This year is the 50th anniversary of underground comix. The official beginning was the publication in February 1968 of Zap Comix No. 1, which was sold out of a baby carriage on the streets of Haight Ashbury in San Francisco. But the underground was surfacing elsewhere—in Greenwich Village, in Chicago, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and in the unlikeliest of places, Austin, Texas. America culture as a whole was experiencing events as upending and disruptive as anything in revolutionary comic book format, whether ending with an x or not.

The ongoing Vietnam War-inspired protests that spread beyond the campuses where they started into politics and the wider society. As Jackson Lears outlined in The New York Review of Books (September 27), 1968 was the year of “the tormented Lyndon Johnson, enmeshed in an unpopular, unwinnable war and choosing to withdraw from the presidential stage; the anti-war candidacies of Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy; the intensifying moral challenges posed by Martin Luther King, the assassinations of King and Kennedy; the racially charged violence in most major cities; the police riot against antiwar protesters (and anyone else who got in their way) at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago; the emergence of right-wing candidates— George Wallace, Richard Nixon—appealing to a ‘silent majority’ whose silence was somehow construed as civic virtue. ...”

The radical protests featured unknown entities who soon became famous—Tom Hayden, Mark Rudd, Abbie Hoffman, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Panthers, the Maoists, the Yippies, the devotees of Che.

In the midst of this surging social disruption, underground comix were a logical development—however illogical (even demented) and anti-social their content seemed. And they were cropping up everywhere in and around 1968.

The late undergrounder Jay Lynch believed that the term “underground” came via Time magazine from Andy Warhol, known for his “underground” movies; Time applied the term to underground newspapers and, hence, to the irreverent comic books that grew out of the papers.

Comix most profoundly did something mainstream comic books carefully did not do: comix offered cartoonists the chance for self-expression. They drew for themselves not for the company dollar.

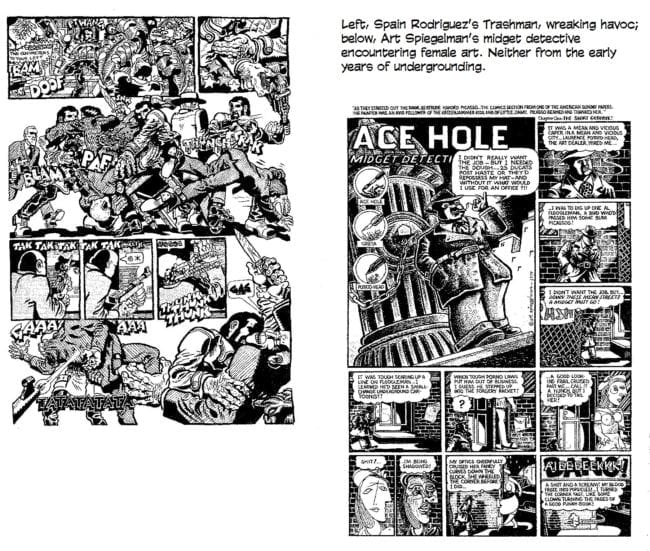

In Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, Patrick Rosenkranz explains that “catharsis was often a motivation for comix. Flaunting fears, shedding demons, confession, confrontation and revenge were often behind the creativity. Spain Rodriguez said that underground comix allowed him to exact his revenge on the Comic Code Authority which killed of his favorite EC Comics in 1954.”

Comix suited the period of their birth and blooming: in an age of anti-war protestation and drug use, comix were vehicles of indulgence and protest, chiefly against the mores of conventional American middle class life.

In the book’s longest essay, “The Undergrounds”, Paul Buhle peels the onion, a layer at a time, to show interrelationships and, also, completely independent sproutings, thereby coming close to tracing the transformation of comics to comix.

Skimming the surface of his essay to scoop up the nutshells, we learn that the origin of comix can be discerned in college humor magazines, which inspired Harvey Kurtzman in founding Mad. Mad, in turn, manifesting the superior artwork of EC Comics as well as a manic satirical humor, fueled many underground cartoonists.

College humor magazines, which were produced without any restraints until they offended ruling faculties, set the pace.

The earliest manifestation of the irreverent sensibility of comix found its outlet in underground tabloid newspapers, most of which had a comics section. The tabloid counterculture was nurtured in the East Village, San Francisco, and Austin, Texas, not along Madison Avenue in New York, where, until comix, most publishing was done. Papers like the East Village Other, Los Angeles Free Press, Gothic Blimp Works, Yarrowstalks, and a few fugitive others fostered the form and the attitude.

And from these, comix emerged in “a frantic combination of talent, energy, dope and almost hand-to-hand distribution.

“The marvel of it all,” says Buhle, “is that suddenly, almost anything seemed possible. From the beginning, a requisite dose of sex would be sure to add to sales. Most artists, male and female alike, had long wanted to work with a sexual content hitherto forbidden. ...

“Underground comix deftly united the most vernacular of all arts, the comic book, with political rebellion and a reflective critique of American culture.”

The counterculture’s preoccupation with the Vietnam War, the draft, racism, environmental devastation, corporate greed and the heartless capitalistic “anything for a profit” system—all influenced a spirit of rebellion that embraced comix, which brimmed with anti-establishment protest in support of the Chicago Eight and “other prisoners of the mainstream culure.”

Enabled by the advance of printing technology that gave small publishers—and individual cartoonists—the means to publish short-run comic books and still turn a small profit, comix had their heyday from 1968 until the mid-1970s. Protypes started earlier in the 1960s, and vestiges lasted long after the 1970s, the most notable being the so-called “alternative” press, which carried the publishing legacy of comix forward.

IN THE MID-SIXTIES IN NEW YORK’S GREENWICH VILLAGE, Spain Rodriguez and Kim Deitch and Art Spiegelman were coalescing, mostly around the East Village Other.

According to St. Wikipedia, the East Village Other was co-founded October 1965 by Walter Bowart, Ishmael Reed (who named the newspaper), Allen Katzman, Dan Rattiner, Sherry Needham, and John Wilcock. It began as a monthly and then went biweekly. The EVO, as it was dubbed, was among the first countercultural newspapers to emerge, following the Los Angeles Free Press, which had begun publishing a few months earlier.

The EVO was described by the New York Times as "a New York newspaper so countercultural that it made the Village Voice look like a church circular." The Voice, which had been founded ten years earlier by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock and Norman Mailer, is usually recognized as the country’s first alternative newsweekly. Although it hosted a variety of writers and artists and cartoonists (most notably in the latter category, Jules Feiffer), the Voice was not known as a newspaper for cartoonists. The EVO, on the other hand, was.

It was a breeding ground for the underground comix, providing an outlet for artists including Spiegelman, Deitch, Rodriguez, Trina Robbins, and Gilbert Shelton before underground comic books emerged with the publication of the first issue of Zap Comix.

The popularity of comic strips led to the publication of separate comics tabloids, beginning with Zodiac Mindwarp by Spain Rodriguez and continuing with Gothic Blimp Works.

Comix historian Rosenkranz recalled his reaction to EVO (quoted in Wikipedia):

“I'd never seen a publication like this before. It was full of wild accusations and bawdy language and doctored photographs. It had President Johnson’s head in a toilet bowl. It had naked Slum Goddesses, truly bizarre personal ads, and a whole different slant on the anti-war movement than my hometown paper upstate. But best of all, it had the most outrageous comic strips.

“The continuing saga of Captain High; the psychedelic adventures of Sunshine Girl and Zoroaster the Mad Mouse; Trashman offing the pigs and scoring babes left and right. While I enjoyed many aspects of EVO, I liked the comics the most.

“Bill Beckman was one of the first cartoonists with his counterculture crusader Captain High, whose main mission was to get high and stay high. Beckman didn't draw very well, but EVO's readership could relate to the premise. Beckman contacted his buddy Gilbert Shelton from back at the University of Texas at Austin, who mailed in an occasional strip called Clang Honk Tweet!; Hurricane Nancy Kalish contributed a spacey, Aubrey Beardsley-style comic called Gentle's Tripout. Others came and went without much notice until Bowart commissioned Rodriguez to draw a 24-page all-comic tabloid, which he published as Zodiac Mindwarp in 1966.”

In 1968, Rodriguez had covered the Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a reporter for EVO. Deitch had been contributing to the EVO since 1967. He was involved romantically with Robbins, who, in 1966, had arrived in the East Village and set up her dress-making boutique (she made only dresses of her size). She made a deal with EVO staffers: she’d sew for them in return for free advertising, and she produced a comic strip, Broccolistrip, as the ad for her shop, Broccoli.

But the cartoonist whose Village associations stretched back the furthest was Spiegelman, who had been peddling self-published underground comix on street corners since 1966.

Spiegelman started drawing comics in 1960 when he was 12. In 1961 while in junior high school, Spiegelman produced a Mad-inspired fanzine, Blase. He attended the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan and met Woody Gelman, who encouraged him to apply for a job at his Topps Chewing Gum Company after finishing high school. But after graduating in 1965, Spiegelman enrolled at Binghamton University’s Harpur College to study art and philosophy. He also did freelance work for Topps, for which he’d work steadily for the next two decades. At Harpur, Spiegelman started a campus humor magazine named Mother. In 1966, he was working for Topps as a creative consultant making trading cards and related products (Wacky Packages, Garbage Pail Kids). And selling those self-published undergrounds on street corners.

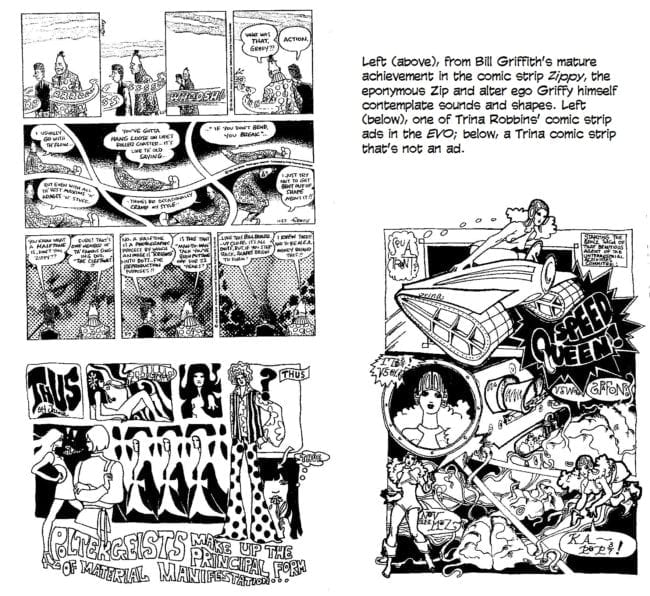

In 1968, Bill Griffith got his start in undergrounding. Griffith grew up in Levittown, New York, the post-World War II housing development that gave housing developments a bad name. All the houses looked exactly alike—a monotonous, sterile environment.

“Mad was a life raft in a place like Levittown, where all around you were the things that Mad was skewering and making fun of,” Griffith told me.

But Griffith first pursued the artist’s muse, not the cartoonist’s. After graduating from high school in 1962, he went to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and studied painting and graphic arts, leaving between his sophomore and junior years to spend a year in Pris, where he lived in a garret (“the top floor of a cheap hotel—I even had a skylight”). When he returned to Brooklyn in 1965, he freelanced at whatever art jobs he could find.

He moved to the Lower East Side of Manhattan in about 1967. There he saw his first underground comics in the EVO.

“I had repressed the comedian and the cartoonist in me for too long,” Griffith recalled. “Seeing the comics in the EVO burst the bubble. I just did a comic strip one day [late in the pivotal year 1968] and took it down to Screw.”

Screw was a freshly founded weekly pornographic tabloid newspaper offering “Jerk-Off Entertainment for Men,” as it proclaimed on its cover. Founded by Al Goldstein and Jim Buckley, it was first published in November 1968.

Griffith continued: “The times being what they were, completely free-wheeling, it was relatively easy to get published. My message seemed to be sufficiently anti-establishment, anarchic—and, most important, the right size. I took it in to Steve Heller (who became the art director at the New York Times), and he pulled out a ruler and measured it. ‘Hey,’ he said, ‘it’s the right proportions. We’ll use it!’

“I was one of the few contributing cartoonists who had bothered to measure what a half-page tabloid size was,” Griffith continued, “and I’d drawn it the right size. I don’t think they even read my first five or ten strips. They were just so thrilled that they were drawn to the correct proportions.”

I chimed in: “So now all aspiring cartoonists reading this will seize upon the right proportions as the direct route to—”

“—To fame and fortune,” Griffith finished with a laugh. “Just measure correctly. The ruler is the pathway to stardom.”

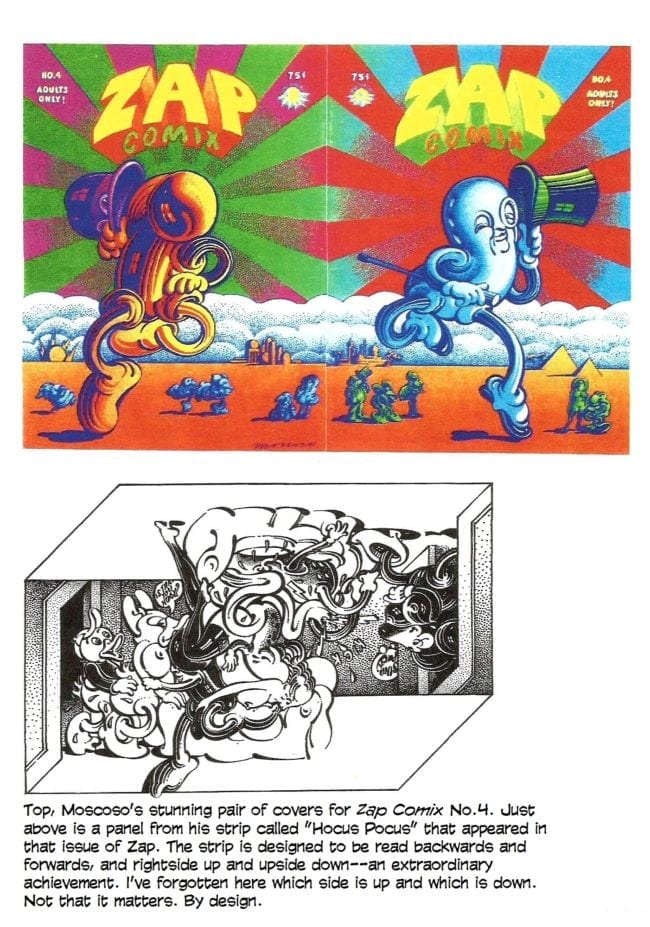

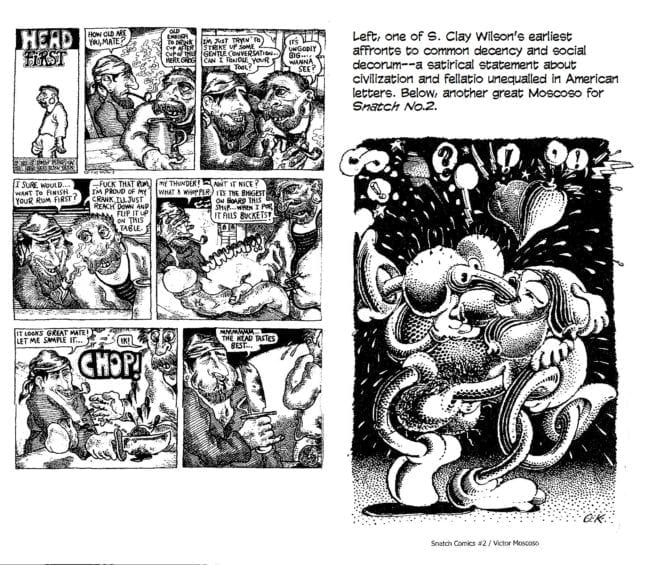

MEANWHILE, IN SAN FRANCISCO, Zap Comix was expanding. With No.2, published in June 1968, it included contributions from two poster artists, Victor Moscoso and Rick Griffin, and a particularly irreverent cartoonist, S. Clay Wilson.

A couple of the earliest Zap stories are satirical in an almost traditional way— R. Crumb's "City of the Future", which ridicules blissful futuristic visions; and "Whiteman", which lays bare the repressed middle-class male. But stories like "Meatball" (about an inexplicable rain of meatballs, that like hits of acid, transform everyone struck by one) and "Hamburger Hi Jinx" (in Zap No. 2), play with subjects in ways that are most amusing, probably, to tripping readers.

The early stories were fun-loving rather than fierce satire; that changed with the debut of Wilson.

A heavy drinker (wine and beer), Wilson had drifted into the Haight one day from Nebraska. An art school graduate, Wilson saw himself as an art outlaw whose function was to use his art to puncture the "booshwah" balloon, to strip "the mass delusion" from the eyes of the American middle class.

"A seething, visionary kinda guy,” said one who met him about then.

Wilson's contribution to the second issue of Zap Comix was violently different from the good-natured big-foot material. Wilson drew stories about bikers and pirates and lesbians and all kinds of unsavory demonic freaks. And he drew them as grotesque gargoyles, ugly and malformed and repulsive— covered with blemishes and scars, warts and unruly hair. His graphic style was raw and uncompromising, and his characters were relentlessly brutish, violent savages who stabbed and chewed each other to bits whenever they weren't committing bizarre sex acts.

Wilson held nothing back, made no concession to social convention whatsoever; he relished offending every civilized sensibility.

The late comics historian Clay Geerdes argued that Zap’s importance at this juncture in the history of comics does not derive from the comix therein: it originates, rather, in the publication of underground comics in magazine (comic book) form.

"It was the book that turned on all those light bulbs and taught people they did not have to submit to the East Coast comic book monopoly and wait for acceptance or rejection. Zap taught them they could do their own."

The first issues of Zap were undeniably a persuasive demonstration that artistic freedom could be achieved through entrepreneurial enterprise. But the book’s obvious zest in playing with the medium and its ebullient selection of unconventional subjects to rejoice with were, in my view, just as precedent-striking as the happenstance of being in comic book format.

But Zap was arguably not the first underground comic book. Many (myself included) believe that distinction belongs to Frank Stack with an able assist from Gilbert Shelton (who had joined the Zap troupe with No. 3).

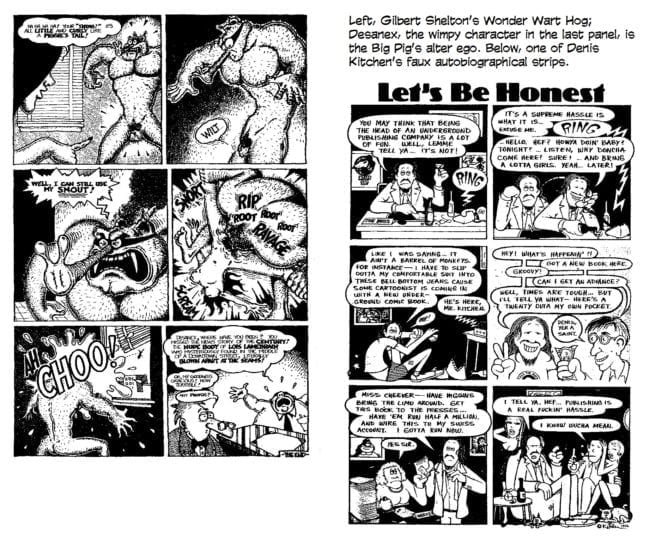

While an art student at the University of Texas in Austin, Stack was editor of the campus humor magazine, the Texas Ranger, in 1958-59, and he met Shelton and published his cartoons. The two aspiring cartoonists became friends, and Shelton eventually became editor of the magazine and published in the December 1961 an installment of his Wonder Wart-Hog— "the Hog of Steel"— a screamingly funny send-up of Superman and the traditions of the long underwear legions.

According to Stack, Shelton had been producing stories about the "Big Pig" since high school. And he recruited everybody he knew to help him write the stories.

"I spent hours with him,” Stack told me, “talking about drawing and jokes in Wonder Wart-Hog as did Lynn Ashby and Bill Helmer in the fall of 1961— probably others did, too, including nonsense poet Lieuen Atkins with whom Shelton collaborated often. He gave credit to Bill Killeen, but I'd say he was just being generous. He was the sole owner and proprietor of Wonder Wart-Hog, script and character and concept. He was, perhaps, despite what some people said of him, very modest about his talent and generous in acknowledging help he got from his friends.”

Stack told me that he wanted Shelton to call Wonder Wart-Hog "the Pig of Iron," but Shelton didn't go for it.

(Killeen later went to Gainesville, Florida, where he started an off-campus humor magazine, Charlatan, to which Shelton contributed more of the Hog of Steel.)

In a letter to me (dated January 15, 1995), Stack added something else about Shelton: “Gilbert was an active participant in the Austin music scene, jammed on the banjo at Threadgills, wrote country blues songs, and recorded the memorable ‘Set Your Chickens Free!' He was also an amateur athlete and semi-professional stock car racer. Modest on one level, supremely cocky and confident-seeming to others— he was extraordinarily good looking and charismatic. Several beautiful women in Austin and San Francisco were in love with him. He was an amusing and attractive guy— genuinely brilliant, too— still is, though ravages show in his countenance now (well, wouldn't they, twenty-five years later?)."

IN THE SPRING OF 1962, Shelton made one of his periodic trips to New York to storm the bastions of professional cartooning. He was mostly unsuccessful, but he spent some time there with Stack, who was then finishing a stint in the Army. They both went back to Austin that summer, Stack en route to graduate study in art at the University of Wyoming in Laramie in the fall.

About that time, Shelton, who was perpetually launching one underground project after another, started a renegade broadside, The Austin Iconoclastic Newsletter (which was called "The" for short), and from Wyoming, Stack occasionally supplied him with some cartoons and single-page comic strips about Jesus Christ in which the Savior is viewed, somewhat (no, entirely) irreverently, from the twentieth century perspective of a person who has read the New Testament with an appreciation for the human predicament rather than an appetite for the divine message.

(When Jesus stops a group of men who are stoning a woman and admonishes them, saying, "He who is without sin should cast the first stone," one of the stoning party, grasping the situation instantly, hands a stone to Jesus and says, "Gosh! Sorry we started without you, Jesus. We didn't know you went in for stuff like this. Here— bop her a good one.")

Raised in the Methodist persuasion, Stack was a regular church-goer until he went to college, whereupon he lapsed and never came back. “The basic idea of [the Jesus cartoons],” Stack writes, “came from a chapter in The Brothers Karamazov called ‘Dimitri’s Dream’ or ‘The Grand Inquisitor’ in which Christ returns [to earth], only to be arrested and imprisoned.”

Smitten by this notion, Stack imagined Jesus coming back and being ostracized by conventional society because, with his long hair, beard and robe, he looked like a hippy.

Shelton, vastly amused by Stack’s sacrilegious productions, decided to disseminate a collection of them. He took eight of Stack's single-page strips to a friend who had access to a photocopying machine and together they ran off about fifty copies of each page. Shelton supplied the cover, a thumbnail-size drawing of the head of Jesus, with the title, The Adventures of J, and the byline, "By F.S.," and stapled all the pieces together, creating the first booklet of comix.

In a telephone conversation with me on January 3, 1995, Stack elaborated on the origins of The Adventures of J. The little eight-page (plus cover) opus was produced, he thought, either in the late summer or fall of 1962, probably after the collapse of Shelton's The newsletter (but maybe not).

Stack remembered that it was Bill Helmer, then an editor with True West magazine, who photocopied the first issue of the little booklet. But when I talked to Helmer a week or so later, he said he wasn't in Austin at the time. A former editor of the Texas Ranger (he followed Stack), Helmer was in New York while Stack was there and returned to Austin in 1963.

He lived near Shelton, and Shelton gave him some copies of The Adventures of J, which, Helmer believes, had been sitting around in a desk drawer somewhere, uncirculated; the pages Helmer received weren't even stapled together. Helmer took them to his office and ran off a few copies, earning a look of askance from his boss, Joe Small, who was a fairly religious fellow.

If Helmer’s memory is accurate, The Adventures of J arrived in 1963, not 1962. But even at the later date, it qualifies as the first comix.

Geerdes quite rightly points out that these early productions have been termed underground comix in retrospect: "The concept [of underground comix] was unknown in 1962; it became popularized in the mid-1960s through the proliferation of underground newspapers."

A fellow underground cartoonist, Jack Jackson (Jaxon), had just arrived in Austin in 1962 with an accounting degree and was working in the state capitol and hanging out with Shelton and others who had produced the Texas Ranger.

"It was rather like a little oasis for us, this wonderful little thing called The Adventures of J," he said. "For somebody like me, who had all these religious hangups that I still hadn't shaken, this was just a breath of fresh air. It poked fun at the Scriptures and the sanctity and Godhead of Jesus and all that, and rather made him like a normal guy. Frank Stack, bless his heart, is finally getting some belated recognition on that."

TWO YEARS LATER, in 1964, Jaxon published his own "breath of fresh air"— God Nose (Snot Real), a prototypical comix about the hilarious dilemmas of a bearded, bulbous-nosed dwarf-sized god trying to fit into the twentieth century. Jaxon sheds light on the matter as he explains the origin of the book and its title:

"We were doing a lot of peyote in those days, quite legal at the time, and among other things, it makes your nose drip. So under the influence of this stuff, sitting around with some of these loony guys, we came up with a character called ‘God Nose.’ It was strictly drug-induced. ... Anyway, God Nose was an attempt to render some of the ridiculous absurdities that had come through from these peyote sessions."

In recalling the early days of comix, Jaxon said: “Comix were for aficionados and dopers and whatnot from the beginning. We were just entertaining our friends, so to speak."

In short, these comix were likely to be funny only to those readers who were stoned at the time.

A couple years later, all the Texas alums were in San Francisco.

By 1966 or so, the campus humor magazine scene "fell apart," according to Jaxon. “People did things that alienated the school censors".

Shelton and Jaxon had heard about the poster business in the Haight; Chet Helms of the Family Dog was an expatriate Texan ("one of the old peyote party"), and Jaxon went to San Francisco to make posters for Helms. Shelton made the trip in 1968— also intending to cash in on the poster trade— and about the same time, so did two other Texans, Dave Moriarty and Fred Todd. The four of them pooled their resources and bought an old Davidson printing press, moved it into Don Donahue's loft upstairs at Mowrey's Opera House, and began providing an alternative to the Print Mint for both comix publishing and poster production.

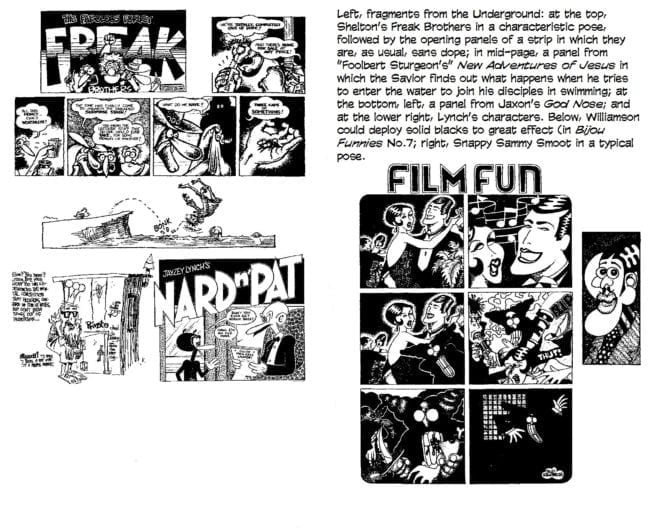

In January 1969, they started calling themselves Rip Off Press, and their first publication under that name was a collection of Stack's cartoons and strips about Jesus. Called The New Adventures of Jesus, this was in regular magazine format, and it identified "F.S." as "Foolbert Sturgeon." The name, Stack told me, although inspired by his initials, was intended to sound like Gilbert Shelton, "deliberately to confuse."

By this time, Shelton had gone beyond college humor as a cartoonist. In 1967 while still in Texas, he had created a 16mm movie called "Texas Hippies March on the Capital." To promote the film, he drew a comic strip about three potheads desperate to score some grass. The trio— Phineas, Freewheelin' Franklin, and Fat Freddie— were better received than the movie, so Shelton gave up his film career and began cartooning the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Shelton's strips appeared in the L.A. Free Press and in various underground outlets, but their splashiest debut was in Shelton's first comix book, Feds `n' Heads, published in 1968.

Harvey Kurtzman reportedly thought Shelton the most professional of the underground cartoonists. And certainly if professionalism means consistent quality and long-range commercial reliability, Shelton qualified.

In the Freak Brothers, he created idiotic icons for the youth drug culture: sex-starved and dope-hungry, they are perpetually seeking a girl or a stash and are almost always frustrated, ludicrously, in the attempt. Shelton's work fits the classic mold for comic strip comedy. And he deployed the medium with a sure hand; his stories always conclude with a comic punch.

Comix by Shelton do not leave the reader befuddled by philosophical conundrums or enraged by social injustice: they make the reader laugh. (Well, sometimes a bit of philosophy creeps in— like Freewheelin' Franklin's immortal axiom, uttered in the very first post-promotional appearance of the trio: "Dope will carry you through times of no money better than money will carry you through times of no dope.")

Rip Off Press published the first collection of Freak Brothers strips in 1971. Since then, dozens of Freak Brothers books have appeared. By 1984, over two million comix, books, and posters about them had been sold worldwide, and their adventures have been published extensively in foreign translations. (See “Rip Off Press” in The Comics Journal 92, August 1984.) Their popularity easily outlasted the counterculture that spawned them.

The secret of their appeal to the youth of subsequent decades is doubtless a certain timelessness: as potheads perpetually in pursuit of an illegal substance, they are in active rebellion against the rules of their society just as most young people are in rebellion against the custom of their elders.

Says Shelton (with a perfect awareness of exactly what he is doing): "They're traditional literary characters just doing the same things that people have always done in more or less contemporary garb."

THE HAIGHT, THE VILLAGE, AND AUSTIN were not the only venues for comix in those formative years. In Chicago, Jay Lynch, another thorough-going professional humorist and cartoonist, was also nurturing the infant medium. Like virtually all underground cartoonists, he spent his fledgling years on college humor magazines. While studying at the Art Institute of Chicago, Lynch contributed to Aardvark, "The Kicked-Off Campus Humor Magazine," for Roosevelt University. He also sent cartoons to Killeen's Charlatan in Florida. Between 1962 and 1966 (while a student in college), he wrote for Cracked and Sick, the Mad imitations.

Lynch was in touch with almost all of the cartoonists whose work would shape comix. Through a letter he read in Cracked in 1961 when he was about 16, he met (by exchange of letters) Art Spiegelman in New York and Skip Williamson, growing up in Canton, Missouri. And when he visited Killeen in 1963, he saw Shelton's Wonder Wart-Hog and was soon corresponding with Shelton and Jaxon. Lynch would make trips to New York to hang out with Spiegelman. He journeyed to Missouri to see Williamson.

Visiting and corresponding with many of the ug cartoonists, telling everyone what everyone else was doing, Lynch was a veritable linchpin of underground comix

In 1967, Williamson moved to Chicago with the object of joining Lynch in producing a humor magazine. They launched the Chicago Mirror, "a kind of magazine somewhere between the Realist and Mad," Williamson said. Lynch elaborated: "It was a satire magazine for hippies— which was a contradiction in terms since the hippies en masse seemed, by this time, to totally lack a sense of humor. By 1967, hippiedom had become a national fad and converts to it were predictably humorless."

Lynch saw a copy of Zap Comix No.1 and changed direction. He and Williamson preferred cartooning to the comic journalism of the Chicago Mirror, so they abandoned their first-born and conceived Bijou Funnies, destined to become one of the longest-running early anthology titles in the underground. For it, Lynch produced stories about Nard and Pat, an Andy Gump-ish bachelor and his ne'er-do-well pet cat (whom Lynch had invented earlier while contributing to the Chicago Seed), drawing in a meticulously clean and uncluttered manner and modulating the stark black and white pictures with a range of grays in Zip-A-Tone.

Williamson's graphic style is similarly unencumbered, but his work has an entirely different appearance: affecting an Art Deco flatness and adding texture with a variety of hatching and patterning, Williamson created Snappy Sammy Smoot, a counterculture Candide who, despite repeated defeats, never loses his innocence.

Meanwhile, in Wisconsin, another campus humor magazine was about to give birth to a comix magazine. In Milwaukee, Denis Kitchen was fermenting his own home brew of comix in the fall of 1968. He'd been co-founder, art editor and the chief cartoonist for the first issue of Snide, a humor magazine for the University of Wisconsin. And when the editor scarpered with the first issue's profits, Kitchen was left with a pile of cartoons he'd prepared for the second issue. Not wanting to have his effort come to naught, he decided to do some more comics and publish the lot in his own magazine.

One problem, typical for the time. He’d graduated from UW in June, and he was almost immediately drafted: in November, he was to be inducted into the army, an event that he, like millions of others in those days, wanted to avoid. He knew he’d probably be sent to Vietnam, a war he opposed, so he sought ways to escape this fate, as reported in Kitchen Sink Press: The First 25 Years.

Tall and thin, he desperately tried to lose enough weight to avoid induction. But come November, one pound over the minimum weight for his six-foot-five frame, he was shipped to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he quickly entered a conspiracy with another borderline weight case, an overweight inductee equally desperate to adjust his weight—but to gain pounds, not lose them.

“He ate my mashed potatoes,” Kitchen reported, “and I ate his crackers and water. Twenty-two days later we both got out.”

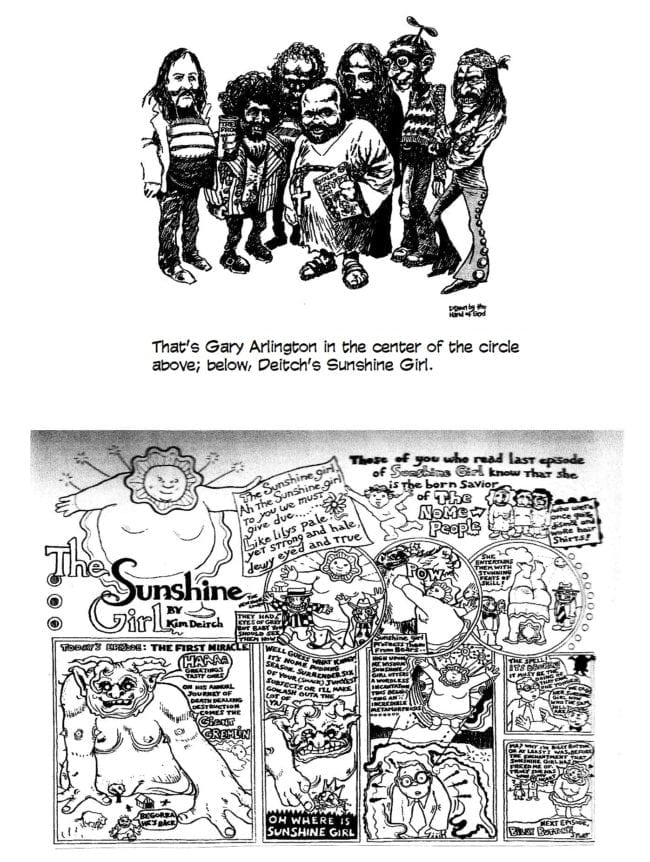

Back in Milwaukee by December, Kitchen was a bohemian denizen of the post-graduate enclave on the fringes of the college campus. He frequented the local head shops and counterculture boutiques and saw copies of Zap Comix and Bijou Funnies in the stores. Inspired by what he saw, he forged ahead on his comix project, publishing Mom's Homemade Comics No.1 ("Straight from the Kitchen to You") in the spring of 1969.

A roommate took copies to San Francisco for sale through Gary Arlington's shop, the San Francisco Comic Book Company on 23rd Street in the Mission District, and made arrangements with the Print Mint for reprinting the first issue (which had successfully sold out) and for printing the forthcoming second issue. But with the second issue, a dispute over revenue ensued, and Kitchen decided he would be happier publishing his own comix, so he severed relations with the Print Mint and began preparing material for the third issue of Mom’s.

Kitchen had sent copies of his comix to Lynch and other worthies. And later in 1969, Lynch took a trip to Milwaukee to meet Kitchen. Lynch’s Bijou Funnies was being published by the Print Mint, and when Lynch found out later that Kitchen was jumping the Print Mint ship to publish himself, he asked Kitchen if he would publish Bijou Funnies too.

"Sure," Kitchen said, "two's as easy as one." A fateful comment. And naive, as Kitchen was soon to discover (and always to admit).

But it was the cornerstone of a publishing empire: Kitchen Sink Press prospered and established new standards of quality in product and of equity in the treatment and payment of cartoonists.

DESPITE ALL THE INNOVATIVE ENTERPRISE in Austin and in the country's heartland, San Francisco was still the hub of the comix movement. Bill Griffith (whose underground character, Zippy, was eventually—astonishingly— syndicated by King Features in 1986) started in the Village but moved to San Francisco immediately after his first visit there in April 1970. He had been contributing strips about his character Mr. Toad to the EVO and Screw, both published in the East Village, but San Francisco was "a magnet," he said; "there was no resisting its pull."

For an underground cartoonist, it was, by then, about the only place to be. The underground newspaper comic strip in New York had expired by the end of 1970; comic books were the only outlet, and they were published most regularly in San Francisco.

"Within a very short time, almost all the cartoonists had either come out to San Francisco," Griffith told me, "or had stopped doing comics. Everybody came out. I was just part of a wave of people coming out here."

For most cartoonists, cartooning is essentially a solitary occupation, but the ambiance of San Francisco at that time was more like the fabled Mermaid Tavern of Elizabethan England where people got together frequently and talked about what they were doing.

"It was like an art movement," Griffith said. "You joined an art movement; that was the feeling. It was a lot of things. First of all, it was a definite part of the hippie movement, the counterculture. We were part of the whole Haight-Ashbury scene. By 1970, it had started to fade— or change, at least, the tail end of the counterculture— but it was still very much alive in the social sense of everybody feeling connected. There was a kind of party atmosphere to some degree; and then there was the sort of salon atmosphere. We hung around Arlington’s comic book store. If we were a salon, he was Gertrude Stein. In fact, he kind of looks like Gertrude; he looks more like Gertrude Stein every year.

"We would hang out at the comic book store," Griffith continued, "and we would have regular parties at the publishers' offices, Rip Off Press and Last Gasp."

The last of the major underground presses, Last Gasp Eco Funnies was founded in late 1969 by Ron Turner to fight for the preservation of the ecology; its first title, Slow Death Funnies, was published in 1970. The salon atmosphere often crackled with discussions of the causes taken up by the counterculture's crusading spirit.

"There were plenty of factions within underground comix," Griffith said, "just as there were within the prevailing counterculture, so some cartoonists felt a responsibility to promote certain ideas."

AMONG THE FACTIONS was a small group of women cartoonists. Trina Robbins and Kim Deitch left New York and Robbins’ dress-making business in late 1969, joining the lemming-like migration of underground cartoonists to San Francisco. And it wasn’t long before Trina began to feel resentful of her treatment as a woman cartoonist. When encountering new bunches of cartoonists, she was introduced as a dress-maker—if she was introduced at all.

In her autobiography Last Girl Standing, Robbins reports missing out on cartooning assignments because the “inner circle” of misogynist male underground artists ignored her being a cartoonist, as they ignored all women cartoonists.

Ignored because she was female, she become a feminist. Out of justifiable resentment—Trina’s and others’— the women’s movement in comics was doubtless born.

In her essay in Underground Classics, Robbins makes the case that women cartoonists produced comix in protest against male preoccupation with abusive sex. With Barbara “Willy” Mendes, Trina co-edited the first all-women comic book, It Ain’t Me, Babe, in 1970, and was deeply involved in Wimmens Comix, the first all-woman underground comix, the product of a “women’s collective.” (Trina edited only one; for the first issue, she produced the first-ever story about an “out” lesbian, “Sandy Comes Out”).

She traces the growth of comix by women and notes that comix were in part reacting against the repressive Comics Code Authority that had destroyed imaginative works in mainstream comics and in part embracing the hippie dogma to “let it all hang out.”

Undergrounds offered women first opportunity to enter the medium. Said Trina: “We tackled subjects that the guys wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole—subjects like abortion, lesbianism, menstruation, and childhood sexual abuse.”

After a few delirious years of unencumbered comix production in the various hotbeds of protest and revolutionary ridicule, underground comix were suddenly snuffed out. The change that ended undergrounds was the Supreme Court decision in 1973 that declared that local standards could determine obscenity. The chief distribution means of underground comics, head shops, couldn’t risk it anymore: their connection with drugs already made them a threatened species. Without distribution, comix slowly died.

By choosing rebellion and confrontation with the power structure of conventional life, underground comics sowed the seeds of their own destruction. Said Kurtzman: “The underground was doomed to self-destruction. Like the Shakers who didn’t believe in sex, the underground didn’t believe in survival. As Shelton put it: ‘If we succeed, we’ve failed. But if we fail, we’re successful.’

“The underground cartoonists had a suicidal philosophy, and the ones I knew were all very frustrated guys, torn between a desire for material success and a contempt for it.”

But comix had a profound and lasting impact upon the mainstream comic book industry. Very early, comix publishers responded to cartoonists’ need to own their own material. And soon, the mainstream publishers—Dark Horse and Marvel and DC and others—responded. First, by returning the artwork to the artists; second, by sharing profits. These adjustments invariably led to better product: more accomplished writers and artists were attracted to comics and produced work in them.

And comix affected the form itself, too. The autobiographical nature of many of the comix stories led, at least indirectly, to the emergence of the graphic novel. But the graphic novel was also the beneficiary of other aspects of the post-comix world. The improving quality of comics led to increased circulation and sales, which permitted and encouraged longer works—graphic novels.

Would graphic novels have come about without underground comix? Probably—under the influence of European comics, which, with the gradual ascent of comics up the social approval scale, began to have an effect on comic book artists and publishers in this country. But the wild excesses of comix doubtless hastened the development.