The Golden Age of Belgian Comics features a rare collection, on show in France for the first time ever. These hundred storyboards, drawn between 1946 and 1970, belong to the Museum of Fine Arts in Liège, Belgium. Their pages detail a comics revolution, the era when – led by Tintin – the ninth art forever changed leisure on the continent.

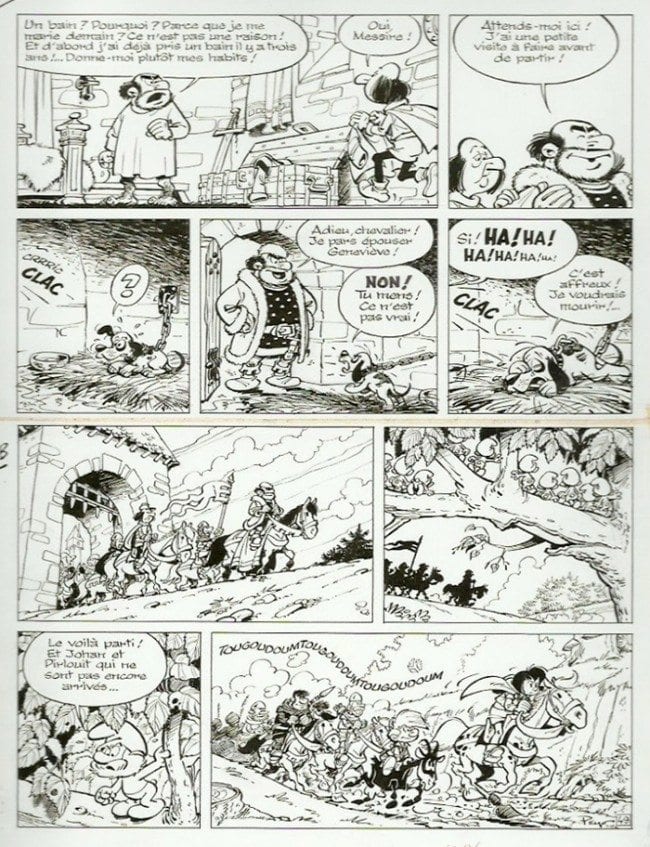

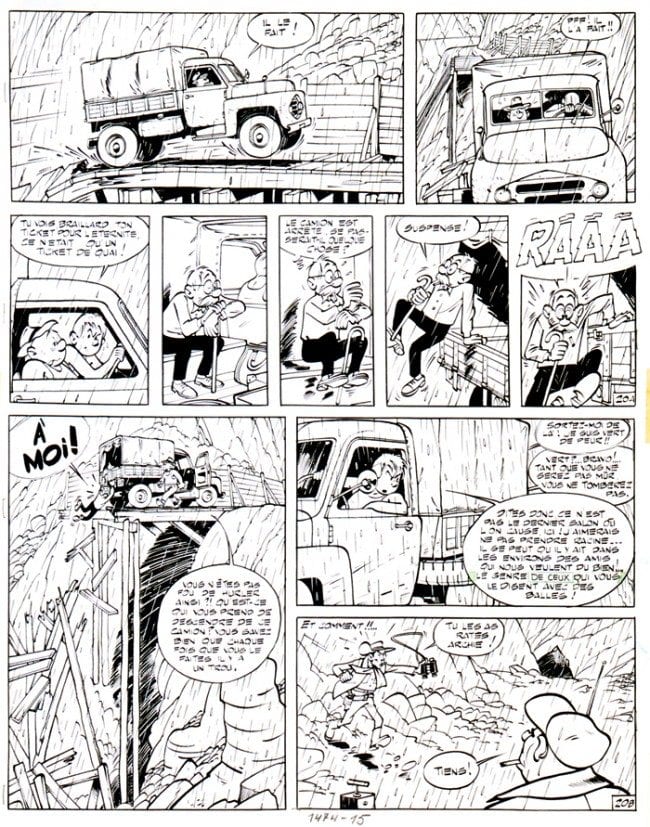

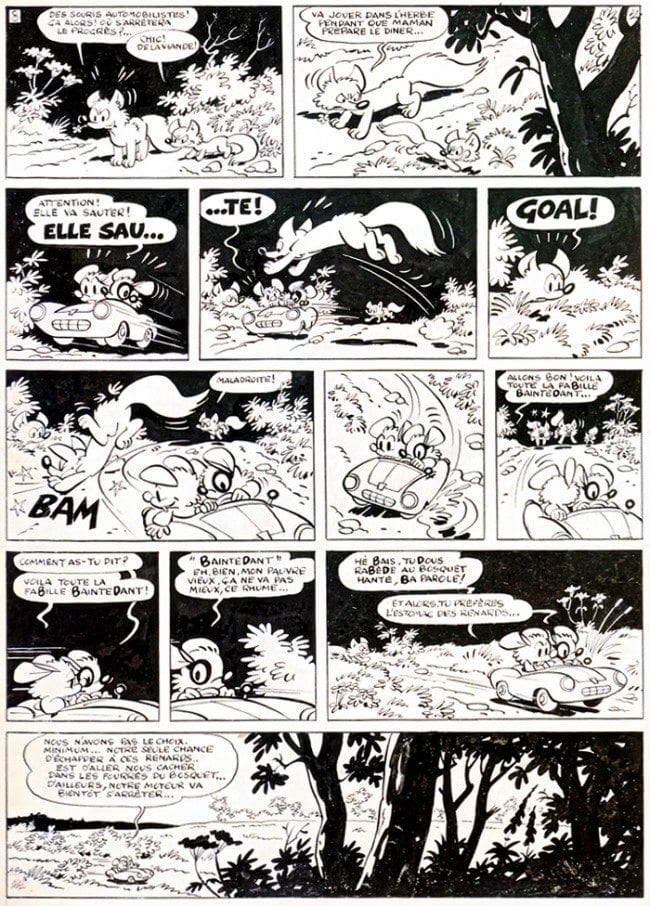

Its big names are the gods of this particular origin myth: Hergé (Tintin); Edgar P. Jacobs (Blake & Mortimer); André Franquin (Gaston Lagaffe and Idées Noires); Peyo (Les Schtroumpfs – the Smurfs); Maurice Tillieux (Gil Jourdan); Morris (Lucky Luke); Raymond Macherot (Chlorophylle and Sibylline); Didier Comès (Silence) and Willy Lambil (Les Tuniques Bleues).

Their tale is as unlikely as it is significant. Few of these artists had dreamed of working in anything like cartooning. Whether it was a life at sea, fine art or detective fiction, their first ambitions were a reaction to the Belgium where they grew up. Society there was mostly sober, parochial and largely Catholic. But then came the World War II, Occupation and Liberation – the first utterly traumatizing, the latter establishing a Euro-dependence on its "liberator."

From films to comics, cars to clothes, all of Europe felt the pull of post-War US style. But, within a decade, these artists managed to fuse it with a European and Francophone experience. Certainly the best of them – Hergé, Franquin, Morris, and Macherot – drew like geniuses. But it was really thanks to insight, intuition and sheer insouciance that they transformed modest genre stories into something all their own. They gave the European comic an architecture much of which remains with it today.

Here, in a remarkable show, is the proof of their capabilities. With two or three exceptions, the works are all black and white and the total effect is stunning. Visitors can scrutinize the subtlest level of blackness, the artists' delicate pencil marks and painstaking touch-ups. The pages still exude both an impressive velocity and the excitement of an art in transition.

The basic story here spirals out of Hergé’s inkwell. When Tintin first appeared, he was dropped into a Europe that worshiped Disney characters and made-in-America strips. Any real development of 'home-grown' heroes was hard, because the 1930s market was flooded with US imports. Then, of course, came the loss and chaos of World War II.

Belgium's "golden age" had began before the War. In 1938, Belgian printing firm Dupuis launched a children’s magazine they named Spirou. Although eventually shuttered under the Nazi occupation, this would reprise publication in 1946 – and go head-to-head with a new Tintin magazine. Numerous Francophone weeklies shared their target audience, offerings such as Vaillant, Le Coq hardi and Le Journal de Mickey. But it was the Spirou-Tintin rivalry that produced a revolution.

Dupuis had given their title story, that of a roguish bellhop, to a French cartoonist named Robert Velter. He was assisted by his wife Blanche Dumoulin and their friend Luc Lafnet. But when 'Rob-Vel' was taken prisoner during the war, the Dupuis passed Spirou on to a local employee. This was Joseph Gillain, better known as "Jijé" (after the French pronunciation of his initials). Between 1940 and 1942, Jijé drew most of the magazine, even its now-embargoed American strips.

After the War, Gillain also reassembled Spirou. Those contributors he recruited were only in their twenties, but three had worked together in animation. That trio were André Franquin, Eddy Paape and Maurice de Bevere (Morris), joined by Jijé's 19 year-old lodger, Willy Maltaite (Will). A second wave of hires included Maurice Tillieux (already a writer of adventure novels) and another ex-animator, Pierre Culliford (Peyo). Before long, each of them would attract his own disciples.

The Golden Age show provides a close look at their talents. Studying the work of only one – Maurice Tillieux, say – shows immediately that Spirou was hardly kids' stuff. Tillieux's 'Gil Jourdan' is a boy detective (a swipe, of course, at Tintin). Yet his creator proved a master of the cinematic, one whose strips ricochet with repartee and fast-paced chases. The comics scenarist José-Louis Bocquet claims that one of Tillieux's inventions was the comédie policière. "He did it in comics years before Michel Audiard put the genre onscreen."

The team's cartooning technique – partly inherited but soon individualised – was an animated, breezy, ultra-modern one. Eventually, it became known as 'le style atome'. This moniker derived from the 1958 Brussels World's Fair, whose signature was a sculpture called 'the Atomium'. An outsized icon of Populuxe design, this seemed to match the sparky visual spirit of post-War Spirou. Certainly it paralleled the artists' angular shapes, their streamlined drawings and a use of bright, sharp colours. Graphically much brasher than Hergé's ligne claire, le style atome gave a nod to '50s and '60s US culture. It featured rounder speech bubbles instead of rectangles and privileged short, spunky dialogue over declamations.

As British BD expert Matthew Screech observes, these component elements depict hope and recovery. "In 'style atome' cities, elegant buildings of steel and glass filled with shiny, ultra-modern gadgets, suggested financial security and material comfort… Style atome glorified the mass-consumerism and technological optimism of a Europe emerging from post-War austerity."

Yet with the passage of time, led by the legendary Franquin, Spirou artists undermined the 'progress' these visuals were suggesting. Combining subversive graphics with a narrative subtlety, they moved European storytelling away from America – especially from Cold War definitions of black and white, right and wrong, good and evil. Franquin's own infatuation with American culture had started to fade long before May of '68. But, after that orgy of Francophone consciousness-raising, everything about his work became influentially provocative.

The first inspiration for Spirou's style, however, was Jijé. More collegial than Hergé, Gillain was an informal, easy-going boss. Also, he had been born in 1914. This made him part of the generation between both his younger staffers and the older Hergé. Initially focused on a life in painting and sculpture, Gillain never expected to make his career from comics. But, as an artist, he turned out to be unique – possessing equal talents for realism and caricature. Although a Catholic believer, Jijé was also unbothered by working with a Communist like Spirou editor Jean-Georges Évard.

Spirou's energetic art is now known as "the Marcinelle school" or "the school of Charleroi". Both terms refer to the site of the Dupuis' printing firm. But those artists who worked with Jijé had a different name for it. They called the work gros nez – or "big nose" – comedy.

The flipside of Marcinelle art was found in the pages of Tintin. A vehicle for Hergé's hero, this weekly was the laboratory of a rival "Brussels' school". Just as Marcinelle art reflected Jijé’s temperament, the Tintin employees operated in Hergé's shadow. Their highly polished work was required to resemble his and, in their atelier, an artist wore his suit and tie. He would labour to produce pristine pages, with refined lines underscored by un-shaded colour.

At Tintin, the artists were also far from ordinary. One of their standouts was E. P. Jacobs, who invented the spy/sci-fi series Blake & Mortimer. Before he turned to art, Jacobs had worked in opera – and his work has a sweeping theatricality. There was also Jacques Martin, French rather than Belgian. Martin created 'Alix', a young Gaul whose exploits take place around the Roman Empire. The Alix series was an immediate success and, thanks to its Egyptian sidekick, also an icon of gay consciousness. Martin never denied this interpretation of Alix, saying just that, "During Antiquity, a pair like Alix and Enak would be normal, and I'm certainly not going to change Antiquity...").

Belgium's Flemish youth enjoyed a comics world of their own and Tintin recruited its star, Willy Vandersteen. Although Hergé praised him as "a Brueghel of the bande dessinée", he made Vandersteen re-tool his trademark series Suske en Wiske. Reworked into a paradigm of Hergé's ligne claire, the series was published as 'Bob et Bobette'.

Most remarkable of all was Raymond Macherot, the artist of Tintin spy series Colonel Clifton. Macherot's drawing style is strikingly immaculate and his anthropomorphic animal tales remain one-of-a-kind. He created the first of these, Chlorophylle, at Tintin. But the best (Chaminou et le Khrompire and Sybilline) came after the artist defected to work at Spirou. Macherot's creatures existed right alongside Disney's but what distinguishes them is a deeply sinister side. Often, these "cute" protagonists turn out to be predators – and each one of his species exhibits unlikeable aspects. Macherot prefigured the dubious fauna of South Park.

Like Hergé himself, Macherot struggled with depression. So did André Franquin, Spirou’s most transcendent artist. But what others suffered in silence, Franquin brought upfront in his art – especially with the singular series he called Idées noires (Black Thoughts).

Franquin remains an artist greatly beloved in Europe and regarded by many as the 9th art's finest draughtsman. He became so popular that, over several years, he was working both for Spirou and Tintin. (This anomaly, as comic as anything he could imagine, occurred after a explosive disagreement at Dupuis. But it produced his ebullient gag strip Modeste et Pompon).

In 1949, Jijé decided to move to America. Franquin and Morris, eager to see the States (and hoping to work for Disney) tagged along for the ride. However, long-term visas for the Belgians proved elusive. So, after a drive cross-country, they ended up in Mexico. During the whole adventure, Franquin kept on drawing Spirou. He was determined to change the little bellhop's world – by adding the presence of evil, radically changing its narratives and making additions like his exotic creature, the 'Marsupilami'.

But, in 1957, Franquin invented 'Gaston Lagaffe'. A true incorrigible (his last name means impolitic blunder), Gaston's persona combines slapstick and sophistication. The character self-referentially "works" at Le Journal de Spirou but his entire existence is indolent and anarchistic. Despite good intentions, Gaston's every move goes wrong – yet he remains utterly unconcerned with consequences. From Mad magazine to Scott Adams' Dilbert, no one has ever produced a better satire of office life. As the French journalist Laurent Joffrin once expressed it: "Gaston dynamites every idol of the moment: marketing, management, productivity, profitability…all the conformities."

So, effectively, did Franquin himself. With Gaston, his work became not just anti-authoritarian. It was also eco-militant, anti-war and against the death penalty. For the '60s and '70s, this was the perfect recipe – and it remains almost eerily up-to-date. Gaston Lagaffe has sold more than 36 million albums.

Hergé's life was dedicated to further refining his technique. But Franquin took an opposite path, creating work that exhibits greater and greater complexity. The culmination of this is his Idées noires. A lengthy set of strips, deeply black in humour, these Black Thoughts portray a world totally lacking in hope. Their elegant graphics, however, are spookily deft and resemble nothing so much as Goya's Caprichos. Adroitly deploying (if not wholly controlling) his genius, Franquin made himself into the anti-Hergé.

One Gaston board in the show previews all of this. As the modern Belgian cartoonist Bernard Hislaire describes it, "Inside the frames, everything is concrete, everything is charged with the energy of the line. The speech bubbles, the paper lying around on the floor, the exclamation points…nothing can be inanimate; everything has to come alive. Fantasio's anger is more than simply buggy eyes, dishevelled hair and a wide, gaping mouth. It's also puffs of cloud around him, lines that tremble like forceful cries and the tail of a speech balloon turned into a zigzag of lightning. There are so many graphic incarnations of the intangible, of invisible and interior moods… it makes metaphysical anguish absolutely palpable."

This is a great show, a well-curated summary of a decisive era. It benefits immensely from a clever scenography, which surrounds its originals with ephemera and giant wall art. But there is a complication to using the term "golden age". The renaissance in question happened before Belgium's colonial project in Africa ended. Ever since 1885, life in the country had been replete with propaganda about her "possessions". Predictably, the results of these stereotypes lived on in comics – even when circumstances required (or artists endeavoured to take) a more progressive approach.

The old iconography of Belgian imperialism juxtaposed childlike natives with hero missionaries, pitting Catholic civilisation against pygmies, cannibals and African "superstitions". Before the War, images like these were rife in popular culture, with comics' most notorious version being 1930's Tintin au Congo belge.

But the post-War Francophone reader still received its vestiges. They can be seen in series like Jijé's Blondin et Cirage ("Blondie and Shoe-Black"), Tif et Tondu au Congo and Franquin's Spirou chez les Pygmées. The show does not feature excerpts from any of these. But certainly several artists here continued depicting black 'Africans' with colonial stereotypes. Spirou may have changed the storylines; Cirage, for instance, is often more resourceful than Blondin. But his large, bulging eyes, red lips and prominent ears derive from something more than humorous imperatives. In addition, the Africans who appeared in Spirou's pages often spoke 'le petit nègre', that pidgin French which was a code for racial inferiority.

As Belgian academic Pascal Lefèvre stresses, this slice of cartooning history is far from a simple one. As well making sensible pleas for a comic-by-comic reading, Lefèvre has noted that, "From the 1960s on, readers of the magazine Spirou saw more Africans in official positions, such as police officers, whereas white colonial employees and traders became very rare…[and] while the more caricatural styles continued to be popular, realistic styles became quantitatively dominant."

If not entirely golden, however, the age remains a momentous one. There's more proof in the show's final room – a small cinema. Here, visitors are invited to watch a set of interviews. The clips feature contemporary Belgian bédéistes, who analyse the standout achievements of their predecessors. Each artist has something to cite which affected his work. There are the fresh angles Macherot found to advance a narrative ("He plays with everything, yet he knows how to place it all. He understands exactly where and how the eye will move.") There is the way Morris balanced homage with parody ("Lucky Luke was Pop Art before the term was ever coined"). Then, of course, there is Franquin's incredible energy ("With him, psychology is always centre stage. Nothing is outside it; even a garbage can must participate").

The superstar François Schuiten sums it up nicely. "Their art had an intimate, organic relationship to its age – and yet it remains totally timeless. The world continued to evolve, cars continued to evolve, psychology kept on evolving. But the hero follows it all."

• L'age d'or de la bande dessinée belge runs through October 4, 2015 at the Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles in Paris