The first moment -- but certainly not the last -- that made me stop reading How to Be Happy, turn back the pages, and immediately re-read them came early. "In Our Eden", the lead-off piece in Eleanor Davis's masterful new collection of short stories, concerns a back-to-nature commune driven to dissent and dissolution by its founder's purity of vision. Some members chafe at the convention by which every man is called Adam, every woman Eve. Others fall away when the leader, a towering and barrel-chested figure with a ferocious black beard like something out of a David B. comic, takes away all of their prefab tools. The rest depart when he insists they neither farm nor kill for food, literalizing and reversing the Fall's allegory of humanity's move from hunter-gatherer to agrarian societies. At last it's just this one Adam and the Eve he loves. By the next time we see them, Adam's gargantuan physique has been pared away, his ribs visible, his nose reddened for a sickly effect, demonstrating Davis's remarkable ability to wring detail and expressive power out of the simple color-block style of the piece. He comes across Eve, nude and stork-skinny, washing her long hair in a river. He goes to her, nude himself. "I'm ready for the bliss to come," he says right to us in one of the recurring panels of first-person narration that have been peppered through the comic. They embrace. "I'm ready for the weight to lift." They kiss.

The first moment -- but certainly not the last -- that made me stop reading How to Be Happy, turn back the pages, and immediately re-read them came early. "In Our Eden", the lead-off piece in Eleanor Davis's masterful new collection of short stories, concerns a back-to-nature commune driven to dissent and dissolution by its founder's purity of vision. Some members chafe at the convention by which every man is called Adam, every woman Eve. Others fall away when the leader, a towering and barrel-chested figure with a ferocious black beard like something out of a David B. comic, takes away all of their prefab tools. The rest depart when he insists they neither farm nor kill for food, literalizing and reversing the Fall's allegory of humanity's move from hunter-gatherer to agrarian societies. At last it's just this one Adam and the Eve he loves. By the next time we see them, Adam's gargantuan physique has been pared away, his ribs visible, his nose reddened for a sickly effect, demonstrating Davis's remarkable ability to wring detail and expressive power out of the simple color-block style of the piece. He comes across Eve, nude and stork-skinny, washing her long hair in a river. He goes to her, nude himself. "I'm ready for the bliss to come," he says right to us in one of the recurring panels of first-person narration that have been peppered through the comic. They embrace. "I'm ready for the weight to lift." They kiss.

I turned the page, curious as to how the story would end. Some final irony? Some subtle but biting indictment of utopian folly? A widening of the view to deny the lovers centrality in their world? None of the above: the story had already ended. The build-up I'd read into it -- a crescendo of extremism that would end with Adam's hubris exposed and exploited -- didn't exist. The easy climax, the stacked-deck scenario so common in stories about true believers in which author and audience get over at the expense of the characters when the latter are made to look foolish for foibles the former recognize instantly, never comes. The climax had come two pages before, when I turned from one page to the next and reached a splash-page image of the moment when Eve turns to see her Adam. This moment of connection is the story's resolution. The use of Adam and Eve's human bodies to communicate to one another, to seek the bliss that's coming, to lift that weight, is the image Davis wants us to leave with. No moral, no punchline, no muted epiphany -- discarded along with all the other distractions, they leave only Edenic bliss behind.

In many ways, this is also the larger story of How to Be Happy. Davis's first book for adults, it collects years of work -- the sources ranging from anthologies like Mome and Nobrow to work Davis self-published on her website -- by one of the few cartoonists about whom the back cover's "one of the finest of her generation" claim is unlikely to garner much argument to the contrary. All of that work is at least good. But it's really something to see how some of the earlier pieces pale in the light of the later material's lacerating simplicity.

"Seven Sacks" and "Stick and String", both from late-'00s Mome volumes, are lushly illustrated, melancholically mordant fairy tales. As a draftsperson Davis is already enormously accomplished. But the cute-fantasy cartooning, a very of-its-time technically advanced tweak of the Top Shelf house style, softens Davis's blows, particularly in the creature designs. The writing's easier here, too. The two protagonists -- a ferryman who looks the other way at the wriggling sacks of most-likely-human prey his monstrous passengers are toting and a wandering male musician who emotionally and sexually fascinates a dryad with his playing only to discover that this subversion of her nature will be exhausting to maintain -- make moral mistakes that all but advertise themselves in neon. "Thomas the Leader" is the most successful of the older stories. The ruined house the titular kid and his brother explore is drawn in tremendous detail and supported by thick spotted blacks -- a fascinating style, if only to recognize just how good Davis was at it and how completely she later abandoned it -- while the story's central supernatural mystery remains unsolved, and it ends on a satisfyingly unsatisfying note of cruelty.

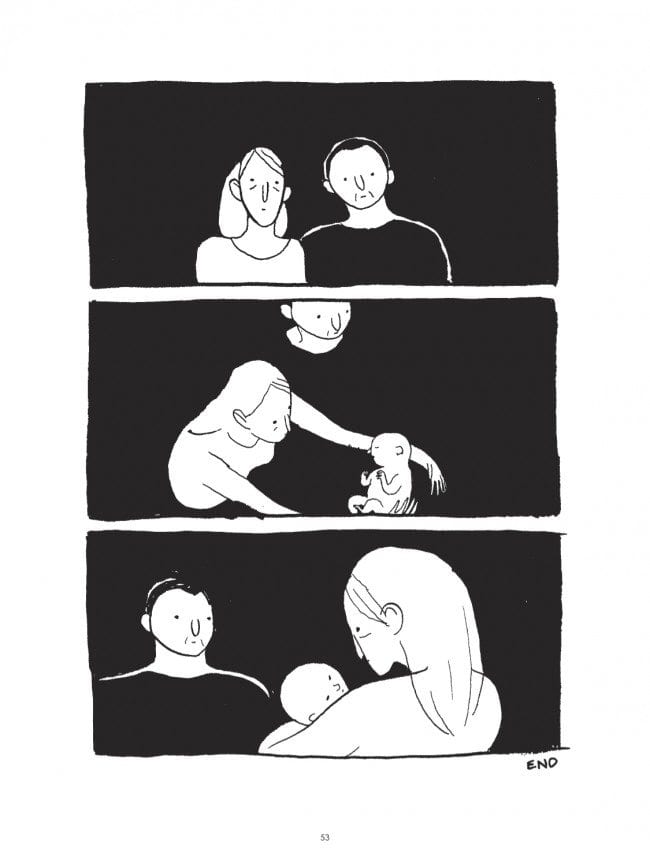

By the time we arrive at, say, the color-block work and the pencil sketch comics Davis has primarily posted online, cruelty, and humanity's attempts to cope with our embodied existences in a world so full of it, emerges as Davis's muse. With a gestural pencil line as evocative as anyone's this side of Mattotti, Davis draws a man in a t-shirt and bare feet tenderly snipping off the fingers of his reclining girlfriend, a relationship suggested in this sequence of two silent images through body language alone. Another man, while having a deep cut attended to by his own significant other, looks into the wound to see bone, and within that bone "a small mortal man he'd carefully hidden inside his own good, strong body." It's the "good, strong" that wounds here, two adjectives used where one would do, suggesting the flop-sweat stridency with which we confront evidence of our frailty. Yet another couple comes clean with one another about their lack of love, indeed their belief kindness toward other people is impossible because neither kindness nor other people can really be said to exist given how trapped we are in ourselves. Their solution? Have a baby, their puzzled embrace of which suggests will solve nothing for them and be doomed to repeat their failures for its own part. One comic is simply a narrated depiction of the process by which a friend dressed and skinned a fox they'd found dead, a roundabout method of reaching the kind of dreamlike symbolism -- the fox's muscle-clad body and its disembodied skin wind up attached at the lips like "two foxes kissing," an allegorical inversion of the Adam & Eve tale -- that reality rarely provides us.

It's worth noting that these comics, with few exceptions, are done in her more recent, looser, simpler black-and-white style, whether in pencil or ink. Davis's talents as an illustrator are formidable, even breathtaking. But that skill set, by nature a matter of pleasing an audience, can read as overripe or slickly whimsical in comics form, even in the hands of a practitioner gifted in both fields. Davis's black-and-white pieces feel meaner, more focused, and more intimate, like troubling information contained in a whisper you have to lean in to hear instead of a raised-voice conversation you're having with a friend in another room.

As a counterpoint to this borderline body horror, other comics reveal the physical self as a potential source of strength. (Which stands to reason: We're trapped inside these fucking things our whole lives, and we can't be miserable all the time, so.) A strongman delights in his prowess, using it to rescue entire crowds of people he can carry along on his enormous shoulders like a benevolent Atlas who can put down and pick up his burden at will. A page turn takes us to a spread where, for the first time, he seems bested by the strain of the enormous black-shadowed apartment building he's holding up, but by the next spread he's beaming with pride, and on the page after that he's literally laughing with delight. This sequence directly follows a two-page comic in which a woman coaches a sculptor she's commissioned into portraying not just her, but her "best self" -- a towering amazonian whose preposterous haircut matches the subject's but who's "smarter, kind of Ivy-League... but real nice, too," who's got a wicked sense of humor she doesn't use against others. Like the strongman, she winds up smiling.

But tears are the most powerful weapon in Davis's arsenal. Tears redeem a comic about a woman who seeks trendy magic-bullet cures for her depression, the condescension of the premise more or less annihilated by a full-page, color-washed drawing of the woman sobbing, head in her hands, her hair and clothing a black sea, her face a mask of anguish. Tears launch a strip in which a woman, shown in profile, experiences a series of emotions, then no emotion, then simply exists, the comic's simple-sentence captions and black color slowly washed away. Tears are the subject of the collection's climactic comic, "No Tears, No Sorrow", in which a woman who's been unable to cry for ten years and thus feels distant from personal experiences she knows should move her to sadness enters a seminar for those so afflicted. The crying coach instructs the class on miming the physical sounds and bodily movements of sobbing -- there's that connection between body and mind again -- while showing cartoon caricatures of tragic facets of modern life, from unrequited love to climate change to children dying of treatable diseases. One by one the participants learn to weep, the weight of their numbness lifted at last. When one of them finds he can't stop, since after all the tragedies they've studied are all too real, the instructor absolves him of the need to solve the world's problems, feel the world's grief, be responsible for the happiness of anyone but himself. Our protagonist, however, can't learn this lesson. We leave her sobbing uncontrollably in the aisle of a supermarket, the flow of the tears too fast and sure to stop. The three pages of the book that remain are themselves dominated by motifs of uncontrolled descent -- a comic about walking in the rain trying not to think, an illustration of a woman falling into the arms of a concerned crowd below, a late-night cab ride narrated with sentiments like, "The mind is a shitty place to live. Wouldn't it be good to be free of it?"

Yet as the Edenic opening comic indicates, How to Be Happy's title isn't a bait and switch. This would be true even in the absence of the handful of strips on the title topic that Davis sprinkles across its length -- the penciled piece in which we're advised to write a more interesting life for ourselves and make believe it's real ("Just keep writing. You have plenty of time."), the strip that expands the life-as-story idea to the impulse behind prayer and advises us to "Find the stories that help you comprehend the incomprehensible....Find the stories that make you stronger.") That final falling woman bookends the collection with the opening illustration, in which one lone woman is scrambling to save an entire crowd as they fall. It's not a happy note to end on, but it's a positive inversion of how we started.

Every story selected for inclusion in How to Be Happy -- which is by no means the sum total of Davis's work; several early Mome strips are missing, and many of her gut-punch-powerful webcomics didn't make the cut -- advances the idea that grappling with sadness and suffering is the toll that must be paid to get past them. Not that it's good, not that it's right, not that it's virtuous, nor that it's immoral or evil, nor that it's a guarantee you'll get anywhere anyway -- just that it is. That's probably tragic, but it's also inevitable. And this, perhaps, accounts for that elision of judgmental lesson-learning that read so refreshingly in that very first comic. Whether you're the emaciated Adam and Eve kissing in a river or the woman surrounded by a supermarket's succor and unable to stop sobbing, that underlying story's the same. Davis tells this tale in a wide range of styles without ever losing focus. Indeed she's refining her lens on the issue to a laser-like level accuracy and efficacy, as both writer and artist. Sad or happy, Davis is one of the greats. So is this book.