There have always been critics and creators who take the art of cartooning very seriously and apply rigorous formalistic standards to the form. For example, in a recent column, RC Harvey carefully delineates the ways in which many contemporary graphic novelists — some very well-regarded — commit the sins of telling and not showing, illustrating the text rather than working in tandem with it, and (most interestingly to me) disregarding word balloons as an integral part of the comic’s landscape. I like to dissect the style and structure of our art as much as the next person, but it’s also easy to become a slave to formal concerns.

Enter Mark Connery. His minicomic Rudy throws all that comics pedantry out the window in a cheerfully anarchic spirit. Intuitive and spontaneous rather than practiced and formalistic, his hilarious, doodled-in-a-notebook-style comics emerge triumphantly from the id. It’s no wonder the tagline “Comics and Fun” accompanied many of the original minicomics collected here. Among the other taglines are “Zooty Comics for Grog Dogs” and “Bourgeois Entertainment for Stalinist Motherfuckers.” Welcome to the world of Rudy.

I first encountered Rudy in last year’s Treasury of Mini Comics (Fantagraphics) and fell a little in love. I was surprised to discover that the minicomics dated way back to the early nineties, and delighted to hear of this forthcoming compilation, edited by noted cartoonist Marc Bell. Entire issues of Rudy (usually 8-page minis) are included here, along with contributions to anthologies like Radioactive Comics, as well as one-offs, poster art, unpublished drawings, and other ephemera. The introduction by Samuel Andreyev gives the uninitiated a welcome, informative background on the comic and its creator, and the index is also helpful. (Creators and publishers, please take heed: indexes and annotations provide invaluable context and history, especially for work originally self-published.) Connery, a Torontonian, has been producing his minis and comics himself, distributing them through the mail or anonymously dropping copies at punk shows, libraries, and on public transit, leaving a portion of his readership up to the vagaries of fate. Very punk indeed.

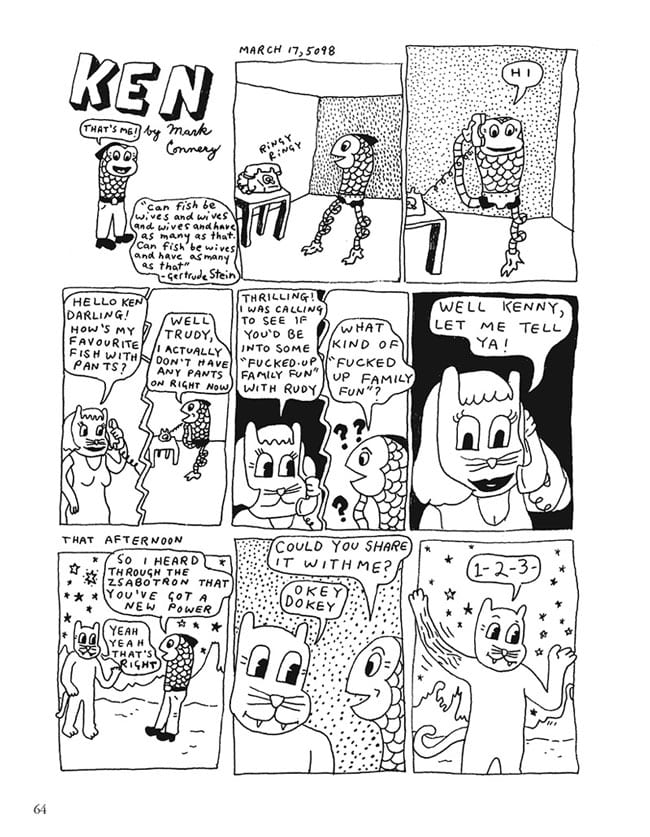

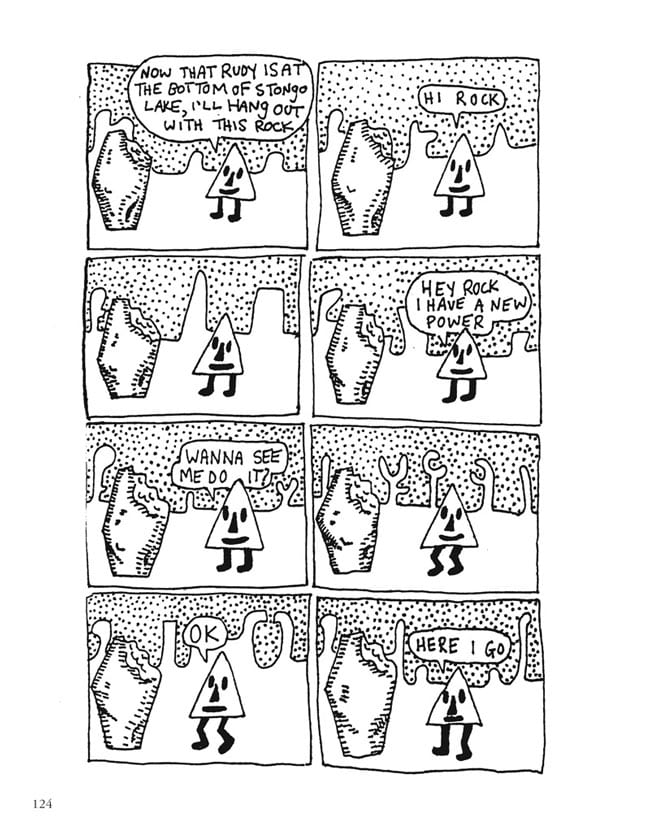

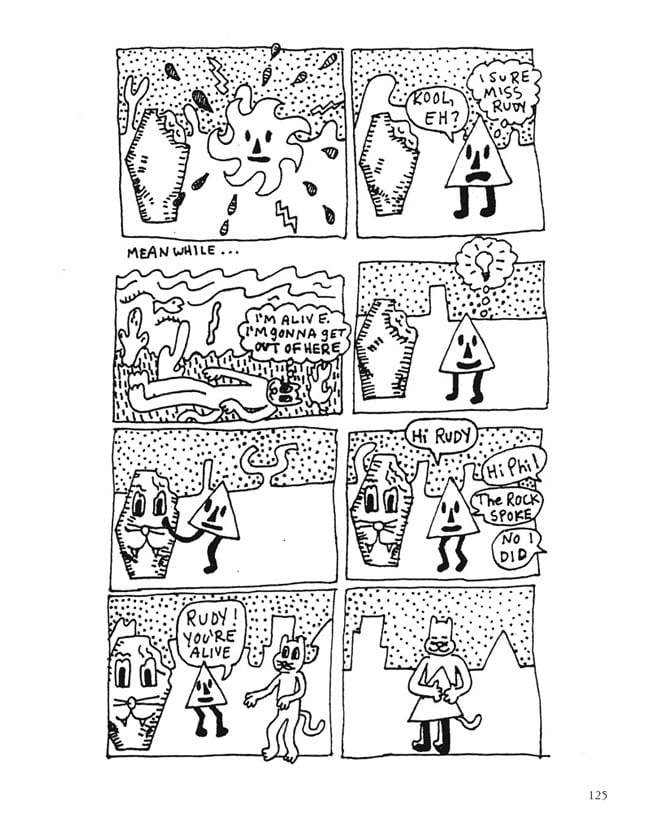

Rudy, our hero, is a tall feline fellow. The other major characters in his surreal universe are Ken, a two-legged, no-handed manfish who wears trousers, and Phil, a sentient triangle with (it has to be said) a really cute little face and two legs, which he uses as hands to make telephone calls. These three alternately align or oppose one another from strip to strip, depending on the whims of their creator. We only occasionally see females in their world – there’s Rudy’s mom, Mrs. Katt, and Trudy, Rudy’s girlfriend. There’s also the evil Cybernaut, who shows up from the skies intermittently to cause trouble for everyone.

In the classic comic strip Krazy Kat, the landscape constantly shifted from panel-to-panel. In Rudy it’s the actual physicality of the characters that shifts, matching the variable, surreal narratives. Their body-morphing is, in fact, a constantly recurring theme. Rudy and his pals shape-shift (at one point Rudy turns himself into a chair), steal one another’s brains, materialize and dematerialize, and develop other strange powers. In one memorable issue from 1996 Rudy’s body disappears, leaving only one of his large arch-shaped eyes visible. “Perfection,” he says. But then his girlfriend Trudy decides she must leave him, explaining quite reasonably to Ken the manfish, “He temporarily became an eyeball.” On the plus side, Eyeball Rudy does get to meet Eyeball Donald and Eyeball Mickey (guess their last names) for a pretty much historic meeting of classic cartoon character eyeballs. When another eyeball shows up, it turns out to be from a real-life cartoon character, Don Knotts. Knotts' eyeball won’t leave and becomes rather annoying, just like his real-life counterpart. Connery’s experimentation with the comics form is playful and stoopid, not academic.

Other aspects of these comics are fluid as well. At the outset of “Alternative Lifestyle” Phil says, “I’m sick of getting my vertex fucked by Rudy and Ken is so scaly. I’m going to get a girlfriend.” Phil goes to the mall singing “These Foolish Things” and when he meets up with Trudy he exclaims, “I could fall for her!” But to his surprise Trudy is actually Rudy in a dress. “I just decided to start dressing like a lady,” T/Rudy says, leaving poor heterosexual Phil the triangle heartbroken. “In this sad world there are no certainties,” the concluding narration reminds us. In a companion strip, “A Date with Mr. Baby”, a suddenly non-hetero Rudy is lured to the creepy-looking Mr. Baby’s pad with the possibility of romance: “Maybe you could be the boneless chicken breast in the frying pan of my love.” Things don’t go well at all, but it was nice to see Rudy open to all kinds of “alternative lifestyles,” if even for just one issue.

There’s actually a genuinely poetic feel to many pages. One scrawlier than usual strip finds Rudy in his Castle of Solitude, sick of everyone and everything; he just wants to play with his troll dolls there without interruption. The page concludes on a quiet note: “The days and weeks pass as if in a hashish trance.” Connery often pastes in quilts of found text in the margins, creating odd juxtapositions and an attractive art-zine texture. Underneath one four-panel comic is the typed, cobbled-together sentence, “In one series of experiments, catching a mouse affects feelings about ESP.”

Connery’s drawings and general Just-Because approach to comics remind me of other cartoonists with similar aesthetics, such as Nick Leonard (probably best known for his contributions to '90s zines like Baby Split Bowling News and Holy Titclamps), Martha Keavney (Badly Drawn Comics), the five-minute comics of Joey Alison Sayers, and even Liz Hickey’s Jammers comic from Hic & Hoc last year. The complete instability of a narrative structure combined with the free-form artlessness of his line creates a rare sort of sublime nonsense. It is much harder to successfully pull off these kinds of comics than it looks. A few non-Rudy features in the back of the book don’t hit the mark, such as the rather incoherent "Boogy Boy's House of Horror", which just doesn’t have that certain Rudy spark. But no matter: the vast majority of the book is a rare treat (to be more specific it’s a treat of rarities), and something of a rebuke to those who demand formalistic expertise and rigorously adhered-to aesthetic principles from comics. There is real art in Rudy's artlessness. Above all, Rudy comics just want to have fun.