There is a saying in recovery that one should "tell on your secrets," lest your secrets consume you and lead you into self-destructive behavior. Kevin Budnik's emotionally raw and painful memoir comics find him telling on his secrets, again and again. Unlike a memoirist in the tradition of Crumb, holding nothing back and committed not to censor himself, Budnik's revealed thoughts are not of his basest desires, but rather of his deepest fears and the ongoing, active experience of living with mental illness. His first collection of strips, Our Ever-Improving Living Room, was full of fairly typical journal comics, little anecdotes about daily life that ranged from banal to amusing, even though one could sense Budnik slowly starting to reveal his deeper feelings. His subsequent work, in places like Dust Motes and Flower Grow, was where he started to discuss the reality of his eating disorder, accompanying body dysmorphia, and severe obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Picking up in 2014, Handbook is a journal of both his day-to-day life in that year as well as a look back at the therapy for his eating disorder he underwent two years earlier. The format here is pretty much the same as all of his comics: four panels to a page, each completing a single thought as they create a familiar comic strip rhythm. The book is also full-color, adding life and variety, with a darker, single-wash tone used to indicate flashback scenes.

In terms of its formal qualities, Handbook is Budnik's peak work. The juxtaposition of timelines is part of this, but even his writing has a certain sense of artifice that drops away in his subsequent work. There's a bleak, sardonic sense of humor at work here, which is supported by the four-panel structure. I've compared his work to a cross between Jeffrey Brown and Charles Schulz, with a dash of his former teacher Ivan Brunetti thrown in as well. What's also evident in his work is his internal sense of conflict. That's not limited to just his feelings about his appearance and self-worth; it also extends to his confusion regarding his own desires, which he hints that he finds repulsive at times. There's also the intense push-pull between solitude and getting out of his comfort zone as a way of battling depression, even as his OCD caused a split between him and his former roommate, a longtime friend.

Budnik explores the visceral discomfort he feels with his body, and how he used methods like wearing tight clothing to make himself feel better. The idea was that being skinny meant being lovable, even as his appearance began to startle his friends and family. He goes into detail regarding the charts one fills out while going through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and acknowledges that he's addicted to routine as a way of fending off his OCD. Midway through the book, he begins dating someone, and that falls away. Later, he starts dating someone else long-distance and gets a cat, slowly taking steps out of his solipsistic bubble and realizing that he needs to go back to therapy to address his other issues. There are moments of hope and growth, and while Budnik is still struggling at the end, the point of this book is how hard he had worked and how far he had come. There is a nagging feeling that the end is perhaps just a little too neat, and that plays out a bit in his next book, Epilogue.

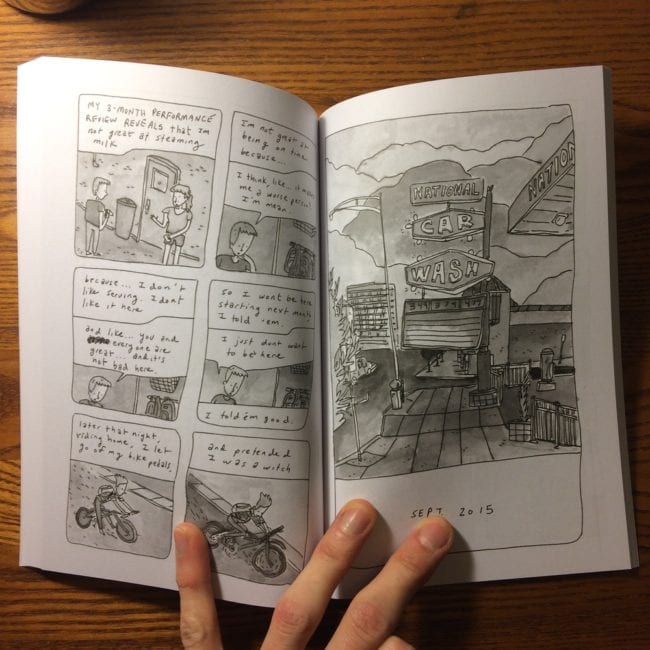

Epilogue is in black and white with a gray wash throughout, but Budnik plays around with his page design much more this time around. This book covers the events of 2015, and one can sense Budnik becoming more insular and even misanthropic, even as he tugs at those tendencies. There's a full-page drawing of a customer he finds obnoxious at his grocery-store job, for example, that's meant to be played for laughs but has an unquestionably nasty tone. The events of the book are chronological, but he doesn't tie things down to specific dates very often. Everything is just fluid here, and the looseness extends to the shaky hand-drawn panels and expressive drawings. Indeed, the high level of control found in Handbook is completely discarded in favor of more scribbly and lively drawings. It feels as if the comics were drawn as each event was happening, giving the book a powerful sense of immediacy.

That immediacy almost feels manic at times, as though his life was spinning out of control. Sure enough, Budnik presents scenes where he's alienating his long-distance girlfriend and expressing resentment toward his job and even his friends. Settling into a 2x3 grid, Budnik creates a different kind of comedic rhythm at times, where each page is set up as though it was going to have a punchline, but Budnik either subverts that or includes something dark. His girlfriend eventually breaks up with him, which leads to him feeling guilty for not including her point of view in this autobio comic. He starts acting out at work and quits. He's stuck between trying to be responsible, caring, and open, and feeling completely withdrawn from adult life. All the while, Budnik is drawing these beautiful scenes of Chicago, observing them but unable to feel joy in that beauty. He nails the push-pull relationship he has with others; he wants to be wanted and loved by his friends, but he also wants to retain the power to say no and be by himself.

He paradoxically doesn't know what kind of art he wants to make, while simultaneously working constantly on his comics. He looks back on his childhood and sees unhealthy patterns that have extended into his adult life, causing him to feel like an impostor as an adult. A lot of his comics are about him cleaning things up, another reflection of his OCD that allows him to feel more in control if his apartment is constantly tidy. Despite having many unhealthy habits, there's still a sense of gratitude as this volume closes out. He's now aware of his tendency to push everyone away and he tries to combat it by attempting to create new memories with others. The end has a clever sequence in which Budnik explores the qualities of long-distance friendship in the simple gesture of picking someone up from an airport, but that has a clever double meaning because he's also thanking the reader in that moment for picking him up, i.e., picking up the book and reading it and in so doing, picking up his mood.

Everything Is Really Hard Today (Tinto Press) is his collection of 2016 strips, and demonstrates how much format can affect storytelling choices. By this point, Budnik had started doing a daily journal comic as part of his Patreon, and this collection crams six of those 2x2-panel strips onto a single page, with an occasional longer interlude that's drawn at a larger size. In some respects, publishing a daily diary harkens back to his earliest work. The difference is that while some of the strips are about quotidian observations and anecdotes (like putting too much garlic in a dish or noticing that a kid on the bus smelled of weed), an equal number of them are about daily struggles. He worries about his body, his overall appearance, his OCD behaviors, his inability to make eye contact with others, and a feeling that he's self-absorbed to such a degree that he can't listen to or truly empathize with the problems of others. That sense of self-awareness and helplessness pervades the book, even as he tries to find ways to work through it. He is, literally, his own worst critic.

The longer pieces in the book tackle tough emotional matters head-on. He talks in detail about his repetitive behaviors, thinking about it from the point of view of what his neighbors might say. He feels bad for his dad that he has to pull the plug on his brain-dead uncle, but is brutally honest in revealing that he has no feelings about his uncle whatsoever. He accidentally breaks a picture when he gets angry about not being invited to go out to a bar and chastises himself for that reaction. Really, the only thing that breaks up the monotony of his daily existence in the book is his traveling to comics shows. These are like palate cleansers, forcing him to abandon habits and reach out to others. He later gets into a long-distance relationship and pulls away yet again. He finally faces up to his depression and gets a new therapist.

This volume is unrelenting in its honesty and in Budnik's need to expand on his fears, feelings, and hopes on every page. This is the ideal version of a cartoonist not censoring themselves on the page, only instead of drawing lurid power fantasies as a way of concealing what really drives him, Budnik is willing to make himself look fragile. He's not just "spilling some ink" (as Rob Kirby and I refer to autobiographical cartoonists digging deep in telling their stories), he's knocked over a whole bottle. That metaphor is especially applicable to Budnik, who compulsively cleans as a way of controlling his environment. He has the option of concealing his feelings and symptoms, yet he chooses not to. I don't get the sense that he's doing this because he's being an emotional exhibitionist. Rather, it seems to go back to that idea of "telling on your secrets" as a way of loosening their power and the sense of shame they bring, even if he gets little immediate relief from this.

There are some ethical concerns with this approach that Budnik acknowledges. In writing about relationships, it means he's going to share emotionally intimate details about someone else in a public context. Indeed, toward the end of this volume, when he takes a chance on that long-distance relationship, one can feel the initial hesitancy give way to joy, which is nice but still reveals personal details about someone else. To be fair, he never tries to make other people look bad or use his strip to get back at someone. Still, he understands the fine line an autobiographical cartoonist must walk.

The art in this volume reveals just how many pages he's drawn and how much he's written. At a certain point, even in the quickest and sloppiest of drawings, one can see his increased mastery over gesture and body language. He's shored up and is comfortable with his figure drawing style. His use of color complements his work subtly, feeling part of a whole rather than something tacked on. Color is an important part of Budnik showing the reader the beauty of the world, revealing that he can relate that experience even if he doesn't always enjoy it. Everything about his work is spontaneous and immediate, as he simply doesn't get precious with his drawings.

Coming to grips with his own mental illness is the focus of much of his work, but One Thing at A Time, Bud (a minicomic published by Birdcage Bottom Books) is about his father getting cancer. It's an excellent family memoir, as he reflects on how much he loved his father. Budnik is an only child and he reveals that his father had an abusive father, and so his dad vowed to not display his temper and to be loving at all times. That's just what he did, and the result was Budnik having incredibly supportive parents who were always there for him. As Budnik freaks out a bit over the initially inconclusive medical events surrounding his dad, he is struck by a sense of not wanting to think about it at all and fearing the worst. He marvels at his father's never-flagging sense of humor and his mantra of "one thing at a time."

The irony is that all of this came at a time when Budnik got into therapy, started taking antidepressants, and was in a loving long-distance relationship. This allows him to stay engaged and present with his dad, even joking around with him on the phone. It's clear that those conversations meant a lot to both Budnik and his father, that laughing was the only thing they could do. As the narrative progresses, there are hopeful signs and then a heart-dropping announcement that his father's cancer had metastasized. Even that word, when he heard it from someone else, made him feel "something skip, it felt hot and fast, like a knife." Budnik then shows a scene where he is talking to his therapist about all this, revealing that his father was his source of strength as a kid, when the weight of mortality really started to hit him and the first hints of depression were emerging. As his therapist says, dealing with the reality of one's parents growing old and dying is part of growing up. By leaning into his feelings and staying close to his father rather than trying to separate himself Budnik reveals just how much he had grown, even as the book ends on a hopeful but unsure note. His father did die in 2017, the ramifications of which are discussed in his daily strip.

The irony is that all of this came at a time when Budnik got into therapy, started taking antidepressants, and was in a loving long-distance relationship. This allows him to stay engaged and present with his dad, even joking around with him on the phone. It's clear that those conversations meant a lot to both Budnik and his father, that laughing was the only thing they could do. As the narrative progresses, there are hopeful signs and then a heart-dropping announcement that his father's cancer had metastasized. Even that word, when he heard it from someone else, made him feel "something skip, it felt hot and fast, like a knife." Budnik then shows a scene where he is talking to his therapist about all this, revealing that his father was his source of strength as a kid, when the weight of mortality really started to hit him and the first hints of depression were emerging. As his therapist says, dealing with the reality of one's parents growing old and dying is part of growing up. By leaning into his feelings and staying close to his father rather than trying to separate himself Budnik reveals just how much he had grown, even as the book ends on a hopeful but unsure note. His father did die in 2017, the ramifications of which are discussed in his daily strip.

Those strips are collected in a mini-series called It's OK to Be Sad, which one could say is Budnik's motto. It doesn't imply wallowing in sadness, but rather understanding that acknowledgment is the first step in processing that emotion in a healthy way. Some of the strips are in black & white, which is not the best look for his work, but later iterations are printed in color. He's not precious about them; he shrinks and slaps three or four of these four-panel journal comics on a single page as a temporary collection method before he will likely collect them in another edition. In one issue, he tackles Hourly Comics Day, an exercise that's exactly what it sounds like. Set in February of 2017, in it he tries to process the initial horrors of the Trump administration while still creating new therapeutic goals for himself.

Budnik, through the process of writing strip after strip, has also become a better writer. He has dropped some of the more poetic aspects of his work in favor of a blunter, plainer approach that suits him better. There is no artifice here, just blunt self-expression. He's a sharper observer of his environment and writes absorbing, funny anecdotes, like one about being in a bar with a friend when she suddenly gets hit on in a massively inappropriate way by a random guy. Budnik conveys the suddenness and randomness of the event with humor, but there's also an underlying sense of worry about things escalating. In a later issue, he talks about how his relationship has not only allowed himself to open up and let someone else in, it's also given him the desire to listen to and understand others in a way that was always difficult for him. One can see this extend to his friendships in other strips, where it's obvious that Budnik really hears what they're saying.

In a later issue, he makes fun of his own recovery in a strip where he says that before he started therapy, he spooned a small amount of hummus onto a plate. Now he simply dips the carrot right in, "because I am alive." Budnik's willingness to engage in a humorous way with topics like this is one reason why his strips are so compulsively readable. He works in a form that's built to deliver punchlines. Budnik also reveals a lot of details of his therapy to the reader, including trying EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy), which seeks to focus on traumatic memories from a safe vantage point in order to redirect their influence. Even as Budnik simultaneously gained confidence in what he was doing and feared that his depression might return, his craft rose to another level in 2017. His lettering, which was always fine, suddenly became more refined and added a decorative as well as utilitarian touch to his work. Budnik understood that there will still be bad days, and there was certainly trouble and heartache ahead of after the last strip here (July 2017).

Like John Porcellino and his devotion to his King-Cat zine even at his lowest points, so too did Budnik keep his journal going. He may have felt awful while he was doing it, but he still did it, day after day. In therapeutic terms, it's "opposite action" in a real sense; depression often leads one to do absolutely nothing, but doing something instead can help. It's not a substitute for therapy or medication, but self-expression and the understanding that drawing is a pleasurable activity clearly led Budnik in the right direction. Along the way, he's become a better draftsman and writer. The mini Peer (Believed Behavior,), a Risographed comic, is not explicitly autobiographical, but its exploration of traumatic childhood memories is raw, as though it came from an EMDR session. Even more disturbing than the trauma he experienced in gym is the negative self-talk the child in this story starts giving himself. It's one of the rare times I've seen Budnik do something that isn't autobio, and there's a powerful sensitivity as well as a relentless attention to the tiniest of painful, lingering details. The more that Budnik focuses in on those details, the more universal his stories become, and he's made it clear in his author's statements on books that he hopes that others can find some kind of value in the stories he tells.