Four or five generations have now passed since the hugely admired drawings of Art Young appeared in the “slicks” of the 1910s-30s, not to mention his central role in The Masses (1913-17), the magazine of Greenwich Village’s radical bohemians. He had not been entirely forgotten before the important collection To Laugh That We May Not Weep: The Life and Times of Art Young, offered readers a sense of Young’s full range.* The volume under review here explores the singular subject that occupied the artist’s attention throughout his artistic life.

Young’s mixture of melancholy and sharp humor finds many a soulmate today amid a myriad of artists struggling to reflect upon the down side of a civilized “progress” laden with poverty, wars and environmental destruction. None of these has Young’s unique touch.

He drew three versions of Hell and surely, in his mind, never left the matter behind. No doubt we can trace a large element of his discontent to his small town boyhood (in Monroe, Wisconsin) where a copy of Gustave Dore's drawings made a life-long impression. Young’s early work as an illustrator for the Chicago daily papers no doubt encouraged his instinct to contrast the claims of the burgeoning prosperity—civic improvements of all kinds—against the ambience of the world that had he left behind. Noise, industrial and urban smells, rude crowds, and the haughty, rising middle class so desperate to emulate the wealthy assaulted his senses and only got worse with his subsequent move to New York. Seen differently, he had actually prepared himself early, already making fun of small town social foibles. The wide world offered better targets.

The story of Young’s conversion to socialism near the turn of the twentieth century is by now familiar, while his role as an affable senior figure of at the Masses, working amidst the most brilliant outpouring of magazine art heretofore in the US, is only a little less familiar. The Fantagraphics selection of his work made abundantly clear how seriously he took his formal training in art.

The story of Young’s conversion to socialism near the turn of the twentieth century is by now familiar, while his role as an affable senior figure of at the Masses, working amidst the most brilliant outpouring of magazine art heretofore in the US, is only a little less familiar. The Fantagraphics selection of his work made abundantly clear how seriously he took his formal training in art.

Art Young’s Inferno, long out of print, may be viewed as a summing up of his talents. Nowhere in its pages do we find the word “socialism,” although the book appeared originally in 1933, the depth of the Depression and arguably, the apex of radical rhetoric until at least the later 1960s. He had, perhaps, seen too much already for any wild utopian leap of faith. Or perhaps the dreamy view of a better future, most especially of Red Russia, had never quite persuaded him.

Art Spiegelman explains, in the introduction of To Laugh That We May Not Weep, what we need to know about Young’s artistic approach. Advancing from his early interest in Dore and Thomas Nast, Young grew into his “signature, mature style of streamlined ink lines echoing early twentieth century modern woodcuts,” leading to the “boldly composed later line work that fully embodies the paradox of humble virtuosity.”

Spiegelman calls Young’s accomplishment the genius work of a master who managed to find and rework images coherent both intellectually and formally, as art, and to explain through their use the reality of class struggle. Art Young’s Inferno, the artistic statement of a radical artist in late middle age, comes a little closer to being a curse upon a doomed civilization.

Spiegelman calls Young’s accomplishment the genius work of a master who managed to find and rework images coherent both intellectually and formally, as art, and to explain through their use the reality of class struggle. Art Young’s Inferno, the artistic statement of a radical artist in late middle age, comes a little closer to being a curse upon a doomed civilization.

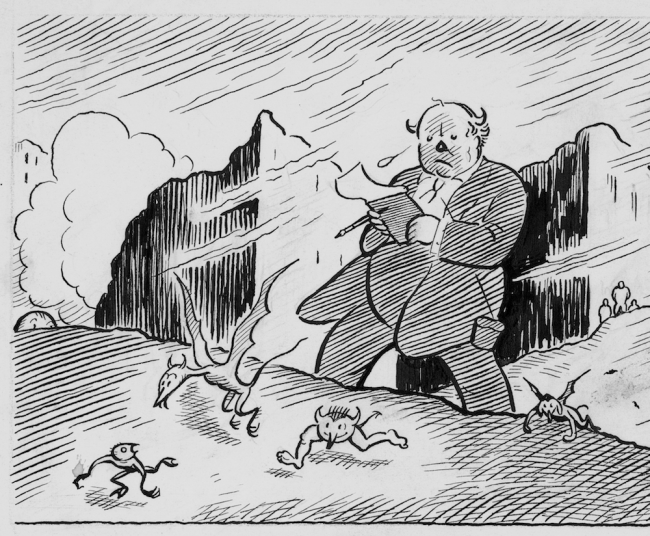

His judgment necessarily echoes Dante and the feeling that something important has eluded the best minds for centuries. A particularly famous Art Young cartoon, more radical even than the socialist publications where it appeared, shows a lion encaged, dreaming of jungle freedom. Something lost, not to be regained. Satire is a form of mourning. But it is mourning, also, in an astonishing lighter vein: Young’s masterpiece is howlingly funny. The Inferno’s residents are, for instance, without clothes, true to some of Dante’s own famous illustrators including Dore, but in these pages delightfully vulnerable, the plump American middle classes of the 1920s, with starvelings here and there. Taken by themselves, they would be as funny as New Yorker drawings even sans captions.

For the artist’s final visit to the Underworld—a journalist’s six-week tour—Young has invented a brilliant narrative in which Satan, once all powerful, has been reduced to a mere functionary or less than that, in what amounts to a grand modern, urbanized civilization below earth’s surface. How did it happen? Capitalists sent downward for their sins re-create an earthly capitalism, made worse by the reigning hypocrisy. Modernization has replaced “Abandon Hope, All You Who Enter Here,” with a giant “Welcome to Hell” sign. The noxious mixture of sulphur and combustion engine smoke in the air is neatly offset by sprays of perfume: the initiating metaphor.

For the artist’s final visit to the Underworld—a journalist’s six-week tour—Young has invented a brilliant narrative in which Satan, once all powerful, has been reduced to a mere functionary or less than that, in what amounts to a grand modern, urbanized civilization below earth’s surface. How did it happen? Capitalists sent downward for their sins re-create an earthly capitalism, made worse by the reigning hypocrisy. Modernization has replaced “Abandon Hope, All You Who Enter Here,” with a giant “Welcome to Hell” sign. The noxious mixture of sulphur and combustion engine smoke in the air is neatly offset by sprays of perfume: the initiating metaphor.

The bankers and capitalists, cursed for their earthly sins, still suffer, of course, but not much. The real suffering is experienced by Hades’ poor. But these poor proles and sub-proles never revolt. They crave to enjoy the new consumer culture they hear about on the radio—from advertisers of course—and relish the violence of sports, the glory of military parades, and so on. They can keep fit by crushing their bodies against each other on the subway and keep up to date by admiring—from the outside— the hellion bands playing accursedly loud music in the better venues.

This version of hell sometimes even overwhelms the sensibilities of the blindly aspiring (meanwhile, perspiring) middle classes. They cheerfully accept all manner of public graft and gangsterism, while a chorus of public “cheerupists” eternally urges optimism, promising that times will always get better. If capitalism on the surface is doomed to self-destruct—as Young seems to suggest—then Hades is the true salvation.

This version of hell sometimes even overwhelms the sensibilities of the blindly aspiring (meanwhile, perspiring) middle classes. They cheerfully accept all manner of public graft and gangsterism, while a chorus of public “cheerupists” eternally urges optimism, promising that times will always get better. If capitalism on the surface is doomed to self-destruct—as Young seems to suggest—then Hades is the true salvation.

The narrative might grow repetitious except for Young’s laconic quips and marvelous drawing. Page after page of inventive combinations of every baneful “modernizing” influence that he experienced across his long life find their way here. Although dead, the inhabitants must still insure themselves. Even humor is corrupted from social commentary to banal comic relief and “the patter of whatthehell sophisticates.”

As Art Young’s Inferno closes, a demoralized Satan complains to the traveler that he once had a unique zone of punishment all to himself. “Then they went to work and made a competing Hell on Earth. Civilization, you call it…Not satisfied with making the upper world a Hell for everybody including themselves, these brains of business came down here and—forced—me—out.”

As Art Young’s Inferno closes, a demoralized Satan complains to the traveler that he once had a unique zone of punishment all to himself. “Then they went to work and made a competing Hell on Earth. Civilization, you call it…Not satisfied with making the upper world a Hell for everybody including themselves, these brains of business came down here and—forced—me—out.”

Art Young, where are you now, when we need you most? Not in Hades, we trust.##

* To Laugh That We May Not Weep, edited by Glen Bray and Frank M. Young (with an introduction by Art Spiegelman and comments by others including Justin Green). Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2017.