The 7 Deadly Sins is a two-fisted tale full of crosses, double-crosses and enough blood to surf from San Antonio to the Gulf. Set between Texas and Comanche land (Comancheria) in 1867, The 7 Deadly Sins sets a septet of bad hombres and las mujeres on a suicide mission to return a child stolen from her Indigenous family by a fanatical priest, Father Threadgill—a revisionist twist on The Searchers. If this suicide squad delivers the child, they’ll be rewarded with $10,000 each by Antonio, a guilt-ridden man of the cloth who’s been skimming off Threadgill’s ill-gotten largesse. There’s killing, kidnapping in the name of Christ, scalping and blunt force trauma from hatchets, cannonballs and a rock the size of a Thanksgiving turkey.

Pulpy and action packed, the artwork by cartoonist Artyom Trakhanov and colorist Giulia Brusco starts The 7 Deadly Sins at cult status—the kind of comic that finds its way to you when you’re chasing a new fix and need to get well. Where this doper’s dream evaporates into something less so is when the slightest interrogation is applied to the writing. Drippy and stylized artwork can hide a multitude of trespasses that slough off to reveal the vaulting ambition of writer (and co-publisher at TKO Studios) Tze Chun to be dark, intense and edgy. He wants to be as cynical as Peckinpah, as indulgent as Tarantino and as righteous as Cormac McCarthy. He falls far short of such lofty goals.

The 7 Deadly Sins is Chun’s first solo writing credit for comics. He’s also listed as the co-writer, along with Mike Weiss, on another in the initial slate of releases from TKO Studios, The Fearsome Doctor Fang. Before writing and co-publishing comics, Chun worked as a TV and film writer, director and producer (Gotham, Once Upon a Time). Perhaps writing comics gives Chun occasion to indulge in violence and the ill treatment of Indigenous people that can’t be found in milquetoast mainstream television.

As pointless and facile as The 7 Deadly Sins fares, at times, in its themes and plot, credit Chun with an idea that crackles with an incendiary spirit that Trakhanov and Brusco can pick up on and run with. The art of The 7 Deadly Sins provides personality and a veritas that Chun covets, but does not achieve in his writing. If bad parents, an airless portrayal of Indigenous people and a hazy point of view don’t put you off your meal, what’s the harm in indulging in some empty calories, especially when it looks this good?

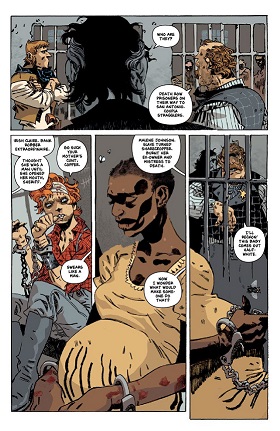

For all his bald striving, Chun creates memorable characters. So what if he cobbles their looks and personalities from stolid tropes and sources he clearly adores; imitation being the sincerest form of flattery. Chief among Chun’s creations is Jericho Marsh, an escaped slave and ex-Union Army officer who led an alliteratively named badass bunch, “Marsh’s Marauders,” on missions best described as black ops and morally gray. Marsh is the hub on which the plot and an overstuffed cast spins. He’s a simulacrum of Samuel L. Jackson’s Major Marquis Warren from The Hateful Eight, who himself, of course, is a character drawn from other wells of pop culture ephemera. Like his progenitor, Marsh’s intelligence, morbidity and charisma carries the weight of the narrative. All he wants is to rescue his daughters or the twin girls he thinks are his daughters from a life and a system servitude on the plantation. The details surrounding these children may be convoluted, but not Marsh’s intent to rescue them, be they of his blood or not. Noble, no?

Trakhanov’s design for Marsh is all hard cuts, angles and deep gouges. A man made for  privation and endurance. His sole affectation is a nest of hair piled high on the right side of his head. It perches over Marsh’s right eye, foppish to a fault and daring any interlocutor to ask why such a tough S.O.B rocks a dandy’s conk—a Byronic hero’s Byronic hero. Astride a horse wearing his Union blues and white cavalry gauntlets or pistol whipping a woman or killing a prisoner, Trakhanov makes Marsh look cool, always and untroubled by his transgressions, past or present.

privation and endurance. His sole affectation is a nest of hair piled high on the right side of his head. It perches over Marsh’s right eye, foppish to a fault and daring any interlocutor to ask why such a tough S.O.B rocks a dandy’s conk—a Byronic hero’s Byronic hero. Astride a horse wearing his Union blues and white cavalry gauntlets or pistol whipping a woman or killing a prisoner, Trakhanov makes Marsh look cool, always and untroubled by his transgressions, past or present.

Either by possibility or providence Jericho Marsh mirrors the other African American character in The 7 Deadly Sins, Malene Johnson, in more than their initials. The toughness and earned vengeance they share is expected, except where Jericho survives and succeeds, Malene suffers and sacrifices. Malene finds herself in the ‘family way’ thanks to a clueless, slave owner with a heart of gold, Ethan, his family’s scion. As told in flashbacks of high contrasted shades of green, thanks to Brusco who dusts off her Scalped color palette throughout, Malene’s life on the plantation is more Arcadian idyll than Hellish toil. Born a slave, Malene is free when she and Ethan consummate their childhood passions, which conveniently keeps this action off-stage. From Ethan’s reaction to the pregnancy and his willingness to set Malene up in a house near the plantation, he appears more romantic than a rapist. The power dynamic says different. She declines to play house and escape. Before she can shuffle off that plantation life, Ethan’s daddy attacks her and accuses her of leading his son on with her “advances.” In the fracas, an oil lamp crashes to the floor, which sets Malene’s attacker, his wife and the plantation house afire. Yet, Malene doesn’t need a tragic backstory to garner sympathy or agency. She is a black woman living in the south during Reconstruction. She's also pregnant and on the run for killing white people. The scale doesn't need any help.

As The 7 Deadly Sins unfolds its rogues gallery—all of whom, including a transgender bank robber, Irish Claire, receive cursory backstories—Malene’s belly distends beyond the panel gutters as she slumps, shackled alongside the other prisoners. Her pregnancy distracts from her baldness, almost. Trakhanov adds little tufts of hair poking through her scalp, a detail showing she cut her own hair while on the run. Her knife skills are evident whenever there’s killing to be done. Trakhanov delights in drawing blood gushing out of heads or pouring from limbs in ropey maroon curlicues where and when Malene’s blade or any flying projectile finds purchase. When he’s not globing up the page with gore, Trakhanov drowns it in ink, as is his want. He chooses to forgo Marsh’s rough-hewn aspect and instead hollows out Malene’s face and neck with shadowy recesses of refusal and desperation. Trakhanov rarely textures her face with crosshatching; the darkness is always brushed in and thick. This subtle change in technique to show how these two characters have different personalities, different fates, perhaps, demonstrates how Trakhanov’s talents elevate the material he’s been given.

As The 7 Deadly Sins unfolds its rogues gallery—all of whom, including a transgender bank robber, Irish Claire, receive cursory backstories—Malene’s belly distends beyond the panel gutters as she slumps, shackled alongside the other prisoners. Her pregnancy distracts from her baldness, almost. Trakhanov adds little tufts of hair poking through her scalp, a detail showing she cut her own hair while on the run. Her knife skills are evident whenever there’s killing to be done. Trakhanov delights in drawing blood gushing out of heads or pouring from limbs in ropey maroon curlicues where and when Malene’s blade or any flying projectile finds purchase. When he’s not globing up the page with gore, Trakhanov drowns it in ink, as is his want. He chooses to forgo Marsh’s rough-hewn aspect and instead hollows out Malene’s face and neck with shadowy recesses of refusal and desperation. Trakhanov rarely textures her face with crosshatching; the darkness is always brushed in and thick. This subtle change in technique to show how these two characters have different personalities, different fates, perhaps, demonstrates how Trakhanov’s talents elevate the material he’s been given.

For all her Grace Jones chic, Malene is doomed, literally cast to carry her own ruin. No amount of pride, sass and agency can counter the fact she’s a pregnant black woman on the run in Texas in 1867. She’s already on a suicide mission before she takes the gig. Her pregnancy would be clever on Chun’s part if it didn’t feel so manipulative and disturbing. Unlike the capacity for revenge and redemption afforded Jericho, despite racial barriers, Malene remains hamstrung due to her gender and physical condition. She’s sacrificial from the jump—a plot device dressed as a character used to sow sympathy only to be cast off and cut out for the sake of drama and the demands of the narrative.

Because the good guys (and girls) are the supposed baddies in The 7 Deadly Sins the story’s villains, Father Threadgill, a crooked sheriff and a raft of reprobate Texas Rangers, play as cartoonish stock characters. After he kills their parents with the help of the rangers, Threadgill ‘rescues’ indigenous children in order to populate his orphanage and civilize and sanctify, as he put it, “the barbaric plains.” At least Threadgill and his goons have morality, corrupt as it may be. The Indigenous, on the other hand, are presented as only bloodthirsty killers and automatons of vengeance. Chun leaves no doubt that Threadgill et al. are the real sinners, but does little to put a face on any Indigenous person that isn’t obscured by blood, viscera and an unwillingness to choose beyond violence.

Because the good guys (and girls) are the supposed baddies in The 7 Deadly Sins the story’s villains, Father Threadgill, a crooked sheriff and a raft of reprobate Texas Rangers, play as cartoonish stock characters. After he kills their parents with the help of the rangers, Threadgill ‘rescues’ indigenous children in order to populate his orphanage and civilize and sanctify, as he put it, “the barbaric plains.” At least Threadgill and his goons have morality, corrupt as it may be. The Indigenous, on the other hand, are presented as only bloodthirsty killers and automatons of vengeance. Chun leaves no doubt that Threadgill et al. are the real sinners, but does little to put a face on any Indigenous person that isn’t obscured by blood, viscera and an unwillingness to choose beyond violence.

When TKO Studios launched in late 2018, its distribution model (and not the comics) led the press coverage, despite marquee names like Ennis, Epting, McDaid, Breitweiser and Ponticelli. TKO is hand selling for the digital age (ShortBox, but with more hands and presumably more money), a direct sales approach to readers and retailers that eschews Diamond’s distribution stranglehold. In addition to digital downloads, the comics are sold as singles in a traycase or (slightly) oversized trade paperbacks. The intent is a feeling of punk, and an illusion of direct market concern. In New York Times write-up, Chun says, “We are not opposed to our comics being adapted. Anything that drives people to the medium is great.” Chun ends by saying the guiding (and rhetorical) principle of TKO is, “What’s best for readers?” One could argue what’s best for readers is books and not movie or TV adaptations. As snotty and old-fashioned as that sounds, it’s accurate. It’s tempting to read Chun’s statement regarding the comics he co-publishes and not think an adaptation of The 7 Deadly Sins might work better on the screen. Or to go further and question if that’s been Chun’s game all along: comics as conduit to film and television adaptations. Chun’s background and industry connections would say as much.