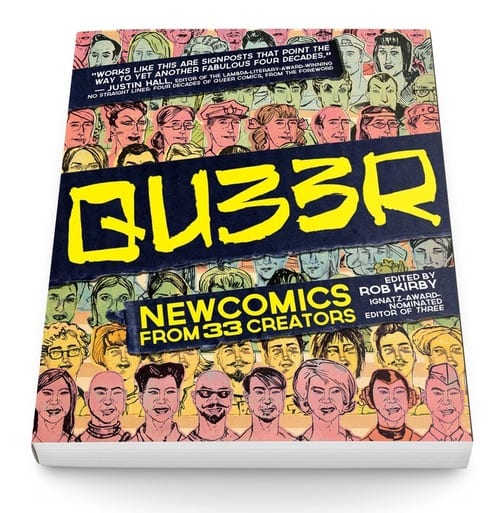

Rob Kirby has been editing comics anthologies for over twenty years. Starting with Strange Looking Exile in 1991 (which included Alison Bechdel & Roberta Gregory), and continuing with Boy Trouble through the '90s until 2006, and Three in the past couple of years, Kirby has published them in the formats of mini-comics, comic books, and trade paperbacks. Kirby has always had one eye on quality and another eye on diversity, trying to get as many different points of view and styles as possible into his queer-themed anthologies. At the same time, it's always seemed like he was trying to push his contributors into doing their best work for his anthologies, because diversity alone wasn't enough. He's also long had an eye for emerging young talent, encouraging young cartoonists to submit to his anthologies while attempting to push them past their limits as creators.

What's interesting about Kirby is that while he's been a prominent queer cartoonist and editor for nearly twenty-five years, he also sees himself and the artists he publishes as part of the greater alt-comics scene. The queer alt-comics scene is one that has evolved parallel to the straight underground scene, with surprisingly little crossover or awareness between the two audiences. Of course, that's never been the case for Kirby himself, who grew up reading Weirdo and worked to have John Porcellino distribute his comics through Porcellino's Spit And A Half. It's always been part of his mission to find ways to connect the two communities without compromising the identity of the queer community. This is one reason why the 2012 Justin Hall-edited No Straight Lines was such a landmark. While that totally uncompromising survey of queer comics not only won a Lambda Literary award, it was also nominated for the (quite mainstream) Eisner Award. Kirby's new anthology QU33R is very much a reaction to and extension of No Straight Lines. If the latter collection represents the past of queer comics (including the very notion of what it is to be queer in the modern day), Kirby wanted to assemble an anthology that provides a snapshot of its present.

Kirby's previous anthology Three was aimed at alt-comics readers in general, not just queer readers, even though its content was unapologetically queer in nature. He chose three stories for each issue, and the results were strong on an issue-to-issue basis. For QU33R, he essentially turns what would have been the fourth issue of Three into something bigger, something that represents his vision of an anthology that would equal the best anthologies of the day, but with a roster of cartoonists highly underrepresented in alt-comics circles. Again, he faces some constraints in that he wants to include a broad range of experiences in terms of age, race, gender identity, and sexuality. Some of the work here is notable more for the creator's life experience than the quality of the work itself. Some of the work is simply not as strong and it hurts the anthology's overall impact. There's no question that Kirby succeeds in providing that snapshot of queer comics at a time when more queer comics are getting either mainstream interest and/or being published by mainstream publishers than ever.

Let's take a look at the actual comics in the book. If there is a theme to be found in the anthology, it might be "pause and reflect." A number of the stories deal with coming-out stories, or key autobiographical moments from the cartoonists' lives. Others deal with larger cultural experiences. These tended to be the stronger stories in the book, for the most part. Kirby is wise to start off with Eric Orner's "Porno", a haunting story about guilt, coming out, self-hatred, the bonds (and chains) of family, and how for so many queer folk, these are literally matters of life and death. Using a line that alternates between sketchy and feathery, Orner talks about one of his biggest regrets from his youth and how it may have indirectly led to the death of an acquaintance in a story told using his rocky relationship with his father as a framing device. It's a powerful, solemn story that avoids navel-gazing and deserves any kind of "best short story" awards that exist for comics.

Having gained the reader's attention, Kirby shifts the aesthetic to Annie Murphy's remarkable family photo-comic, in which she reinterprets photos and history to discuss two key female relatives--one who helped her mother survive growing up and one who helped Murphy with that same process. It's a story about depression and overcoming one's circumstances through the power of empathy and understanding. The white, hand-written lettering and images on black add to this sense of discovering someone's old photo journal in an attic somewhere. It's a reflection on survival and the forces that get us there.

MariNaomi's spare line is augmented by a bright color palette in her "Three's A Crowd". It's an autobiographical story about how fear chokes emotions. It details the events of a party where she had sex with her then-girlfriend for the first time, but as part of a threesome with another woman. While she doesn't downplay the erotic charge of the experience, the real meat of the story comes when her lover expresses her feelings for her and the artist responds by literally laughing in her face. It's a story about a fear of intimacy, a fear of letting go, something that's augmented by the way she distorts figures to match mood.

The next story is a short from Ed Luce starring Eiffel, a character from his Wuvable Oaf series. In it, he and a friend go to a black metal concert and survive the mosh pit. It adds much-needed levity to the book, and is full of amusing cultural nods. Add the sheer energy of his line and the explosive use of color, and you've got an incredibly strong quartet of stories to open the anthology's first 1/5th. Things get a bit wobbly after this, alternating between stronger stories, weaker ones, and contributions from good cartoonists that feel all too short.

For example, while I appreciated the metaphor Dylan Edwards uses in talking about the Transformers with regard to "gendering" toys, the story itself is a bit too on the nose and didactic. The very next story, Diane DiMassa's anecdote about playing with a feminine boy as a youngster and encouraging him to be himself (or herself, perhaps) is a shorter, sharper way of getting at a similar point. It also doubles as a way for her to talk about "finding her people" even as a young person and defying the irrational homophobia of her mother.

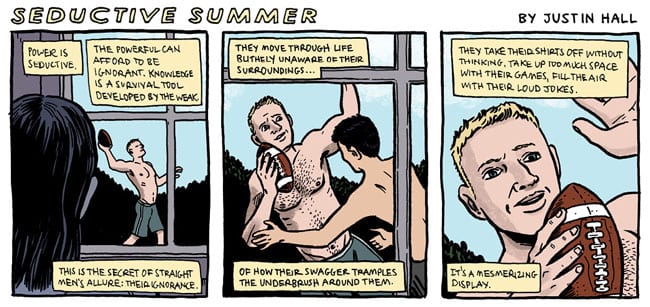

Justin Hall's "Seductive Summer" is one of the tentpole pieces of the book. It's an epic, heart-on-sleeve account of the desperation of young love and how such an experience can blind a person to warning signs regarding mental illness in others. It veers from romantic to harrowing at the drop of a hat and is the epitome of the book's unspoken theme of looking back on key events from the perspective of experience. This is followed by the thoroughly silly "Just Another Night In Carbon City" by Jennifer Camper, a noir-style story about a hitwoman and the woman she falls for while on a job. Camper's style is ill-suited for such a noir tale, giving the story an absurd tone she perhaps was not intending. Erik Kostiuk Williams's short piece about watching RuPaul's Drag Race at bars as a sort of "gay equivalent of watching the football playoffs" is typically funny, smart and sharp. I would have loved to have seen a longer piece by Williams, who is an enormously promising young cartoonist.

The following piece, Kris Dresen's "Chop Suey", kills the momentum of the book. It's a dull, self-congratulatory lunch conversation between two women, one in which the lack of context destroys any kind of reader hook. The static, talking-heads approach combined with weird facial stylizations makes its ten pages drag by. Thankfully, that's followed by Tyler Cohen's "primazon" story, one where female forms with unusually decorated faces and heads go about their day. The story revolves around a couple who are working with metals, as one half of the couple arrives to take a walk with the other half and their child. It was difficult to discern whether the metal bracelets they were working with had a more sinister purpose, given that one of the women bought a severed arm with a bracelet on it, but the tone of the story was matter-of-fact and even quotidian.

Kirby wisely lightens the mood at this point with a jam between Camper and Michael Fahy about a doomed young would-be art student. Trading off every three panels, the pair weave together a remarkably coherent, violent, and funny story with a cruel ending. Such jams are a tradition in Kirby anthologies, and he really picked the right pair to do the concept justice. Fahy followed up with his own striking images: found BDSM polaroids that he drew, images of poet Frank O'Hara, and "Hazily-Remembered Drag Queens". Along with Edie Fake providing a surprisingly straightforward (yet hilarious) set of gags surrounding a sex club and Jose-Luis Olivares using daring cultural cartoon appropriations in a thoughtful and vulnerable manner, these are transitional pieces designed to give the reader something bright and interesting to look at in-between longer stories.

In this case, the next tentpole piece was Steve MacIsaac's "Vacant Lots", an autobiographical story that explores past bullying and gay-bashing, feeling out of place, and wish-fulfillment revenge fantasies. It's a bracing piece; the reader can feel the artist's rage bleed from the page in a sequence where he seems to take brutal revenge on a former tormentor, only to realize that violence is only ever circular and pointless. MacIsaac's figures are a bit on the stiff side, but he breaks through that with the fistfight scene, even if the way his figures interact in space isn't quite right in a naturalistic setting.

Rick Worley's piece is another highlight of QU33R. It's a poetic memoir about four lost loves, told out of order. The 23rd panel comes first, followed by the 10th and then the 18th. However, the story as told still makes sense, especially because of Worley's hauntingly plain narrative text. Indeed, telling the story out of order creates a juxtaposition of memories, as the stories of different relationships bleed into one another as Worley jumps back and forth in time.

Christine Smith's silent "Life's But A Walking Shadow" has a clever central conceit (female form, male shadow) that is difficult to follow because of Smith's relentlessly stylized line, which resembles an animation storyboard more than a comic. The panels are so cluttered and dissonant that it is hard to find the narrative through-line. On the other hand, the simplicity of Carlo Quispe's line in "Political Will" makes it easy to follow despite similarly jamming a lot of detail into each small panel. Of course, Quispe smartly monochromed background characters and only made foreground characters with dialogue get extensive use of color. It's a great story about the intersection between political acts and personal politics, especially in how they intersect with relationship to HIV-status, polyamory, and protests.

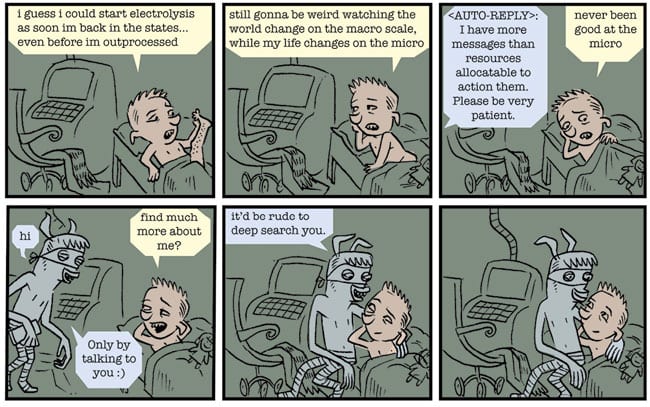

Kirby then smartly transitions to another tentpole piece: Andy Hartzell's visual imagining of the conversations between a gay but closeted army intelligence analyst and a free-information hacker. Using a cartoony style, Hartzell creates an environment where the masked hacker and the analyst, who was strongly starting to consider gender transition, "interact" in fascinating ways: in bed, in a virtual fort, behind a "privacy curtain." It's a story about secrets: having them and needing to let them go. After that heavy story, Carrie McNinch's "Toot Toot Beep Beep" is a sweet memory of her first kiss. Her clear, distinct line looks great in color, but I wish this talented memoirist had had one of the longer pieces in the book.

Kirby's own "Music For No Boyfriends" is the usual excellent fare from the artist. It's an autobiographical story that relies heavily on memory, music, and a casual but jarring admission from a lover that essentially destroys an idyllic dinner. Kirby's rubbery drawing style and mixed purple/grey palette adds to the sense of wistfulness. Sina Sparrow's story is similarly a memory about a relationship gone wrong because of unhealthy power dynamics. It's interesting because it's far more sexually explicit than most of the stories in the book, but its use of zip-a-tone and other color effects gives it a slightly cartoony feel. Ivan Velez Jr. keeps this run of stories about hook-ups going with the sole superhero story in the book, which is not a surprise given Velez's background in mainstream comics. In this story about a young hero who has just earned his hero card, he hits a local superhero bar and discovers he's popular as "fresh meat." The splashiness of the outfits and larger-than-life nature of the characters is a perfect fit for another sexual explicit story. In both instances, the sex scenes are crucial for establishing characterization rather than simply attempting to be titillating.

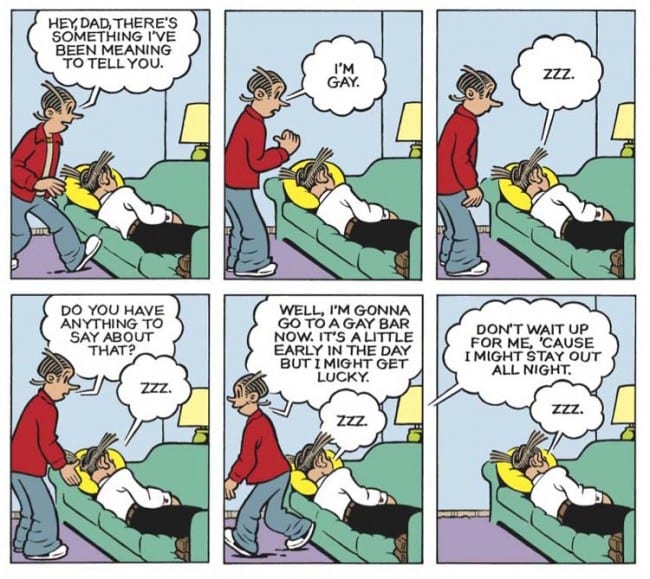

Howard Cruse's Blondie send-up is an exquisitely drawn, amusing space-filler; again one would have hoped for something longer from such an important cartoonist, but so it goes. Kirby's collaboration with openly gay pro wrestler Terrence Griep is entertaining as a novelty piece, thanks to Kirby's line and the colorful nature of pro wrestling itself. Craig Bostick's "Guitar Bass Drums" is a brilliant short piece about three members of a band and the sexual politics of adding a new member. Each page is narrated by a different member of the band and is color-coded. Bostick's been making great comics about musicians for years, but there's a beautiful simplicity of structure in this piece that elevates it above past efforts.

Amanda Verwey's anecdote about having a crush on comedian Paula Poundstone unexpectedly turns into a story with a jab of a punchline; her slightly grotesque drawing is a nice counterpoint to the more typical cartoon art in much of the rest of the book. Nicole Georges' account of going on a blind date with Grief, the emotion itself (appearing to her as a panda), is the rare piece in the book that would have looked much better in black & white. Her color choices in the story overwhelm her line without adding much to the story in either a narrative or emotional sense. David Kelly's comics are light-hearted and on the fluffy side. Marian Runk's series of four-panel vignettes are another highlight of the anthology, as her expressive pencil drawings and restrained use of color offer an oasis of quiet, quotidian moments.

Rounding out the book, talented master of style Sasha Steinberg has a funny story about a drag queen invading a "Wal*Mark" and using her superpowers to transform a homophobe into a unicorn and the store itself into a fantasy paradise. This is another piece that mostly adds color and flair to the anthology, one that's not as serious as Steinberg's other projects. Jon Macy snaps back into the "pause and reflect" idea of the book in talking about his heroes in literature and music, both in terms of characters but mostly the artists themselves. It's a story about being an outsider in more ways than one, as both a gay man and an artist who struggles with little recognition. Macy can't seem to help himself in going overboard with shadows and a slickness in style, along with a slightly overwrought narrative voice, but his sincerity is never in question. Finally, L.Nichols' brightly colored account of her struggle with the identity of being gay, of coming out to others, points to the collection's mission of addressing queerness as less a binary state than a fluid one--both in terms of desire and identity.

Kirby does an admirable job of keeping the anthology flowing, spacing out longer pieces and generally attempting to make thematic connections in the way he sequences the book. In the interest of full disclosure, I should note that Rob & I are friends and we talked about the process of editing QU33R . He told me that there were many other cartoonists who he discovered a bit too late to include, and mentioned Sophie Yanow and Laurel Lynn Leake by name. Other cartoonists on his wish list declined to participate, or were unavailable.

QU33R unquestionably succeeds as a wide-ranging survey of queer cartoonists at this point in time. Kirby strove to make it as diverse as possible, reaching back into the past with artists like DiMassa and Cruse and linking up to the future with cartoonists like Williams, Olivares and Murphy. Kirby had an incredibly difficult balancing act to pull off, as he wanted to make the anthology accessible to all readers without compromising its identity, representative of a broad swathe of queer creators, and to be of a quality that would rival its contemporaries. While he succeeds admirably regarding the first two points, QU33R doesn't quite get there on the third. There are just a few too many fluff pieces and flat-out clunkers to put it in the top rank of all-time great comics anthologies. That said, there are a handful of brilliant pieces in the anthology that I'd stack up against entries from any other anthology (the stories by Orner, Murphy, MariNaomi, Luce, Worley, Bostick ,and Hartzell) and several other very good pieces as well (by DiMassa, Hall, MacIsaac, Williams, Olivares, Fake, Cruse, Velez, Kirby, Nichols, Steinberg, Quispe, McNinch, and Cohen). That's a good batting average for nearly any anthology, especially one that had so many competing factors at work in its creation.