A Ghost Returns

Like an old bottle bobbing up on an island decades after it has been hurled outward by unseen hands, Comix Book, a singular creation of 1970s comic art, has come back. Actually, the unseen hands are mostly those of a boom-and-bust market for comic art, and the object returned is perhaps even more time-worn than blurry glass. We are looking, here, at comics seen in a way now almost impossible to bring back to our perception in the twenty-first century. How did things change so fast and what is this?

Let’s jump into the time machine, landing in the early 1970s when hard-working Denis Kitchen established a midcoast comics empire in a former Mukluk factory of little Princeton, Wisconsin. He did not have many titles, but an occasional Crumb could sell several hundred thousand and he had the editorial courage of his convictions, with gay-themed comics and dare-to-bust-us dope-celebrating comics.

Kitchen badly wanted a breakthrough, and he always Thought Big. In those days, before multiplying big-budget superhero films, no one was bigger in comics than Stan Lee. Kitchen's idea was to get Marvel on board as publisher and distributor of what was, in fact, a stepchild of the Undergrounds. And probably just in time because the cops were hovering over the head shops that sold comix; worse, the counter-culture generation was steadily less counter, the former hipsters’ culture more mainstream. Time was actually running out, although that only become abundantly clear and final a few years later. Lee had also sought to lure Kitchen to New York and mainstream comics a couple times, and no doubt that smoothed the way to a business partnership of sorts.

According to plans, Comix Book would be able to publish nudity/sexuality and four-letter words within limits, limits that were far more constraining than the limitless freedom of the Underground Comix but further out than any mainstream firm had up to then been willing to go. Lee and Marvel would get the copyright—a highly sensitive issue for the artists—but also pay $100/page, and find or create an audience (through a print run of 200,000) otherwise unimaginable for such art. Kitchen would make the editorial decisions himself, far from Manhattan.

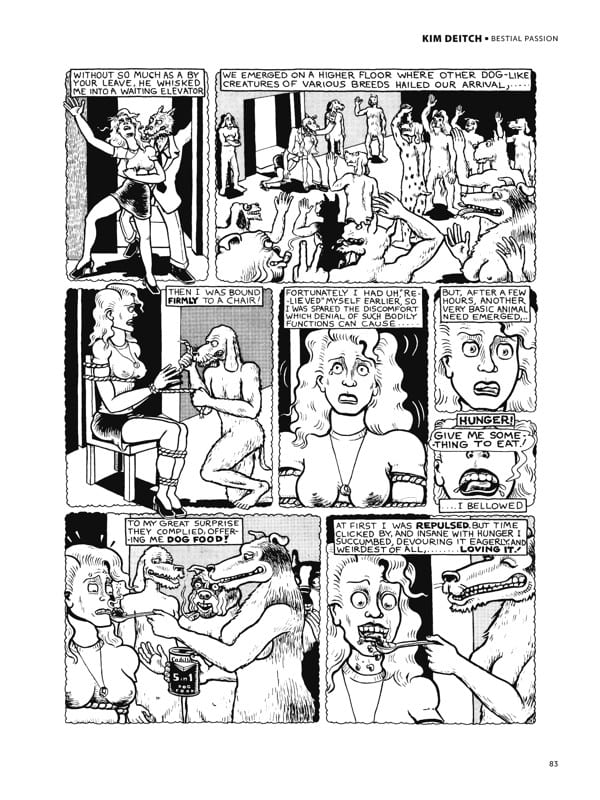

A generous handful of great artists from the little pool of the undergrounds signed on. Just to name a few: Trina Robbins, the mother-figure of women’s comix; Kim Deitch (who happened to be her ex), gay artist Howard Cruse; Justin Green, already famed for his autobiographical-psychological explorations; and an almost unbelievable name for something near underground, the evangelical Christian weirdo legend, Basil Wolverton. Comix Book was slated first for monthly and then, more realistically, bi-monthly production.

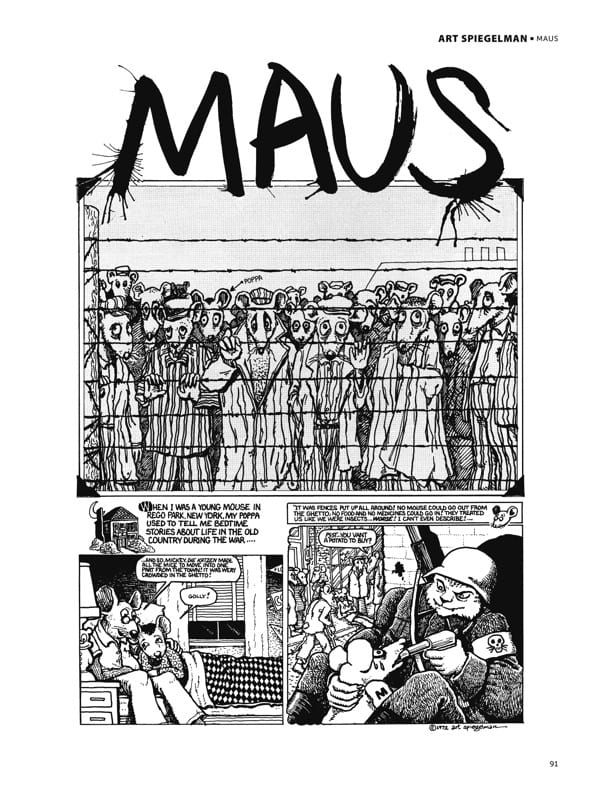

The art was truly astounding. Artists enjoyed enormous freedom for length and content, again within some limits. Sex and violence were more ridiculed than exploited. Campy memories of past genres, print, film and musical, were explored lovingly, turned around for what we might call an immanent critique, the view from the inside. Even a small, early chunk of Art Spiegelman’s Maus appeared here first.

Most remarkable in an artistic sense, to this reviewer, is the blending of the counter-culture anti-establishment politics of that era’s artists with the frequent sense of looking backward. Most of Comix Book’s contributors were, without thinking about it too intensely (or perhaps consciously), mining the veins of a popular culture scarcely ever aware of itself. The forward-looking 1960s had yielded to a backward-looking 1970s, exactly because the vernacular cultural totems so yearned for were now increasingly, hopelessly out of sight. The sources of comic art were themselves deeply embedded in the popular cultural world already slipping away, with the expansion of suburbs, the draining of life in the streets of the aging cities, and the glum feeling that “oldies” had come to stay for a reason.

By issue #5, the game was up. Marvel pulled the title. Kitchen wheedled Stan Lee to get the art back for two issues, and drew upon his own field of talent to make them unique. Even Harvey Pekar made an appearance. As a consolation, Kitchen Sink enjoyed some anthological glory, and recovered a bit of a slipping comic market. One might say that Comix Book’s demise also made the rise of Arcade, a more specialized and arty anthology series, possible. That series, edited by Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman, only lasted seven issues. With the close of the 1970s, it was goodbye Undergrounds.

Stan Lee doesn’t have much to say in his own introduction to this volume, but salutes Kitchen for producing a quality product, albeit not the all-out no-holds-barred version of the undergrounds sold under the commercial counter. He’s probably right: it was the compromise nature that may have killed Comix Book.

Then again, times had changed, people had changed, and the object in front of us may be best understood as that old mix of art and commerce. Or not “understood” so much as enjoyed because, it is own terms, it is a remarkable collection.##

Paul Buhle is still sorry there was no follow up to Radical America Komiks (1969).