The back cover for this hefty anthology of comics by Scandinavian artists suggests it be filed under “Nordic Hypnotica,” which is entirely apropos. Don’t go into this anticipating only traditional cartooning and straightforward storytelling. Get ready to encounter a generous sampling of elliptical, experimental, formalist, and occasionally downright eccentric pieces by a diverse group of artists all too eager to give your eyes and brain an extra workout.

Klimax works well as both a follow-up and an expansion of the In the Shadow of the Northern Lights anthologies (2008 & 2010, Top Shelf), which were limited to Swedish cartoonists, and From Wonderland with Love (2009, Fantagraphics), which was devoted to Danish artists. Klimax adds artists from Finland and Norway to the talent roster. In his introduction, editor Matthias Wivel helpfully distinguishes some of the aesthetic traditions of the various countries. The Finns, for example, with less of a comics tradition to fall back on, tend to favor experimentation and creative freedom. Artists from Norway are often the opposite; their comics scene has sprung from more traditional, commercially-based roots. Meanwhile, the Swedish artists tend to create more reality-based and autobio work, while the Danes, skewing southward, have traditionally been more influenced by Franco-Belgian album comics and American comic strips. Whatever the countries’ aesthetic differences, their work melds together successfully; the result is a wide-ranging, vibrant collection that should be enjoyed by fans of the burgeoning European alt-comics scene as well as anyone with an art comics bent.

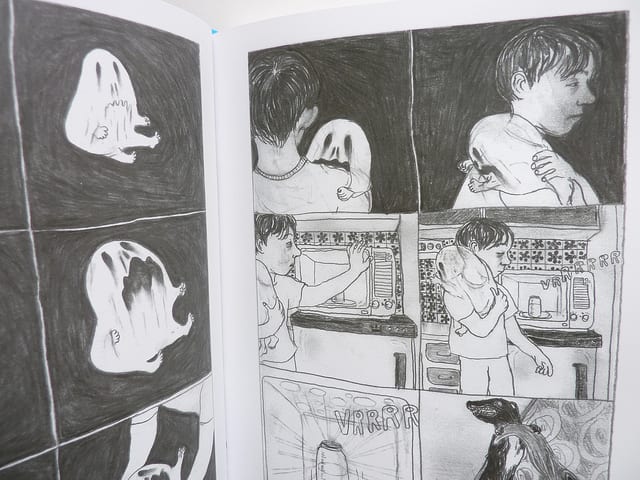

I was happy to see two of my favorite Nordic creators included: Finland’s Amanda Vähämäki and Sweden’s Kolbeinn Karlsson. Vähämäki offers “In the Night,” another of her sublimely surreal phantasms captured in her signature creepy-charming smudged pencil style. Vähämäki’s stories often tap into the reveries, struggles and anxieties of childhood, effortlessly skirting the line between dream and nightmare. Here we see a young child bottle-feeding and comforting a whining, monstrous-looking infant while watching alternately lewd and inane television commercials as a dark storm brews outside. As is often the case in Vähämäki’s work, the narrative is loose and doesn’t so much end as just stop, seemingly arbitrarily, as in a dream.

Karlsson contributes “10,000,000 BC”, an amusing, charmingly scatological look at how the mating instincts of a pair of prehistoric beasts become preserved in time, ultimately for the delectation of a group of giggling schoolgirls. With its big, bold color graphics and the recurring theme of the pitiless power of nature, the piece ties in nicely to Karlsson’s trippy graphic novel of woodland magic and ritual, The Troll King (2010).

Johan F. Krarup of Denmark gives us the powerful autobio “Nostalgia”, which finds the author visiting an online acquaintance, a newly divorced and emotionally struggling comics and toy collector named Berti. At the story’s conclusion Berti shows Johan the unattached pieces of his vintage Lego set, laid out in neat symmetry. Missing his daughters, he tells Johan, “I consoled myself with my Legos.” The sight of the brightly colored pieces — his only buffer against existential emptiness and pain — is quietly heartbreaking.

“Escalator” by Norway’s Christopher Nielsen is a simple but efficient and clever allegory about fear and conformity, while Sweden’s Joanna Hellgren in “Scout” depicts a group of arrogant teens that party at a seemingly abandoned camp in the woods. They are confronted not by a hulking masked maniac with a machete, but something perhaps even more unsettling: a mysterious troop of scouts who make them clean up their beer bottles before driving them off the property with moralistic verbal abuse (“Your brain activity is disturbed by hormones!”). Hellgren’s penciled pages look quite similar to Amanda Vähämäki’s, though more angular, with a more naïve feel. It’s good stuff.

Tommi Musturi (Finland) is represented by three of his delightful “Samuel” pantomime strips, each a fantasy-scape of movement and gorgeous color that are, as the publisher notes, reminiscent of Jim Woodring’s Frank strips.

I don’t profess to be a Scandinavian comics expert but I was disappointed that two others of my favorite artists, Anneli Furmark and Benjamin Stengard, were not included (Wivel mentions in his introduction his inability to get certain key creators in these pages). Furmark’s understated character-oriented work has gotten some exposure here in the States but is still under-appreciated; Stengard produces gripping, genuinely unsettling tales of unease and psychological horror. I was happy, however, to come across the fine work of several more artists with whom I was previously unfamiliar, chief among them are the Danish duo of Mikkel Damsbo & Gitte Broeng, with their skillfully crafted existential reverie on place and identity, "Relocating Mother", and Jenni Rope of Finland, who contributes “The Island”, a two-part meditation on loneliness vs. solitude, beautifully rendered in minimalist black & white drawings. There’s also “This is My Life", a clever satirical autobiography by highly respected Swedish cartoonist Joakim Pirinen.

Less interesting for me are Mari Ahokoivu’s “S-w-i-n-g”, which plays well with its panels and layout but offers little beyond a clever formalist conceit; “Always Prepared to Die for My Child”, by Sweden’s Joanna Rubin Dranger, a funny but over-extended riff on parental anxiety; and Peter Kielland’s character Mr. Pig in “I Own the Night”, a well-rendered but routine pantomime parody of the “9-to-5 working stiff” trope

Two of the more puzzling entries include “The Great Underneath” by Norwegian artist Benedik Kaltenborn, a perplexing noir rendered in simple humorous drawings and bright solid colors that belie its dark core of inexplicable evil and bloodshed, while “Yellow Cloud” by Emelie Ostergren is a surpassingly odd, surreal mood piece. Rather than imparting clarity these initially off-putting stories offer instead narrative possibility; I found myself drawn back to each several times.

That, for me, is the common vibe generated by this and other Euro-comics anthologies (such as the Latvian series Kuš): the sense of possibility and novelty that comes from having available a whole new frontier of previously hard-to-come-by alt-comics by accomplished artists to explore. Comics speak a universal, intuitive language, but this “Nordic Hypnotica” opens Americans up to previously unfamiliar dialects that are a pleasure to read, enjoy, and occasionally decode.