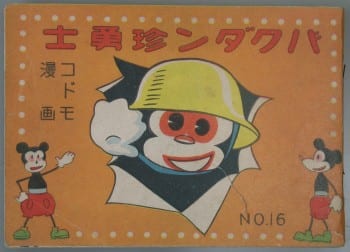

The norm was mediocre. Mickey was usually flat, a geometric abstraction devoid of any plasmatic animation, who toddled around like a stack of blocks. The material is interesting, and I will save it for a different essay on Hollywood in prewar manga, but here is one example that shows just how depraved Mickey could be during Tezuka’s youth. Like the Shitgrin Mask in the postwar period, this manga is not representative of akahon of its era. It is the most poorly drawn children’s manga I have seen from the prewar period, Mickey material or otherwise. No publishing data whatsoever. No publisher name. No author. No date. I have another Mickey manga similar in print quality and color and possibly by the same publisher. It is dated 1934, from a place called Kanei Hakkō in Tokyo. This one could be from the same time and publisher, though the quality of the art suggests a different house and the content maybe a slightly later date.

The Extraordinary Brave Soldiers of the Bomb (Bakudan chinyūshi). Its title is a riff on “Bakudan san yūshi,” “The Three Brave Soldiers of the Bomb” – sometimes translated as “The Three Human Bombs” – a famous military episode during the so-called “January 28 Incident” of 1932 in which Japanese forces attacked Shanghai in response to the destruction of Japanese business holdings in the city by Chinese residents. In a battle on February 22, three Japanese infantrymen stormed through a rain of bullets to ram an explosive charge against the enemy’s barbed wire fences, clearing a path for their regiment but blowing themselves up in the process. Based in fact, the episode was quickly mythologized, covered widely in the Japanese press with 100-plus pt. headlines, and retold in books, a movie, and kabuki, bunraku, and shinpa plays with more than a little embroidering. It was made into a song and sold well on record. It became standard in children’s picture books and school textbooks, standing forth as a lesson in the nobility of soldier bravery and sacrifice. It appears a few times in manga, like this one, where the soldiers are now animals, probably monkeys, their outfits and bodies modeled on Mickey, with different faces and no mouse ears. There are not one but three teams of three that blow themselves up.

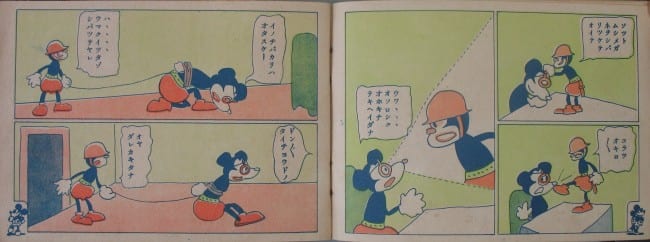

The last of the soldiers is blown out of the battlefield and into the chimney of the enemy’s camp. He finds there the enemy chief sleeping at his desk. It is Mickey. It is not enough to kill or capture the enemy. He puts magnifying glasses on Mickey’s face and kicks him in the snout. “Ooooh. . . how frightening, a giant enemy soldier,” he says upon waking, seeing the little monkey blown up to Kong size. The frightened Mickey is tied up. The rope is fed up through the chimney. The other end is tied to a plane passing by. Mickey is dragged up and out into the sky. The brave monkey is commended for his good work.

This is just one episode in the book. The others are equally cruel and ugly. In another, Mickey after Mickey gets bashed in the head with a club. The last gets his head slammed in a door. Another gets stabbed in the stomach. Another gets speared in the head. Others get bombed from the air. One gets thrown from his plane. One gets a spinning propeller to his face.

In one of his pre-debut works, The Day of Victory (1945), Tezuka casts Mickey similarly in the role of enemy fighter pilot. In that case, he is grouped with other American cartoon and animation characters. That Mickey should belong to an American enemy seems natural given his country of origin. Extraordinary Brave Soldiers, however, was probably made before Pearl Harbor. Therefore, like the pigs in Norakuro, Mickey must logically be Chinese. His thrashing cannot be read simply as symbolic violence against Amerika. More important is that he is foreign and funny. Because he is foreign, he can be cast in practically any role. Shaka likewise recognized Mickey as flexible – his range as a performer – but did not force him into overly alien scenarios. But here he plays the stupid and hapless Chinese soldier. Also exploited is Mickey’s comic status. As hero of the little man, there was a limit to which Mickey at home could be beaten, always coming out on top in the end. Now he makes Japanese laugh as an object of abuse and ridicule. Shaka shows him surrounded by admirers upon arrival in Japan, suggesting he might be accorded the same respect beyond America’s borders. But if that scene were in this akahon, it would have to show instead the mouse promptly stripped of his honor, stripped of his rights, rolled up rudely into the red carpet laid out for him, and thrown into the ring of cartoon cruelty and beaten over and over again with a Japanese slapstick. That Mickey should be drawn so badly here is thus appropriate. Commanding little respect as a character, he demands even less as a design or as a property. Fanfare around the Disney Studio as the vanguard of innovation and quality offered no protection. Popcorn hands and doodle face? Marks of a bad artist, of course. But also signs that Mickey was free to be manhandled.

It’s not that the artist or publisher didn’t know what Mickey should look like. After all, there he is on the bottom corner of every page, made to dance through a flip-book element, recalling his origins in Disney’s animation. The Japanese knew what he looked like and where he came from. They simply did not care. For the publisher and artist at least, laughs were sought precisely in Mickey’s degradation. Akahon regarded him as little more than a funny rodent to be exploited for his popularity.

(Continued)