify” also detail the perils of keeping a nanocomputer in your head - a state of being Schrauwen’s future inhabitants will have transcended by this book’s conclusion. We’ve mentioned a couple times now how light Schrauwen’s authorial touch is for someone who includes third-person narration in pretty much every panel he draws. There isn’t a lot of explicit opposition to or even judgment rendered on the actions his characters take. Sometimes the perspective we’re given by the narration is even indistinguishable from the characters’ own, as in “Cartoonify”. Here, though, the pivot is striking: instead of drolly counterpointing the main character’s actions, the narration, a formal element of the comic’s very structure, is weaponized against her. It’s difficult not to read this story as a criticism of male privilege: definitions and narratives that we’ve been conditioned to read as objective are revealed as intensely, caustically biased. It’s a real 180 from “Cartoonify”, or maybe a dark mirror image of it: usually in Schrauwen-world, men aren’t failures, just hapless boobs whose shortcomings we’re encouraged to laugh off before everything works out more or less agreeably in the end. Women, meanwhile, are quite literally forced to bear the emotional weight of male failure and neurosis in addition to that of their own. Sound familiar?

I used to, uh, marvel at comics written by Stan Lee in his mid-’60s heyday because of the casual fluency with which they used all the various avenues the comics medium has developed for incorporating text. The best-written Lee comics would have a speech balloon, a thought bubble, a narrative caption, and a sound effect in almost every panel, each one making a distinct contribution that was also separate from the information the picture they went with communicated. Those old Marvel books showcase a potential for sophisticated narrative forms that comics has largely left fallow since turning to “serious” subject matter - maybe because it’s too much work! Here, Schrauwen uses tools that every cartoonist has at their disposal but most never touch to pull off a comic with a great degree of formal sophistication. It’s every bit as inspired in its use of the comics medium as “Cartoonify” is, but far, far subtler.

JOE: And even more so than “Greys”, “The Scatman” feels like a lampoon of certain stereotypes in comics, with its protagonist openly resisting a malevolent writer/troll’s bad faith Eeyorisms: Ooh-lee is unhappy about her weight, he says; she is sad about her living conditions, her economic position; she knows, deep inside, that her interests are facile and meaningless and that everyone she calls her friends are laughing at this clownish, self-deluding failure. If there is any truth to these statements, it is not this man’s place to announce it in so reductive a way. Luckily, Ooh-lee has a plan to fight back against this abuse... and it involves a certain 1994 Eurodance single by Berlin’s own Scatman John!

Do you know about Scatman John, Matt? He suffered from a stutter for all his life, but was able to incorporate it into his music by learning to scat - harmonizing a communications obstacle by transforming it into art. I don’t know if Schrauwen means to allude to Scatman John’s real life in this story, but Ooh-lee also uses scat singing to combat mischievous speech. Probably nothing is more dangerous in comics than trying to depict music on the page - especially if you’re throwing down lyrics, you run the risk of slamming the brakes on the reader’s engagement as they try to sift among purely visual and ‘auditory’-visual cues. Schrauwen uses this confusion as a means of literally attacking a weaponized aspect of the comic, which is pretty fucking clever. It also leaves Ooh-lee herself at sort of a remove, however, because we’re not privy to her thoughts - in this way, the toxic male antagonist is given the same narrative primacy as the not-exactly-flawless Schrauwen men elsewhere in the comic, which really does underline the running theme of masculine failings throughout Parallel Lives.

MATT: The constant antagonistic narration is also a springboard for some great humor. The “revelation” that all the friends Ooh-lee’s talked into watching her performance are only there because they want to see her fail spectacularly in public is set up and written perfectly, daring you not to snicker at it.

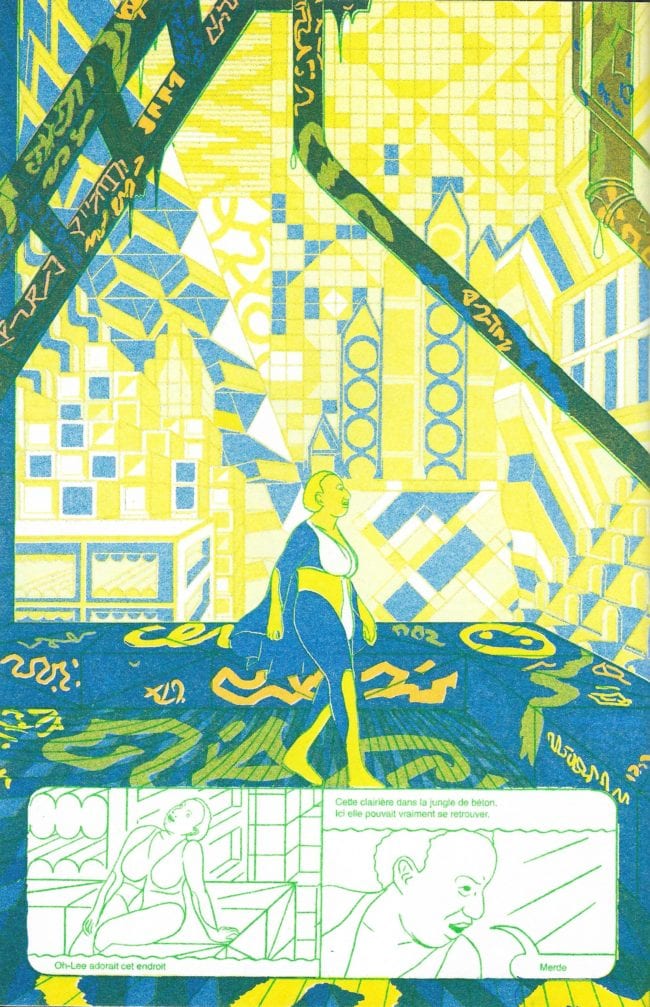

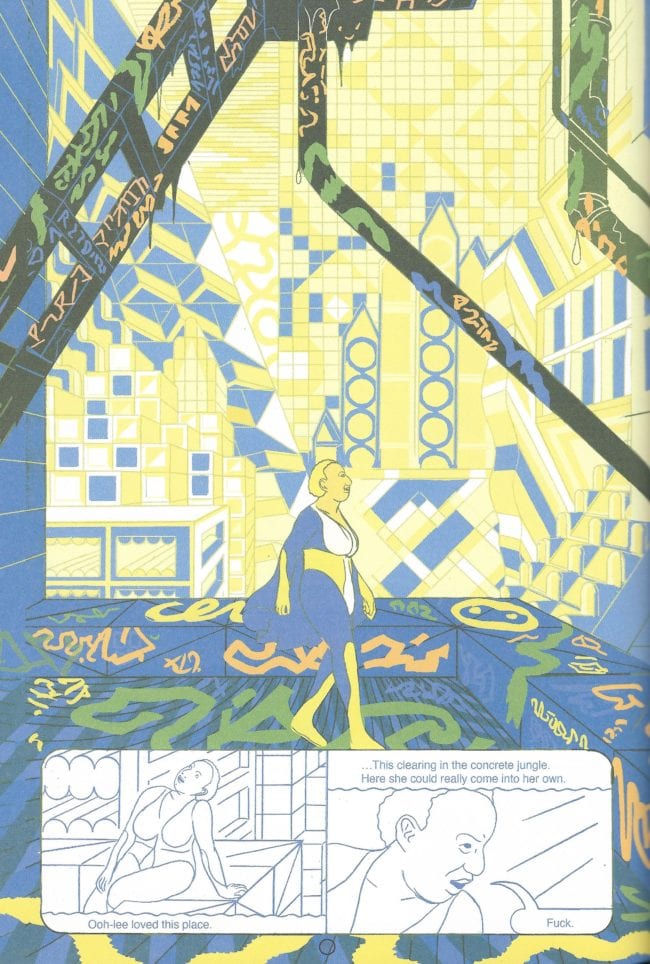

JOE: Ooh-lee’s interiority, meanwhile, is only occasionally expressed through snatches of spoken dialogue, or maybe allusively, through the unusual coloring scheme of the story, in which color fills vanish for several panels at a time, leaving monochrome line art. Maybe this is her emotion. In the Gouffre version of the story, the filled colors were riso-printed in a very luminescent style, so that the colors almost glowed - this stood in contrast to the monochrome line art pages, which sometimes presented only a few elements of the panel in ‘glowing’ style, to signify the presence of holographic characters (essentially ‘online’ in the story’s metaphor). Such special effects are absent from the Parallel Lives version, as Fantagraphics was presumably not inclined to riso-print however many thousands of copies, though the reader can still discern the rush of sensations upon the heroine when she backs away from communication and moves experientially through space.

MATT: Even without those crazy colors, Schrauwen creates a concrete visualization of his characters’ future habitat here. I was struck again by Ditko vibes, but more so by how gnarly everything in Ooh-lee’s world looks. I think of Schrauwen as a very “clean” cartoonist - minimal figures, geometric shapes, little or no rendering and line weight - but he creates a very convincingly inhabited, run down future-tech world. My favorite part of this whole comic might be the neon graffiti tags populating the backgrounds of the street scenes: it’s awesome to see such bold markmaking qua markmaking hanging around the edges of such a crisply drawn work.

Schrauwen pulls off music-in-comics pretty well, which, yeah, is saying something. Alan Moore can’t even do it! Scat singing is a smart choice of musical idiom to use in a comic book, given how verbal it is, and how frequently it eschews the established Western harmonic and melodic structures. The ending of this comic reminds me a little bit of the part in “Cartoonify” you mentioned where roiling emotions are solved by the flicking away of a cartoon teardrop: our heroine uncovers the identity of her tormentor and calls him out in a crowded karaoke bar with all their mutual acquaintances as witnesses. In real life, as we’ve learned in agonizing detail the past couple years, that would hardly be the end of it. But the sequence, and the tear snaking down Ooh-lee’s cheek as she does her best Scatman John, feel earned as a narrative climax. Yet I don’t want to overstate the emotional tenor of this comic. It still operates from a remove, studying more than attempting to impart its characters’ emotions - and trying to make you laugh at them above all.

*

Mister Yellow (previously published in the anthology Dome by Lagon Revue & Breakdown Press, 2016)

MATT: This is the shortest and maybe the strangest story in Parallel Lives, a shaggy dog that’s downright wooly. The circumstances of its creation might have something to do with how random it is: Dome was an event-specific anthology jointly created for the Angoulême comics fest by Breakdown Press and Lagon Revue. It features comics by the editors of Lagon and a number of Breakdown’s stalwarts, with Schrauwen and Simon Hanselmann sticking out as the creators whose overall catalogs have the least to do with the publishers involved. Dome is a large, short book, and while most of its other participants’ stories are necessarily light on narrative, Schrauwen breaks out the shoehorn and crams more onto two pages than I’ve seen since the giant-size issue of Kramers Ergot. “Mister Yellow” is rendered in absurdly dense 70-panel grids, continuing the trend of Schrauwen squeezing way more story out of way less real estate than anybody should be able to.

The plot is almost stream of consciousness, meandering from point to point with the bare minimum of logic necessary to maintain a narrative. It concerns a string of highly unusual events befalling one Olver Schrauwen, seemingly a citizen of the present day. An encounter with a mysterious yellow-garbed, yellow-skinned man leads to exotic animal sightings, a hospital visit for Olver’s poisoned son, a new set of lounge furniture, an act of heroic violence, and (perhaps) a healthier marriage and an increased appreciation of life. This is a story that passes by in front of you more than acting on you - “dreamlike” is overused as a descriptor, but it really fits here. The events described all make sense, more or less, but they don’t really fit together into anything sensical, anything you can take away from it after reading. This isn’t a knock on “Mister Yellow” - quite the opposite. It’s a comic that isn’t really like anything else; even in this book of weird shit it’s a bit of a sore thumb. I tend to remember individual tidbits of the story more than its overall shape. Olver’s son saying a poison dart frog looks like a candy; the way Schrauwen draws his hero running with completely stiff, straightened arms and legs; the casual grace with which the red and yellow two-tone printing is manipulated.

JOE: I have a real galaxy brain take on this one, Matt, buckle up.

One of the many ways in which my mind has been ruined by reading Chris Ware comics since I was a teenager, is that when I see a huge number of tiny panels on the page, I immediately think about time. I suspect anyone hardy enough to read this far down can picture any number of post-Jimmy Corrigan layouts by which Ware demonstrates the generational qualities of families (or locations, or whatever) by spatial means. One tiny panel links to another tiny panel linking to clusters of larger panels, with the reader sitting in a sort of God’s eye view of things, the comic’s point of view pulled back so far that the inhabitants of Ware’s comics are isolated in the panels, every moment in time frozen like a film strip and pasted together with other strips and excerpts to collage a statement of being.

JOE: Schrauwen has mentioned taking inspiration from Ware in the past, and Ware is on the record with his admiration for Parallel Lives (“a series of funny and frightening psychosexual ruminations on the nature of relationships that feel as fresh and strange as human life actually is”), so let’s apply these qualities to “Mister Yellow”. Reading the story, I’m impressed by how stuck in his own mind the protagonist, Olver, seems to be. He’s paranoid about his wife’s fidelity, interpreting extremely innocuous behavior as evidence of the alienation of her affections. He frequently neglects his son, leaving the kid to go through an entire school day holding the broken zipper of his pants together, and later ignoring him (possibly for hours) as he lays on the floor vomiting. He drops $300 on a ‘free’ lounge suite, redecorating the house without telling anyone, and when he wife leaves in frustration, he immediately takes it as conformation of all his suspicions about her. He’s as self-absorbed as Oly from “Cartoonify”, with the old-stock, un-futuristic masculine outlook of Armand from “Hello”; he wants to beat the shit out of every threat to his home.

MATT: And don’t forget he loves his vino! He destroys three bottles in about a day and a half by my count.

JOE: In other words, he is stuck in chronology, as trapped by his own perspective as he is physically trapped, frozen by the tiny panels of the page. This is the engine of the plot - everything Mister Yellow shows him, he misinterprets: a poisonous toad, Olver thinks is a fun pet; a psycho on the loose, Olver thinks is his wife’s lover. In fairness, Mister Yellow, who seems to flit in and out of time, is not very clear with his warnings, but you’d think the guy could pick up on a pattern eventually; Olver cannot, eventually luxuriating in the heroic satisfaction of Saving His Family… at which point Schrauwen springs the punchline, which is set up all the way back in the first tier of panels. Pity Olver, who cannot see outside of time! He is a prisoner of the grid, which is his era.

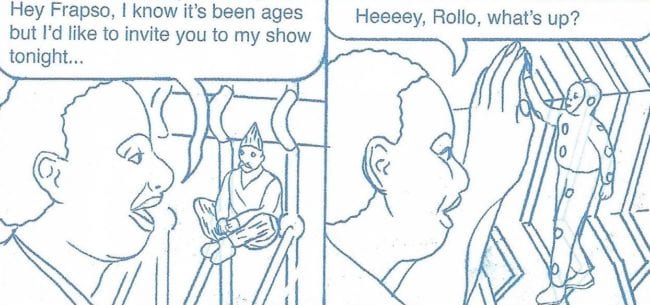

MATT: Here’s something you might find interesting, Joe: “Mister Yellow” as reprinted in Parallel Lives isn’t necessarily the complete story. Dome featured a 4-page “centerfold” that reprised each of the stories the book collected with daily strip-format epilogues. In Schrauwen’s, a blue woman wearing a brooch or button identical to the one Mister Yellow wears in the middle of his chest materializes next to a doofy looking dude at a bus stop and the two stare at each other silently for a few panels. So the comic’s reality itself, as originally imagined, isn’t even a prisoner of its own grid, or the pages on which that grid is printed - use your fourth-dimensional perspective, flip over a couple leaves, and there’s more! Olver Schrauwen, however, is nowhere to be seen in the story’s enigmatic coda, which I think tends to support your conclusions.

JOE: Ahhh, it’s the Twilight Zone! I’m a big fan of ‘definitive’ editions of works that actually cut things out.

MATT: Honestly, I think my favorite thing about “Mister Yellow” is just looking at it. Especially as it’s printed in Dome, on big 11”x14” pages, it’s a pretty amazing visual work. I like spreading out the book in front of me and letting faces, cars, figures swim out from the assortment of red-yellow postage stamps clumped neatly together into what looks like a comic-book version of a half-done Rubik’s cube. Schrauwen’s no-fuss style scales down well, never anything but perfectly legible despite the fact that he probably had to keep a microscope handy when he was drawing this thing. Simply drawn yellow characters and all, it feels a bit like a visualization of an unusually imaginative kid’s epic Lego play session. Equally impressive is how Schrauwen tells a story without being able to get more than ten words or so into each panel, and the way he manages to vary the compositions of his pictures within their tiny frames enough to avoid visual tedium - a lesson plenty of “serious” cartoonists drawing at normal size would do well to heed. “Mister Yellow” is merely good, while some of the other stuff in Parallel Lives is legitimately great, but it speaks just as clearly to the depth of its creator’s very unique talents.

JOE: I laughed really hard at the final bit in this one - guys hitting their head is always funny. But pay attention to how many times guys get hit on the head in Parallel Lives: it happens to Oly, Olver, and another guy in the final story, at which point this most fundamental of slapstick gags becomes a punctuation at the end of the sentence of men facing a future agnostic to their obsessions... which is how I see the message of this book.

*

Space Bodies (created for Parallel Lives, 2018)

JOE: And so, we come to the final story of Parallel Lives, which actually takes up about half the book.

MATT: If the dense short stories reprinted in Parallel Lives are albums-as-anthology shorts, the original bonus cut “Space Bodies” is an album proper - 64 pages, with plenty of big splash panels and full-page drawings. Good thing, too! This, for my money anyway, is by far the best looking comic Schrauwen has ever made. As you mentioned, the other comics in this book are printed at a significantly lower wattage than in their day-glo, risographed original forms. This one starts with the same muted hues, a CMY coloring approach that reminds me of John Pham’s "Deep Space". But halfway through, as the story’s intrepid crew of space adventurers lands on an alien planet, it explodes into a lush bouquet of pastel tones, bathed in overlapping washes of pale, luminous digital gradients. Schrauwen hasn’t made work this colorful since The man who grew his beard., but while it in that book it looked pop-arty and purposefully naive, here it feels like the sun coming up. The drafting, too, is noticeably subtler and more elegant than anything else we see in Parallel Lives. Reading the first half of this book it’s easy to forget how visually stunning Arsène Schrauwen was because of how tightly everything in the pictures is packed. In design and drafting, “Space Bodies” approaches a Curt Swan level of casual naturalism. The story too feels a bit like something Eisenhower-era Superman editor Mort Weisinger might dream up if he, like main character Olivier Schrauwen, were cryogenically reanimated 200 years from now.

MATT:Yes folks, alien abductee Olivier Schrauwen of “Greys” makes an encore appearance as the protagonist of the far-flung space opera that closes Parallel Lives. To open the comic, he addresses the audience, saying that the very act of telling a story about himself is a “return to an archaic notion of the self…” In the future that “Space Bodies” forecasts, by far the most developed and most utopian vision of things to come in this book, the idea of individual identity is largely a thing of the past. “In the end, we function like organs in a body; our individual qualities are useless,” says Olivier’s friend Bo, a native of the future rather than a transplant. Indeed, Schrauwen and his team of astronauts function as “experiencers”, taking in the wonders of the cosmos for the benefit of the terrestrial population, who presumably see no difference between the experiences of others and themselves.

Does that sound a little like being an Instagram influencer to you, Joe? The very first thing that jumped out at me about this story was that Schrauwen was making a comment on social media, and sure enough, a few panels after explaining his job, he basically describes the act of storytelling as a form of social media (the first?). Certainly, spinning a narrative plot is just as much “creating a persona” or “making yourself someone else” as, say, catfishing is. I remember riding the L train back from Comic Arts Brooklyn together with Schrauwen and yourself, and asking how much of the then-recently released Arsène Schrauwen was based on his grandfather’s real life. Would I ever have asked him the same question about Ooh-lee Schrauwen? Yet both are equally fictional: “experiences” sent back from one man’s brain for the brains of many to enjoy. If “The Scatman” treats of social media’s dark side, “Space Bodies” describes an almost identical phenomenon, the technological erosion of one’s sense of selfhood. But here it is presented as cause for celebration.

JOE: Well, that’s an ideological character of utopia. Some of the political discussion happening now in the United States concerns the notion of individualism as conservatism, demanding a recalibration of the U.S. perspective towards social good; individualism, of course, is so baked into the U.S. concept of the self, it typically goes unquestioned as to its political character - it’s as neutral as the sun shining in the sky. Schrauwen was born in Belgium and lives in Germany, and probably has a different perspective… Ooh-lee, for example, lives in a society where economic needs are met by the government (or whatever is running the show) on a flat basis, and her economic disadvantage stems, we’re told, from her own desire to live beyond the normal lifespan that the society is prepared to cover. Had those ideas come from a U.S. writer, it might seem like libertarian advocacy, like a dire warning of our direction, but Schrauwen treats it as just another step in a gradual evolution, which the Olivier in the story accepts readily.

MATT: Schrauwen is doing sci-fi on its most basic and essential level here: politics aside, his projections feel less like fantasy than forecasts of conditions humanity might actually be moving towards. I’ve been repeatedly surprised in recent years at the vehemence with which people ask me to post pictures online whenever I tell them I’m going on vacation, equally so at my own excitement when I see someone else’s posts from a place I wish I could visit. Few people’s experiences are their own sole property these days, and most of us seem to find some enjoyment in that aspect of modern life.

There’s another leap the world of “Space Bodies” makes at some point in the next 200 years. It’s probably a necessary one on the road to a truly communal consciousness: the almost total destruction of gender as a social construct, and binary gender itself by extension. The species is perpetuated through unmentioned technological processes; at one point Bo says that she can’t imagine the possibility of someone having a personal relationship with their biological parent. (Imagine if you had to be best friends with the assembly line worker who put together your phone!) The gender gap closed by hormone treatments, characters seem generally unsure of one another’s gender identities, and entirely unbothered about them. Physical intercourse as a medium of eroticism is out; instead, people use a “sexotron” (lololololol), where a group of people’s “individual bodies become one supercharged erogenous entity… operating like an orchestra that joins in a majestic, symphonic buildup, culminating in a crescendo of profound pleasure.” Everyone has access to pretty much everything, it seems. And so the kind of toxic masculinity this book foregrounds in other stories -- the drawing of a sacrosanct magic circle around the people, things, ideas, experiences, and self-image that a man believes he deserves unmitigated access to, often at the expense of the well being of others and sometimes the individual himself -- has become a thing of the past.

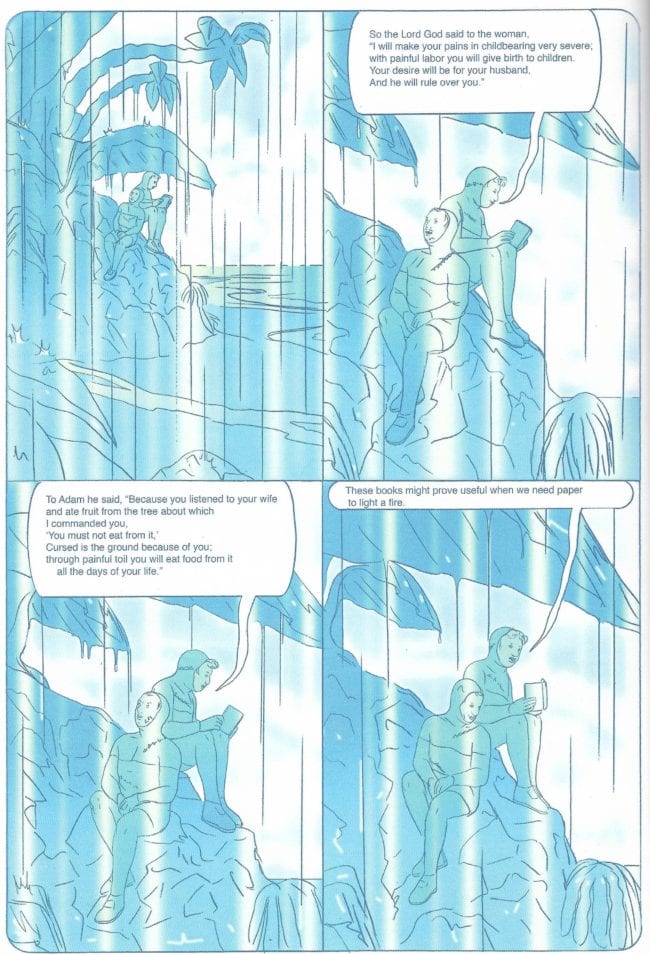

Or has it? Like any good comic book villain, the dreaded nemesis that dogs the Schrauwen clan through time and space begins to narrow its focus on Olivier once he begins the story of his own experiences as an individual - inevitably privileging himself. The Olivier of the 21st century bequeathed a box of treasures to be taken with him on his journey to the future, textual totems containing the germs of the contagion that time has wiped away: a Tarzan comic, a Bukowski novel, a Bible, and a hardcore porno magazine. These are treated by all as hilarious, baffling artifacts of an unfathomable past. But a series of technological failures besiege Olivier and Bo’s spacecraft and their technologically calibrated hormone balance succumbs to their own rude biology. Soon they are stranded without food or shelter on an inhabited alien planet, and the ancient texts, taken together, provide a blueprint for a brutal brand of survival. More and more illogical tics of behavior are attributed to rising testosterone levels in Olivier and estrogen in Bo, physical sex is somewhat anticlimactically rediscovered, and an attempt at first contact with the planet’s inhabitants goes disastrously awry in a manner anyone who’s read their history will recognize. The characters retain enough of their culture to burn Olivier’s books for fuel after a reading of the Original Sin story, but nonetheless they end up living a gender-bound Robinson Crusoe existence, with a now-bearded Olivier going out each day to fish for dinner and a long-haired Bo minding the crude house they’ve constructed.

Then Olivier comes up for his turn in the parade of whacks on the head you mentioned earlier, and is killed by a falling coconut in the most absurd example of the punchline yet. Immediately, Bo is saved, recovered by the rest of the crew that’s been searching for her all this time. Olivier, the Last Real Man, is left moldering and utterly alone on the beaches of an alien world. The spell woven by the past’s stories of its own glories is broken, presumably for good.

JOE: Reading this story, I was reminded an older French album: 1988’s The Gardens of Edena, where Mœbius presented these two sexually indistinct characters who land on an Edenic planet, and by consuming natural foods recover ‘male’ and ‘female’ characteristics - the man, though, tries to rape the woman, and she leaves him, and then he undergoes a whole vision quest full of captive princess imagery, and he fights a huge kaiju… there’s an element of examining possessive qualities and the fear of abandonment on the part of the male protagonist, though it’s also very clear that Mœbius is advocating for a ‘natural’, rather conservatively gendered state.

“Olivier Schrauwen” in this story, meanwhile, is comedic for his general inability to fit in. He’s much whiter in skin tone than anybody else on the spaceship crew, and his fascination with the past of his origin is treated as a sort of lovable eccentricity by the other characters - a very touchy-feely group, always embracing one another, thinking nothing of pulling out their genitals, everyone having Future Sex with everybody.

MATT: In reading “Space Bodies”, I was struck by how pointed Schrauwen’s literary criticism of the texts Olivier has brought into the future with him was. We’ve talked a couple times about how uninterested this author seems in rendering judgment on anything, but boy do the Killer B’s of Bukowski, Burroughs, and Bible brave a bashing here! Using the incremental form of comics, Schrauwen shows how the cultural artifacts of an imperfect, inferior past can infect the host body of a present that’s moved past any practical use for them. It’s almost like Schrauwen is trying to create a text that will undo some of the poisonous program that books like these (and David Deida, and Jordan Peterson, and The Game, and superhero comics, and and and) have created. Like he’s trying to put forth something unique and tantalizing enough in its depiction of what could one day be possible that it changes the way its readers think about their own lives. That’s the point of telling stories, right? That’s why we think about the future, isn’t it?

JOE: There’s a lot of melancholy here, though - more so than with “Hello”, or anything else in the book. Unlike Armand Schrauwen, Olivier is totally welcomed by the new society, but still he fixates on the arch-masculine author god archetype of Bukowski, whom he imagines himself to be, though he probably never fit into that gendered designation either.

The thing is, Schrauwen is both parodying these texts, and also showing their embodiment in the future, through Olivier's eyes. The whole encounter Olivier and Bo have with the alien natives - it’s a Tarzan comic, like the one Olivier reads (student of colonial literature he is). They discover a lost civilization, fight a big ape, swing on vines; there’s a creature they very self-awarely name Cheetah. In this way, the book reverses the situation of “Hello”, where the future society is informed by the past in small, ephemeral ways. Now, Olivier witnesses the situations of these books echoing in the future, and they act to bind him to his own past.

JOE: It’s wistful, isn’t it? How he narrates the amazing sights of the future, but how these sights are freighted by his own interests in a past art and culture, so that we can’t entirely see them with his authorial intervention. This was a big theme of Arsène Schrauwen too, but the focus of Parallel Lives on the behavior of the male characters - it’s not so surprising to me that this one is attracting a little more generalist book world attention, because it’s a bedrock literary topic: men like this, thinking about themselves, or versions thereof.

MATT: “Space Bodies” points up a very strong through line in Schrauwen’s work: the damage wrought to human beings by systems of control. The man who grew his beard. looked memorably at the plight of schoolchildren (or were they mental patients? Or both?). Arsène Schrauwen, to me, was a rendering of the European colonial project as the ultimate absurdity of concept. To clearly achieve this rendering, Schrauwen simply deleted the elements of atrocity that accompanied the absurdity when it went from concept to practice. Arsène focused on pointing up the inherent flaws of a cause, perhaps hoping to inform the reader’s interpretation of that cause’s effect. There’s an argument to be made against doing this, but I think that book is the most eloquent speaker in its own defense: it zeroes in to render its subject as both hopeless and useless, without imputing to it the elements of glory that our culture primes us to see in all tales of conquest. Instead, it follows Arsène as he traverses the softer, more harmless edges - unrequited love, a yearning for achievement, fear of the unknown - of the same toxic masculinity that forms Parallel Lives’ antagonist.

This book grapples with darker aspects of that toxicity, painting them onto the blank canvas of the future rather than a past or present utterly in thrall to them. But it doesn’t leave the effect to your imagination: it illustrates how benighted and dangerous the scripts our society is running can be. It’s almost like introducing a foreign culture (ha) to a petri dish and watching as it turns everything to slime mold. In the cold, clinical light of tomorrow, our culture’s masculinized, individualistic ideal of selfhood is again pictured as a total absurdity. Schrauwen’s authorial eye stares at it with utter bemusement before ultimately leaving it in an appropriate place: dead and very far away.