Not much happens in Jon McNaught's latest graphic novel Kingdom. A mother takes her son and daughter to Kingdom Fields Holiday Park, a vacation lodge on the British coast. There, they watch television, go to a run-down museum, play on the beach, walk the hills, and visit an old aunt. Then they go home. There is no climactic event, no terrible trial to endure. There is no crisis, no trauma. And yet it's clear that the holiday in Kingdom Fields will remain forever with the children, embedded into their consciousness as a series of strange aesthetic impressions. Not much happens in Kingdom, but what does happen feels vital and real.

"Life, friends, is boring," the poet John Berryman wrote in his fourteenth Dream Song, before quickly appending, "We must not say so / After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns." In Kingdom, McNaught creates a world of flashing sky and yearning sea, natural splendor populated by birds and bats, mice and moths. In Kingdom Fields, waves crash in gorgeous dark blues, the sun rises in golden pinks, rain teems down in violet swirls, and the wind breezes through meadows of grass. It's all very gorgeous, and the trio of main characters spend quite a bit of the novel ignoring it. The narrator of John Berryman's fourteenth Dream Song understood the transcendental promise of nature's majesty, yet also understood that "the mountain or sea or sky" alone are not enough for humans---that we are of nature and yet apart from it.

The unnamed mother in Kingdom takes her children to Kingdom Fields so that they can connect to the natural world. She yearns to replicate the holiday visits she enjoyed decades ago, when she and her younger brother were the same age as her own children are now. Her sullen son Andrew wants none of it though. His teenage angst percolates in a restless, vaguely-mean boredom. When his mother tries to tell them about Kingdom Fields -- "It was my favourite place in the world when I was your age" -- he tunes her out.

The unnamed mother in Kingdom takes her children to Kingdom Fields so that they can connect to the natural world. She yearns to replicate the holiday visits she enjoyed decades ago, when she and her younger brother were the same age as her own children are now. Her sullen son Andrew wants none of it though. His teenage angst percolates in a restless, vaguely-mean boredom. When his mother tries to tell them about Kingdom Fields -- "It was my favourite place in the world when I was your age" -- he tunes her out.

In Kingdom, McNaught frequently uses the sounds of the natural world--here, ice clinking in a cup--to eclipse verbal, spoken communication. When characters do communicate through speech, it is usually for trite, commercial purposes. The first dialogue of the novel is an economic exchange at a Burger King in a travel plaza. It is one of the only moments where articulated speech actually achieves its goal of communication.

Language in Kingdom is etiolated; the dialogue is spare, and characters rarely seem to listen to each other. Words are deployed more as a kind of visual phenomena of space---labels, brands, signs, placards, advertising copy, and graffiti adorn panel after panel, their meaning and context crowded and blurred away into a blanket of non-signification.

The sounds of the natural world mean more in Kingdom than articulated language. The book buzzes with aural life force --- the "SCUFFLE SCRATCH" of mice, the "ARK" of gulls, the "CHICHI" of long grasses rustling in the coastal wind, the "BZZZ" of flies eating garbage, and the "MUNCH MUNCH" of a little girl eating french fries. She too is an animal, after all. The inorganic world makes noise in Kingdom too: cars, electronics, the blather of television, the dinging of video games.

In a telling little scene, Andrew plays a resource management game on a laptop; with a "CLICK" he "kills" a deer ("THUD"), which is then converted into "food" and "fuel." Outside in the natural world, the real world, the Darwinian spectacle of a bird catching a rat plays out in contrast.

Andrew mediates the "natural" world almost entirely through screens. In a visit to a crappy museum, instead of trying to learn about the geology or history of the area they are visiting, he plays games on his phone. And Suzie watches him play games. In another illustrative scene, Andrew sits glumly in a racing car game in an arcade--he has no money and cannot play the game, so he simply sits in the fake car, despite having complained just a page or too earlier about the length of the car trip to Kingdom Fields. In a beautiful, melancholy night scene, Andrew sits atop a hill bathed in gorgeous starlight, bats flitting about him as he ignores the curious cows that gather around. He is busy gazing at social media.

Younger sister Suzie, still a kid, is a bit more open to seeing the world in a perhaps-unmediated way. She hangs upside down from a jungle gym bar, swings high in the air on a playground, or spins around in circles. She visits the "mermaid's cave" with her mother, who sees it anew, its transcendental powers changed through the strange lenses of memory and time.

The mother is perhaps disappointed, but Suzie enthusiastically scours the cave for its treasure trove of trash---broken glass, beer bottle caps, a pizza slicer. The mother wants to pass down a fantasy to her daughter, to share a fragment of her own youth. What happens is not a direct transmission of a transcendent moment, not a recapitulation, but instead a synthesis. Suzie will anchor the images in her own mind, and perhaps return in decades to the cave to find that "it's not quite how" she remembered it either.

Suzie also accompanies her mother on a visit to Great Aunt Lizzie, a mini-trip that Andrew sullenly resists. The scene in Great Aunt Lizzie's dated house is wonderfully nostalgic, tinged with sorrow and bits of boredom. As Lizzie and her niece catch up, Suzie pores over the 1995 Guinness Book of Records. McNaught directs the elements of the scene with equal weight, showing us that whatever memories Suzie retains of her great aunt will be inextricably bound up with images of the world's longest fingernails, the world's largest tumor, and the world's fastest yo-yoer. McNaught masterfully conveys the ways in which recollections are forged, the ways in which aesthetic phenomena condense time and place into memory. Flowers pressed in a book, for example, may mark someone else's recollection, and yet an unexpected encounter with their aesthetic presence generates a new impression in a different person.

The scene with Great Aunt Lizzie concludes with a parallel to an earlier moment in the novel. The mother sees an old photograph of herself with her brother and Aunt Lizzie on the beach; the trio in the photograph are about the same age as Andrew, Lizzie, and their mother are now. The mother texts a digital pic of the old photograph to her brother, and quickly loses the immediate connection to Lizzie, tuning out her speech in favor of the dinging phone, much as Andrew had tuned her out earlier. Again, verbal communication is fleeting and destabilized in Kingdom; what remains are aesthetic impressions, shared images.

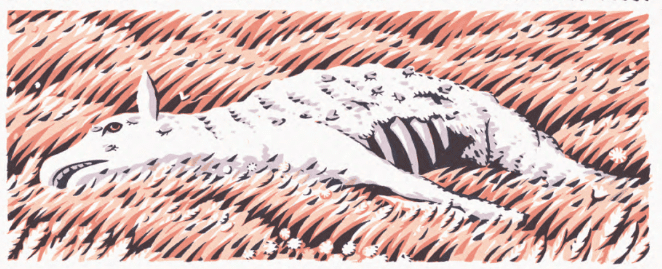

Although he can't communicate effectively with his mother or sister, moody Andrew does manage to connect with a boy named Ben, and the two share some mild adventures: they pretend to be snipers in a World War II pillbox; they share a clandestine beer; they night-swim. They come across the decaying body of a dead sheep, its posture echoing the dead deer in Andrew's video game. Again, these are the images we sense that Andrew will condense into his sense of place. His memories of Kingdom Field will be far richer and more complex than simple teenage boredom.

The complexity and ambiguity of age and place and its intersection with image and memory are at the core of Kingdom. There's something acutely real about its small details. The family members' experiences are hardly aesthetic revelations, yet they are aesthetic truths---ambiguous truths, memories. And that's what a family vacation is for, right? Making memories?

McNaught's novel is also a subtle meditation on our relationship with nature and how we frame nature, how we see nature in relation to ourselves. Can there be transcendental power in a natural world, where the "sky flashes [and] the great sea yearns" (to steal from John Berryman again)? Or does our post-postmodern framing of the world---technological, commercial, ironic---distance us from an encounter with the sublime? As it nears its conclusion, Kingdom offers something of a synthesis of perspectives, combining transcendentalism, naturalism, and post-postmodernism in an elegant series of panels. Andrew revisits the sheep's corpse, which has been picked apart by maggots. Its skeletal body is the natural counterpart to the virtual animal Andrew killed with a "CLICK" earlier in the novel. With another "KLIK" he brings it back into the digital world, to share on social media, to communicate the image, to mark and frame the memory.

Like McNaught's earlier works Dockwood and Birchfield Close, Kingdom reads like a visual poem, a sustained mood in impressionistic waves of washed-out pinks and blues. His pages are often loaded with panels--four by six panels is the standard in Kingdom, although at times he can expand to even pages of four by sevens---and yet the effect is never cramped. There's a filmic quality to McNaught's shots, a pacing and spacing reminiscent of Terrence Malick's films.

And like McNaught's earlier works, Kingdom isn't for everyone. Like I said at the top: Not much happens in Kingdom. What does happen though is difficult to pin down here in language though---which is fitting, as one of Kingdom's themes is the failure of articulated language to effectively communicate. What McNaught gives us in Kingdom is a feeling fraught with ambiguity---restless tranquility, joyful melancholy, pleasant waves of boredom. We can recognize in the narrative the non-narrative of our own lives, the little scraps and sequences and moods and motifs that we convert into experience, into memory, into our own sense of self. This strange recognition has a subtle but affecting power. It makes revisiting McNaught's work such a pleasure---and it makes me anticipate future volumes from the artist. Highly recommended.