At the beginning of This One Summer, its main character, Rose, splashes down into her bed, holding her nose and falling backwards as if leaping off a dock into the lake nearby. At the end she and a friend dig a hole in the beach big enough to contain her, and she lies in it, posing for her last picture of the summer -- this is how she wants to remember it. In between, nature, as drawn with preposterous skill by Jillian Tamaki, proves capable of enveloping her without her help. Big summer-night skies, full of stars and moonlight. Bright summer sun, hanging overhead like it will never set again. Wet, heavy summer rain, seemingly just as endless, pouring into puddles drop after drop. Trees and vines and bushes and grass and undergrowth, verdant, overripe to the point of hysteria. The lake, which is alternately drawn dominating a spread vertically like a monolith, suspending the joyous bodies of tumbling teenagers in its inviting murk, and enveloping them like a sunlit shroud when they no longer wish to be found. Against this brush-stroke backdrop stand Rose and the other impeccably cartooned characters, whose stylized simplicity (relatively speaking; no sense that these are real people is lost) when juxtaposed with those wall-of-sound environments makes them feel like inner tubes bobbing in the water, or stones tossed in it. Immersion is This One Summer's strength, and it works alarmingly well for the story that cousin-collaborators Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki are telling. It's a young-adult graphic novel, and young adults are constantly tossed into new circumstances by forces beyond their control, from puberty to parents. Out of their depth, do they sink or swim?

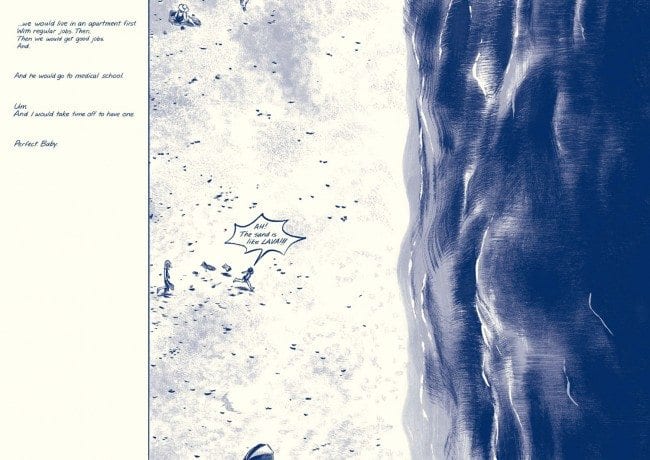

Rose is a young teenager spending the summer in the same small, rural beach town that she and her parents, garrulous Evan and tightly wound Alice, visit every year. Here she reunites with her summer friend Windy, watching horror movies and developing a stomach-churning crush on the older teen who rents them out to the pair at the town's one convenience store. An incipient scandal involving the clerk and his girlfriend forces Windy and Rose to hash out the politics of sex, which lurks just over the horizon for both of them; their small differences take on outsized importance due to the forced intimacy and intensity of summer-vacation friendships. Meanwhile, problems between Evan and Alice reach the point of low-key estrangement, with alternately harsh and cold Alice appearing to bear the lion's share of the blame. As the two storylines progress, the aptness of the setting -- which the Tamakis nail in every particular, from the totemic power of housewares seen once a year to the way the surrounding town seems both comforting because of its context and intimidating because of its unfamiliarity -- grows more and more apparent. It's a summer house, a place to which children are brought as passengers (or, less charitably, cargo) by their parents, deposited for two months, and expected to find a good time. A sequence in which Rose stares down the afternoon sun when it gets on her nerves sums it up: the sun's not going anywhere, and neither are you.

Yet to the Tamakis' great credit, the mom is not a monster. Alice is drawn far too vividly for that, for one thing. Her hair, cut to an awkward length and swept back over a high forehead, subtly suggests she has things on her mind, the kind of things that cause you to run your hand through your hair in exhaustion or exasperation. Her wiry physicality connects her to that of Rose's crush, the lanky teenage convenience-store clerk Dunc, as well as to Rose herself, and sets her apart from the burlier good-time-guy mien of her husband and brother-in-law, as well as her swirlier, curvier sister. Her John Lennon glasses easily become blank white circles, which when combined with her tendency to talk while facing away from Rose makes eye contact a fleeting connection, desperately craved. All of this is reflected in the story itself, which treats Alice's needs to have needs that aren't coterminous with her child's as understandable and valid. Parents' mere failure to anticipate and meet the emotional requirements of their children is treated as a mortal sin by far too many comics about teenagers geared toward adults, so it's deeply refreshing, and impressive, to see a comic about teens for teens treat even difficult grown-up characters with empathy and respect.

It also respects its teenage characters (to say nothing of its readers) enough to show them being jerks, and not in a rote emotional-crime-doesn't-pay way. Dunc is a convincingly joli-laid crush object, his features too big and angular by half, but the appeal of his near-adult body's sinew and sweat readily apparent, never more so than in a two-page, two-image sequence of him standing on his bike pedals, working them up and down. But his cheerful, only slightly patronizing kindness to Windy and Rose gives way to his near-unforgivable (if understandable) abandonment of his girlfriend when that relationship gets her into the usual kind of trouble. Rose, in turn, reflexively takes Dunc's side, badmouthing the girl to Windy, even concocting elaborate and obviously false stories of her cuckolding him. It takes guts to show your hero being petty without pointing to it in big neon letters.

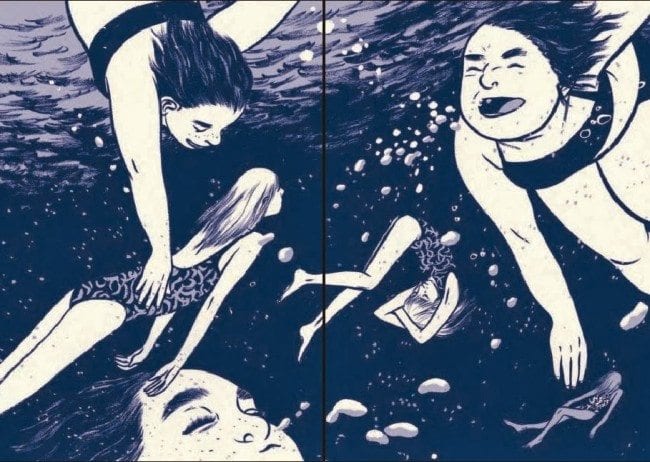

Unfortunately, that finely calibrated sense of subtlety doesn't carry all the way through. If immersion is the book's strength, then it's easy to understand why its authors would be tempted to set its climax underwater. Offshore, the two main storylines converge, as storylines are wont to do, real life less so. Either driven to suicide by or suicidally drunk because of Dunc's rejection, Jenny runs from her friends and, fully clothed, swims out too far to safely return. Rose calls for her mother, who runs full-tilt into the lake to save the girl. Two spreads tell the tale: Jenny slowly sinking, a black silhouette against what little of the water is lit by the moon; Alice's legs a white streak, disappearing into the murk to rescue her. The backstory comes out afterwards, when Rose and Windy's mothers, wrapped in blankets and sipping wine while their daughters are believed to sleep, discuss the miscarriage Alice experienced while swimming at that very beach last summer. So there's your cathartic punchline: She lost one child only to save another in the same womb-like waters. Sadly, this aggregation of symbolism, resonant reversals, and suddenly braided plot threads is piled way too high to come cooly undone under the surface, no matter how well Jillian draws what lies beneath. After a book spent shrewdly threading a series of sharp narrative curves, it's hard to blame the authors for flooring it when the finish line's in sight, but it winds up careening off-course.

But looking for some grand narrative here is superfluous to the book's pleasures, even if the book would (duh) be greatly improved if it had managed to pull one off. Throughout This One Summer, Jillian's art is like Proust's madeleine, calling to mind half-forgotten memories with real sensual power. The Tamakis' writing is often equally vivid, building a summer from sleepovers and wet bathing suits, sex talk and Friday the 13th, candy and corn on the cob, debilitating crushes and the inexorable approach of autumn. That's plenty to remember it by.