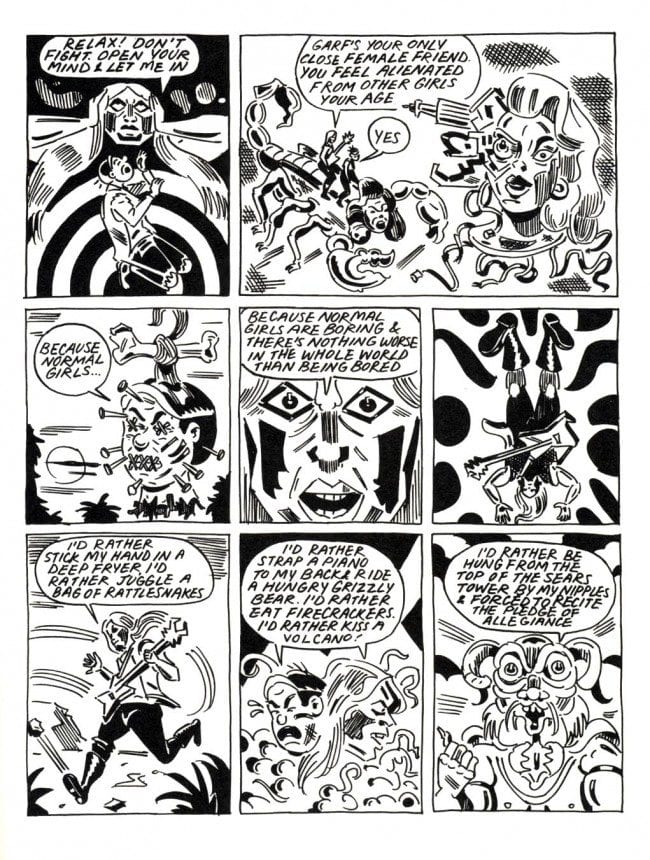

In her debut book School Spirits, Anya Davidson carries over the raw energy and power of her zines into a longer loose narrative. Following a few days in the high school lives of best friends Oola and Garf, the book is immediately remarkable for the surprisingly fluid (if sudden) transitions between ragged slice-of-life naturalism and over-the-top, surreal, metal-inspired fantasy craziness. Davidson's project here seems to be a complete demolition of rigid gender roles, as her alienated but fiercely feminist duo battle against conformity, misogyny, and boredom while also grappling with more familiar issues like identity and love.

On the page, these battles often play out in a literal sense. Oola is kind of a doom metal Walter Mitty, transforming her immediate surroundings into stream-of-consciousness fantasy sequences that are heavy on epic, visceral battle sequences and mythological vision quests. Hearing the first notes from their metal god Hrothgar at the local record store sends her into the 7th dimensional home of her hero, who attempts to aid her with her existential crisis. Seeing some relics in a museum creates the "Battle for the Atoll," wherein a brutally efficient society of women forms on an island and must fight off hordes of cruel and vicious invading men with superior firepower. Playing on themes of gender and identity, both Oola and Garf spend several pages imagining what they would be like if they were men, opening up crazy fantasies involving Hollywood, adventuring, and bedding women.

The best fantasy sequences are the hilarious one-panel takes on Oola's sexual fantasies regarding her crush on her friend Grover. These are three pages worth of tender, violent, and only vaguely erotic (in a conventional sense) acts that range from Oola as clown juggling his head to being a gondolier in Venice, languidly taking him on a romantic boat ride. There are more frank images as well, like Oola squatting and pissing in his shoes or lifting up her dress and flashing him. One senses a tremendous amount of affection and empathy from Davidson for her characters, no matter how bizarre they might be. Indeed, their quirks and kinks are part of what makes them lovable, even if Davidson finds ways to make them accountable for their actions.

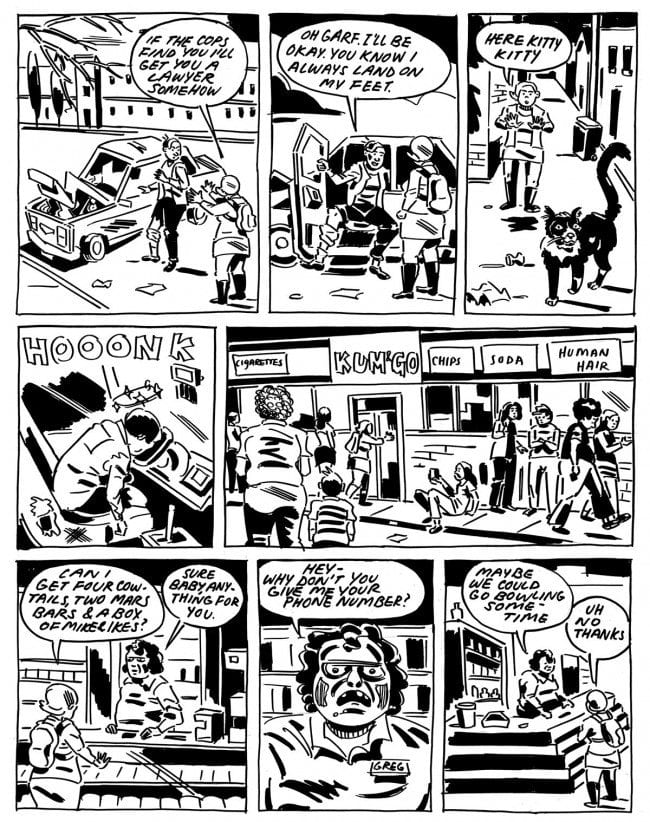

In the story that takes up the bulk of the narrative, "No Class", we enter in medias res as Oola is being chased by a cop. It's hard to pin down a lot of direct influences on Davidson's work, but her self-professed love for the likes of Milt Gross and other classic cartoonists is obvious here. The slightly ragged line creates characters who are "missing" certain connecting lines (except in some highly-charged action sequences). The lines that aren't there drive the action as much as the lines that are actually drawn on paper. The artist she reminds me most of is Steve Lafler, who uses a similarly thick line with plenty of gaps and combines balls-out trippiness with a solid, naturalistic tendency. Ted May is another touchstone, especially the high school metal stories he does that are written by Jeff Wilson. May and Davidson share the same kind of deadpan storytelling quality that treat even the most ridiculous of set-ups with deadly seriousness, heightening the impact of their stories.

"No Class" then flashes back to Oola at the beginning of her school day, as she negotiates her crush on Grover, offensive sexism, and the gauntlet that is high school. Each of her teachers takes on an oddly mythological quality. Some are monsters (and are even drawn as things like werewolves, which may or may not be related to the Halloween themes of ritual as a means to effect transformation), but each teacher is his or her own unique entity. Indeed, the seemingly cheery art teacher who snaps and flees from the school winds up having her own subplot involving an English teacher who's assigned Virginia Woolf's Orlando to the class. That book touches on some themes that Davidson explores in the book, namely the fluidity of sexual identity and how it plays out in society. Davidson's sympathy for her characters extends even to the teachers in the story, seeing them as people who have to deal with students who don't care.

Davidson refuses to let Oola off lightly throughout the book, and her more antisocial tendencies (like stealing stuff from a grocery store and stabbing a security guard) are directly confronted in her own subconscious fantasies. This all culminates in Hrothgar's concert, an astounding visual spectacle. Once again, fantasy blurs with reality as the security guards outside the venue confiscate drugs and weapons, disarming concert-goers with swords and maces. The ticket for the show is a particular kind of dead rat. When the show starts, Hrothgar's back-up band consists of hulking, twelve-foot tall naked women. Each gives "birth" to their musical instruments, pulling them out of their vaginas and playing these living guitars, drums, and bass, umbilical cords still attached. It's an outrageous, hilarious image once again portrayed in an absolutely matter-of-fact manner. The more important consequence of the show is Oola fantasizing that she's being confronted by her idol Hrothgar for being out of control, but he takes pity on her and teaches her a mindfulness trick.

Even though Oola's inner life reveals her as a vulnerable, sensitive, and even tender person who is wracked with guilt for not being a good enough person, she still projects an aura of being tough and unapproachable. At the end of the story, after she's gone through a transformative experience in her fantasy life, she shrugs off a concerned Garf. Davidson indicates that while Oola may have learned some lessons, her development and eventual maturity into a fully-centered person are far from over and far from certain. It's a nuanced portrayal of a high school girl that transcends the reductive qualities of depicting a "freak" and instead lays bare her complicated feelings, her emotional and intellectual sense of confusion and wonder, and her rich inner life. This book takes a wrecking ball to every cliched and stale portrayal of life as a teenager. There is just enough structure and organization in its narrative to keep the book from flying away on its tangential fancies, and the mix of whimsy and viciousness in those fantasies prevents a sense of dull sameness from weighing the book down. Indeed, for a book intent on exploring the chaos of one girl's life, the book is supported by a rock-solid narrative and even visual structure, as even the weirder drawings never get too psychedelic to track across the page.