Some frustrations are universal. Banging your head against a wall means banging your head against a wall, even if beyond that wall you’ll find various supernatural entities. These are the circumstances of Emily Zegas, 25, and her 30-year-old brother, Boston. They live together in their late parents’ house, with a sprawling metropolis not far away. Both places are sites of growing pains and weird occurrences. Michel Fiffe originally published Zegas as a single-creator anthology from 2009 to 2012. Fantagraphics’ recent collection covers the Emily and Boston stories from that run, a series of thoughtful, inventive comics about camaraderie—or even codependence—between siblings and the process of making a life for yourself.

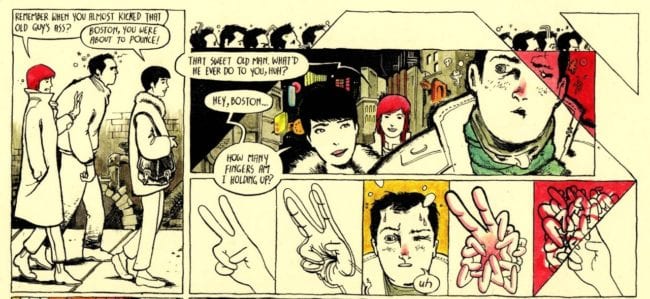

Emily and Boston have familiar dilemmas—heartbreak, job hunts—but experience moments of the fantastic on the regular. Ortega, their local “Street Mayor,” materializes out of nothingness and checks the siblings’ IDs with his floating head. Emily tackles a thief by the coat, and a skinless mass of heads and organs shoots out of the coat’s collar. The siblings treat these moments with ambivalence; when the weird appears, it’s more of an inconvenience than a revelation. The comics don’t necessarily reward an urge to understand the setting of Zegas either. Fiffe does most of his world-building by way of allusion, privileging the feeling of living in the place.

The Zegas siblings' story is a story postponed, by the way. In 2012 Fiffe deferred work on the comics in order to focus on his superteam series, Copra. So asking what purpose Zegas’s fantastical trappings serve feels at once necessary and a little unfair. It may be that the weirder elements of Zegas would have had (or will have) more plot-level influence in future installments. (Fiffe also encourages speculation about the death of the siblings’ parents and the end of Boston’s last serious relationship.) As the series stands, the weird elements at least provide grace notes to the characters’ early-adulthood blues. Emily and Boston have nominally entered grown-up life, but neither of them is in a place of real security or contentment. And their predicament is even more vivid against Zegas’s backdrop of heightened possibility, uncertainty, and risk.

Although Fiffe created Emily and Boston Zegas before he began drawing Copra, many readers grabbing the collection will have read Copra first. And while comparison can be the lowest form of criticism, in this case, both works benefit. Zegas doesn’t have action of the same frequency and intensity as Copra, but it features more humor, more heart, and more body horror—sometimes all at once. Zegas’s earliest dose of the weird involves a sickly looking, multi-limbed living wishing well, the nipple of which opens up to receive coins. In the collection’s second story, Boston attempts to replace a potted cactus. What he receives is something else entirely, with viscera to spare. But the un-cactus’s Cronenbergian motions aren’t sinister. Rather, they’re a step toward the end of a cosmic love story, with Boston and Emily as side players.

Although Fiffe created Emily and Boston Zegas before he began drawing Copra, many readers grabbing the collection will have read Copra first. And while comparison can be the lowest form of criticism, in this case, both works benefit. Zegas doesn’t have action of the same frequency and intensity as Copra, but it features more humor, more heart, and more body horror—sometimes all at once. Zegas’s earliest dose of the weird involves a sickly looking, multi-limbed living wishing well, the nipple of which opens up to receive coins. In the collection’s second story, Boston attempts to replace a potted cactus. What he receives is something else entirely, with viscera to spare. But the un-cactus’s Cronenbergian motions aren’t sinister. Rather, they’re a step toward the end of a cosmic love story, with Boston and Emily as side players.

Fight scenes are rare in Zegas—well, at least compared to Copra—but the relative shortage of them puts other visual storytelling challenges on display. At the risk of hyperbole, few working cartoonists appear to contain and synthesize as much of comics as Michel Fiffe. His pages variously evoke Ditko, Herriman, Otomo, Tardi, Steinberg, and others. Some of these resemblances might be influence borne out. In other cases, the pages might just be demonstrating a similar fluency with the language of comics. Either way, Fiffe’s layouts are alive to the moments they contain.

In the collection’s first story, Boston’s wooziness after a night of birthday drinks manifests as a series of divided panels and overlaid images, and the piece’s closing page uses negative space to convey the uneasy stillness of the morning after. In a later piece, Fiffe varies his approach for parallel stories in which Emily goes out for a job interview and Boston follows a friend to a nightclub. The spacing and pacing of the Emily sections is more deliberate, per the more mannered—and fraught—nature of the situation, and a dominant shade of purple separates Emily and her prospective boss. The Boston sections, meanwhile, are saturated with a variety of colors, which then explode across the page when a DJ takes the stage, overpowering Fiffe’s linework until it disappears. In a story following that, a spread sees Boston and his sorta-girlfriend grabbing drinks, scaling a fire escape, and cuddling on a rooftop. The sequence includes a lot at once of what makes Zegas work. Fiffe moves through mid-range, zoomed-out, and close-up panels, balancing action and intimacy as well as color and negative space.

Boston’s struggles with love and Emily’s need for a vocation feature not just in these pages but throughout Zegas. Through Emily’s job struggles, the comics attempt to find the difference between common sense and compromise—not an easy thing. And Fiffe takes a chance with his treatment of Boston, revealing a figure who’s not just adorably morose but genuinely damaged. If the collection disappoints in any way, it’s in how far away resolution seems by book’s end.

Zegas concludes not with fruitful ambiguity but more with the impression that we’re still near to the beginning of these characters’ arcs. Again, this largely the result of circumstance. But it’s also the most salient difference between Zegas page by page (or issue by issue) and Zegas as a volume of collected works. Fiffe's comics keep their world-building to a minimum and develops their characters slowly, trusting readers to orient themselves. And yet Zegas-the-book might have better served its readers and the work itself by creating more context for its contents.

The production design on Zegas is excellent, the paper stock smooth and sturdy; the collection is a lovely art object. But it presents as a discrete read to a questionable degree. The book’s copyright page does mention the work included first appeared as individual issues. The book also includes the original covers, with numbering removed, as chapter dividers-slash-interstitial pieces. But it lacks many courtesies to readers coming to Zegas from Copra or readers assuming that the series has been collected because it has concluded. A note from Fiffe or editor Jason T. Miles about the comics’ publication history, “volume one” labeling or something like it—there are a number of possibilities, and Zegas-the-book would have been a better work of curation as a result.

If the closing pages of Zegas leave readers wanting more, of course, it’s also to do with how dynamic the stories are individually, how carefully Fiffe has crafted these characters and these scenes. Zegas provides a space of endless potential for Emily and Boston, with certain challenges involved. What it does for readers is not so different. And whenever Fiffe—now an even more developed storyteller—returns to the siblings, it will be worth the complications and worth the wait.