DARWYN’S EVOLUTION

NASO: So we talked a bit about your first work, the New Talent Showcase, and how you went to New York and sold that. But you didn’t really get comics work until 15 years later. So what happened?

COOKE: Well, like I said, back in that time there was no FedEx or e-mail or FTP sites or anything like that, so it quickly became apparent that I could not really make a living doing comics unless I was New York-adjacent. That led to art direction and design and that was something I pursued wholeheartedly for several years. What happened was, in my very early 30s, I finally took stock. You slow down a bit and go, “What the hell am I doing, why am I doing it, and is it what I want to do?” The answers to these questions did not make me very happy. I was doing advertising, and I wanted to do more with what I had. I had a lot of different avenues open to me, I suppose, at that point. Looking back at when I’d last been really happy, before life complicates your life, I had to go back to those summers when I was a kid, thinking, “I’m going to be a comic-book artist.

So I thought, “You know what? This is probably my last chance to take a shot at this. I was worn out from the work I’d been doing and the way I’d been carrying on, so I took a break and that’s when I put the pitch for [Batman] Ego together. So this would be like ’94. I go to a Chicago convention. Again, like I said, in my life when I’ve wanted to do something I’ll just do it and then take it wherever I gotta take it to show people, and figure it out from there. So I get down to the show, and of course, this was the year of the big Image boom. So I’m the last thing in the world anybody wants to actually buy, a guy who draws like Alex Toth! I couldn’t have picked a worse time.

NASO: Yes … Liefeld you are not [laughter].

COOKE: Oh hey, I can remember at that show, I was in line with a girl who was a colorist, I was just chatting her up and hanging in the line, the line was for Will Portacio and he was doing portfolio reviews. He looked at my work and he [laughter] was trying to explain to me how to do the kind of work they do. It was a bad year for me to be out there with that stuff.

NASO: How did you react to that? Was he just trying to give you advice?

COOKE: Yeah, he was being earnest. He didn’t realize I’d made an aesthetic choice away from what he was doing. He thought what I needed was to have my eyes opened to the way they did it, whereas I had decided to avoid that approach. What does he know about that? I think all commentary or response to the work is good. These days it’s hard for me to get honest commentary because it’s coming from people who know me. You rarely get to hear what people really think of the work, unless it’s the odd reviewer.

I met Archie Goodwin, and I did show him the work. He said, yeah, you do a nice Year One Batman. But it didn’t go anywhere. The next time I was in New York I went by and dropped it with the DC editors, Denny O’Neil and the head of the group and the time. There again, they were sort of complimentary, but they couldn’t see any place for it or anything to do with it, so it basically died. I said, “OK, well, that failed. That was my life’s dream and I failed. Fantastic.” I went back to being an animator for commercials and trying to figure out what my next step would be, and that’s when the Journal ad came along. So here’s where the story gets convoluted, because now I’m working for Warner Brothers. And one day — this is like, three and a half, four years after I pitched Ego — the phone rings. “Hi. Is this Darwyn Cooke? Yeah, my name’s Mark Chiarello at DC Comics. I’ve got this thing, Batman: Ego. I found this here in the office, I was wondering, would you still be interested in doing this?”

They had hired him as the art director at DC and when they gave him the office, he was clearing out all the old pitches. Throwing them out. And he found the old pitch. And he liked it. So people ask me, “How do you get started?” And I just laugh and I go, “I don’t know! Hang-glide off of the Chrysler building. Try voodoo. I don’t know.” For me it was a really strange way around. So at that point I was working on the shows, and I said, “I’d love to do the book, but I’m really busy working on Batman for Warner Brothers right now!” And when I decided that I had had my fun with animation, that’s when Mark and I got together and I started Ego.

NASO: Were you commissioned to write and draw it from the very beginning?

COOKE: The pitch made it pretty clear that I would write and draw both and it had a comprehensive outline, and I had done 12 illustrations to go with the outline that would show my abilities.

NASO: It must have been important for you to establish yourself as a complete creator. Is that something you wanted to go into comics as?

COOKE: At that point, I decided to leave L.A. and what could have been an incredibly lucrative career, I think, in television animation and the like, in order to pursue comics. At that point — this was very conscious, very deliberate, I’m very goal-oriented when it comes to these kinds of things — I made a decision right then and there. I was not going into this at entry-level. I came in as a writer/artist so I had enough influence to decide what I was doing and how I was doing it. I would live or die by my own ability and whether I could get it right, because I didn’t feel like I had years to spend breaking in and working my way up.

At that point in time, I was 37, and the clock was really ticking. I looked at all the experience I’d had up until that point, and I saw the amount of time that gets consumed if you go about things a certain way. So I decided I am going to go at this full-on, from the point of view that I want to do it right or I don’t want to do it. I’m sure I know what that means to me and as long as that’s understood, then I want to go forward with this. The minute it’s no longer any fun, I’ll go back and do something else. This is the thing I want to do right, and not compromise on.

NASO: So did you go into Batman: Ego thinking you were going to commit to comics and this was going to be your career.

COOKE: Absolutely. I made the decision that animation had been fun, but I wanted to narrow the circle so that I could express more on my own. I’m not going to call it a vision, because up until this point I’ve done work for hire on licensed characters and I don’t want to be pretentious about what it is I do. But I knew that I was going to be happier if I was able to construct the whole thing myself.

NASO: Why did you decide to write a story about Batman pondering the concept of justice after he indirectly affects innocent people?

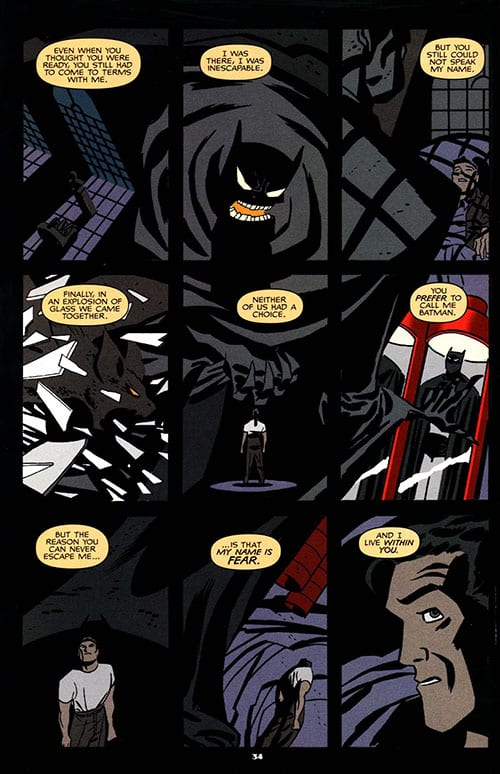

COOKE: It’s probably one of the strangest inspirations. There’s a movie called My Dinner with Andre, which is an independent film about an evening at dinner, with this guy… named Andre [laughter]. It’s not clear from the title, but it becomes apparent over the course of the movie [more laughter]. That’s really the idea: What if these two guys could sit and have a conversation? Are they the same person, just with a mask, or are they really two different personalities within the same person. He is, psychologically, one of the more fascinating super-jocks. There’s a lot more depth to this guy than there is to … some of them. So I thought, what if they could actually sit down and talk about all this stuff they do, and what it means to them. Of course, they can’t actually do that because they’re the same person, but I thought, it can happen in the theater of the mind. The question is, what event would bring them to that point? That’s why the book opens with him finding out he is responsible for a guy killing his own family, and then killing himself. He sees that his actions have these repercussions that he hadn’t expected, and that creates what I’ll call the “mental environment” for the story and where it takes us. I remember the idea was, I want to do something that hasn’t been done before, which is a tall order with this character. I wanted it to be something that looked at his career in an overview so that I got the chance to draw all the stuff I wanted to draw in case I never got to do it again. That’s why we see almost every facet of his career through their conversation. It allowed me to draw the Joker, Catwoman, his origin, the scenes with Robin, Two-Face at the drive-in. All of those images could very easily be incorporated into the framework of that story, so it was a great fit.

NASO: When the book came out, what did DC say about it?

COOKE: Not much. I think they thought I had promise. I was totally unknown. My editor, Mark, was the guy who made it happen. The book was well received and it sold OK. At that point, internet reviews didn’t happen. This is right before all this fad exploded, so you weren’t able to gauge response the same way you are now. But as soon as it was done, I was talking to Mark on the phone one day, and he said, “Well what do you want to do next?”

And I said, “Well I don’t know. I haven’t thought about it, really. What would you guys like to have me do?”

He said “We were talking about having you do a Justice League thing.” This is 1999, and Grant Morrison was burning up the charts with Justice League at that point. So Justice League is hot. That’s DC; if Justice League is hot, then they’re pushing that stuff, activating projects and so on. Grant’s successes with Justice League led to them saying to me, “Why don’t you do the Justice League?”

I didn’t have any real affinity for that, to be quite honest, but again, you know, “Wow, OK, wow, the Justice League!” I was surprised that they would want me to consider working with those characters. I sat down to the task of it and in relatively short order, I realized that the only thing that interested me was who they were before they became the Justice League. That was the only place there was room in their characters to tell a story, everything else had been covered to death. We were also at a point where a lot of the characters had been dragged through the mud, and I realized that I didn’t want to deal with all the continuity that had been heaped on them. I thought, well one way to do that is to tell a story in the past, before all that shit happened.

NASO: So you came up with that idea, and then did they run with that?

COOKE: Ha! [Laughter.] That’s what I mean: I’ve got the longest start to a comic career, I think, on record. The New Talent Showcase at 20. 37, 17 year later, comes Ego after sitting around for four years in a pile, and now we start on The New Frontier. Once I pitched the actual idea of putting it against the real history and time, at that point what came back to me was … something at that stage had to go through every editorial group for approval.

NASO: How many groups were there?

COOKE: You had a Superman group, a Flash group editor, a Batman group editor, and Wonder Woman group editor …

NASO: So any character that appears in this New Frontier …

COOKE: … the editor has to sign off on it before it happens. It doesn’t work that way anymore, but this is how it worked at that point. So it goes in. Two or three months go by, what comes back is, “OK, but with Black Canary, not Wonder Woman.” That all got ret-conned. So we can’t do Wonder Woman in the story, it’s got to be Black Canary. And on and on it went, all the way down the line. They wanted me to observe continuity as they had established it, and everything that was happening that month, and I was very resistant to that. We spent about a year trying to take that story and make it make sense within the framework of the continuity. This went back and forth and we finally got an outline together that made the group editors happy, and then when Paul Levitz read it, he actually phoned me — I hardly ever talk to Paul — but he says to me, “What happened to that wonderful story?” [Laughter.]

The thing is, you can’t really say to the man — in hindsight I can say it now, but back then, it’s not like I could say to him — “Your editors happened to it! I’ve been waltzed all over the ballroom and even taken out behind the barn.”

NASO: But he must have known. He must have realized that.

COOKE: Well, I just explained that I’d been asked to pull it into continuity and at that point Paul made a big move and he just said, “Look, ignore the continuity, I want the story that you pitched. You tell the story that you were gonna tell and don’t worry about continuity.” From that point on I had my heels dug in. If the publisher tells you that and then you let somebody that works for the publisher tell you otherwise, then you deserve to get screwed. You’ve just been told by the Man. So from that point on my heels dug in. They always saw the merit of the project, but they always wanted it altered in some way that I couldn’t abide by. So I would say, “Nah, let’s not do that.”

NASO: So once he told you that, how did you approach the editors, or did Paul tell them, “Listen, I want Darwyn to do the story he originally intended?”

COOKE: It’s easy enough for him to say that, but then there’s the physical day-to-day experience of working and getting along and all that stuff. And nobody is paying you for all of this development. Paul did something really great at this point. I had spent a lot of time getting back to square one, and I was pretty frustrated about it all, and Paul advanced me money. They hadn’t seen a page of this book, and he advanced me what I consider a really great amount. That gave me the confidence that he really wanted it and that he was going to put it together. So I thought, “OK, I’m going to have to wait this out until we can get it right.” It had also been planned to be as long as it was, and that’s the point at which I said to Mark, my editor, “look, before I go down that road, what I would like to do is this little book called Selina’s Big Score. We’ll run this one through and we’ll see how it goes, and if it goes smoothly and it works out, then I’ll know,” because the commitment in time on New Frontier was going to be enormous, and there’s other ways to make money. If it came down to spending all that time just to make money, well, there’s better money to be made. So I had to know that it was going to be what I wanted it to be before I was going to commit that time and effort. We did Big Score, and that only took 18 months to get approved.

NASO: But didn’t your Catwoman stuff come out before Big Score?

COOKE: Yeah, it did. All these things are happening tangentially. They overlap. Catwoman came up shortly after New Frontier had been pitched. And it was like, OK, I can do four months on Catwoman but then I have to start this big project that I’m gearing up for. So as New Frontier got caught up in going through all these approvals, it became clear that I needed to do some other stuff to make some money. And I came up with the idea for Big Score as Ed [Brubaker] and I were doing Catwoman. That was in the mill, knocking around there.

NASO: So, the re-launch of Catwoman … were you in on developing that series from the beginning or were you just assigned to draw it? How much input did you have on the new direction?

COOKE: I think with Ed and I, that it definitely became Ed’s book, because he stayed on, but over the course of the four we did it’s a pretty even split. We’re both pretty proud of that stuff. It was just terrific; it worked out really well. I did have an affinity for her because she’s an amoral character. She’s a lot easier to understand than a hero or a psycho. She’s a lot more human than most of the characters. I think the way it worked out was, Ego had just come out and I think Ed thought it was pretty cool, so he approached me about it in San Diego. I was reluctant because New Frontier was just about to pick up. He asked me to do the first arc, and I said, “If I can redesign the character, and you realize that I’m hoping to bring more to the table than just penciling out a book, then yeah, I’ll get involved.” And they were happy to do the redesign.

NASO: She needed it; it really breathed new life into her.

COOKE: When he mentioned Catwoman I thought, “No, absolutely not,” because I’m thinking about the Catwoman that I see on the show. And again, I don’t care where people get their jollies, but really. I feel my work reflects a definite point of view regarding women, and their strength and their sexuality, and what Catwoman was at that time as a character … I knew I couldn’t be associated with it if that’s what it was. It’s just not what I’m trying to put out there. So the redesign was essential, and hearing Ed’s concept for her as a character let me know that that was not the road we were going down.

NASO: Were you familiar with Ed’s work, or did you know Ed when he approached you?

NASO: Were you familiar with Ed’s work, or did you know Ed when he approached you?

COOKE: I had read Scene of the Crime, which I thought was pretty good. That was the Vertigo miniseries he had done. I hadn’t read Low Life at that point, and Ed, at that stage, was doing Deadenders with a studio mate of mine, Cameron Stewart, who was inking Warren Pleece. This was Ed’s first foray into what I’ll call the Superjock arena, Catwoman was his first cut at that kind of thing. So it felt like a great fit and an exciting thing to do, because he had new ideas in terms of what he wanted to do with the character, and I saw it as a real opportunity to do a positive female character that maybe women would enjoy reading about. So, yeah. I really got into the redesign, and what we did with her, and fleshing out her world and Slam. Ed and I … it was rocky while we were doing it. I don’t think that in hindsight, either one of us has a problem with the work when we look at it, but I think from a process point we cut each other short. I don’t think we were quite on the same page with certain things. I would take portions of certain scripts and sort of run with them in a different direction that added subtext. I would never change his dialogue, I would change staging or pacing elements.

NASO: What did he think about your changes?

COOKE: I think that at first he was really taken aback that I had done it, and I really tried my best to explain storytelling as we’d learned it down at the Warner Studio, which is that you take the script, and then as the board artist you’re basically directing that sequence, and that’s the comic artist’s job, too, really, to direct the sequence that’s been written. Any good director, if he feels the staging can be stronger in a scene, he’s going to restage towards his theme. That’s his job, that’s what he brings to the party, and that’s what collaboration is all about. The question is: You have to have enough control and understanding of the writer’s intent to make sure that when you’re doing that, it’s all feeding into his theme and what it is that you’re trying to get across. I think in many ways we were a really great match because he was so skillful at creating that world she lived in, and the characters. What I was doing was trying to find cinematic and fresh ways to energize what was basically a really dialogue-driven book, disguised as a supervillain comic. I was going through Ed’s script, going, “This is all really incredible stuff. My job now is to bring kinetic to it.” The characters are there, the drama is there, the dialogue is there. It’s all there in spades. So what the hell am I here to do?

I think it worked out for both of us. I think we both picked up a lot from each other. The one character we really bonded over was Bradley, Slam Bradley.

NASO: Talk about how Slam came up because that’s an old character that hadn’t been used in a long time.

COOKE: Yes. When I sat down to do the Catwoman redesign I ended up doing the four covers for my issues all at once, and coloring them and sending them in, because I wanted them to see the cover design; the whole thing was a package. They were already really thrilled with the direction Ed had picked and what we were doing. Then when they saw the covers, they decided to relaunch at #1 and scrap the book. So they built in six months worth of the original run before we started up, and then they came up with the idea, how about a backup series in Detective? Ed phoned me about this, and he was excited. He said, “We can have a detective trying to find her.” Because she’s presumed dead at the end of the old series, so we could have a guy out to try to find out if she really is.

And I said, “Yeah, that sounds like fun.”

And he goes — and this is the cool part — “So here’s what I was thinking: What if we used one of those really old guys from the early detective comics?” He mentioned Speed Saunders and Slam Bradley. I know Ed was aware of them as characters, but he hadn’t actually read any of that stuff, and I had read some of it. And yeah, Speed Saunders is Harbor Patrol guy [laughter]. He was drawn by Fred Guardineer and it was a very stilted, very illustrative kind of strip. Slam Bradley … the first splash page that ever featured Bradley is the most un-P.C. thing I’ve ever seen. His shirt is ripped off Nick-Fury style, and he’s swinging a Chinese guy by his hair into another Chinese guy, knocking them on their ass. He’s this two-fisted brawler, and I said, “God, Ed, Slam!”

He took a look at it and he said, “Oh totally.” We both really clicked on that. That’s a character that I love working on. I know Ed does, too. I know he has a beautiful idea for a Bradley story, a graphic novel that never got made, and it would be fantastic. I hope he gets a chance to do that sometime when he’s back across the street.

NASO: So, you did Catwoman for four issues. Were you doing Selina’s Big Score at the same time?

COOKE: The way it worked out was, I came up with the idea for Big Score during Catwoman, and then pitched it in and 18 months go by. Time moves slowly [laughter]. So by the time I got to Big Score, to sit down and actually do it, my work on Catwoman had been finished and I had done some stuff at Marvel, a bunch of things while I was trying to get New Frontier going.

NASO: Like X-Statix?

COOKE: Yeah, I ended up working on X-Force and X-Statix and doing a couple of Spider-Mans. Things like that that were just honing my chops and keeping me going while we were trying to get New Frontier together. So yeah, Catwoman, then Marvel work, then Big Score. Then from Big Score we go to New Frontier I guess.

NASO: So why did you want to flesh out Catwoman’s back-story, how did that come about?

COOKE: [Sighs.] Let me tell you the truth [laughter]. I had the idea for the heist years ago. I’d come up with the notion of that type of a robbery, throwing the money off of a bridge into inflatable bags and boats, waiting. I had the gimmick for a long time. I prefer doing the crime stuff to the superhero stuff, to be quite honest. The Catwoman re-launch had gone well and I thought, man, we could fit her into this story really easily. Then I started thinking, what is this? Hey, this could set up where the series went, and that way I wouldn’t even have to worry about her costume. It could just be her. It went from there, and I just fleshed the book out with the characters I was comfortable with. The other two bad guys I had already drawn for that Batman story in Solo. And Slam Bradley, the rest of them, it was a real easy thing for them to plug in to this plot I had come up with.

NASO: This is the second big story that you wrote and drew. Do you think that you had grown as a storyteller since Batman: Ego? How did it change, the way you approached things?

COOKE: There was a big change, because Ego had been constructed in a vacuum, and it was meant to touch on all these different facets of a guy’s career. The structure was probably a lot drier. Big Score from the beginning was meant to play like a movie, like a great heist film, sort of a Rashomon thing going on there, because I used four different narrative points of view to help keep it interesting. I thought, if we hear different people narrating the book, it gives us different impressions of Selina as a person. But the big difference was that, by then, I had storyboarded a lot of stuff, and been able to consider and concentrate on how to translate certain parts of animation into comics. Write with less narrative, use more dialogue and visual means to get through a story. If I had to take a single thing I did that I liked the most, it’s probably [Big Score]. Certainly not the best drawn, by any means, but as a book or a story, it’s my favorite.

NASO: So animation is really what factored into how you were going to approach books after Ego.

COOKE: That would be oversimplifying to some degree because the animation was just the first real opportunity to put film theory into practice. As crazy as I was about comics when I was young, I was even crazier about movies. I had torn movies apart and put them back together in my head a million times. There was a lot of that that I was bringing to it as well.

NASO: You seem to have a really good grasp on Selina’s character, Catwoman. Do you have any more Catwoman stories that you’d like to tell?

COOKE: You always look at the stories you do and the characters and you think about what would happen next. There are two ideas I have regarding Selina. Whether they will ever see the light of day, I can’t really say. Maybe one day. Right now, I don’t see it in the immediate future, but I definitely know her well enough, in terms of who I think she is, that I know where I’d go with her. One of the most obvious things I can do is open a book with Gotham Harbor, and we see Stark coming up out of the water, holding his stomach, with all the bullets in him. Like in the beginning of Point Blank. You know, it’s comic books ... he’s not dead! [Laughter.] He’s back to settle up with her, once and for all.

NASO: That’s very movie-like!

COOKE: It is. There’s a movie called Point Blank with Lee Marvin, where he’s double-crossed at a robbery and shot in the stomach and left to die at Alcatraz, and then has to swim back with all these bullets in him. It’s about him exacting his revenge. They remade it as Payback with Mel Gibson.

(Continued on next page)