It’s said that great works of art are meant to be viewed at a distance from eye-level. Jillian Tamaki’s Boundless, inspires this same viewing condition. Tamaki's book design means she compels the reader to rotate the text vertically in the opening pages, urging her to engage with Boundless in a novel way. Rotating the text into the vertical position, the reader cannot help but hold it at arms length. The text requires perspective, interpretation, and closure, to either go past the boundaries of conventional story-telling with Tamaki, or otherwise close the conceptual divide Tamaki exploits. Boundless is composed of unrelenting questions. The gap between question and answer is as great a divide as any other in the text. Boundless’ opening questions, “Do you want to be my friend?” and “Do you want to look at art at 2AM?” immerse the reader in Tamaki’s story-world as active agents, co-constructors, and confidants to the text. This makes the unfolding narrative a personalized journey for answers along Tamaki’s interconnected double-page spreads. In this way, Tamaki ensnares the reader into her own carefully crafted story-web.

Tamaki applies her narrative voice and style to both human and natural subjects, resulting in a formlessness, or perhaps an erasure, between human and natural subjects. Lines such as “I get stronger with every passing day” are difficult to attribute to the water depicted in the scene or the person swimming within it. Similarly, affirmations such as “And I’m going to be respected” create a curious relation to either the worker shown carving a tree or the tree itself. This fluid relationship between Tamaki’s words and images provoke a captivating plurality, one that tumbles down one vertical double-page spread to another. At times, the human is relegated to the periphery of the page, clinging to subjectivity in the face of sprawling nature across the two-page spread; at other times, the reverse is true, with the human form clinging to its subjectivity while it views the world from a liminal position in Tamaki’s text. With each page, humanity and nature vie for a balanced co-existence.

Tamaki applies her narrative voice and style to both human and natural subjects, resulting in a formlessness, or perhaps an erasure, between human and natural subjects. Lines such as “I get stronger with every passing day” are difficult to attribute to the water depicted in the scene or the person swimming within it. Similarly, affirmations such as “And I’m going to be respected” create a curious relation to either the worker shown carving a tree or the tree itself. This fluid relationship between Tamaki’s words and images provoke a captivating plurality, one that tumbles down one vertical double-page spread to another. At times, the human is relegated to the periphery of the page, clinging to subjectivity in the face of sprawling nature across the two-page spread; at other times, the reverse is true, with the human form clinging to its subjectivity while it views the world from a liminal position in Tamaki’s text. With each page, humanity and nature vie for a balanced co-existence.

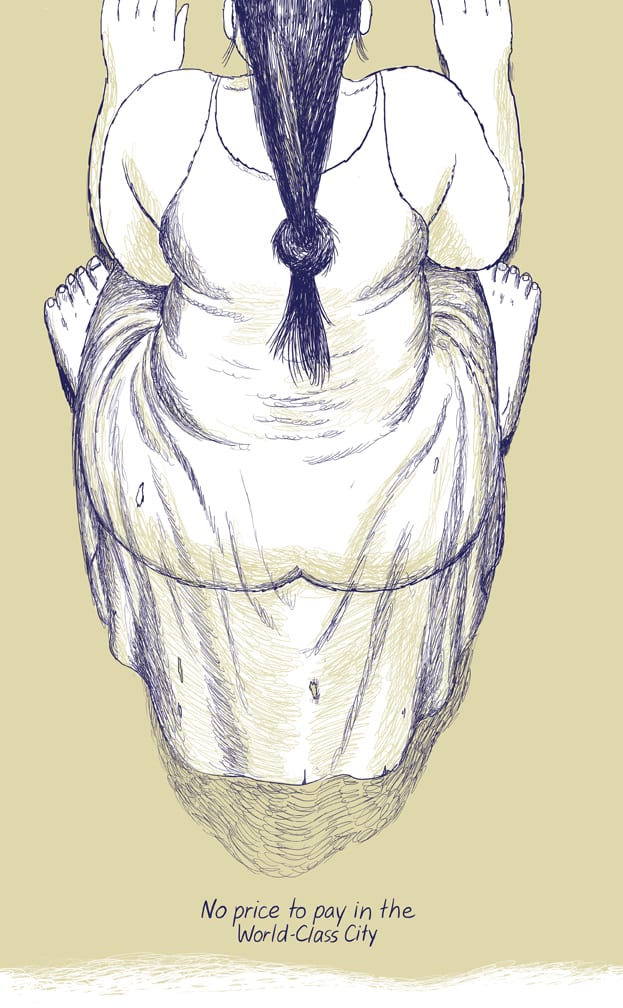

Playing with shot-reverse-shots and perspective-altering reveals with every page-flip, Tamaki forces the reader to re-consider each connection between a story's images and words. Oftentimes, Tamaki’s rough-hewn, partitioned, silhouetted, or highly-contrasted bodies present themselves as opportune vehicles for the reader’s own bodily experience. Sometimes Tamaki renders bodies highly materially: carefully detailing variations in each facial contour, wrinkle, and mark that captures a person’s unique identity. Other times, the lines are sparse, a few broad strokes on an empty page. The latter style invites the universal experience into the represented body while subverting the body’s materiality. Even through the gaps of such incongruous character renditions, Tamaki demonstrates the webs and gaps, the boundaries of representation, and the effects perception can have on our constructed social realities.

Playing with shot-reverse-shots and perspective-altering reveals with every page-flip, Tamaki forces the reader to re-consider each connection between a story's images and words. Oftentimes, Tamaki’s rough-hewn, partitioned, silhouetted, or highly-contrasted bodies present themselves as opportune vehicles for the reader’s own bodily experience. Sometimes Tamaki renders bodies highly materially: carefully detailing variations in each facial contour, wrinkle, and mark that captures a person’s unique identity. Other times, the lines are sparse, a few broad strokes on an empty page. The latter style invites the universal experience into the represented body while subverting the body’s materiality. Even through the gaps of such incongruous character renditions, Tamaki demonstrates the webs and gaps, the boundaries of representation, and the effects perception can have on our constructed social realities.

Tamaki’s chapters, “Body Pods” and “1.Jenny” visualize, represent, examine, and question how invisible social constructions affect perceptions of ourselves and our realities: What is natural and what is artificial? What is fact and what is fiction? Who are we and how do others shape who we are? Perhaps ultimately, what is the meaning of life and death? In Boundless, the fictive and the real casually coincide in a characters’ existence and in Tamaki’s composition. While the narrator of “Body Pods” reflects on a celebrity death, her boyfriend, Alex, suddenly announces he’s been cheating. The unexpected drama and unreality of the situation is at once gutturally human and artificially staged. As the narrator storms away from Alex, she runs deeper into the woods, perturbed by Alex’s disengagement with the artificial social script of her expectations: “He didn’t cry or fight back or try to make me stay, which was extremely irritating.” Requiring the natural to be more artificial is ironized by her position in the lush forest setting. As Alex’s voice echoes in her recollection, “We’re all going to die one day,” the narrator clings to the artificial to suppress the naturalism of death, be it relational or bodily – the only coping mechanism she can employ.

In another chapter, “1.Jenny,” the question of the Mirror Facebook, is the question of “What is reality?” or “What space constitutes reality?” As Jenny falls further into the internet space occupied by her alternate-self, Tamaki’s metaphoric inclusion of other natural-yet-artificial spaces are also explored. Jenny dives into water, swimming in circles in the liminal space of an artificial water receptacle – a public pool. Similarly, Jenny is socially swimming in circles, immersed in a fluid medium that feels like its natural counterpart: an interconnected social life in an artificial, enclosed space – the internet. As Jenny’s therapist observes of her obsession with the Mirror Facebook: “Whether it’s ‘real’ or not is irrelevant. The value of the profile is the response it provokes within you.” With such compelling sequences Tamaki asks: What might it be like to look upon yourself from the outside? To consider your opposite self? To consider natural and artificial boundaries? What response does the medium provoke within you? While Tamaki creates the text to question, probe, and circle, her interactive and innovative compositional approach ultimately leaves the answers up to the reader.