Dakota North matters.

Dakota North matters.

Dakota North? Yep. The bimonthly series that lasted a grand total of five issues? The same. The one written by a woman (Martha Thomases) with no experience writing comics and drawn by a dude (Tony Salmons) with little experience drawing comics? Bingo. Didn’t Larry Hama have a hand in that mess? Sure did. Dakota North … she’s like a detective or something? She runs an international private security agency specializing in cases of malfeasance within the fashion industry. International? (Yes, she has offices in New York, Paris, Rome, and Tokyo.) Doesn’t she always wear a jumpsuit with high heels and ride a motorcycle? Well, not always, and the bike is an antique, a 1939 BMW. No superpowers, right? That's right! Is the series her first appearance? First. So, an original character? Very. Well, the jumpsuit and heels make sense, but the rest …

When Dakota North debuted—cover date June, 1986—the only other female-led titles being published at Marvel were the last issue of a Firestar limited series and Misty on the Star Comics imprint, targeted at younger children. Vision and the Scarlet Witch was in the last quarter of its twelve-issue limited series run, and while Scarlet Witch was a co-headliner and Vision isn’t, technically, a guy, her name still came after his. DC fared slightly better with three female-led titles, Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld, Elvira’s House of Mystery, and The Legend of Wonder Woman. Three months prior, DC had canceled the long running Wonder Woman on-going series with issue #329 (a ‘Crisis’ crossover) with a storyline marrying her off to Steve Trevor.

Away from the mainstream publishers, female representation in comics remained sparse. Archie Comics was the leader, by far, with five female-led titles. Fantagraphics released Love and Rockets #17 while Renegade published Ms. Tree #30. One other female-forward comic to come out at that time is Whisper #1 written by Steven D. Grant with art team of Tim Burgard, Rico Rival, and Wendy Fiore, which was published by First Comics. Comic Vine described Whisper as a ‘ninja-esque’ character, perhaps the ‘esque’ meaning, like Dakota, Whisper favored form-fitting clothing when she tooled around town.

As shocking as it is to imagine the lack of female representation in comics … in the mid-1980s, Dakota North went one heel-toe step further; she arrived as a fully-formed character existing outside Marvel continuity. Think about that. Here was a new character in her own standalone series sans super powers or superheroes published by Marvel Comics. Think. About. That. No good deed goes unpunished! A little over a year after her eponymous series is cancelled, Dakota was subsumed into the maw of the Marvel Universe when Jim Owsley i.e. Christopher Priest wrote her (and her brother Ricky) into Web of Spider-Man #37 where she assisted in the capture of The Slasher, a serial killer who murders fashion models.

Web-heads (and horn-heads) must have been all a tingle when Marvel announced Web of  Spider-Man #37 was being reprinted along with some late '90s Brubaker and Rucka Daredevil in “Design for Dying”, in a new trade paperback containing the full run of Dakota North … because that’s a thing, right? Indeed it is, but seriously, who asked for this? “The Demon Bear” story from New Mutants was recently reprinted, but that was (probably) intended as a tie-in before the movie was bumped to 2019. So why Dakota North? Why now? Maybe there’s some fashion designer in trouble in season 2 of Luke Cage? Maybe the MCU needs more able-bodied IPs after the ‘snapture?’

Spider-Man #37 was being reprinted along with some late '90s Brubaker and Rucka Daredevil in “Design for Dying”, in a new trade paperback containing the full run of Dakota North … because that’s a thing, right? Indeed it is, but seriously, who asked for this? “The Demon Bear” story from New Mutants was recently reprinted, but that was (probably) intended as a tie-in before the movie was bumped to 2019. So why Dakota North? Why now? Maybe there’s some fashion designer in trouble in season 2 of Luke Cage? Maybe the MCU needs more able-bodied IPs after the ‘snapture?’

Dakota North is remembered, if it’s remembered at all, as a goofy ‘80s comic tchotchke, proof that the halcyon days of Jim Shooter’s Marvel Comics tenure were a license to print money and take (somewhat) calculated risks. A less cynical view would be to see Dakota North as a testament to Larry Hama’s influence at the ‘house of ideas.’ And yet something abides in this story about a scarlet-haired, jumpsuit-wearing, high-heeled heroine who crosses continents in search of her bratty brother and his traveling companion, a sixteen-year-old female model, and a pen full of nerve gas with the potential to wipe out every living soul in a few city blocks. And yeah, like any (super)hero worth her salt, Dakota does indeed ride a motorcycle out of a service elevator and into a New York for a fashion shoot. She also rides the same motorcycle up an escalator in a chic Manhattan department store. She shakes off sheikhs, battles a bloodthirsty raptor, and outfoxes a monster truck in Rockefeller Center. And does so with fierce aplomb, style, and a sense of adventure. Dogged and defiantly independent, Dakota North is a fashion-forward comic whose style never caught on.

To say Dakota North was an outlier is a disservice to outliers. The moment Ms. North starts stylin’ is when the ground began to shift under comics—Dakota North #3 comes out the same month as Batman: The Dark Knight #4 and Watchmen #1. Now, it would be an act of hubris and hyperbole to say two neophyte creators like Thomases and Salmons (even with a wily vet like Hama at the helm) would come close to equaling the murder’s row of Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, Lyn Varley, Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins. Proximity to greatness does not make something great, and Dakota North is not on par with the craft, canniness and inventiveness of those '80s masterpieces. And yet what Dakota North lacks in artistic pedigree it makes up for in chutzpah, idiosyncrasy, and how it outdistances its peers in representation and female agency. So subtle is it in its subversion, representation, and agency it almost passes as insignificant, almost. What Dakota North wanted was be seen as an equal in her world and the world writ large. She was a disruption of the status quo and way ahead of her time, perhaps even today. That’s why Dakota North matters.

***

Martha Thomases hadn’t written a comic before Dakota North (nor since). She was working as a freelance writer in New York City for comedy magazines like Spy and National Lampoon. She had also started her own magazine with her husband, John Tebbel, Comedy. While on assignment for High Times, she was introduced to writers and editors working in comics. In an email interview (August, 2015) she said, “I met people in comics, including Denny O’Neil … and through Denny, I met Larry Hama.”

Pause. Did you catch that? August, 2015? I’ve pitched a revisit of Dakota North several times to several different editors at several different websites. They all said no. I was close a few years ago when I pitched the idea of an oral history of Dakota North. I emailed Thomases, Salmons, and Hama. I exchanged a Facebook message and an email or two with Hama which went nowhere. What contact information I found on Salmons turned out to be, not surprisingly, a dead end. Thomases was the only one to respond. Unpause.

Hama seems to have been the prime mover on what would become Dakota North. Thomases says they would talk about “how to make comics for girls/women.” Hama brought up his interest in fumetti comics, “especially the Spanish soap-opera kind, with a single panel on every page. We talk about doing something like that [with] Mary Wilshire as the artist. But it doesn’t work out, so Larry and I brainstorm more about what makes a woman heroic. We talk endlessly. I want someone who is tough and no-nonsense and practical, but not stereotypically masculine.”

In what’s best described as a charming anecdote involving the men’s room at Marvel Comics, Salmons, in The Factual Opinion, told cartoonist Michel Fiffe, “[Dakota North] was totally Larry Hama's idea. He hired me cold at the offices one day. We were zipping up at the urinals, appropriately enough, and he told me to bring my stuff into his office. He told me I could draw better than most of the guys working there, the first and only editor to ever say anything of the like, but was emphatic that my storytelling 'sucked.” In the year plus we worked on Dakota North he showed me why and what's better, how to fix it if I would take the advice. For me it was the beginning of the lengthiest, most troubled, and most rewarding working experiences in comics.”

Comics are weird and comics publishing more so. Why Hama plucks these two tyros almost off the street to create a comic for Marvel is either quaint, cruel or downright cliché—it’s the kind of story a trite response like “it was the '80s!” would almost explain, but doesn’t. Salmons says, “The book and characters were full blown and Martha Thomases was as green at writing something like a regular series as I was at drawing one. It was a rough ride.” Thomases: “Without Larry, I would not have had a clue about how guns work, how fighting works … He taught me about pacing and plot and how there couldn’t be page after page of people sitting and talking (a lesson I still need to learn).”

Thomases and Salmons’s rawness makes Hama’s role seem more like an impresario than an editor. Thomases says she and Salmons didn’t spend much time together “face-to-face” and that as “a writer of prose, I had no clue about how to write instructions for an artist, or how much could be put into a single panel. I didn’t know how to indicate camera position or point of view. [Hama] would tell me, “Write things that are fun to draw” and I would have no idea what that was unless I asked Tony.” For his part, Salmons seems as clueless about comics storytelling as Thomases. He recalls, “I redrew more work under [Hama’s] editorship than any other place I've worked but he always showed me why. It was never arbitrary or just because he didn't like it. It was what I'd wanted, to find my way through stories. He could speed up the pacing or slow it down, focus on a character versus an action and always make the image serve the story. That is, keeping in mind the continuity before the image in question and its relationship to the images after to form a coherent whole; keeping this in mind both within the scene and the longer continuity of the story itself.”

A writer who didn’t know how to write comics and a cartoonist who didn’t know how to draw comics and an editor willing to give it a go … only in comics, only in comics.

Given the circumstances, five issues should be considered a minor miracle. ‘Fashion Statements’, the name of the Dakota North letter column, appears in the last two issues. The fan reaction (at least what made it into the column) was positive. Thomases says, “We didn’t get a lot of mail, alas, but what we got was good.” According to Thomases one fan who saw Dakota’s merit was another independent and fashionable woman, “I was told that Tina Turner was interested in the movie rights. She would have been awesome but, I think, too old. It would have been a different story, which might have been a fabulous tale, but not the one I was telling.”

Turner’s interest in the character and the series speaks to its feminism. It’s easy (and lazy) to think words like ‘agency’ and ‘representation’ are recent entrants to the zeitgeist as (slightly more) female-led popular entertainment appears and is accepted in popular culture, however slowly, as equal. When asked about this, Thomases was quick to say, “I hate to tell you, but feminists have been having the discussions about body image and macho jerks and all that since the 1970s. It’s an indication of how resistant the mainstream culture is to these ideas that they still sound current (and it’s why feminists my age sometimes feel like we’re beating our heads against the wall). If you read Ellen Willis and Karen Durbin (both big influences on me at the time), you’ll see these issues discussed at length.”

“Still sound current …” The fact the ratio of ‘stories about/for men’ and ‘stories about/for women’ has been either lopsided or underappreciated in pop culture for forever is what makes Dakota North so fresh three decades after its initial publication. Setting Hama aside, perhaps it’s Thomases and Salmons’s naïveté which imbues Dakota North with a timeless quality, a kind of DIY purity of instinct over experience. Perhaps they didn’t know any better or know what they were doing. Or they had nothing to lose. Given the dearth of female-led comics at the time, any representation makes the series feel more avant-garde, but only if the work stands on its own. Dakota North deserves more than a participation medal. It deserves, at least, to be remembered/represented, part of the conversation of great comics of the 1980s.

***

Page one of Dakota North #1 is a distillation of what Salmons and Thomases learned from Hama about making comics and serves as a thesis statement for the entire series. What they've come up with is cleverly designed subversion that presents three lies about Dakota North: (1) Dakota’s deference to action, (2) the possibility a man, other than John Rambo or Edgar Frog, can rock a red sweatband, and (3) that anyone, in the evolution of human speech, has ever said, “Eat lead, geek face!” The fashion of Dakota North is surfeit; its style, its power, is in its subtext.

Salmons's composition creates a frame-within-a-frame-within-a-frame that calls attention to itself about as subtly as the “BLAM BLAM BLAM” sound effect. The series title sits at the top of the page balanced off by the issue title at the bottom, “Design for Dying”. Letterer Jim Novak gives the word ‘Dying’ a spooky cast that would also have played well in Elvira’s House of Mystery, ditto the title itself. Mounted to the left hand side of the page are the heads and names of the principal players in the series. The simple lines of these head shots give quick sketch of each character. Flat and fast, the faces form a scorecard that looks like a discarded head studies for a never-published strip by Will Eisner or Chester Gould.

Inside the top right corner of the (second) frame, the panel proper, is half a ‘T.’ Trapped within this (third) frame are two figures, a man and a woman, easily identified, thanks to the roll call on the left, as Mad Dog and Dakota. The pair seem to have been surprised by the looming ‘T’ in the foreground. Mad Dog’s stance is open. His legs are spread wide. He thrusts his gun forward as his other arm falls backwards. There’s no control in Mad Dog’s posture, only instinct, adrenaline and the drive to survive. He yells, “Dakota! Look Out!” and then utters his immortal phrase, “Eat lead, geek face!” By contrast Dakota’s face is as inscrutable as the Sphinx. Is she surprised by the situation? How loud the gunfire is? Is she, like the reader, attempting to parse “geek face”? Her gun points away from the action as she looks over her left shoulder. It appears Mad Dog fired prematurely and dove in front of Dakota to defend her as she takes up a defensive position to protect him. Her heels are set firmly on the floor. Although he does warn her, Mad Dog doesn’t shout out any ‘white knight’ bullshit about saving Dakota or keeping her safe. It’s a showy page, for sure, and it is also a complete and total head fake. The next page reveals the threat was only the outstretched arm of a pop-up target, “Congratulations Mad Dog,” says Dakota, “you just trashed a bag lady.” Like the best comic book violence the danger is imaginary, there’s an eye-rolling pun and the situation is, as always, consequence-free. Salmons and Thomases may have been first-timers, but they sure knew how to make a smart first impression.

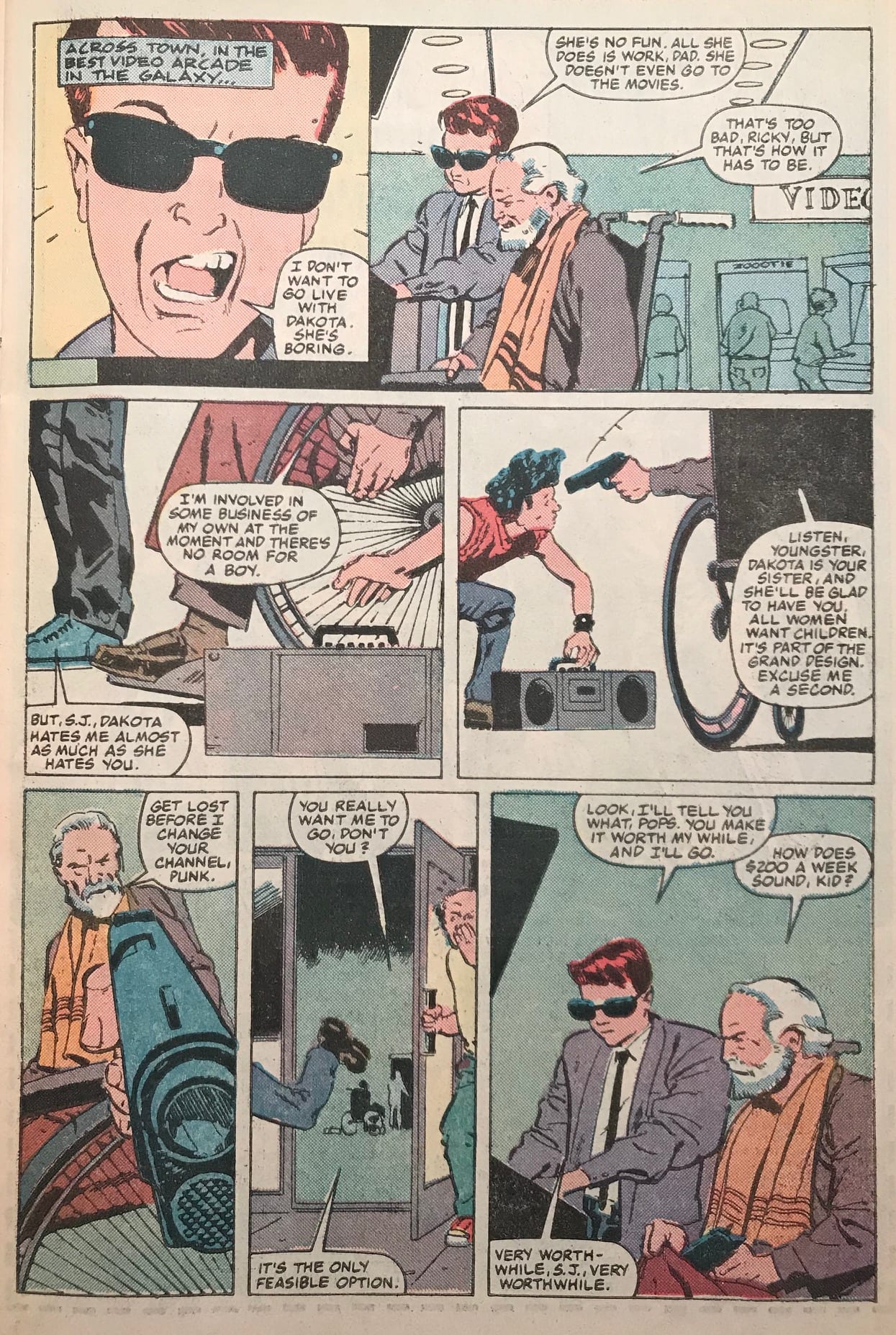

There are enough 1980s signifiers in Dakota North to fill an arcade, perhaps even “the best video arcade in the galaxy” which is where Dakota’s brother, Ricky, and father, S.J., are introduced. S.J. is trying to convince Ricky to live with his sister because S.J.’s “involved in some business of his own.” Because, yes, of course, an arcade—sorry “the best arcade … in … the … galaxy”—is as good a place as any to tell your twelve-year-old son you’re sending him to live with his sister (without asking her first, natch) for specifically vague reasons.

This being the 1980s, S.J. and Ricky have brought their boom box with them. How the reader knows it’s their boom box is because S.J. pulls a gun on a would-be thief who attempts to steal said boom box. Salmons composes a panel from the thief’s POV so the gun dominates half of the frame. S.J. says, “Get lost before I change your channel, punk.” Another pun! Ricky, who must be used to his wheelchair-bound father cracking wise and pulling a firearm on would-be criminals, blithely continues to play his game in his too-cool-for-you suit, skinny tie, and sunglasses.

The mishigas of the attempted boom box burglary interrupts S.J.’s rationale as to why Dakota is duty bound to host her brother. According to papa North, it’s not due to any familial obligation she may have for her younger sibling, no, it’s because of her ovaries and her lady brain. S.J. tells Ricky, “Dakota is your sister, and she’ll be glad to have you. All women want children. It’s part of the grand design.” So few words, so much baggage. Give Thomases credit, she's able to slip some solid gold patriarchy into the middle of an attempted robbery and a textbook case of latchkey parenting. And good on her for never explaining why S.J. is disabled. Like the boom box, the handgun and so much else, S.J.'s wheelchair just is in Dakota North. It’s easy to (dis)miss nuance when the situation is this ridiculous. Dakota isn’t in the scene, but the action centers on her and exemplifies the gender inequality she has to deal with in her family.

In addition to tactfully pointing out institutionalized patriarchy, Thomases also upends gender roles. When Mad Dog’s not having his band over to practice in Dakota’s apartment, he keeps house. He makes sushi, cleans, and answers the telephone. Mad Dog is more than a dogsbody, he’s a domestic. While his boss travels the world, kills dudes and drives fast cars, he pops his collar, sports his dumb red headband and plays house. It’s Dakota who has both agency and "the agency".

Mad Dog’s main mission seems to be as an interpreter for the men in Dakota’s life. He also takes the initiative to add some light matchmaking to this list of duties. The will-they-won’t-they-who-cares romance in Dakota North revolves around an NYCPD detective, Amos, who acts more like a spanked puppy than a man of action. For instance, when Amos, S.J., Mad Dog, Dakota and Dakota’s latest client, Major George C. Cooper—he’s the person who gives the pen full of nerve gas to Ricky, in the first place, as a retainer after losing $200 to him in a poker game—have gathered, at midnight, in the basement of Dakota’s townhouse to figure out Ricky’s whereabouts. The last person to see Ricky was Mad Dog, who told him to go “play in traffic … I’ve got typing to do.”

In order to insure the safe return of Ricky AND the pen full of nerve gas Dakota’s going to have to take matters into her own hands. She quickly comes to this realization and freaks out. She splinters a couple of those pop-up targets with some swift kicks before Amos steps in to console his lady love by grabbing her from behind. Dakota breaks his hold and says: “Let me go, Amos! I don’t need your police protection.” Dakota walks out of the room with the bon mot, “You guys can stay here and talk all night, you do that extremely well.”

Since it is midnight, and this bull session does look like it’s going to be an all-nighter, Mad Dog makes coffee. A cowed Amos approaches Dakota’s ‘boy’ Friday and says to him, “Sheesh! What’d I say, Mad Dog? That move always works for Don Johnson!” The factotum says to Amos, “Crockett couldn’t score with my boss lady, Mr. Detective. I keep telling you, Amos, be your own cool self. She’ll love it.” Poor Amos, another in a long line of strivers who thinks all it takes to be Don Johnson is some well-meaning restraint and orders. Good thing Mad Dog brings an enlightened outlook to the group and apparently (his?) skateboard. Even when Thomases is overtly showing Dakota taking charge, she tempers her point with a punchline that (almost) takes away Dakota's power.

Here, again, Thomases is at her craftiest as she couches a discussion of gender politics with a reference to the macho-i-est ‘macho jerk’ jerk of 80s TV. If “Crockett couldn’t score” with Dakota, than what chance does lantern-jawed Amos have? Later, Amos, ever the charmer, will ask Mad Dog: “Do you think your boss will ever give me a tumble?” Romantic, no? What would Don Johnson do? Not ask the male assistant to the woman he wants to hook up with for advice, that’s what. Like most of the men in Dakota North, Amos is impotent, a chastened little boy, unable or unwilling to act.

Thomases’s breezy style, although thick with clichés, serves as a way to deflect from the more serious subtext of these scenes. It’s too clever by half, but is the humor an asset or an obstacle? Does it diminish Dakota’s agency or add a layer of pluck and hyper-awareness of her ‘place,’ in the world? Could it be both? Perhaps it’s enough to say women act and men don’t in Dakota North. To a man, none of the male characters could be mistaken for men of action. They are either bumblers, dupes or pushovers. Dakota’s only worthy opponent is Cleo, a hackneyed ‘dragon lady’ type, who pulls all the strings in an attempt to get the poison pen from Ricky and kill Dakota in the process. It’s Cleo who hires assassins and a raptor-wielding sheikh to kill Dakota, and Thomases clearly had plans to set Cleo up as Dakota’s nemesis. The last issue ends with Cleo holding a gun out of S.J.’s line of sight while she conspires and canoodles in his lap. In Dakota North, women act and men are, all the way down.

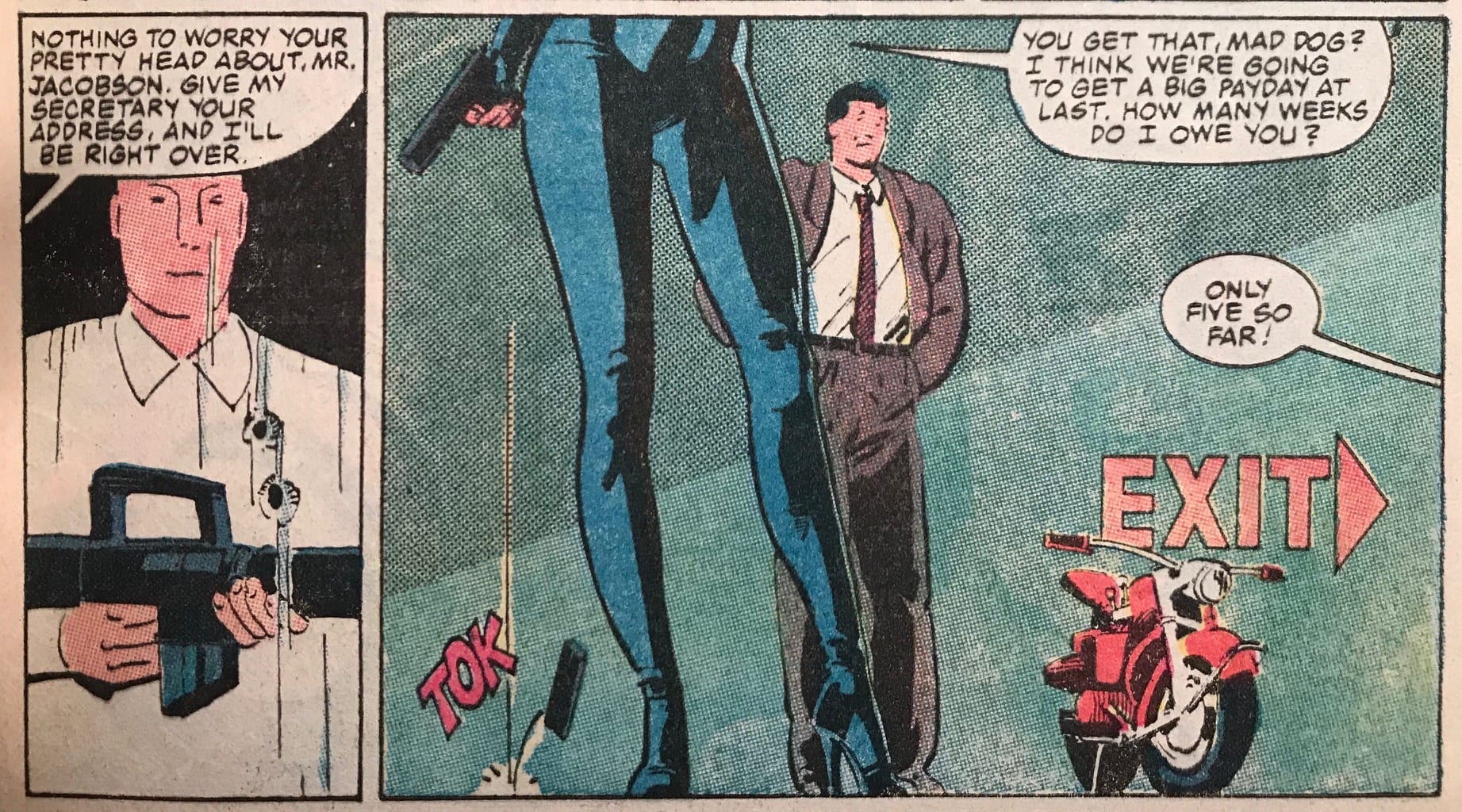

Besides Mad Dog, the only other man who ‘gets’ Dakota North is Fabio lookalike and fashion designer, Luke Jacobson. Like Mad Dog he’s a fool and much of what he does is played for laughs. He dances around his studio to Donna Summer and imparts knowledge about the critical community to his assistant, Anna, “print a few ducks on a scarf and the critics will call you a genius.” He also knows what makes a certain international investigator an inspiration, “The woman of my dreams fears nothing and no man. She is strong. She is free. She is just like Dakota North.”

Besides Mad Dog, the only other man who ‘gets’ Dakota North is Fabio lookalike and fashion designer, Luke Jacobson. Like Mad Dog he’s a fool and much of what he does is played for laughs. He dances around his studio to Donna Summer and imparts knowledge about the critical community to his assistant, Anna, “print a few ducks on a scarf and the critics will call you a genius.” He also knows what makes a certain international investigator an inspiration, “The woman of my dreams fears nothing and no man. She is strong. She is free. She is just like Dakota North.”

Jacobson has one other characteristic that distances him from Mad Dog and the rest of the male ensemble, he’s (probably) gay. He stops by Anna’s office to congratulate her on her sketches. She says, “Oh, Luke! What a surprise! I thought you left for Fire Island!” Now, for all the reader knows Luke may indeed enjoy visiting Fire Island because he’s a pharologist in his spare time or, maybe, he’s gay. According to Thomases, Jacobson was based on “my friend, the fashion designer David Freelander, who died of AIDS in 1987. I had wanted the character to also be gay and HIV+, but Larry said that wasn’t why people read comics. I suspect that, if the series had continued, we would have gone there.” Imagine if Thomases had slipped Jacobson’s sexuality past the Marvel brass at a time when Shooter’s supposed ‘No Gays in the Marvel Universe’ policy was in effect. Dakota North was technically outside of the MU, but still, what if …

Dakota North never shrinks from a fight. Not when she’s at 35,000 feet and has to stab a hit man in an airplane lavatory, not when she’s drops another hired gun off a tall building and not when she fucks up a falcon with the busted leg of a chair she was moments before tied to. The one man Dakota can’t seem to best, despite her best, is Tony Salmons. Dakota North arrives at the advent of the Dark Age of comics, the tip of the spear, so to speak. The male gaze is an inherent vice of comics long before 1986 and Salmons is not above carrying on the tradition. Given the division of labor in comics and Thomases's lack of experience, it’s plausible to think the drawing was left to Salmons (with guidance from Hama). It’s also unlikely Thomases had the authority or agency to push back when Salmons pages came back and Amos’s backside wasn’t as prominently featured as Dakota’s.

Two pages after Salmons delivers Dakota North's thesis statement, with the opening splash page, he draws Dakota straddling a motorcycle like she’s posing for a ‘Chicks Love Choppers’ spread in Cheri. Dakota’s straddle has ‘male gaze’ written all over her body, but it’s the expression on Amos’s face in the two close ups that sells the panel of Dakota spread eagle. It’s a nod-nod, wink-wink from Amos (and Salmons) to the reader to be complicit in the moment. Also once you see Salmons has drawn Amos’s head in the bottom left panel in the outline of a penis, you can’t un-see it. Salmons’s devotees would probably say, ‘yes, he’s that brilliant of a cartoonist’ and planned it all as a joke. O.K., maybe so, but brilliance doesn’t excuse blatant sexism.

Contrast those panels with the last panel on the previous page. Dakota’s shown her acumen with a firearm. She's foregrounded in following panel, her long legs dominate the frame as she ejects the spent clip from her weapon—she’s made her point, she’s done with all this. Dakota is such a big presence, in the moment (and the narrative), she dwarfs Amos, check that, she's a colossus, she towers over him and that's just her legs, to say nothing of the rest of her body. It’s a statement of power, of who is in charge. It’s a potent use of perspective that ends on a vanishing point of the motorcycle and (hat tip to Salmons) the exit sign with an arrow pointing to the edge of the page; which readers will turn and realize any power Salmons gives Dakota he takes away when she gets on that motorcycle. Salmons’s compositions do improve over the course of the series and more often than not he draws Dakota leading from the front instead of from behind. Think what Dakota North might have been if the artist Hama had suggested to Thomases for their Fumetti comic, Mary Wilshire, had been put in charge.

***

In its flaws and its triumphs, Dakota North is playful to a fault. Its silliness is serious. At some point a joke is no longer funny if it’s real. Yes, an accounting of female action heroes in Comics History would be helpful to place Dakota North in context, but it’s not a reach to say that's a short list. It’s not clear why Dakota North was cancelled. Thomases says, “It is my understanding (which may not be true) that Jim Shooter had to cut costs, and didn’t want to cut back on the New Universe, which was his baby. I remember (perhaps incorrectly) that [Dakota North #1] sold 120,000 copies (this was back when there were newsstand sales as well). I don’t remember how much the later issues dropped off.” Salmons has a similar take, “In those days, direct sales were just coming in and were only partial of the circulation. The numbers on a book were not in from retail and rack sales, the most important then, for 12 months. We did 5 issues which is just 10 months short of the numbers coming in and Dakota was canceled because they were trimming the line to make circulation sexier as Marvel itself went on sale. That's the word I had on it.”

More mysterious than its cancellation, perhaps, is Marvel's decision to republish the Dakota North series in 2018. What are the sales metrics of republishing five issues of a nearly forgotten series and a handful of other issues featuring a not-so cult character? IPs need a refresh and there is the MCU juggernaut that waits off stage ready to snap up any and every character it already owns—the mouse gotta’ eat.

Perhaps the world is ready for, as Luke Jacobson says, a woman who “fears nothing and no man … strong … free … like Dakota North.” Perhaps it’s because Dakota North matters.