There's a line I've always remembered from a minicomics review in the great '80s underground anthology Weirdo: "Spill some ink." I find it a handy little reminder/admonishment to plumb the depths in my own comics, to be as honest as possible. And I’ve thought of the phrase many times when reading work I found banal, emotionally dishonest, or simply unclear in intent. Spilling Ink: “Dig Deeper or Don't Bother.”

Spilling ink appears to come naturally to Gabby Schulz (also known as Ken Dahl). In his writing and art, Schulz offers brutally frank self-assessment worthy of R. Crumb at his most lacerating; grim, grotesque imagery that often metastasizes into Cronenberg-esque body horror, and scathing outrage toward American societal inequities that any hardcore anarchist or hard-left political cartoonist would appreciate. In Sick, Schulz doesn’t just spill ink, he spills blood and guts: bright, red & squishy, in operatically grotesque, often nightmarish drawings. He depicts the title illness in full-scale body-horror mode, which in turn triggers an intensely self-loathing self-examination, which in turn bleeds into a scathing indictment of the American body politic. It's a challenging 82-page primal scream, like a performance art piece—the kind Karen Finley was famous for in the '90s—in illustrated form, viscerally tearing apart all the personal and social filters we construct like armor, to keep ourselves going, to stay sane.

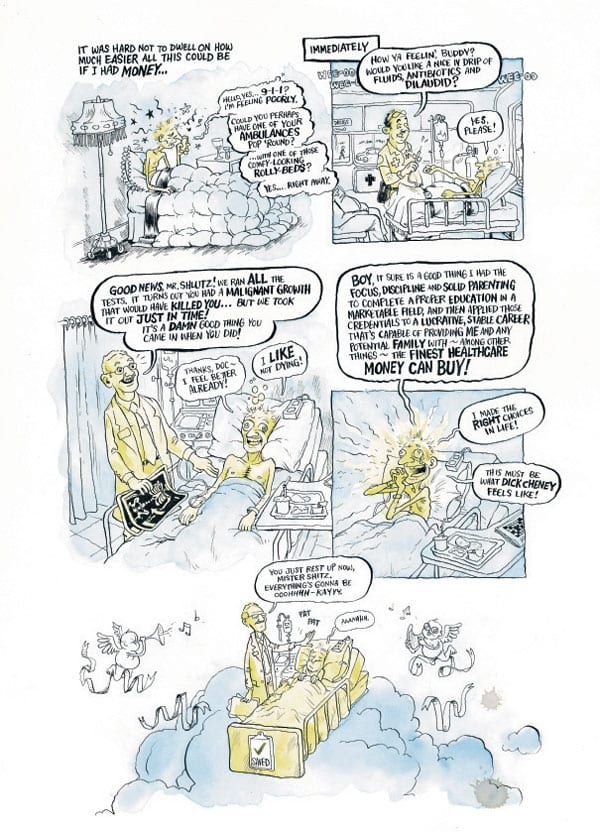

Schulz gets right down to business, opening with a vivid description of his sudden malady: "Once I got sick. Real sick. A brain-melting fever, constant liquid shits, uncontrollable shivers, horrible nightmares. A tearing pain like a giant claw was scooping out my guts [...] After a couple of nights of this," he continues, "I started to worry." From there on his narrative begins slipping in and out of reality and bitter fantasy, much like a fever dream. He first depicts a fruitless trip to the ER, where he’s treated the way anyone with no money, no health insurance, and no resources can expect in our country: a contemptuous doctor hands him a block of "Extra Strength Debt" and tells him, "Come back when you've got a real problem and a real JOB." With more than a touch of black humor he envisions health care as experienced by those who can actually afford it:

Back in the sickbed of his dingy little apartment, Schulz ruminates on past regrets, his grim present, and gets full-blown existential about the state of the world. From here on, Sick is quite different in tone from Schulz’s previous works: his collection of short comics Welcome to the Dahl House (Microcosm, 2008), or his previous book with Secret Acres, the double Ignatz Award-winning Monsters (originally published in 2009 and newly released this month). Monsters, a frank, wonderfully entertaining (and quite funny) autobiographical look at the trials and tribulations of having oral herpes, presents Schulz/Dahl as an obsessive worrier, able to take a medium-level problem like herpes and blow it up to biblical proportions. The antagonist, ostensibly the (often-anthropomorphized) herpes virus, is actually Schulz himself. An intense, glass-half-empty sort of fellow, he torments himself throughout with his insecurities and seeming inability to reconcile his feelings of shame and self-loathing. Ultimately, Monsters wraps on a lighter note, with an unexpected resolution to Schulz’s health problem—and he even gets the girl in the end.

Sick offers up no such redemption, as Schulz takes us with him through his physical and mental freefall: "My whole oh-so-precious existence looked like just a soap bubble floating on a big black sea of nothing." When his illness breaks after eleven days, his spiritual malaise continues, leaving little relief.

Sick, a sucker punch of a book, will not be for everybody (“Trigger Warning” crowd, please take note). Upon my first reading I was taken aback at its unremitting bleakness. Schulz has a real talent for identifying those little pockets of dread that punctuate our days and nights, lingering over them and illustrating them with gusto. His gorgeously grotesque visuals, often framed in washes of a nauseous green with accents of raw-meat red, recall somewhat the great Ralph Steadman; while one sequence in particular—Schulz reliving a horrifying childhood nightmare—reminds me of Josh Simmons at his most merciless. Schulz captures the experience of sickness with uncomfortable accuracy: the woozy slipping in and out of consciousness, the sense of health and wellness becoming but a distant memory–and of pain and illness defining all of one's existence. Sick joins other books in the growing genre of graphic memoirs dealing with health issues, among them Ellen Forney’s Marbles, John Porcellino’s The Hospital Suite, and Jennifer Haydn’s The Story of My Tits. While those books offer stories of people who navigated through their physical and mental problems to the point of reaching new possibilities for their lives, in Sick, Schulz’s illness is the avenue that leads him to simply confirm all of his worst fears about himself and the world surrounding him: “The sickness had become me.” This is uncompromising work by a brave and powerful artist.