What Is Going On: Some Reflections on Picking Up Gulag Casual

Hmmm.

Hemmm.

Well, well, well.

Of course, I think, dreams.

I smile.

Kafka, Beckett, Pinter occur.

The language, I consider, (A “brute” approaches to “pummel” someone”) is slightly off.

Familiar but not usual, I continue, it suits the sentence, the context but not the time and place beyond the story, book and page.

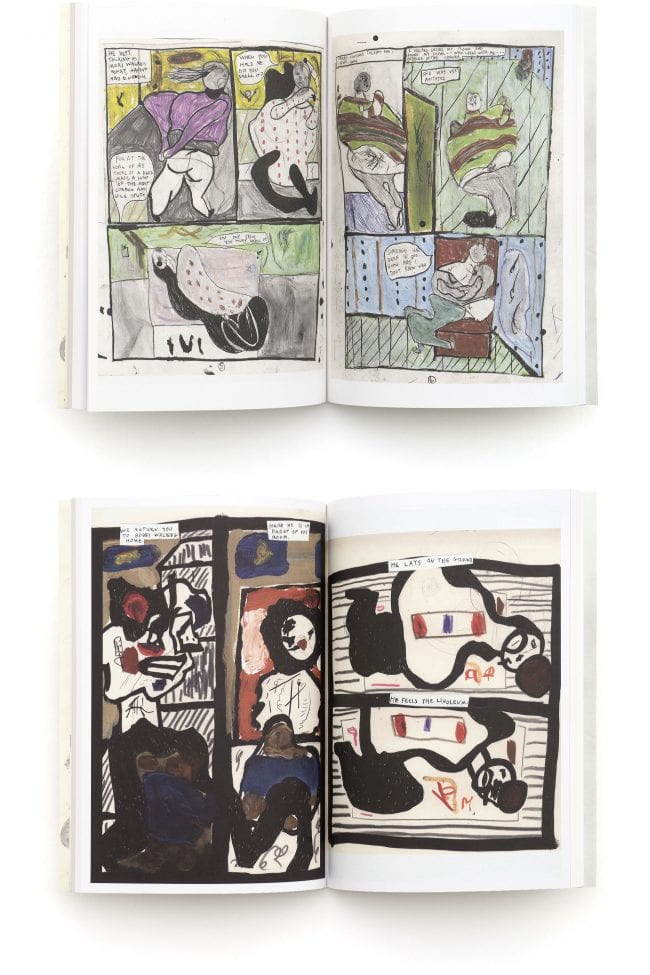

And sometimes, most of the time, the pictures... What are they?

Shapes, colors, faces, bodies.

But when this “are” is there, the connect to the words may not be.

Braque, de Kooning, Guston...

There must be meaning.

There is deliberate placement on the page.

The words and pictures have been chosen for each other.

Relationships! I think.

Connections!

“Gulag Casual, a collection of five stories created by Austin English between 2010 and 2015, swings open the attic of the mind and sweeps a corner clear of cobwebs, dust balls, and desiccated vermin.” I could write that.

II

I recently read a book in which a world-roaming architect selected drawings from 50 years of sketchbooks and set beside each a paragraph or three of associated memories on the facing page in order to render an account of his life’s journey. It was, I realized, a departure from the usual words-and-pictures work, where both elements are created within the same narrow window of time since, in the architect’s book, pictures may have been created a half-century before the words, with no idea that words would ever be matched to them. For one who has not thought about this much, like me, Gulag is an entirely different, but equally satisfying twist on the words-and-pictures trip.

It presents an urban world of houses, apartments, restaurants, and bars. (“...(W)hat goes on in that house?’ someone asks on page one, a question that lingers as other pages turn.) People have families, partners, roommates, upon whom strangers often intrude and from whom someone often strays. Bobby and Theo leave Margaret and Nicky. An anonymous narrator leaves Perry and Moki. A stranger leaves Olaf and his girlfiend. People often displease each other or themselves. Bobby calls Theo “a submoronic piece of filth.” An unidentified phone caller terms Bobby a “slimy fraud.” An anonymous narrator characterizes himself as “a lump of... common and vile stuff.” A stranger notes his mouth exudes “drool” and his nose “puss.”

People behave cruelly. They call one another “creep” or “fag” or “moron.” They abandon children and assault one another. They roll around on broken glass and have a bucket placed on their head and pounded. Judgments are made and instructions given (“If you have no ambition, you can love anyone”; “(It is admirable not to) need the milk of human kindness to keep (one) in check”); but they are voiced just-sufficiently enough to lack the authority to be compelling. One takes them in with the same bafflement that rises from all of Gulag. One is convinced something is there; but what?

The stories’ resolutions clarify nothing. A character lies on the sidewalk. A character lies on the floor. Three characters lie in bed. A vanished stranger’s “toxic presence” lingers.

III

(Gulag Casual reads as if) the characters and plot have been cooked to the point of softness, fallen off the bone, and mixed with flavors to the edge of recognition. -Priscilla Frank, The Huntington Post

So if that is your story, how do you illustrate it?

When mystery and ambiguity dominate the straightforward. When words can not capture meaning. When one is caused to continually wonder what is going on inside this house.

Realism is out of the question. Fine-lined minimalism would not bear the weight. Expressionistic superhero schtick would be to laugh.

From Priscilla Frank, I learned English grew up reading comics, while surrounded by his mother’s art books and images she had torn from art magazines and hung on walls. Comics and fine art became “equal” to him, without distinction or hierarchy. Both seemed “part of everyday life.”

This open-minded “everyday”-ness has led English to an aesthetic vision which enlivens the rough structure of the comic book/graaphc novel format with the adventurism of fine art exploration. While nodding toward narrative and sequential linkage, he has more fun erasing connectives and scrambling expectations than enhancing them. “The urge to break the rules,” he told Frank, “(became)... completely irresistible.” The result is a daring and entertaining grapple with the question of how a shape – a blob, a splash, a serpentine, viscous line – with or without eyes or nose or buttons or wall hangings – can advance action, foster feeling, convey meaning. Words provide some befogged clarity – give the mind a kick of “Oh yeah! A bed! A blanket! Legs!” But the visual is what makes Gulag go.

Take English’s use of color. It may be muted, pastel-like (“A New York Story”), or vibrant, if black-dominated (“The Disgusting Room”), or all graphite black/white/ grey (“Here I Am,” “Freddy’s Dead”). And since color influences perception, you can never be confident, story-to-story, about what sort of world into which you will be stepping.

Then, once entered, the footing becomes even slipperier. The representation of the physical and external is less important to English than the representation of the internal and emotional. Most basics of defining through detail – clothing, furniture, weather – are ignored. Facial expressions – even faces themselves – are depicted grossly, if at all. Characters blithely shift their appearance from panel-to-panel. Continuity is suggested to, but flux is the order of the day.

Nothing can be counted on within the “story” being told or in the rendering of it. If the panels were framed singly, all words removed, and hung on gallery walls, even in the same order of presentation, I doubt much would be recognized or if any narrative flow forth. But within this book they combine to communicate a drama of uneasiness Behavior is aberrant. Motivation, if expressed, rarely satisfies. Dreams are no more surreal than the everyday. Angers and resentments curdle inside nearly everyone. Solace is not found. The sun of meaning breaks through no clouds. But Gulag is so damn unique and vibrant and seductive-to-the-curious, it makes one’s spirit soar.

English has risked the consequences of deviating from the familiar, he has crafted through art a singular, satisfying response to the mysteries and vagaries of life. Which, from where I stand, is good. Gulag, in its originality and execution, is an expansion of human possibilities.