Who is Connor Willumsen? In 2009, Willumsen penciled an issue of Mike Allred’s Madman, and in 2010 he drew three covers for Dust to Dust, Boom’s prequel to their comics adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Perhaps Willumsen’s most notable contribution to genre comics, however, was his art for “Where the Devil Don’t Stay”, written by Jason Latour for Untold Tales of Punisher Max #2 (2012). Latour’s story, about a family of redneck criminals who capture the Punisher and then fall apart while arguing over what to do with him (kill him or deliver him to a crime syndicate?) is Eisnerian in its focus on disposable supporting characters instead of the marquee lead. The Punisher doesn’t speak a word in this comic, and his face is cloaked in shadow. He’s only a MacGuffin, a narrative pretext that creates homicidal dissention among the rednecks.

Latour’s nihilistic script follows noir tradition, but Willumsen’s art prompts most of the kudos from Matt Seneca in a Comics Alliance review:

This comic is cartooned, not illustrated, with the slightly creepy photo-traced gloss of the average Marvel comic stripped away like a bad paint job, realist anatomy set aside in favor of expressive posing and figure drawing that actually tells us something about who each character is. The Punisher looms black and hunched in the corners of panels, his massive, vein-popping form never fully fitting into a single frame, as his all-too-disposable nemeses scamper around the Kentucky farmhouse the whole issue’s set in, blowing each other to smithereens as their faces twist and distort like silly putty.

Seneca celebrates Willumsen’s ability to pivot his “camera” into “the heads of character after character,” plunging the reader into identification with each of the doomed hillbillies, and admires how Willumsen’s style evokes “a who’s who of the past decade’s best mainstream cartoonists” (Pope, Quitely, Baker, Kordey) while retaining its own uniqueness.

“Where the Devil Don’t Stay” ends with a freed Punisher shooting the “Fuck you, Gary” teenager in the head. Right before he dies, the kid looks around a barn littered with the corpses of his sociopathic family, and mutters, “This--this has to all mean something... it h-has to. Don’t it?” Did Willumsen re-read the previous twenty pages of his Punisher story, look at his images of men shot in the eye and tumbling lifeless into the dirt, and wonder what all this means? Did he suspect that it means nothing?

Who is Connor Willumsen? Before and while drawing his Punisher story, Willumsen made career moves unusual for genre cartoonists. He took Frank Santoro’s correspondence course, and Santoro later praised the above page from Punisher Max for retaining a powerful page center “by breaking up the grid at the bottom tier.” Willumsen also served as the 2012-13 Center for Cartoon Studies Fellow, and told James Sturm that his initial goals for his Fellowship year were modest: “I wanted to facilitate a situation where my obligations were as aimless as they ever had been, cultivate a patient boredom, and see what materialized in the vacuum.” For Willumsen, finding his aesthetic way via “patient boredom” helped him grow beyond the idea of a conventional career, into a purpose “that has no obvious practical merit,” the creation of new images of “worth” for readers hungry for new ways of seeing. Willumsen reminds me of David Mazzucchelli: both quickly mastered genre comics, and then just as quickly left behind mainstream publishers in search of Meaning and Art.

The main way Willumsen distributes his worthwhile images is through webcomics. His site has several remarkable online stories, including the Anders Nilsenesque marcofthebest (2012) and Calgary: Death Milks a Cow (2013), his Santoro course assignment, now cross-posted at the Study Group website. (Calgary’s surreal narrative, wiggly lines and slabs of bright expressionist color remind me of Rubber Blanket-era Mazzucchelli stories like “Discovering America” and “A Brief History of Civilization.”) Also on Willumsen’s tumblr are the first 55 pages of Treasure Island (2013), his CCS Fellow project and the first installment of a serial also available as a printed, oversized pamphlet from Breakdown Press.

Before we look closely at Treasure Island, you should read the online version--and send some pocket change to Willumsen (there’s a request for donations at the bottom of each “page” of his online strips) or order the print comic from Breakdown.

Treasure Island begins conventionally: the opening seven pages introduce the setting and the characters. First is a vast green rain forest and a “research institute,” all drawn in green lines against a lime background, the green hues and borderless panels emphasizing the ubiquity and expanse of the jungle. The images of Dr. Joy researching plants, lifting weights, and gardening in the heat define her as intelligent, hard-working and strong. (Note her physical strength in the splash where she is posed with her walking stick: Willumsen gives her the heavy crosshatching and thick legs of a Crumbian, Nubian force-of-nature.) In contrast, Doug Irving Ray is a less driven, more pleasure-oriented personality who finds time to read in the grass, sleep in a hammock, and do Yoga. (Ray may be a different Crumbian type, the lazy hippie.) The dog’s two names reinforce what we already know of the characters. “Krisp” is the kind of snappy name Dr. Joy would give to a pet, while “Dutchy” may refer to the pot that Doug smokes frequently throughout the story. Krisp/Dutchy eats, shits, sleeps, and does typical dog stuff, though he also wears a dunce cap (belying his status as a “smart dog”?), a hat that prefigures the floppy sleeping cap worn by another animal, the foul (fowl?)-mouthed duck that dominates the finale of Treasure Island’s first chapter.

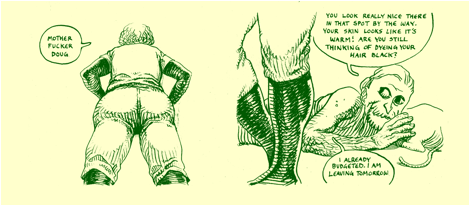

After presenting his exposition, Willumsen establishes a problem for his characters to overcome: Dr. Joy’s plans to leave the institute are scuttled by their need to raise money and buy replacement parts for their satellite dish. Subsidiary obstacles are brought in, such as Maxwel, the bureaucrat who speaks in laughably pompous rhetoric (“...to provide you with a facility wherein you may perform with autonomy and pride your duty…”) when he refuses to give the researchers extra cash, but more interesting are the small interactions that demonstrate intimacy between Doug and Dr. Joy. When Dr. Joy realizes that her trip will be delayed, Willumsen draws her body from a low angle, her reaction impossible to read because her face is turned away from us. Doug tries to diffuse the tension with insincere, playful flattery:

Doug’s comments about Dr. Joy’s “warm skin” are just banter between friends. Later in the story, Doug tearfully confesses to missing a man named Devon, who is on an “internship in the Antarctic,” and it is clear that Doug is gay and in a rocky long-distance relationship with Devon. Dr. Joy and Doug are close, though, comfortable enough to wrestle together to burn off their frustrations (the Amazonian Dr. Joy wins), and they follow their wrestling match with wine, a nice dinner, and intimate talk under the stars.

There are odd moments in the first half of Treasure Island, particularly Doug’s poetic reaction to the Milky Way (“Swath of ecstacy [sp], of experience!”), but it’s in the latter half that Willumsen really begins to subvert his own relatively conventional storytelling. While watching Independence Day (1995) and discussing the inevitability of death with Doug, Dr. Joy has a sudden, overwhelming reverie (or perhaps an out-of-body experience), represented by her disembodied head floating above green panel backgrounds. She thinks in fragments that don’t cohere, yet hint at some past trauma involving a gun (“The hell are you doing?” / “I’m just borrowing it” / “Do you really want to shoot me?”), and her pain is intercut with instances of death outside of her head: Doug’s swatting of an insect (that Krisp then eats), and the death of Independence Day’s First Lady. Although she’d previously turned down Doug’s pot, Dr. Joy smokes some now, and then retires to her bedroom, where she receives a guilt-laden e-mail from her brother Gary about missing a Skype call with their ailing mother. Much of this serves a narrative purpose—Willumsen simultaneously sets up backstory and future conflicts for Dr. Joy--but the abrupt appearance of her head in the void is a stylistic flourish that, like Jimmy Stewart’s flying head in Vertigo (1958), wrenches us out of naturalistic storytelling.

Alone in his own bedroom, Doug also gets bad news on his computer. Nervous, he writes a seemingly breezy e-mail to Devon, and while scrolling through the photos on Devon’s Facebook account he stumbles across images of his boyfriend with another man. Immediately after Doug’s discovery (“What the Hell”), we turn the page (at least in the print version of Treasure Island) and see this:

Is the shadow-hidden creature on this page a metaphor for Doug’s jealousy? (And is it just one creature?) The recto of this spread is a splash page of a field of stars, a call back to Doug’s poem about the Milky Way, a poem whose line “a grand solitude” is an apt description of Doug’s state of mind after Devon’s perceived betrayal. But stars also appear when Krisp/Dutchy howls at “Canis Major,” and when Dr. Joy decides to watch Independence Day rather than talk with her mother. What do these stars represent? Do they put problems with families and boyfriends into perspective, or do Dr. Joy and Doug feel as if their problems are as insurmountable as the night sky?

After the starscape comes Willumsen’s most audacious move: a bizarre six-page performance by “a raving mad down dirty duck” that smashes the rules of Treasure Island’s narration. This sequence comes out of nowhere; Willumsen withholds any clear explanation (such as Dr. Joy or Doug sleeping) that defines the duck as a dream. Further, Willumsen’s three-dimensional visual world is replaced in the final pages by a flat, amateurish silhouette of a cityscape, against which the humanoid duck hops, dances, quacks, and shoots his gun at an unseen audience while yelling “Fuck you!” This bizarre scene ends with a series of close-ups on the duck’s crotch as an erection springs out from between his legs, a boner with the words “Thurs. / Noon EST / Bring $” written on it.

Who is Connor Willumsen? Is he a skilled, naturalistic alt-comix storyteller, or a fuck-up who ruined his story by arbitrarily putting a duck’s boner into Treasure Island’s first chapter? Or maybe he improved Treasure Island by gearshifting so radically? In his hunt for Meaning and Art, maybe Willumsen discovered (and wanted to emulate) images and stories of worth that are promiscuous, sloppy, polyphonic, and infuriating, those works that undermine the divisions between genre and sui generis, mainstream and experimental, narrative and non-narrative, even sense and non-sense. (My perennial example of such a definition-defying artist is director Jean-Luc Godard, whose films usually have “plots” and “characters,” but whose fictional worlds are porous and unstable, punctured by authorial asides and undigested digressions, by pseudo-documentary inserts, direct addresses to the camera, and text that suddenly appears on the screen.) I liked the first three-fourths of Treasure Island, but I love the duck as I love another comics character whose appearances were narratively random but unabashedly awesome: the Elf-with-a-Gun from Steve Gerber’s Defenders run. I hope that Willumsen doesn’t “explain away” the duck’s presence, even while he introduces other mysteries in future chapters.

Besides the duck, there’s other reasons to read Treasure Island, especially in its paper form. Visually, my favorite sequence is when Dr. Joy and Doug sit in the dark, watching Independence Day on a dim laptop, because the stark contrast between light and dark allows Willumsen to combine crosshatching with white outlines as halos around forms to delineate staging in depth:

The first image above is from the printed comic, the second from Willumsen’s website. Because of Willumsen’s and Breakdown Press’ printing choices, the “darks” are a saturated green here, giving the printed copy of Treasure Island a washed-out, silk-screened (actually Risographed) look that I find prettier than the uniform colors of the online version. But either or both are worth reading. Chapter One of Treasure Island was posted and published in 2013, and while finishing this review I noted that Breakdown Press now has Treasure Island #2 for sale: I’ll be returning to Willumsen’s lush, soap-operatic, enigmatic, and profane world soon. Solving the mystery is never as interesting as the mystery itself. “This--this has to all mean something...it h-has to. Don’t it?”

Does it?