Trying to survive the after-effects of an encounter with sublime beauty is the madness that permeates Blutch’s Peplum. The question of how to negotiate desire in the face of the thing which destroys all other desires; how to live after seeing death--this is the panic that terrifies Peplum’s central protagonist.

Peplum starts at the far reaches of the Roman empire, following an exiled squad of adventurers descending into a cave to find a goddess rumored to be imprisoned there. Finding her neither alive nor dead, they remove her from the cave, and are immediately cursed with the cravenness her visage induces in them. One dies of fever. Another finds his face eaten away by strange pustules. Madness overtakes the group, and in the end a lone figure stands atop a blood pile of murderous death. This man, goddess in tow, and bearing a resemblance to Martin Potter from Fellini’s Satyricon (1969), proceeds to go on a series of adventures throughout Ancient Rome that remix and refigure Petronius’ original work.

The effect is as alien as the original text, but in many ways much more brutal and violent. If Fellini’s adaption used the romantic cocksmanship at the heart of the original novel to depict a dreamlike bacchanalia of science fiction-like excess, Blutch blunts those ambitions into wild-eyed madness, interrogating the crippling obsession that the sublime experience induces within its possessed. If Fellini is the ecstasy of the high, Blutch’s Peplum is the hunger of purgatory. Ravenous, Blutch’s Encolpius loses his name to the Roman knight he murders. He becomes Publius Cimber, and vanishes into spiraling cycles of obsession and punished infidelities.

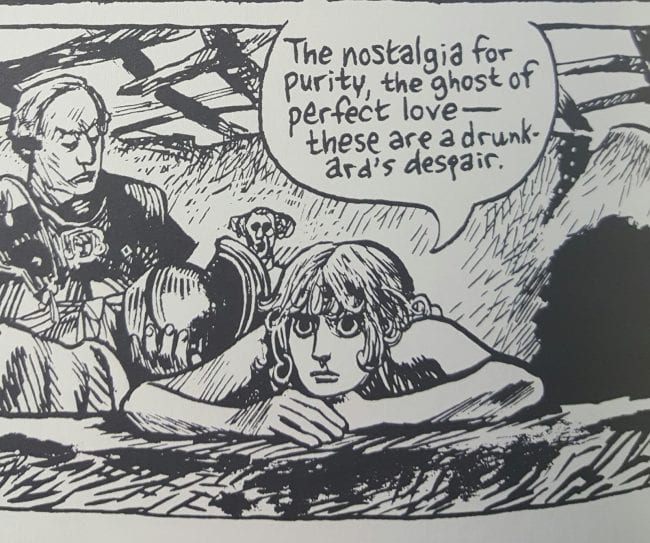

As Blutch’s Giton says about this snakeskin-fiend version of Encolpius: “The nostalgia for purity, the ghost of perfect love—these are a drunkard’s despair.” This existential despair in the face of sublime confrontation with the divine is the baseline mast that Peplum binds itself to.

One of the notable things about Blutch, which is also evident in his book So Long, Silver Screen, is that his compositions are suffused with a textural psychological expressiveness that borders on the feral. His figures carry with them a mad interiority that makes their violence intensely explicable. In the panel below, Publius Cimber has strayed from his ice goddess, renouncing her to the actress whom he has just met; and for his troubles he has been rendered impotent. In a society where, more than anything, the ability to penetrate another denotes the sacrosanct value of the masculine member, his devastation is mortal. The violent foregrounding of the actress and her alarm at his failure to perform—her pupils shrunkenly encased within violent shadow boxes, and her hair snaking out invoking the Medusa who turns men to stone with her visage—is placed against this background figure of a man, consumed in black dry brush shadow; his expression blotted out except for the tears fleeing his face, mingling with the sweat of his failed endeavor. His limbs are made to form a empty vaginal triangle, within which Blutch bubbles his jab at this newly found male void: “Mute he remains.”

It is a panel that testifies to the power of the medium's immediacy and the potency of image balanced against the hypertextual precision of multi-contexted narrative information. With Blutch, the images are not placeholders that exist solely because you need panel B to get from A to C. Rather, each panel speaks to its own sublime ecstasy and value as an image, even as it builds upon and refracts preceding (and following) panels. He mixes the poetry and convoluted intentions of the prose writer with the ineffable inexplicableness of the image-maker—existing both within words and beyond them.

On the page below, in the first panel, Publius Cimber hovers over a man he has just killed. Publius hunches over him, devolved and swallowed by the darkness of this cave and his own mind, accusing the dead man, part of a neanderthal-like group he met earlier, of being a brute. Publius then turns away from reader and looks out of the cave as two small birds fly by. Across his back Blutch has drawn beautiful parallel brush strokes, shrouding his violent human insanity; and juxtaposed against these two violent marks are two peaceful tiny ones floating in a serene white space outside of the cave. This image reflects both Publius’ paranoid closed world that he fills up too much with self, and the serene swimming of the distant in the infinite. Publius repeats his accusation, but now it reads like a self-caption.

Blutch reverses the shot once again, and pulls us out onto a large complex of caverns where we see in this skull-knotted tapestry of early human culture, a peaceful complexity being pitted against Publius “modern” human violence. His evolved features are a product not of his ability to coexist, but of his maddening gift for violence. Again he says, “A real brute,” but now it is clear that the accusation is impotent, and ironically self-reflexive.

The baseline surreality of Blutch’s vision of Satyricon is fueled by this spell of alienated madness. Over and over, Publius makes one flawed choice after another. He rejects lovers in favor of the goddess, but sometimes he rejects the goddess in favor of lovers. His ideology, like the violence in Blutch’s comics, is scattered, panicked, and reaches out to scratch and strangle at the flesh that encases being. We are constantly assured by outside figures that in all of these transactions Publius does not suffer, because, after all, he loves another.

But Publius Cimber is all suffering. The love that he desires is beyond desire, and the desire that he loves is not love. His decisions lose him everything. We see him beaten, tortured, but we also see him beat and murder others—he is like a man flailing in an empty room with only his own eyes to scratch out. He has seen part of God’s face, and been driven mad by her. His desire within life has been completely warped, and the only way to re-integrate himself within the society of living is to abrogate his sanity to an afflicted journey through hell. When finally his goddess abandons the mortal plane and assumes her shape as abject corpse, Encolpius has been deranged into this dark strange howl of a man who answers humor with horror. If in the presence of the divine he was rendered into infantile psychopathy, in its absence he has become the demonic knowing man, suffused with the horror of living.