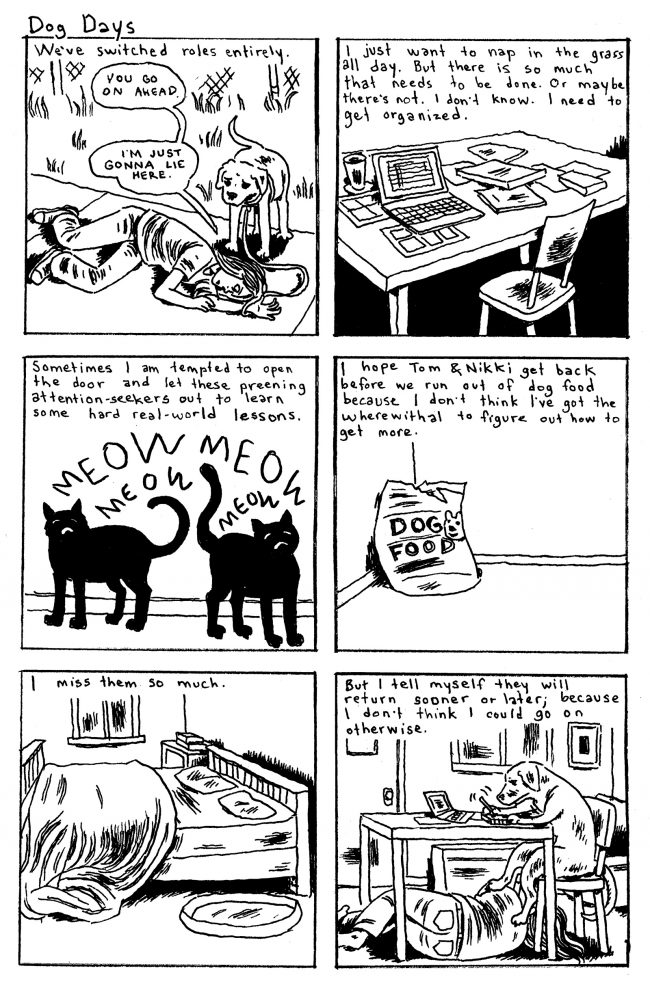

Gabrielle Bell has been drawing daily comics in July for something like 10 years now, all in a format she’s perfected: one-page, six-panel strips three high by two wide, black and white. My Dog Ivy collects the ones from 2017, when she animal sat for cartoonist Tom Kaczynski and his partner Nikki. Kaczynski owns Uncivilized Books, which put out this book in October of this year. He also owns Ivy, and the title of the book is followed by an asterisk, which indicates “It’s not my dog.” Like all of Bell’s work, it is surprisingly immersive and affecting, but why? How does she do it?

Formal analysis of Bell’s comics is difficult. They’re quite simple in many ways, including that almost unvarying structure, but they also have a lot more going on than, for example, Zen dude John Porcellino’s work. One thing Bell isn’t doing is trying to reduce things to their most essential components. When she draws a dog or a tree or a jar of peanut butter, it’s a specific dog or tree or jar of peanut butter, not some kind of Platonic ideal of the form. On the other hand, she doesn’t include so many details that you’d easily be able to pick that thing out of a line-up of other, similar things. She doesn’t have the cleanest line. One July, she drew her daily strips with her left hand to rest her right. She’s in the vast middle ground between Porcellino and Carol Tyler, along with a lot of other cartoonists, which isn’t bad but means that that ground isn’t what sets her apart.

As far as I can tell, she doesn’t do anything tremendously formally innovative either. It doesn’t seem to be what interests her. Her work is easily understood while not exactly neat. Sometimes a story continues from strip to strip and sometimes it doesn’t. Most of them are pretty straightforward stories from her life, without grand adventures. So how does she fit into the tradition of confessional comics and how does she end up being such a good storyteller? Unlike Lucy Knisley or Raina Telgemeier, her work isn’t all neat and planned out, following traditional narrative arcs. She tells us a lot about herself but not as much as Julie Doucet or Aline Kominsky-Crumb do. She loves animals and drawing them but doesn’t spend as much time on it as a lot of cartoonists. We feel like we’re dipping into and out of her life, but it doesn’t get repetitive. She’s not eating the same meal over and over or going to the same places. Dudes tend to fall into this trap a lot in their autobiographical work, listing movies seen or albums bought or places visited, using these lists as a shorthand for personality (see High Fidelity for many, many examples).

I tend to get itchy and irritated when I read stories like Bell’s. Where’s the progress? Why are you talking so much? Why should I care what’s going on in your life when I don’t even know you? Why do you keep mentioning people I also don’t know as though I should? It’s like someone telling you their dream: not interesting unless it’s yours. Bell does this too from time to time. She’s good at both. She keeps you involved somehow. She often puts way too many words on the page, but her work isn’t good only because she knows how to write a story. If I had to pick a word to characterize it, I might pick “mercurial.” That word gets a bad rap, at least from people like me, who prize stability and steadiness in life, but maybe it’s a good thing when it comes to art. It means that Bell can make a book called My Dog Ivy about a dog who does not actually belong to her and that she can reveal that fact on the cover. Some of these page-long comics are straightforward, with a beginning, middle, and end. Some feature word balloons that cover up the heads of almost everyone in a panel. Many don’t include balloon at all, but just a whole bunch of text, seeping into other parts of the panel. Some flip the script and have Ivy writing and drawing, but not exactly in a Family Circus way. Some have loads of words and others very few. One ends with Bell saying, “I miscalculated how many panels this strip would take, and I’m left with one extra, which I will use to show Monkey [a cat] tormenting me in her adorable/annoying way.” The previous panel includes a small “the end” in its bottom righthand corner.

I tend to get itchy and irritated when I read stories like Bell’s. Where’s the progress? Why are you talking so much? Why should I care what’s going on in your life when I don’t even know you? Why do you keep mentioning people I also don’t know as though I should? It’s like someone telling you their dream: not interesting unless it’s yours. Bell does this too from time to time. She’s good at both. She keeps you involved somehow. She often puts way too many words on the page, but her work isn’t good only because she knows how to write a story. If I had to pick a word to characterize it, I might pick “mercurial.” That word gets a bad rap, at least from people like me, who prize stability and steadiness in life, but maybe it’s a good thing when it comes to art. It means that Bell can make a book called My Dog Ivy about a dog who does not actually belong to her and that she can reveal that fact on the cover. Some of these page-long comics are straightforward, with a beginning, middle, and end. Some feature word balloons that cover up the heads of almost everyone in a panel. Many don’t include balloon at all, but just a whole bunch of text, seeping into other parts of the panel. Some flip the script and have Ivy writing and drawing, but not exactly in a Family Circus way. Some have loads of words and others very few. One ends with Bell saying, “I miscalculated how many panels this strip would take, and I’m left with one extra, which I will use to show Monkey [a cat] tormenting me in her adorable/annoying way.” The previous panel includes a small “the end” in its bottom righthand corner.

Things can change in a hurry, mid-strip. We can start in reality and end in a postapocalyptic wasteland populated largely by hagfish. It is, basically, hard to predict, and that quality is what keeps one from getting bored. Bell puts herself in new situations that aren’t necessarily comfortable for her; this is especially true of travel but also of her choosing to live in Brooklyn. The city is always full of new things waiting to be seen, the sheer number of people and things combining in unexpected ways all the time, a factor of math more than of anything else. If you have the choice to live other places and you don’t, it’s because you probably crave those encounters with novelty. For the same reason, you might agree to pet-sit for your friends for a month in a town where you don’t live. Your brain gets restless if it doesn’t have neurons lighting up new pathways. And if your mind works this way, you probably assume that others’ minds do, too, which means you make comics like My Dog Ivy and all of Bell’s other work, short and long.

Things can change in a hurry, mid-strip. We can start in reality and end in a postapocalyptic wasteland populated largely by hagfish. It is, basically, hard to predict, and that quality is what keeps one from getting bored. Bell puts herself in new situations that aren’t necessarily comfortable for her; this is especially true of travel but also of her choosing to live in Brooklyn. The city is always full of new things waiting to be seen, the sheer number of people and things combining in unexpected ways all the time, a factor of math more than of anything else. If you have the choice to live other places and you don’t, it’s because you probably crave those encounters with novelty. For the same reason, you might agree to pet-sit for your friends for a month in a town where you don’t live. Your brain gets restless if it doesn’t have neurons lighting up new pathways. And if your mind works this way, you probably assume that others’ minds do, too, which means you make comics like My Dog Ivy and all of Bell’s other work, short and long.