Jack Kirby's Machine Man belongs to multiple worlds, both on the level of plot and in the circumstances of its creation. Kirby devised Machine Man (aka X-51, aka Aaron Stack) during his return to Marvel in the late '70s, as a character in his loose adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Although the company’s license to publish 2001 comics later expired, Machine Man fell under Marvel IP and fell into the Marvel universe, wrestling with rival robots, the US military, and his own existential malaise. The character's name sums it up—he’s machine and man, an artificial intelligence that insists on its humanity. Machine Man: The Complete Collection covers the character’s brief post-2001 series, including Kirby’s issues (the first nine), a few installments of The Incredible Hulk featuring X-51, and issues 10 through 19, for which Steve Ditko provided art. These comics are not the best-remembered work of either artist, but the exceptional talents of Kirby and Ditko, balanced against the stories’ missteps, make the collection a fascinating, multifaceted book—no ordinary mixed bag.

Kirby and Ditko were major figures in one of the most concentrated rushes of creativity in American popular culture, but by the time Marvel first published Machine Man, both of them were also men without a country inside the company. Each artist had, independently, fallen out with mutual collaborator Stan Lee; each artist had spent time away from Marvel, creating characters for the competition. And although Kirby writes his own stories throughout his Machine Man run, with Ditko illustrating the scripts of Marv Wolfman and Tom DeFalco, both the Kirby and the Dikto issues read as the work of cartoonists whose sensibilities were not of the current era.

This disconnect is clear on the covers to certain early issues, when unsympathetic inkers attempt to drag Kirby’s pencils closer toward Marvel’s late-seventies house style. (Mike Royer inks the interior pencils for Kirby’s issues, and he’s more observant of the art’s demand for large spot blacks and clean contours.) But if some readers of the time balked at these comics, they were partly justified. When drawing menswear, for instance, neither Kirby nor Ditko seems to have noticed any changes in fashion in the two decades prior to these comics’ release. (This is especially puzzling with Kirby, who created the Forever People, essentially a band of super-hippies, during his time with DC.) It’s a minor thing that nevertheless raises the question of the expected audience for Machine Man—a question that Marvel editorial may also have raised, as the series was capped during its second year.

Even outside of Machine Man’s eventual cancellation, or Kirby’s departure from the book before that, The Complete Collection has the problems of any Marvel repackaging or adaptation of Kirby characters. It’s sometimes difficult to read these comics without also considering Marvel’s fraught relationship with Kirby’s estate, or without contrasting the profile of Kirby’s characters and the modest rewards he reaped in his lifetime. But a reader reckoning with the collection will at least find reminders of why Kirby’s legacy endures—and some of them may be surprising.

Even outside of Machine Man’s eventual cancellation, or Kirby’s departure from the book before that, The Complete Collection has the problems of any Marvel repackaging or adaptation of Kirby characters. It’s sometimes difficult to read these comics without also considering Marvel’s fraught relationship with Kirby’s estate, or without contrasting the profile of Kirby’s characters and the modest rewards he reaped in his lifetime. But a reader reckoning with the collection will at least find reminders of why Kirby’s legacy endures—and some of them may be surprising.

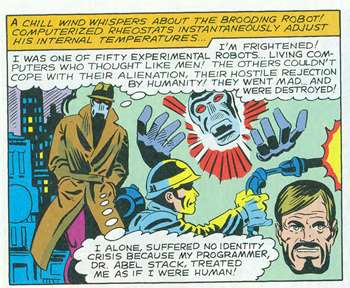

The cliché about Kirby’s prose is, after years of drawing tight, dynamic layouts that Stan Lee would then crowd with clumps of cheeky verbosity, Kirby’s self-scripted '70s output was grossly overwritten in its own right. Machine Man: The Complete Collection may not convert hardened skeptics, but the book makes as strong a case as any for Kirby’s way with words. The lines throughout the page below, for instance, barely resemble real human speech, but they’re blessed with a rhythm and an internal consistency that Kirby doesn’t always get credit for. His dialogue captures a kind of pugilistic pop philosophizing that suits the superhero genre’s bleed between text and subtext.

(The scripting in the Ditko issues is less remarkable—a reader can skip the captions and miss little—though in some of the later issues, Tom DeFalco leans into the absurdity of the concept with lines like “One mashes potatoes or turnips … but not robots!” and “Wake up, fleshy! Tell me how to find your sexy superior!”)

Kirby’s nearly synonymous with action, of course, and in Machine Man, he executes it as cleanly, powerfully, and effectively as in any other stage of his career. Each conflict is rendered in a manner that gives the physiques of Machine Man and his adversaries striking presence and weight. A reader can intuit Kirby’s delight in the possibilities of a character with a changeable body. In one issue, for instance, a damaged Machine Man borrows spare parts from a mechanic and proceeds to more or less make a car out of himself.

This sense of possibility extends to breaks from the action: X-51 turns rocks into diamonds to pay the mechanic, lights a friend’s cigar with a laser beam, and so forth. Even when a dejected Machine Man considers turning his back on humankind, Kirby can’t leave his lead brooding on a rooftop for more than a panel or two—locals quickly persuade Machine Man to stop by a costume party, which Kirby draws like an especially festive corner of New Genesis.

Unfortunately, the issues of Machine Man that Ditko illustrates (he’s inking his own pencils here) don’t fit easily among Ditko’s best works. Like Kirby, Ditko gets some mileage out of Machine Man’s modular anatomy and extendable limbs, with sequences like the one above providing him with the chance to draw a series of alien contortions that even Spider-Man didn’t allow. By and large, though, a mechanical protagonist seems to restrain the possibilities of Ditko’s art more than it expands them.

If there’s one thing Kirby and Ditko have in common, beyond some shared historical circumstances, it may be anguish—the gift for depicting it and an accord with characters hit by it. Even with the improvisatory whimsy in Kirby’s run, his stories can turn nightmarish at a moment’s notice.

If there’s one thing Kirby and Ditko have in common, beyond some shared historical circumstances, it may be anguish—the gift for depicting it and an accord with characters hit by it. Even with the improvisatory whimsy in Kirby’s run, his stories can turn nightmarish at a moment’s notice.

This tonal whiplash is not unique to Machine Man, but it is a fixture of the best of Jack Kirby. One of Kirby’s neat tricks in these stories, the kind of literalizing of the thematic that superhero books can do well, is the protagonist’s detachable face (seen above). What X-51 considers his true likeness is—on a physical level—removable, with all the build-in psychological instability this creates. With respect to this imagery, Ditko does Kirby one better. His issues house a few indelible images, not the least of which is Machine Man’s detached, levitating head, emerging half-melted from a fire.

This sequence takes place in the midst of a team-up with Alpha Flight (which might as well be shorthand for the dullest sort of Marvel comic), and it may have been intended to project typical misunderstood-hero pathos, but it probably gave kids nightmares instead, with the weird potential of Ditko’s cartooning intruding on an otherwise boilerplate superhero story.

This sequence takes place in the midst of a team-up with Alpha Flight (which might as well be shorthand for the dullest sort of Marvel comic), and it may have been intended to project typical misunderstood-hero pathos, but it probably gave kids nightmares instead, with the weird potential of Ditko’s cartooning intruding on an otherwise boilerplate superhero story.

(Due credit to Marv Wolfman and Tom DeFalco: There’s a surprising morbidity to the whole post-Kirby run, including the accidental death of a villain who crashes into wires in the middle of a fight and another, freak-of-science-type antagonist who flails around beginning to be killed.)

The appeal of late-'70s Machine Man as a curiosity is on full display in the final installment of the series. Issue 19 features cover art not by Ditko but by Frank Miller, who draws Machine Man and a villain doing battle in the midst of, essentially, superhero cosplayers. (We learn they’re attendees of a costume party). The villain, making his debut, is Jack O’Lantern, which means Ditko himself is drawing an intra-Marvel knockoff of the Green Goblin, one of his sixties co-creations. Stranger still: for a portion of this issue, Machine Man, his human face disfigured, walks around in a trench coat, shading his robot visage with the brim of a rimmed hat. He resembles no character more than Rorschach of Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s damaged amalgam of Ditko creations the Question and Mr. A.

The appeal of late-'70s Machine Man as a curiosity is on full display in the final installment of the series. Issue 19 features cover art not by Ditko but by Frank Miller, who draws Machine Man and a villain doing battle in the midst of, essentially, superhero cosplayers. (We learn they’re attendees of a costume party). The villain, making his debut, is Jack O’Lantern, which means Ditko himself is drawing an intra-Marvel knockoff of the Green Goblin, one of his sixties co-creations. Stranger still: for a portion of this issue, Machine Man, his human face disfigured, walks around in a trench coat, shading his robot visage with the brim of a rimmed hat. He resembles no character more than Rorschach of Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s damaged amalgam of Ditko creations the Question and Mr. A.

Together, these elements make the issue read more like a transmitter, catching signals from the past and future of superhero books, than a proper superhero comic. (One short sequence wouldn’t be out of place in The Bulletproof Coffin, as a child dressed as Superman, his costume’s mask lending him an adult-sized head, asks Machine Man, “What’s your angle, creep?) In other words: Machine Man went out the way it went in, on the reverberations of other stories. A unified theory of this issue would probably blur or ignore some of its actual historical particulars, but if nothing else, it’s an appropriate ending for the series—an oddity with the power to surprise.